[All photographs are from the book under review. Click on images to enlarge them. — George P. Landow]

There are significant and original creative figures in every era that, for various reason, are overlooked or neglected by future generations. The American sculptor Moses Jacob Ezekiel is undoubtedly one such figure. In his time—his life spanned from 1844-1917—Ezekiel was widely admired as an artist, honored by knighthoods from several European courts, and befriended by artists and thinkers such as Franz Liszt, Richard Wagner, Mark Twain, Emile Zola, and Sarah Bernhardt. His unusual home in the Diocletian Baths of Rome contributed to his reputation as a brilliant if eccentric artist. Yet today Ezekiel is largely forgotten, despite his major contributions to nineteenth-century art. Ezekiel’s life also featured involvement in various extraordinary events: for example he fought on the Confederate side of the American Civil War, present at the famous battle at Shenandoah Valley. He was a witness to major political shifts of political power: his arrival in Rome coincided with the anniversary of the downfall of papal temporal power, allowing him to witness the transformation from papal to Republican Rome. As a Jew, Ezekiel encountered anti-Semitic prejudice both as a student at Virginia Military Institute—where he was the only Jewish cadet—and in his later artistic career. Peter Adam Nash—himself a descendant of Ezekiel—is the ideal biographer for this complex, eclectic and fascinating figure. Nash’s involvement in his subject’s life is apparent throughout these pages, yet he remains detached and critical. For example, Nash shows how Ezekiel’s refusal to raise funds by producing factory-like replicas—as some of his contemporaries did—seriously impeded his ability at times to exhibit his work. In one case, his sculpture was only erected after the exhibition it was intended for—the American Centennial Celebrations—had closed.

Left: Ezekiel’s studio in the ancient Baths of Diocletian. (Courtesy of the Jacob Rader Marcus Center of the AmericanJewish Archives, Cincinnati, Ohio. Right: Religious Liberty. (National Museum of American Jewish History, Jeff Goldberg/Esto)

Nash does an excellent job not only of conveying the intricacies of Ezekiel’s multi-faceted life, but also of evoking the atmosphere of late-nineteenth century European culture. For example, Nash notes that Ezekiel and his friends in Rome “would have eaten at Coradetti’s and in the smoke-darkened rooms of Caffé Greco, both popular haunts of esteemed and aspiring artists. And they would have seen some shows: an opera at the Argentina, the famous marionettes at the Rossini, perhaps enjoyed the weekly chamber music at the Constanzi or the Nazionale”(77). Nash combines the scholar’s meticulous research with the novelist’s eye for detail and narrative flair, resulting in a book that evokes the fin-de-siècle in all its decadent opulence. The book’s early chapters on Ezekiel’s Spanish roots effectively establish the Iberian background of this complex and often misunderstood American artist. Ezekiel was unique in combining European and American influences in his work and moving between nations and cultures with ease, despite a rampant anti-Semitism in Europe. Ezekiel, a homosexual, was also subject to the homophobic prejudice that brought about the downfall of contemporaries such as Oscar Wilde.

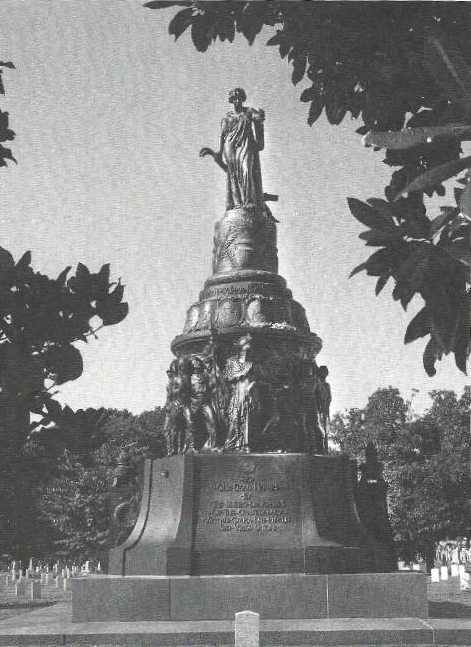

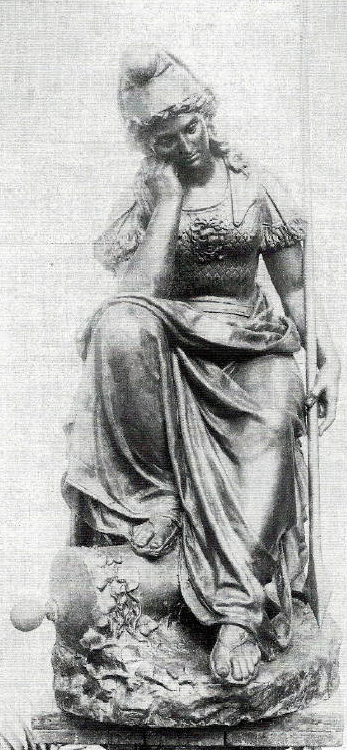

Left: The New South. Confederate Monument,Arlington National Cemetery, Washington, D.C. (Courtesy Keith Gibson) Right: Virginia Mourning her Dead. (Courtesy of the Virginia Military Institute Archives. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

One of Nash’s most compelling chapters treats of two late nineteenth-century scandals, the trials of Captain Alfred Dreyfus for treason in 1894, and the trials of Oscar Wilde for “gross indecency” in 1895. While noting that Ezekiel omitted any mention of either scandal from his “otherwise garrulous memoirs”(117), Nash leaves no doubt in the reader’s mind as to the personal significance of these crises for Ezekiel’s identity. Both Wilde and Dreyfus were prominent victims of popular prejudice. If Dreyfus as a Jewish officer “proved the perfect foil for the…beleaguered nation, a scapegoat for all of France’s ills” (117), then the same could be said for the homosexual Wilde in crisis-ridden Victorian England. At a time when the British class system was being revolutionized by democratic reform and calls for sexual equality, Wilde’s attempt to bring down a British aristocrat—the Marquis of Queensberry—placed him beyond the pale. Nash sets the scene of these scandals powerfully, noting that Ezekiel in Rome, “as a Jew, a military man, and a homosexual—must have been especially attuned to these sensational trials…His sense of vulnerability must at times have been acute” (120). Staunchly surviving such trials and tribulations, Ezekiel went on to create celebrated works such as his statue of Jefferson that was installed at the University in Charlottesville.

This success directly led to the commission for one of his most famous works, the Confederate monument at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia, of which Nash’s book contains a handsome illustration. Despite such late successes, Nash links Ezekiel’s final years elegiacally to the decline of the prewar empires and expiration of the fragile milieu in which this artist, like others, flourished. Italy’s involvement in World War one, which cost hundreds of thousands of Italian lives, also resulted in the shortages that, Nash suggests, led to Ezekiel’s death. Lacking sufficient fuel to heat his studio during the cold damp Roman winters, Ezekiel contracted a case of pneumonia “from which he was not to recover” (151). The outpouring of public grief at his death and eulogies about his life are a testament to Ezekiel’s high standing in the artistic and cultural circles of early twentieth-century Europe. Nash’s cultural biography is evidence that the twenty-first century renewal of interest in Ezekiel’s life and work is well underway. The author, in addition to detailing his subject’s many achievements as an artist, succeeds in portraying Ezekiel as a true cosmopolitan, fully deserving of the epithet Nash bestows, “a bona fide citizen of the world” (xiii).

Bibliography

Nash, Peter Adam. The Life and Times of Moses Jacob Ezekiel: American Sculptor, Arcadian Knight. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2014.

Last modified 3 December 2014