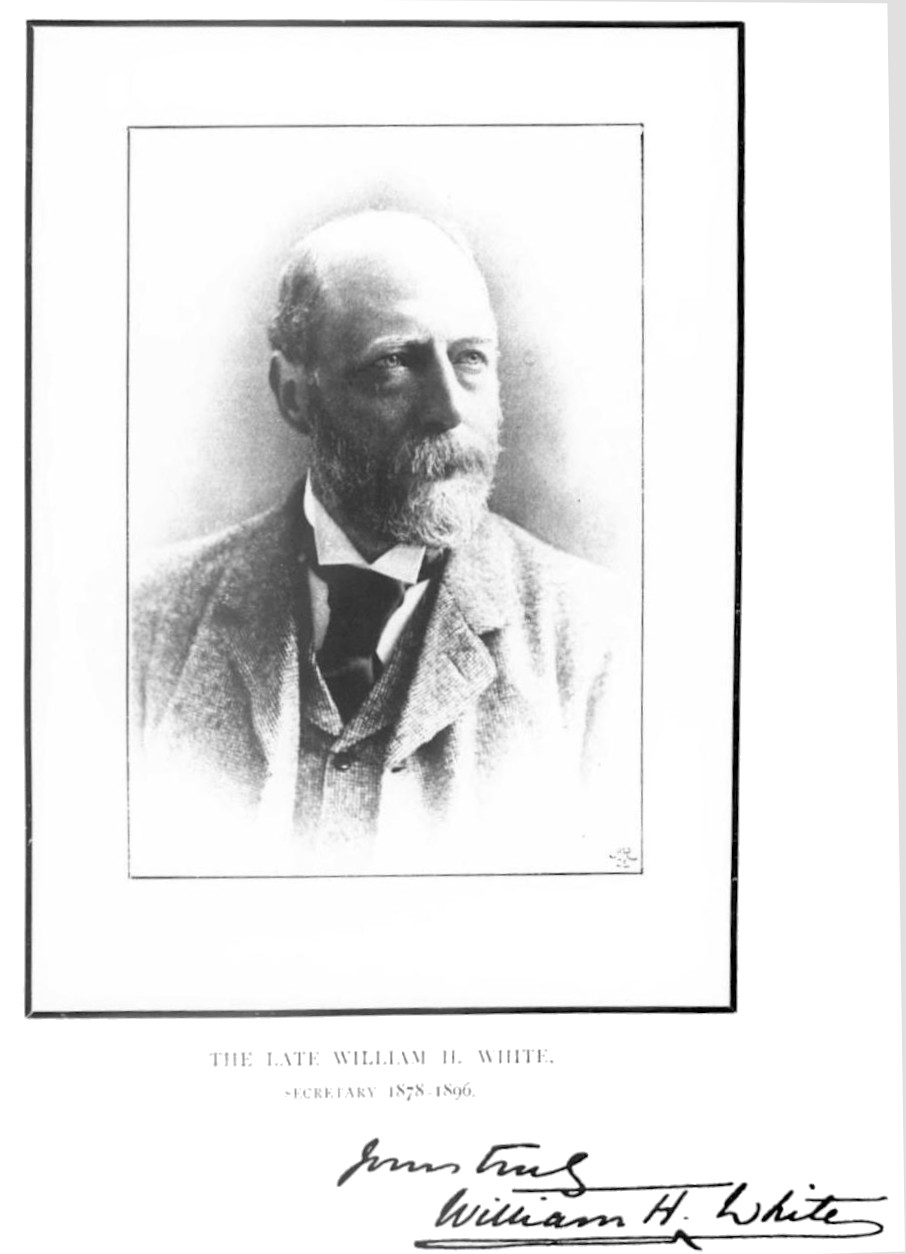

William Henry White, Fellow, Eighteen Years Secretary of the Royal Institute of British Architects. Born January 1838; died October 1896.

THE unobtrusive lives of most men who are devoted to intellectual pursuits attract little attention from the world generally. In these days of unseemly advertisement, when a flourish of trumpets too often heralds the personality rather than the work, the quiet labours of a thoughtful man are apt to be passed by unnoticed. Indeed, it may be said that men are to be found in all communities, with definite aims and actuated by high motives, for whom not one thought is spared to the value of their work or the influence they may exercise in the progress of mankind. The great centres of intellectual training, the learned societies, and the universities in all parts of the civilised world, are the home of the type of humanity which finds its chief pleasures in the higher ranges of mental occupation. Of such was our late lamented colleague, William H. White, for eighteen years Secretary of this Institute, who died on the 20th October, after an illness extending over several months. He was followed to his grave in Nunhead Cemetery, two days afterwards, by those who knew his worth and his labours, and with whom he had so long worked and striven in intimate association.

In the brief obituary notice in The Times of the 22nd October it was said that diligence and unbounded activity marked his career. To these commendable qualities should be added a long course of honourable conduct, persistence in the faithful discharge of his duties, and a devotion to the Institute that knew no limits. White commenced professional life with but little extraneous help. On the completion of his articles in London with George Morgan, he crossed the Channel, and, after a short term in the office of a French architect, established himself in Paris with a view to permanent residence. Fortune soon began to look kindly on the young Englishman located on foreign soil, and influential clients came to his door. For the Baron Fernand de Schickler he reconstructed a large portion of his Chateau de Bizy, once a favourite residence of Louis Philippe; and the Baron Arthur de Schickler entrusted him with extensive additions to the Chateau de Martinvast, near Cherbourg. He was also engaged [11/12] upon some interesting work at an old chateau near Bourges, belonging to Prince Auguste d’Arenberg. These and a number of minor works seemed to secure for him a promising future. But the Franco-German War broke out, and shattered his hopes at a blow. His wealthy clients, who were mostly of German extraction, abandoned all building operations and quitted France, leaving poor White to pack up his effects and make his way back to England. And here must be recorded a touching incident in his career. Taking a last farewell look round the room which had served as his studio during a few happy years, instinct inspired him with the idea of laying all his drawings and materials on one table and covering them over with the Union Jack. In the following year, when quiet once more reigned within the walls of Paris, White visited his old room, and, to his surprise, found everything untouched and the covering flag undisturbed.

Nothing daunted by the necessity of starting once more in professional life, White sailed for India, and, taking advantage of his father’s long connection there as a member of the Bengal Medical Service, entered the Public Works Department of the Indian Government. Here, again, his marked ability and diligence soon brought him into note, and important buildings, such as the Court of Small Causes at Calcutta (illustrated in The Builder, 23rd March 1878), the Monument to Chief Justice Norman, and the Presidency College were committed to his charge. After travelling in India and on the Continent, White returned to London and took up journalistic work, for which he had special qualifications. His contributions to The Builder at that period, in the form of reviews or original articles, are numerous enough, and are all stamped with an amount of research that would do credit to any writer in the highest ranks of literature. About this time he was appointed the Examiner in Architecture at the Royal Indian Engineering College, Cooper’s Hill, a post he occupied for about two years. And now came the turning-point in his career. The Secretaryship of this Royal Institute became vacant in 1878 through the retirement of Charles Eastlake, the present Keeper and Secretary of the National Gallery. White’s eminent qualifications at once secured him the post. It is difficult to tabulate his official work in Conduit Street, or to enumerate his able services during a long term of eighteen years—an era in the progress of the Institute marked by increased influence at home and abroad, and a necessarily more extended system of administration. A glance at any of the official publications at the period when White entered upon his duties, put in comparison with any recent number of the Journal, or a volume of the Transactions issued till within the last three years, will suftice to show the amount of increased responsibility imposed upon the Secretary as Editor of all the Institute publications.

There were two influences in White’s career which, more or less, seemed to govern his course of action. Perhaps his sojourn in Paris was the more potent. Adapting himself to French methods, moving freely amongst architects of repute, and regarding with admiration their systems of artistic and professional education, White brought with him to England ideas which he could never shake off. His views on many points were frequently foreign to English notions and methods, but the knowledge that he had acquired proved of infinite service in the transaction of his official duties. Few of his colleagues in this country are aware of the high esteem in which White was held by architects of all European countries, as well as the States of America. His constant correspondence with French architects especially was to him one of his most pleasurable occupations. A facile pen, and a perfect acquaintance with the French tongue and all technical expressions, made him a desired communicant in international matters relating to architecture and architectural practice. Scarcely nine months ago White, not in the best of health (for the seeds of his fatal disease were already sown), went to Paris as the accredited representative of the Institute to take an honoured part in a banquet to M. Charles Garnier on his promotion to the grade of Grand-Officier de la Légion [12/13] d’Honneur. The more than cordial reception given to White on that interesting occasion, when 150 architects and others belonging to the world of Art attended, was due as much to his endeared personality as to his representation of a Body always held in high esteem by our brethren throughout France.

The other influence to which reference has been made was the character of the literature he favoured about the time of his settling permanently in London. White was always a reader. He was so constituted intellectually that he could not but delight himself with the works of his favourite authors. Had White been unsuccessful in obtaining the Secretaryship, he would, in all probability, have drifted permanently into journalism. With this idea in view he took infinite pains to attain style in composition. Among the essayists and other writers of the period he selected for study, no author was more congenial to his taste than Swift, although sserne and Smollett proved almost equally attractive. To the tinge of cynicism that permeates the pages of the gifted Dean may be ascribed that disposition to combativeness and satire that mars the general excellence of many of White’s well-studied compositions. Anyhow, his love of literature and books, and his special interest in the growth and extended usefulness of the Institute Library, never failed him. Solely to his endeavours and persistent action the Library has been enriched in recent years by a number of valuable works presented by English and foreign authors and publishers. And, at the last moment, when he felt the end was approaching, a kindly thought prompted him to indite a letter to his brother, as sole executor, with a fond request that all his books and papers relating to architecture might be at the disposal of the Institute he loved so well. But now his work is over, and the long day has closed. The morrow, which in his last lingering hours he was anxiously awaiting — the morrow when he would take his accustomed seat in Conduit Street, conduct his correspondence, and then, in the evening hours, in the Club Library, or in the quietude of his own room, give play to the love of writing something for the advancement of the Institute, will come no more. His book of life has been finished too soon. But any one who cares to turn over its pages will find therein a long record of thoughtful, well-directed work, of unswerving attention to the call of duty, and a devotion to the Institute that has no parallel.

ALEX. GRAHAM.

Note: George Aitchison's Announcement

Before this address, the then President of RIBA, George Aitchison (1825-1910), who had just succeeded to the presidency of the RIBA that year, had formally announced White's death in the previous month, saying that he was really irreplaceable, as "a man of great sagacity and judgment, possessed of excellent business habits, of a capacity for organisation but rarely found, and of great application" (14). In this earlier encomium, printed after the obituary, Aitchison had also praised White's "deep knowledge of architecture and of architectural books," and the way he steered the RIBA during what sounds like a rather fraught period in its "alliances with the Provincial Societies" (14).

It is interesting to note that, in talking about the huge workload involved in White's role, Aitchison had mentioned that by this time the RIBA had nearly 1,600 members in various parts of the world" (14). Aitchison had also praised White for fostering the connection with France, and for boosting the influence of French architectural principles in Britain: Aitchison himself was an architect of eclectic taste, his best-known work having been Leighton House, with its remarkable Arab Hall. In conclusion, Aitchison had read out letters of appreciation and condolence from prominent French and German authorities, and the Dundee Institute; and a resolution was passed that the RIBA's deep gratitude for White's services should be put on record, and its "most sincere" sympathy conveyed to White's brother, Colonel G. A. White, late Commanding 1st South Lancashire Regiment (15). It would seem that there were no other close family members.

That White died before reaching 60 must have contributed to the sense of shock and loss within the profession. — Jacqueline Banerjee

Bibliography

Graham, Alex. "William H. White, Fellow." Journal of the Royal Institute of British Architects Vol. 4, issue 1 (5 November 1896): 11-13; portrait, captioned "The Late William Henry White, Secretary 1878-1896," facing p. 11; Aitchison's announcement, 13-15). Internet Archive. Web. 8 July 2025.

Created 8 July 2025