The following passage from Hatton's Club-Land comes from the Internet Archive version of a copy in the University of Toronto Library. George P. Landow has formatted it, adding links. Click on images to enlarge them and to obtain additional information about them.

n the old days the members

stood at the window to ogle, and the fine ladies went by on both sides of the

street to be ogled. In the early days of Walpole and Addison, White's was

close to St. James's Palace (see photograph at right), and the life of the street is well shown in the

pictures of the time. Contrasted with the modern street the change is

startling. There were notable clubs before Brooks's, Boodle's, White's, and

Arthur's, and if one were professing to write a history of clubs they would

have to be mentioned. White's has a curious history. It is the outcome of

White's Chocolate House, 1698, which stood a few doors from the bottom

of the west side of St. James's Street. There was a small garden attached

to the house. Doran says "that there more than one highwayman took

his chocolate, or threw his main, before he quietly mounted his horse

and rode down Piccadilly towards Bagshot." The house was burnt down

in 1733. The King and Prince of Wales were present, and encouraged the

firemen by words and guineas in their efforts to subdue the flames. Cunningham says, "The incident of the fire was made use of by Hogarth in

Plate VI. of the Rake's Progress, representing a room at White's.

n the old days the members

stood at the window to ogle, and the fine ladies went by on both sides of the

street to be ogled. In the early days of Walpole and Addison, White's was

close to St. James's Palace (see photograph at right), and the life of the street is well shown in the

pictures of the time. Contrasted with the modern street the change is

startling. There were notable clubs before Brooks's, Boodle's, White's, and

Arthur's, and if one were professing to write a history of clubs they would

have to be mentioned. White's has a curious history. It is the outcome of

White's Chocolate House, 1698, which stood a few doors from the bottom

of the west side of St. James's Street. There was a small garden attached

to the house. Doran says "that there more than one highwayman took

his chocolate, or threw his main, before he quietly mounted his horse

and rode down Piccadilly towards Bagshot." The house was burnt down

in 1733. The King and Prince of Wales were present, and encouraged the

firemen by words and guineas in their efforts to subdue the flames. Cunningham says, "The incident of the fire was made use of by Hogarth in

Plate VI. of the Rake's Progress, representing a room at White's.

Plate VI, the gaming house scene from Hogarth's The Rake's Progress, which he supposedly based on White's.

The total abstraction of the gamblers is well expressed by their utter inattention to the alarm of the fire given by watchmen who are bursting open the doors." In the first number of The Tatler it is promised that "all accounts of gallantry, pleasure and entertainment shall be under the article of 'White's Chocolate House.'" Originally the house was public. It became a private club in 1736. Among the members were the Earls of Cholmondeley, Chesterfield, and Eockingham; Sir John Cope, Major-General Churchill, Bubb Doddington, and Colley Cibber.

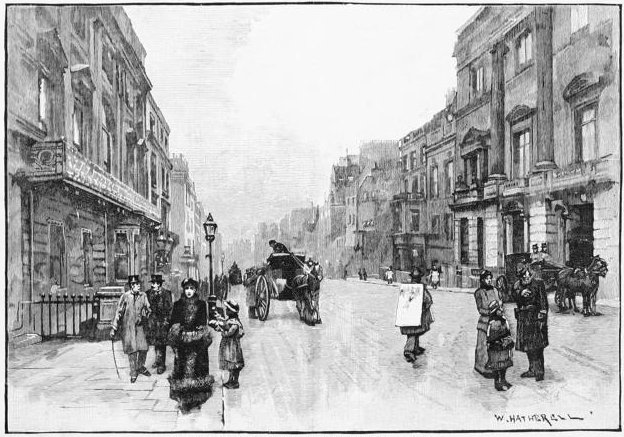

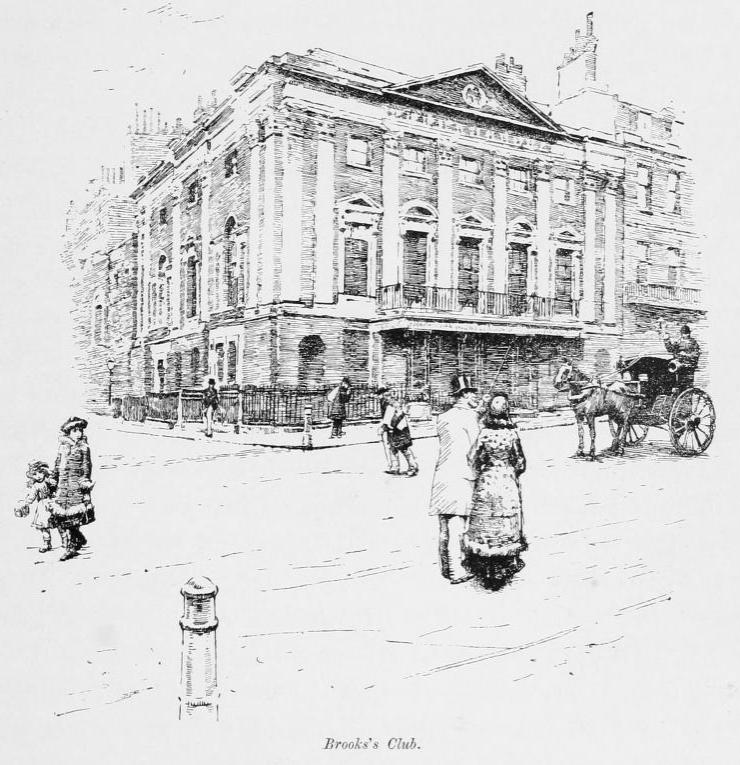

Left: St. James's Street. Showing White's and the Devonshire Clubs. Right: Brooks's Club.

A gambling-house at first. White's for many years had a bad reputation. Pope, in the "Dunciad, has a shot at it —

"Or chaired at White's, amidst the doctors sit,

Teach oaths to gamesters, and to nobles wit."

If Brooks's is, as Mark Lemon in his "Up and Down the London Streets" says, "probably the most aristocratic of London clubs," time was when White's was the fashionable club of the town; and it still holds a distinct and enviable position, though some of its members think the Turf and the Marlborough more amusing. "The men at White's," an old habitue tells me, "still belong to the higher ranks of club men, and it is a pleasant thing in the season, before dinner, to listen to the veterans who occupy the two arm-chairs in the window, talk sports and pastimes, wars and rumours of wars, and discuss current gossip." Dinner at White's is a ceremonial business, wax-candles, stately waiters, carefully decanted wine, courses that come on with procession-like solemnity, a long sitting over the wine, and with the older men a "whitewash" of sherry before your coffee and cigar. The old "bet-book" is still preserved and used. Walpole mentions it in a letter of 1748, and in no very complimentary terms. "There is a man about town. Sir William Burdett, a man of very good family, but most infamous character. In short, to give you his character at once, there is a wager entered in the bet-book at White's that the first baronet that will be hung is this Sir William Burdett."

There are still some curious and interesting bets registered at White's, dealing as in the past with love and marriage, with horse-racing and with politics. Some of the modern entries in the bet-book are as eccentric as those that fill the earliest volumes. Mark Twain, when he described the speculative character of "thish-yer Smiley," who would bet on anything, had probably never heard of White's, though the members of that ancient institution, when in their own house, were all Smileys.. . .[T]he men at White's not only betted on anything and everything, but registered their transactions in black and white. They betted on births, deaths, and marriages, the length of life of their friends or of a ministry, "on the shock of an earthquake or the last scandal at Eanelagh or Madame Cornelys's." They were as grim in their premeditated bets as Smiley in his thoughtlessness . . . "A man dropped down at the door of White's, he was carried into the house. Was he dead or not? The odds were immediately given and taken for and against. It was proposed to bleed him. Those who had taken the odds that the man was dead, protested that the use of the lancet would aflfect the fairness of the bet."

White's removed to its present site in 1755, into the house previously occupied by the Countess of Northumberland, widow of the tenth Earl. Walpole says, "She was the last who kept up the ceremonious state of the old peerage." She died in 1688. "When she went out to visit, a footman, bareheaded, walked on each side of her coach, and a second coach with her women attended her."

It would be odd if our present White's did not suggest to a visitor some thing of the starchy affectation of "the good old days." [8-11]

Bibliography

Hatton, Joseph. Clubland London and Provincial. London: J. S. Vertie, 1890. Internet Archive version of a copy in the University of Toronto Library. Web. 1 March 2012.

Last modified 1 March 2012