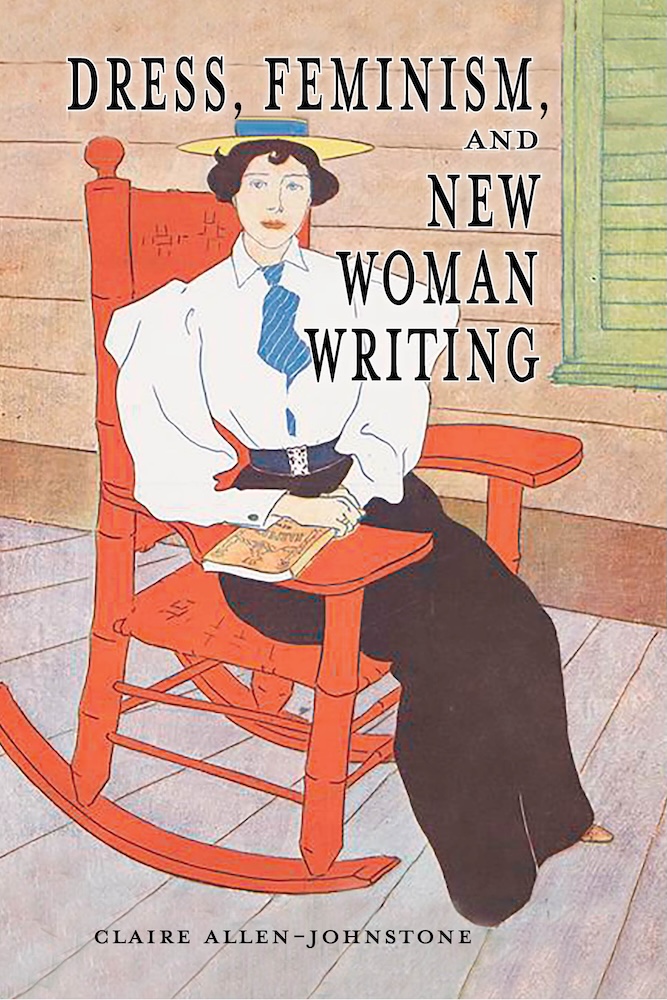

laire Allen-Johnstone's Dress, Feminism, and New Woman Writing is the

latest contribution to the specialized area that links New Woman and

dress culture studies. Women's costume became potent subject matter in

the period's debates about women's rights and women's essential nature.

Combining the literary critic's inquiry with a fashion historian's

detective work, Allen-Johnstone uses an inventive methodology — the

sartorial biography — to generate refreshing insights into the "intricate

sartorial webs" she discerns in works by Olive Schreiner,

Sarah

Grand, George Egerton, and Grant Allen (15). Moving between the engagingly

clear and the muddled, the book investigates the complex meanings about

dress that, according to Allen-Johnstone, her predecessors have

neglected.

laire Allen-Johnstone's Dress, Feminism, and New Woman Writing is the

latest contribution to the specialized area that links New Woman and

dress culture studies. Women's costume became potent subject matter in

the period's debates about women's rights and women's essential nature.

Combining the literary critic's inquiry with a fashion historian's

detective work, Allen-Johnstone uses an inventive methodology — the

sartorial biography — to generate refreshing insights into the "intricate

sartorial webs" she discerns in works by Olive Schreiner,

Sarah

Grand, George Egerton, and Grant Allen (15). Moving between the engagingly

clear and the muddled, the book investigates the complex meanings about

dress that, according to Allen-Johnstone, her predecessors have

neglected.

In creating sartorial biographies for her authors, Allen-Johnstone relies on photographs, personal papers, and previously undiscussed archival materials to illustrate each author's investment in dress reform movements as well as opinions about gender, class, and race. Her experience with fabrics and fashion lets her follow the "sartorial clues" she locates in these materials (17). She also observes how the books' covers reflect on publishers' sales practices that circumvented the circulation libraries' monitoring at a time of their weakening control.

The author trains a keen eye on the "New Woman's look" (18), satirized in periodicals as varied as Punch, or The London Charivari and The Girl's Own Paper, portrayed in poems and plays, advocated by the Rational Dress Society, the Rational Dress League, the Women's Social and Political Union, and the Artistic or Aesthetic Dress Movement. Bloomers, knickerbockers, corsets, veils, gloves, shoes — all became fraught signifiers for the New Woman as she bicycled, walked, and danced through Victorian and Edwardian England's literal and imaginative terrains. The fevered attention stretched far beyond Great Britain. Allen-Johnstone includes significant references to American first-wave feminism and movements in the empire as well. One of several powerful images displaying the broad use of dress to signify the New Woman is a 1894 photograph, "A Bride in Breeches," shows the bride and her attendants garbed in trousers at a ceremony performed by the New Zealand Dress Reform Association (21).

Disappointingly, the book's literary analysis does not maintain the introduction's briskness or the sartorial biographies' vitality. A determined explicative resolve overwhelms each chapter's argument; frequently, we must sift through an array of details. More stringent attention to paragraphs' internal coherence and transitions between paragraphs would have highlighted more forcefully the claims about how a character's "sartorial journey" (74) or "sartorial fortunes" (195) registered the New Woman writer's views about performative gender, social purity, women's suffrage, and so forth. "Sartorial" modifies more than twenty-five nouns, providing colorful denotation but sometimes gussying up obvious, even well-worn points. The lexicon wears a little thin. An affection for purple phrasing diminishes the analytic command as this oddly occult sentence illustrates: "Dress was used strategically but not always seamlessly, and often contradictory clothes seem to have slid into New Woman texts, and wardrobes, unbeknownst to the author" (38).

Chapter 1, "Olive Schreiner: Disruptive Dress" asserts that, contrary to the main line of scholarship on Schreiner, she is not "the straightforwardly anti-fashion, anti-racist writer"(83) scholars usually take her to be. Allen-Johnstone traces Schreiner's intricate relationship with dress across various works, with particular focus on her first published, semi-autobiographical, and "anti-luxury" (96) novel, The Story of an African Farm (1883) which appeared under the pseudonym, "Ralph Iron," a cross-dressing mode for Allen-Johnstone. Pairing it with the posthumous From Man to Man: Or, Perhaps Only (1926) allows Allen-Johnstone to explore Schreiner's changing attitudes toward dress reform, her support for women's independence, and her fraught views about the Boers and Black South Africans. As a child in South Africa, Schreiner fancied boys' clothing and nudity (Allen-Johnstone awkwardly calls the latter "undressing" [46]); as a celebrity author in England, Schreiner relished feminine frills and tightly-laced dresses, the high fashion of affluent white women. Unlike The Story of an African Farm, From Man to Man ratifies "an alternative dress code" (80). Allen-Johnstone supplements the wardrobe evidence with excellent details from Schreiner's letters, feminist tracts, From Man to Man's earlier variants, and Schreiner's 1926 semi-autobiographical novel Undine to show her increasing feminist commitment even as her views about class, race, and ethnicity remained less progressive.

Allen-Johnstone's analysis extends even to the design of these books. Chapman and Hall's elaborate cover for The Story of an African Farm tempted readers with its gold script and exotic golden ostrich. The London publisher Hutchinson & Co. acquired the book in 1893 and adopted the floral designs that would eventually become associated with proto-feminist and New Woman fiction. In contrast, the frontispiece of T. Fisher Unwin's edition of From Man to Man enclosed the smock-clothed Shreiner photograph within a simple binding embellished with her gold-lettered signature. For Allen-Johnstone, the binding's materiality emblematizes Schreiner's dual sartorial impulses. Schreiner was "anti-fashion, even anti-clothes" but conscious of the way beautiful clothes create a favorable impression (50). Studio photographs captured Schreiner's ever more radical Artistic Dress style, especially apparent in her choice of a loose-fitting smock-like dress, a garment symbolic of men's manual or artistic labor (54). The photographs' generally dim reproductions do not hinder either Allen-Johnstone's analytic vigor or her robust claim that Schreiner's "sartorial rebelliousness" (49) finds expression in her fiction's complicated and nuanced views.

With Chapter 2, "Sarah Grand: ‘How Important Dress Is!'," Allen-Johnstone's riveting archival evidence shows Grand's developing class awareness and social reformist activity. Grand felt ambivalent about early feminist activism which she believed required an attitude of "appeasement" (112) to counter hostile misperceptions about New Woman masculinity and to ensure the movement's successes. Here as elsewhere, biographical details lead the way. Grand, Allen notes, loved the fashionable and the fancy; the lofty register of her pseudonym, adopted in 1891 after she left her husband, and which she used in her personal life, evinced her love for privilege. She even had the name engraved on a silver powder case.

Allen-Johnstone shows how details of sartorial biography clarify what might seem inconsistent in Grand's novels. Scrupulous integration of Grand's short stories, interviews, tracts, and novels throughout this chapter produces a densely persuasive exploration of an author whose vexed feelings about dress reform mingled with the "strategic importance of people-pleasing" (140). However, the literary explication presents considerable challenges for readers. Grand's The Heavenly Twins (1893) has generated a small cottage industry in feminist criticism, led by those like Gail Cunningham, Teresa Magnum, and Anne Heilman. Allen-Johnstone's own lengthy treatment, combined with frequent turns to The Beth Book (1897), increases the imprecision of her analysis. Both narratives feature large casts of characters and sweeping scopes of action; both cry out for clearer identification and more efficient contextual grounding. At the same time, the abundant textual detail threatens to obscure the analysis. The chapter devotes special attention to Angelica Hamilton-Wells' cross-dressing and her masquerade as "Boy" in The Heavenly Twins. Allen-Johnstone argues that, as with her later drafting of feminist speeches, Angelica's cross-dressing phase communicates women's superiority because it permits them simultaneously to inhabit and identify with strengths that are stereotypically masculine and those that are traditionally coded as feminine.

Turning again to book design, Allen-Johnstone closes the chapter by briefly examining the different book covers of The Heavenly Twins, finding that W. M. Heinemann's 1893 edition "sugar-coated" (156) the book's feminist content with its graceful floral designs. In 1912, Hodder and Stoughton's cover depicted Angelica dressed in a man's vest, suit jacket and trousers, with her long hair tumbling seductively over her shoulders. Grand would have enjoyed the design, Allen-Johnstone speculates, a final conjectural frill for a tricky chapter.

In the next chapter, Allen-Johnstone analyzes two stories by another favorite New Woman writer, George Egerton. "A Cross Line," from Egerton's collection Keynotes (1893), and "Gone Under" from Discords (1894), complicate the traditional view of Egerton as someone who "thought in black and white ways." According to Allen-Johnstone, attending to dress in these stories reveals the complexity of Egerton's questions about personal identity, morality, and women's roles; these stories prove the "multiple interests of this multifaceted writer" (166). Whereas Grand's impoverished childhood fueled her adult pursuit of luxury and high fashion, Egerton's established an unwavering allegiance to "egalitarian values," as reflected in her portrayals of the less privileged female characters she favored in her work (170). Sadly, Allen-Johnson neglects commentary about the short story's place in late Victorian publishing. Allen-Johnstone's claim that "[a]ddressing dress reform through glancing references was typical of the New Woman short story, where the space available was so limited" (185) suggests unfamiliarity with current energetic scholarship by D'hoker and Eggermont (2015), for instance, or Liggins, Robbins, and Maunder (2011) on a genre whose explosive popularity offered authors, including New Woman authors, tremendously lucrative opportunities.

Analyzing "A Cross Line," Allen-Johnstone traces Egerton's complex thoughts about the dynamics of gender and power, women's sexual desires, and ambivalence about marriage. Allen-Johnstone's close reading of the garments in the tale's opening attests to the female protagonist's passionate nature, as does the later explication of her voluptuous Orientalist fantasy. Although the protagonist of "A Cross Line" declines infidelity's temptations and embraces her anticipated maternal role, the story avoids conventional domestic closure, ending with a moment of class solidarity between the protagonist and her servant Lizzie, when their hushed and gently intimate examination and exchange of baby garments reflects a shared understanding of maternal love. "Gone Under" demonstrates Egerton's attention to women from society's less privileged. Unfortunately Allen-Johnstone, by focusing on color symbolism and wardrobe niceties, obscures Egerton's nuanced and contradictory views and denies this deeply troubling story about women's exploitation even a clear description of the plot.

Elliott and Fry, “George Egerton,” “Women in the Queen’s Reign: Some Notable Opinions,” The Ludgate 4 (June 1897): 213-17, 216.

The nuance and contradiction obscured by Allen-Johnstone's analysis of the texts finds clearer expression in her analysis of Egerton's dress and the design of her books. To take these one by one: There are "telling dualities" (195) in Egerton's wardrobe. Although Egerton, knowing color symbolism's clout, donned a feminine white when she first visited her publisher at The Bodley Head, her more tailored look and signature pince-nez troubled the public's perception since the more mannish associations conflicted with typical female identity. In a discerning close-reading of an 1894 Review of Reviews illustration, Allen-Johnstone points out its conflicting signals to Egerton's "difference feminism" (176). The Ludgate's 1897 illustration of the pince-nezed Egerton shows her dressed in softer garb — perhaps, Allen-Johnstone hypothesizes, a modified wardrobe choice in response to another earlier caricature by Punch in 1894. Lively attention to Egerton's cross-dressing pseudonym enhances this discussion. The name was not merely a professional mask but one Allen-Johnstone suggests possibly honored two earlier "Georges," Sand and Eliot. In an 1894 letter, Egerton explained how she blended her husband's first and her mother's maiden names, bringing a sentimental and deeply personal tenor to the name's masculine connotations. The pseudonym's charm extended into all aspects of Egerton's life; John Lane himself opened many letters to her with "Dear George" (175).

Allen-Johnstone finds a similar duality in both collections' covers. Challenging Margaret Stetz's reading of the cover of Keynotes, she says Beardsley assigns its sole female figure greater phallic power than the two small male figures sandwiched below the book's title. The beautiful slipcover Egerton embroidered for Lane's presentation copy further trumps Beardsley. Its delicate flowers and "GE" on a satiny fabric combine the sensually tactile with disciplined feminine skill, representing Egerton's feminist beliefs about autonomy, personal identity, and self-fashioning. Disappointingly, Allen-Johnstone allots Beardsley's cover design for Discords a mere four sentences in a paragraph dominated by conjectural thoughts about the publisher's turn to simpler floral motifs strewn across a plain background.

Cover of Discords (1894; London: John Lane; Boston: Roberts Bros.). Photograph used with permission by Capitol Hill Books, Washington, D.C.

In the fourth chapter, "Grant Allen: From the White-Clad Free Lover to the Typist in a ‘Little Black Dress'," Allen-Johnstone seeks to rehabilitate the writer from his reputation as the "worst of the worst in terms of men contributing to New Women writing" (207). Rather, Allen-Johnstone sees great parity in male and female New Woman authors' feminist use of dress. But the argument here is unconvincing. Descriptive references taken from Gissing and Hardy are without meaningful explanatory or evidentiary impact, and the author's frequent nods to Egerton and Grand stall rather than deepen the discussion. However, Allen-Johnstone does succeed in explaining Allen's evolving, progressive attitudes toward free union, dress reform, and women's employment via his various articles, tracts, and books. This lavish textuality solidly frames the chapter's two examples: The Woman Who Did, first published in John Lane's Keynote Series in 1895, and The Typewriter Girl (1897) by C. Arthur Pearson. Allen-Johnstone contextualizes these materials with analysis of two contemporary texts at the crossroads of psychology and aesthetics. Allen's Physiological Aesthetics (1877) and The Colour Sense (1892) play pivotal parts in the discussion while echoing Allen-Johnstone's inclusion, in the introduction, of Havelock Ellis's The Colour Sense in Literature (1896). Allen-Johnstone additionally shows how an early (and overlooked) short story by Allen, "The Emancipated Woman," contains a "prototype free lover" (216) who foreshadows Herminia Barton in The Woman Who Did.

Early in The Woman Who Did, Herminia's richly ornamented costumes epitomize Artistic dress, a mode Allen regarded favorably. This costume proves her a woman of sophisticated good taste and feminine elegance, a common strategy that stymied hostile attitudes toward the New Woman as excessively masculine. Allen also dresses his free-union protagonist in white, the color associated with sexual purity. While this was a typical New Woman authors' tactic as highlighted throughout the book, it was a symbolic use, I hazard, not peculiar to these authors nor fin-de-siècle Britain. Color theory evidence also discloses contradictions in Allen's fiction and suggests his underlying racist and classist attitudes. Like other New Woman authors, he was not free of period biases.

The Woman Who Did was met by highly negative criticism, exemplified by the barbed condescension of an 1895 review by Millicent Garrett Fawcett. Stung by this, and "likely mortified" (209) by E.T. Reed's Beardsley-esque 1895 illustration for Punch, a parody entitled "The Woman Who wouldn't Do (She-Note Series)," Allen shifted his symbolic approach to clothing in his 1897 New Woman novel, The Typewriter Girl. Perhaps in homage to Schreiner, he also adopted the pseudonym "Olive Pratt Rayner." Allen-Johnstone speculates that this book's more positive reception may have confirmed his skepticism about contemporary beliefs relating to gender and sexual difference absolutes.

Julia Appleton, protagonist of The Typewriter Girl, represents the professional woman who works in the male-dominated world. The analysis points to Allen's bias toward women from the more affluent classes, as shown by his deployment of sartorial details such as Julia's "everyday clothes" (229), the trousers she wears for bicycling, and, most especially, the "smart," crisply tailored black dress she wears to work at the office. No longer the "free-loving feminist associated predominantly with unrealistic white outfits" that scandalized Victorian readers, Allen's heroine is now a skilled typist, an appealing foil to both Elsie, her working-class friend and an accomplished seamstress, and the aristocratic and over-adorned woman Meta, engaged to Julia's employer (228). Nonetheless, Julia does not turn up her nose at the opportunity to wear elegant evening dress, delighting in the gown's clinging folds and the flowers tucked into her hair.

The argument weakens here, as Allen-Johnstone neglects attributing the floral binding of Lane's 1895 edition to Beardsley, and while she includes C. Arthur Pearson's 1897 cover for The Typewriter Girl, the visual contrasts she wishes to highlight, between artist renderings of Herminia and Juliet and the closing assertions about Allen's evolving feminist agenda, limply iterate the general observation that there is "substantial overlap between New Woman texts written by women and those by men" (242).

"Dress," Allen-Johnstone declares, "plays an important role across feminist literature broadly" (255). While she is a savvy cataloguer of the fashion thematic and the period's literature, her organizational strategy of binding all together via common "sartorial strands" (250) often dulls rather than sharpens how the fictions, "rich with sartorial moments," interrogate concerns about female autonomy and gendered cultural norms (75). Ultimately, this absorbing study deserved assiduous editorial guidance to trim the unnecessary repetitions, simplify awkward phrasing, and streamline overly granular explication. Lacking that, Allen-Johnstone's expertise, ambition, and knowledge seem indecisive and disorganized, a great disservice to an otherwise valuable study that testifies, most superbly, to the cherished intimacy a scholar cultivates when, seated before an author's letters, diaries, and personal ephemera, she meets that writer in the quiet space of a library's special collections.

Links to Related Material

- Victorian fashion and the growth of sporting activities, 1850-1900

- Rational Fashion — Review of Don Chapman's Wearing the Trousers and Kat Jungnickel's Bikes and Bloomers

- Dangerous to Their Health — Review of Alison Matthews David's Fashion Victims: The Dangers of Dress Past and Present

Bibliography

[Book under review] Allen-Johnstone, Claire. Dress, Feminism, and New Woman Writing. Amherst, NY: Cambria Press, 2025. Hbk. 319 pp. ISBN 978-1-63857-196-4. $114.99.

Cunningham, Gail. The New Woman and the Victorian Novel. London: Macmillan, 1978.

D'hoker, Elke and Stephanie Eggermont. "Fin-de-siècle Woman Writers and the Modern Short Story." English Literature in Transition, 1880-1920 58, no. 3 (2015): 291-312.

Heilmann, Ann. "Narrating the Hysteric: Fin-de-Siècle Medical Discourse and Sarah Grand's The Heavenly Twins (1893)," pp. 123-135. The New Woman in Fiction and in Fact. Eds. Angelique Richardson and Chris Willis. London: Palgrave, 2001.

Liggins, Emma, Andrew Maunder, and Ruth Robbins. The British Short Story. Houndsmill, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

Mangum, Teresa. Married, Middlebrow, and Militant: Sarah Grand and the New Woman Novel. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1998.

Stetz, Margaret. "Keynotes: A New Woman, Her Publisher, and Her Material." Studies in the Literary Imagination 30, no. 1 (Spring 1997): 89-106.

Created 20 October 2025

Last modified 13 November 2025