This article has been peer-reviewed under the direction of Professors Mary Elizabeth Leighton and Lisa Surridge (University of Victoria). It forms part of the Great Expectations Pregnancy Project, funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Margaret Waters, from The Illustrated Police News 331 (15 Oct. 1870): cover image (detail).

In 1803, a significant change occurred in the law governing infanticide. An unprecedentedly harsh criminal statute, enacted in 1623 against unmarried mothers accused of killing their children, was modified to be less harsh. However, moral judgments of unmarried women who gave birth to illegitimate children, known as "bastards" under the law, remained influential in the discourses and practices of law, medicine, and journalism throughout the Victorian era. The nineteenth century is also notable, however, for the crescendo of voices that sought to shift the conversation around infanticide to address issues of poverty, the sexual double standard, bodily integrity, access to birth control, and women’s inequality in both the public and private spheres.

The case of Sarah Hawkins, a young, unmarried servant woman from Bristol who gave birth to a stillborn child in 1708, offers insights into the law before—but also after—the turn of the nineteenth century. While the stories of the lives and circumstances of most servant women remain unknown, Hawkins is not lost to history. Instead, you can find reference to her in the British Library’s index as "Sarah Hawkins, infanticide." Legal documents detail part of her story because an appeal was made "To the Queens [sic] Most Excellent Majesty" on her behalf. She had been convicted of the murder of her illegitimate child and sentenced to death. The legal documents state that she had been seduced by a man who then did not show up at her trial to testify that she had made preparations for the child’s birth. His absence left her open to being convicted under the governing law of infanticide at the time, a 1623 statute providing that an unmarried woman who had concealed the birth of a child that subsequently died was presumed guilty of killing that child. Unlike in any other statutes in Anglo-American law, in these particular circumstances the presumption of innocence was reversed—a woman who concealed an illegitimate pregnancy and whose child died was assumed to be guilty of infanticide, unless proven innocent.

Hawkins’s appeal to the queen was successful: the queen ordered a new trial at which Hawkins’s employer testified that she had fallen down the stairs the week before giving birth, the accidental fall likely causing the stillbirth. Her employer also testified that there was no evidence of violence toward the child. In some ways, Hawkins was lucky. After being convicted under the harsh statute, Hawkins was partially pardoned for the death: she was transported rather than hanged. Someone invested in this servant’s defense and appeal; as well, her employer and lawyers—people with more authority and power to speak than she—told her side of the story.

But is this a tale of justice? Of mercy? The court believed that the baby was stillborn, that it had died through no fault of Hawkins, and that she had been deserted by the man who did know of her pregnancy—and thus that she had not concealed it. So, why was she transported? Of what was she guilty? While this case could be characterized as one of leniency, the fact is that this unmarried woman was sent away from what was viewed as "good" society, apparently punished for the crime of her inappropriate sexuality. The law continued to police this threat of uncontained female sexuality throughout the nineteenth century, even with the 1803 legal changes. Lesser punishments were available, but it was solely in the hands of the law whether or not mercy was shown—that is, whether the woman was or was not too much of a disruption to deeply entrenched cultural ideas about acceptable womanhood.

Infanticide and the Law

Enacted in 1623, this first English statute to address infanticide read as follows:

[I]f any woman . . . be delivered of any issue of her body, male or female, which being born alive, should by the laws of this realm be a bastard, and that she endeavor privately, either by drowning or secret burying thereof, or any other way, either by herself or the procuring of others, so to conceal the death thereof, as that it may not come to light, whether it were born alive or not, but be concealed: in every such case the said mother so offending shall suffer death as in case of murther, except such mother make proof by one witness at the least, that the child (whose death was by her so intended to be concealed) was born dead. [21 James I, c. 27.]

[The text of the statute referenced in this article is from Pickering, Statutes at Large 298; I refer to this statute as the 1623 statute because that is the date cited in this source. In the Statutes of the Realm, the date is cited as 1623-4.]

The statute applied only to "lewd women that have been delivered of bastard children, [who] to avoid their shame, and to escape punishment, do secretly bury or conceal the death of their children" (21 James I, c. 27). It thereby shifted the burden of proof so that an unmarried mother accused of infanticide was presumed guilty unless she could produce a witness to swear that her child had been born dead. While any man (including the father) or any woman (except the mother) accused of killing a child would be tried for murder and presumed innocent unless proven guilty, the "lewd" mother of a "bastard," if she attempted to conceal its birth and death, was guilty under the statute regardless of how the child died. If a woman delivered a stillborn child alone, for example, she would be guilty of murder under the statute because she would be unable to produce any witnesses.

The 1623 statute was enacted out of concern that so-called "lewd women" were escaping the bastardy clauses of the 1576 "poor law" (18 Eliz. I, c. 3), which mandated that an unmarried pregnant woman declare the name of her unborn child’s father so that the parish could collect support from him. This law also mandated corporal punishment and jail time for both parents. Women, however, bore the brunt of this social control, with fathers either fleeing or disputing paternity claims (Hoffer 13-17). With the high rate of infant mortality (see Marland), the bastardy laws provided considerable incentive for an unwed mother to conceal her pregnancy. In the not-unlikely event that her child was stillborn or died from other natural causes, she might, through concealment, be able to escape punishment under the bastardy laws, as well as the social judgment that the law abetted and legitimized. The 1623 statute greatly raised the stakes of concealing illegitimate pregnancies: if discovered to have concealed a pregnancy that resulted in a dead child, the woman was presumed guilty of a capital offense. Hoffer and Hull report a fourfold increase in the prosecution of infanticide cases after the passage of the 1623 statute (27), as well as a growing association between illegitimate pregnancy and infanticide (23).

In 1803, the 1623 statute was repealed and replaced by Lord Ellenborough’s Act (43 Geo. III, c. 58), which treated infanticide like other cases of murder, with no presumption of guilt. As unmarried mothers were still the only parties referenced in the 1803 law, it does not reflect a change in the legal or moral judgment of so-called "fallen women." Rather, the 1623 law, as written, was not working. While the statute had resulted in a rise in the prosecution of infanticide cases, in the eighteenth century, there was a sharp decline in the number of convictions, with both judges and juries loathe to sentence accused women to death. Although the law did not require proof that the child had been born alive, it became judicial custom to demand such proof. Live birth was difficult to prove, especially because judges became increasingly less likely to rule that the floating of the infant’s lungs (to show that they contained air) was conclusive evidence that it had been born alive. Also, juries were open to accepting a wide array of defenses. A woman could invoke the so-called benefit-of-linen defense if, by producing baby clothes she had sewn before the birth, she could show that she had not been trying to conceal a birth and had been looking forward to motherhood. Accused women were often acquitted based on the want-of-help defense, arguing their inability to keep the infant from falling onto a rough floor, into a bucket, or into a privy. Under this defense, mothers also could argue that they had been unable to tie off umbilical cords or had missed when doing so and inflicted mortal wounds because they lacked skill or self-possession or were medically incapacitated. Temporary insanity was also a common defense.

The new 1803 law provided that if the mother of "a bastard child" were acquitted of its murder, she could, instead, be found guilty of concealment of birth and sentenced to up to two years in prison. In other words, she could be convicted of a crime with which she had never been charged. In 1828, concealment of birth became its own distinct offense, and the law was changed so that any woman, not just an unmarried woman, could be charged under the statute (Offenses Against the Person Act of 1828, 9 Geo. IV, c. 31). The crime of concealment of birth was further broadened in 1861 so that any person could be charged with the crime.

In the mid to late nineteenth century, other laws singling out infanticide were proposed to address the cultural moral panic over infanticide that reached fever-pitch in the 1860s. Medical men such as Dr. William Burke Ryan sounded the alarm that "the feeble wail of murdered childhood in its agony assails our ears at every turn, and is borne on every breeze. . . . [W]e try to turn away the gaze . . . [b]ut turn where we may, still are we met by the evidence of a wide spread crime" (45-46). As Anne-Marie Kilday explains, the introduction of the coroner’s office further contributed to the sensationalism around infanticide. Many coroners felt the need to demonstrate their societal value and justify their fees:

[S]ome did this by overstating the size of their workload, by providing flawed and inflated statistics regarding local, regional and national fatalities and by instigating zealous crusades about issues that related to their official concerns. Consequently, by routinely raising their disquiet about the increasing incidence of infanticide in the press, citing inaccurate data, and employing colourful, hyperbolic language, coroners made a significant contribution to the moral panic. [Kilday 121]

National attention to this issue increased as "fears of mass infanticide provided grist for the mills of an expanding press" (Behlmer 406), especially as daily newspapers became cheaper and increased their circulation. These stories had the potential to further entrench stereotypes about class and gender, as well as reinscribe cultural ideas about morality. Describing the considerable attention that the Daily Telegraph, the Daily News, and the Standard gave "to stories of infants retrieved from cesspools and privies," G.K. Behlmer notes that "[r]espectable readers may have greeted such gruesome news as confirmation of the innate moral depravity of the lower classes" (407). Also, drawing on centuries-old censure, the reported crisis featured murderous mothers:

It is . . . exceedingly unpleasant to find ourselves stigmatized in foreign newspapers . . . . as "a nation of infanticides;" . . . . The Papal Government even went so far as to send over an emissary, the Abbé Césare Contini, to collect statistics; and his report . . . gives the astounding . . . intelligence that 13,000 children are yearly murdered by their mothers in heretical England. [my emphasis; "Occasional Notes," 9]

Clearly, the conflation of infanticide, gender, and morality was automatic and unquestioned.

Another contributing factor to the Victorian obsession with infanticide in the 1860s and 70s was the famous baby farmer cases, including that of Mrs. Waters in the 1870s. Waters was convicted of murdering one child and suspected of being responsible for the deaths of some forty others. These cases demonized not only those who ran these establishments, but also those who made use of them–the familiar character in infanticide discourse, the unmarried working-class mother. This cultural uproar led to many calls for the law to intervene, and legal proposals were made, for example, to stiffen the penalties for concealment of birth and to regulate childcare more stringently. Changes to the bastardy laws or other legal reforms that would have ameliorated the disastrous economic circumstances in which most of the accused women found themselves were not on the table. Ginger Frost has highlighted the hypocrisy in the legal response to infanticide. Accused unmarried mothers were often acquitted of murder or concealment charges or received light penalties because judges felt sympathy for their plight or indignation towards irresponsible seducers; however, "this anger was unaccompanied by any acknowledgment of the way the law enabled—or even encouraged—such behaviours" (Frost 70).

The Committee to Amend the Law in Points Wherein It Is Injurious to Women (CALPIW), formed by Elizabeth Wolstenholme, Josephine Butler, and Lydia Becker in 1871 in response to "reform" efforts, called out this hypocritical stance. In a pamphlet entitled "Infant Mortality: Its Causes and Remedies," CALPIW offered a well-documented, compelling critique of proposals that had been suggested to curb the incidence of infanticide. The committee expressed its conviction that "direct infanticide has little to do with the terribly high death-rate prevailing among young children" (24) and accused lawmakers of diverting attention away from the real causes of infant mortality: low wages for women, seduction, lack of education, a wife’s conjugal duties, male sexual and financial irresponsibility, the difficulty of unmarried mothers in finding work, and unjust laws resulting from "the natural inclination to regard every question from an exclusively masculine point of view" (24).

Feminists also highlighted similarities between medical and legal discourses on the topics of infanticide and the Contagious Diseases Acts (see Hanley), both grounded in "the double standard of sexual morality" and "attitudes which condemned women having premarital sex but largely ignored men who did so" (Grey 405). From 1871 to 1881, CALPIW and then the Vigilance Association for the Defence of Personal Rights (VADPR) supported lawsuits brought by women who had been subjected to forced gynecological examinations in connection with infanticide investigations. While this critique of legal and medical responses to infanticide was integrally linked to other late-century campaigns "to restore and maintain the integrity of the female body against punitive medico-legal surveillance and control," an 1881 legal defeat derailed this line of argumentation for more than thirty years (Grey 415-16).

CALPIW also condemned proposals involving compulsory registration, licensing, and supervision of all infant caretakers (including daycare providers), arguing that they interfered with women’s employment opportunities and involved inappropriate surveillance, "increasing officialism, police interference, and espionage" (7). Despite these efforts, the Infant Life Protection Act passed in 1872, imposing rules and registration requirements for a broad spectrum of childcare providers.

No other laws specific to infanticide were passed in England until the 1922 Infanticide Act (Geo. V, c. 18). Illegitimacy, however, continued to bring "financial disaster" upon unmarried mothers and shame from which there was no escape (Frost 49). As Ann Higginbotham concludes,

The Victorians could grapple with the problem of crime. Solving all the problems of illegitimacy, however, would require rethinking fundamental assumptions. . . . To change the conditions of unmarried mothers would also have meant abandoning what seemed to many Victorians an axiom of public morality: to aid the immoral would simply encourage vice. Throughout the nineteenth century, infant deaths were more readily tolerated than easy virtue" [337].

CALPIW and VADPR exposed that, under the moral cover of protecting infant life, the law’s response to fears of infanticide was also responsible for keeping important issues off the table and controlling women’s options, opportunities, and bodies. In such ways, the law (even when choosing to show leniency in individual cases) colluded with other authoritative discourses to control women, the boundaries of public morality, and the cultural meanings of infanticide.

Cultural Ideas about Infanticide

Under no possible system of police, however elaborate, could all working mothers in England be watched in order to make certain that they should not murder their own children. We could, perhaps, prevent their eating them, or burying them secretly for children can be counted; but their killing them is not preventable. . . . There is, in fact, no defence for young children, and can be none except the mother’s feeling for them; and when that is absent, or has been changed into abhorrence, they must, as far as society can help it, just die at their mothers’ discretion. The only cure worth anything is a change in the women’s hearts ["Judges’ Opinion" 44].

There was much interplay between the legal treatment of infanticide and cultural gender rules and roles in the Victorian period. Studies confirm that the law tended to judge the woman rather than the crime: "[d]escriptions of women’s crime frequently referred to past conduct, marital status, protestations of regret, or shamelessness, and even to the woman’s physical appearance" (Zedner 30). Women’s crimes were often explained in terms of natural feminine traits gone awry: "the perceptions that violent women acted from individual rather than environmentally produced motives and that there was something wrong with them as women if they chose aggression rather than acquiescence run as constant themes through the journal articles, charges to juries, and crime histories of the century" (Morris 27). Specifically with respect to infanticide prosecutions, the "more unconventional the woman’s behavior and background, the more likely she was to lose the sympathy of the court" (Higginbotham 333). Moreover, Higginbotham reports that, regardless of actual conviction rates, many Victorians were all too ready to suspect unmarried women of murdering their infants, to make the connection between "lewd women" and infanticide.

In the many cases where women pled guilty to concealment of birth, the legal defense of insanity did not come into play. It was also not often argued when the accused’s defense was that the child had been stillborn or the death accidental. But when lesser charges were not available, or the facts were particularly damning, temporary insanity was a common defense. This explanation made sense of acts that violated cultural understandings of women’s innate maternal instincts and nurturing nature, while also drawing upon and reinscribing beliefs about women’s biology and mental frailty. In the 1830s, James Pritchard introduced the term "moral insanity" to describe deviant behavior that could account not only for a woman’s infanticidal act but also for the excessive sexuality that might have led to her "fall" in the first place (4-5). Correspondingly, the female body, especially after childbirth, was viewed as being susceptible to madness and moral perversion. While a defense of temporary insanity may have saved certain women from being held accountable for their actions, such a defense reinforced stereotypes associating women with mental weakness.

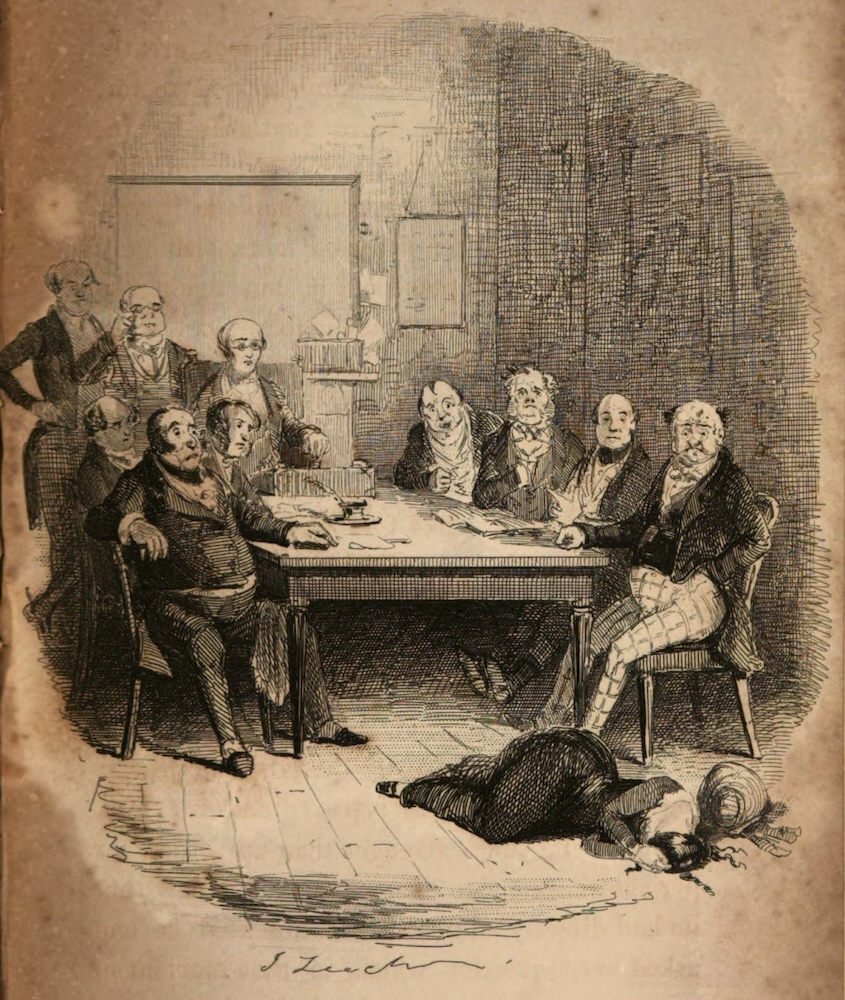

"Jessie Before the Board," from Jessie Phillips: A Tale of the Present DayVol. II, facing p. 186. London: Henry Colburn, 1843.

While feminist activists such as those who formed CALPIW fought against legislation that blamed and punished individual women for societal problems, interfered with women’s employment opportunities, and overly regulated childcare, other feminists were changing the discourse around infanticide in other ways. Although George Eliot’s Adam Bede (1859), which includes Hetty Sorrel’s trial for infanticide, reinforced social assumptions about sexuality, deviance, and crime, other lesser-known novels interrogated those associations (Kalsem 33-67). Frances Trollope’s Jessie Phillips: A Tale of the Present Day (1843) told a different story about infanticide. Published in the wake of the 1834 New Poor Law, which made an unmarried mother solely responsible for the maintenance of her child, Trollope’s novel about a single working-class woman who is falsely accused of infanticide illuminates the economic crisis in which such women found themselves. Because of her pregnancy, Jessie loses all prospects of supporting herself and her child in "respectable" employment, and the novel depicts workhouse life in graphic detail. Moreover, it highlights the injustices of the law’s assumptions about infanticidal women and illustrates the connections between the law’s regulation of "deviant" women and its institutional control over all women. Not surprisingly, Trollope was chastised for writing about such topics at all, let alone in such a way:

The particular clause of the Act which [Mrs. Trollope] has selected for reprobation is the bastardy clause—not perhaps the very best subject for a female pen. And then, in order to give dramatic effect to this subject, we have the seduction of Jessie Phillips, her pregnancy, the birth of the child, and its supposed murder by the guilty mother, discussed by two young ladies (Ellen Dalton and Martha Maxwell), of which discussion, the discovery of the body, the probabilities of Jessie being in a condition, just after parturition, to be able to destroy the child, and the enormity of the crime, are the prominent points. We admit that Mrs. Trollope manages these details with as much delicacy and reserve as their nature would admit of, but they are essentially unfit materials. They are, of necessity, suggestive of circumstances which are always repulsive in their character, and peculiarly so when made the subject of lengthened conversation between two young, artless, and inexperienced girls. [Review of Jessie Phillips, 732]

Nineteenth-century women kept writing about infanticide anyway. Two other novels that feature central characters who are falsely accused of infanticide are Caroline Leakey’s The Broad Arrow (1859) and Mary Tuttiet’s The Last Sentence (1891). Additionally, Elizabeth Barrett Browning "chose to incorporate the act of infanticide into ‘The Runaway Slave’ and allusions to infanticide into Aurora Leigh" to link these poetic texts "with many other works by social reformers . . . who used infanticide as a symbol of the catastrophic failure of various social systems" (Ficke 250). Specifically, "infanticide narratives did provide compelling illustrations of the hypocrisy of social and legal systems that insisted . . . that women were formed to nurture children, and yet set up numerous restrictions and barriers that prevented women from being able to do just that" (Ficke 250). Male writers also presented feminist perspectives on infanticide, with George Moore’s Esther Waters (1894) centering on the plight of an unmarried mother in the context of a baby-farming scenario. These novels resisted authoritative and influential voices such as the above "Judges’ Opinion on Child-Murder." These "outlaw texts" (Kalsem 5) showed that no change in the mother’s heart was necessary; instead, society needed a shift to acknowledge and remedy the desperate situation in which mothers found themselves, with children to support and not enough money to pay for food and care.

In her study of child murder as a motif, Josephine McDonagh analyzes infanticide as "accreting layers of meaning that are intricately related to the contexts in which they appear" (8). She describes child murder in the 1890s as embedded in topics of the day such as birth control, eugenics, and the controversial "New Woman." Such women were "associated with promoting social legislation aimed at broadening female independence . . . involved in campaigning on such issues as divorce, married women’s property, the custody of children, the education of girls, rights for women to pursue careers in the professions, and latterly, votes for women—causes that would impact on the nature of the traditional family" (McDonagh 157). Similarly, in her analysis of press coverage of infanticide from 1822 to 1922, Nicola Goc concludes that "sensationalized infanticide discourses not only entertained the masses but also educated society on the deviancy of young unmarried women, compounding anxieties about the ‘women question’ and the changing role of women in an increasingly industrialized and urbanized society" (2).

Given these cultural contexts, it is unsurprising to see the slippage in this late-century legal view on infanticide, "the Judges’ Opinion," from a disapprobation of unmarried mothers to "all working mothers in England" (44).

Links to Related Material

Bibliography

Act to Prevent the Destroying and Murthering of Bastard Children, 21 Ja.1, 1623, c. 27. The Statutes at Large Vol. 7, ed. Danby Pickering, 298. Cambridge: 1763.

Behlmer, George K. "Deadly Motherhood: Infanticide and Medical Opinion in Mid-Victorian England." Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 34(4) (1979): 403-27.

"Committee For Amending the Law in Points Wherein It Is Injurious to Women." Infant Mortality: Its Causes and Remedies. Manchester: Ireland, 1871.

Ficke, Sarah H. "Crafting Social Criticism: Infanticide in ‘The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point’ and Aurora Leigh." Victorian Poetry 51(2) (2013): 249-67.

Frost, Ginger S. Illegitimacy in English Law and Society, 1860-1930. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2016.

Grey, Daniel J.R. "‘What Woman Is Safe . . .?’: Coerced Medical Examinations, Suspected Infanticide, and the Response of the Women’s Movement in Britain, 1871-1881." Women’s History Review 22:3 (2013):401-21.

Goc, Nicola. Women, Infanticide and the Press, 1822-1922: News Narratives in England and Australia. Farnham: Ashgate, 2013.

Higginbotham, Ann R. "‘Sin of the Age’: Infanticide and Illegitimacy in Victorian London." Victorian Studies 32 (1989): 319-37.

Hoffer, Peter C., and N. E. H. Hull. Murdering Mothers: Infanticide in England and New England 1558-1803. New York: New York UP, 1981.

Infant Life Protection Act, 37 & 38 Vict., 1872, c. 38.

Infanticide Act, 12 & 13 Geo. V, c. 18.

"The Judges’ Opinion Upon Child Murder." Spectator (12 July 1890):44.

Kalsem, Kristin. In Contempt: Nineteenth-Century Women, Law, and Literature. Columbus: Ohio State UP, 2012.

Kilday, Anne-Marie. A History of Infanticide in Britain c. 1600 to the Present. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Lord Ellenborough’s Act.43 Geo. III, 1803, c. 58.

McDonagh, Josephine. Child Murder and British Culture 1720-1900. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2003.

Morris, Virginia. Double Jeopardy: Women Who Kill in Victorian Fiction. Lexington: UP of Kentucky, 1990.

"Occasional Notes." Pall Mall Gazette (30 April 1866): 9.

Offenses Against the Person Act, 9 Geo. IV, 1828, c. 31.

Poor Law, 18 Eliz. 1, 1576, c. 3.

Prichard, James C. A Treatise on Insanity. London, 1835.

Review of Jessie Phillips: A Tale of the Present Day. John Bull 18 Nov. 1843: 732.

Ryan, Wiliam Burke. Infanticide: Its Law, Prevalence, and History. London, 1862.

"To the Queens [sic] Most Excellent Majesty." Prisons: Petitions to Qu. Anne, George I, etc., of and Rel. to Detained Criminals: 1706-1719. British Library. Add MS 61618.

Zedner, Lucia. Women, Crime, and Custody in Victorian England. Oxford: Clarendon, 1991.

Created 3 February 2024