According to the Oxford English Dictionary initially the term folly meant "any costly structure considered to have shown folly in the builder."Follies served as popular adjuncts to the landscape in the eighteenth century — for example, Severndroog Castle on Shooter's Hill outside London in Castle Wood, a sham mediaeval tower, sixty feet in height, designed in 1784 by architect Richard Jupp – featuring a hexagonal turret at each corner. Throughout the eighteenth century fanciful landowners had such pseudo-ruins, gothic castles, and chinoiserie constructed all over the British Isles.

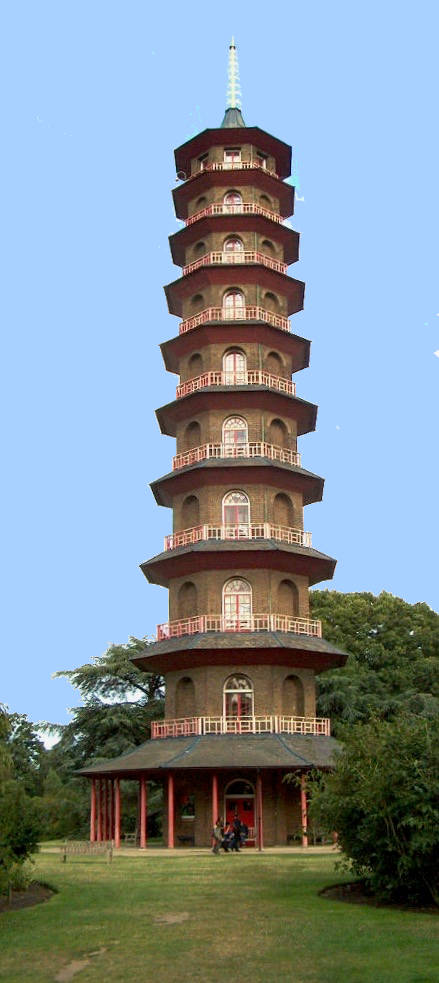

The Grand Pagoda at Kew

The Grand Pagoda at Kew, designed by Sir William Chambers [1762].

One of the most celebrated survivals of this rage for the outlandish is the Grand Pagoda at Kew Gardens, near London. A gift for Princess Augusta, the founder of the botanic gardens at Kew Gardens, the Great Pagoda occupies the south-east corner, and was the first building to offer an ariel prospect of Greater London. Designed by fashionable architect Sir William Chambers and erected in 1762, the ten-storey octagonal structure is 163 feet high (nearly 50 metres). The lowest of the ten octagonal storeys is 15 metres (49 feet) in diameter. From the base to the highest point is 50 metres (164 feet). Although it once served no purpose other than an ornate lookout, during the Second World War holes cut into each of 252 steps in its central staircase were used to drop-test of model bombs to be dropped from military aircraft.

A key feature currently under restoration is the eighty dragons which originally adorned the roofs, each carved from wood and gilded. Removed in 1784 after rot set in, the dragons were rumoured to have been sold to settle George IV’s gambling debts.It was originally flanked by a Moorish Alhambra and a Turkish Mosque, the kinds of follies that were in vogue in the planned gardens of eighteenth-century Europe. Although to ensure good luck a genuine Chinese pagoda would have an uneven number of floors, the Kew specimen one has just ten. The famous fifteenth-century Porcelain Tower in Nanking, China supposedly inspired Chambers. Although he probably had not seen the original building, he may have based his design on an engraving which erroneously shows just ten floors. Later in the eighteenth century, such garden follies became even more exotic, representing other parts of the world, including Chinese pagodas, Japanese bridges, and Tatar tents as British government officials, merchants, and military personnel returned home from missions to Asia and Africa and had a desire to replicate the exotic buildings they had seen abroad.

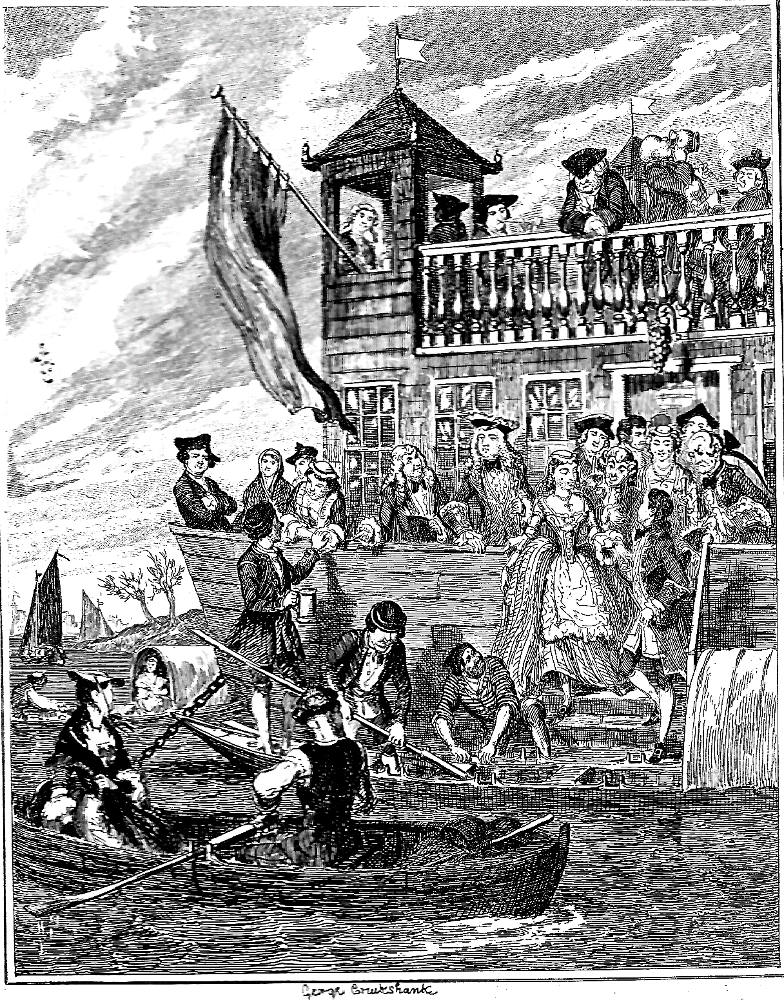

The Folly on the Thames

Illustration for Ainsworth's The Miser's Daughter by Cruikshank [March 1842].

The popular author William Harrison Ainsworth introduced Victorian readers to a seventeenth-century folly that was no longer in existence, although The Folly on the Thames that the antiquarian-novelist has worked into the story of The Miser's Daughter (1842) is not really a folly, for such a building should be a structure without a real purpose other than to complement the landscape. More characteristic is the Sydenham folly, which appears to be a ruined mediaeval church or monastery.

The particular folly that serves as Ainsworth's backdrop was a "floating house of entertainment" in The Miser's Daughter (1842) dating from the reign of Charles the Second. According to the website Almay, this folly “was a floating house of entertainment in the reign of Charles II on the Thames between London and Westminster. Originally a musical summerhouse attracting the elite it descended into drunkenness and harlotry.” Eventually, falling into disrepute and disrepair, "The Folly" was chopped up for firewood in 1784.

It is unlikely, therefore, that either the book's illustrator, George Cruikshank, or Ainsworth had actually seen the folly on the Thames, although the specificity of their descriptions suggests that they may have been able to study a print or drawing of it. In order to accommodate this broad building to his narrow plate, Cruikshank has selected a corner of the folly, and is describing the scene from one side as the young Haymarket actress, Kitty Conway (at the top of the stairs), arrives, assisted by a fashionably dressed youth who sets the tone for the river scene in The Folly on the Thames (1842). In an 1872 letter to the Times Cruikshank asserted that, since part of his design in illustrating the Ainsworth novel was to allow "the public of the present day to have a peep at the places of amusement of that period, I took a considerable pains to give correct views and descriptions of those places" (published 8 April 1872; cited in Patten, p. 167). The illustration of the Thames Folly exemplifies the "pains" that Cruikshank took to re-create London of the 1740s.

References

Ainsworth, William Harrison. The Miser's Daughter: A Tale. With 20 illustrations by George Cruikshank. First published in 3 volumes by Cunningham and Mortimer, London, 1842. London, Glasgow, and New York: George Routledge, 1892.

"The Condition of the People." John Cassell's illustrated history of England. Volume 3. Page 621.

"The Folly on the Thames." Alamay. Accessed 10 June 2018. https://www.alamy.com/stock-photo-the-folly-on-the-river-thames-17th-century-floating-house-of-entertainment-176201596.html

Khederian, Robert. "The Whimsical World of Garden Follies — Built to Impress." Curbed. 12 October 2017. https://www.curbed.com/2017/10/12/16460128/garden-follies-highclere-kew-england-chinoiserie

Minott-Ahl, Nicola. "Building Consensus: London, the Thames, and Collective Memory in the Novels of William Harrison Ainsworth." London Literary Society. Accessed 11 June 2018. http://literarylondon.org/the-literary-london-journal/archive-of-the-literary-london-journal/issue-4-2/building-consensus-london-the-thames-and-collective-memory-in-the-novels-of-william-harrison-ainsworth/

Patten, Robert L. George Cruikshank's Life, Times, and Art, vol. 2: 1835-1878. Cambridge: The Lutterworth Press, 1992.

"The River Thames: Part 1 of 3." "Chapter 37: The Thames." Old and New London: Volume 3. London: Cassell, Petter & Galpin, London, 1878. HBO: British History Online. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/old-new-london/vol3/pp287-299.

Vann, J. Don. "The Miser's Daughter in Ainsworth's Magazine January-October 1842." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: MLA, 1988. Pp. 22-23.

Last modified 18 June 2018