Click on the images for larger pictures and more information; click on the links, too, for more information from our own website.

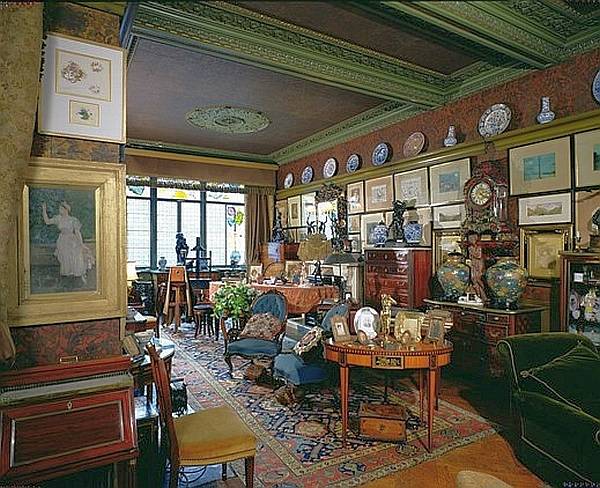

o step off the streets of modern-day Kensington into the cosy domesticity of 18 Stafford Terrace is to travel back in time to the world of our Victorian ancestors. Home of the Punch cartoonist Linley Sambourne, his wife Marion and their two children, the property was handed down in the family until it was purchased by the Greater London Council in 1979 and opened to the public by the Victorian Society as a museum the following year. Substantially unchanged since the close of the nineteenth century, Sambourne House (as it is now known) offers the visitor a unique encounter with what a middle-class family home would have looked like in an increasingly fashionable part of west London during the latter days of Queen Victoria’s reign.

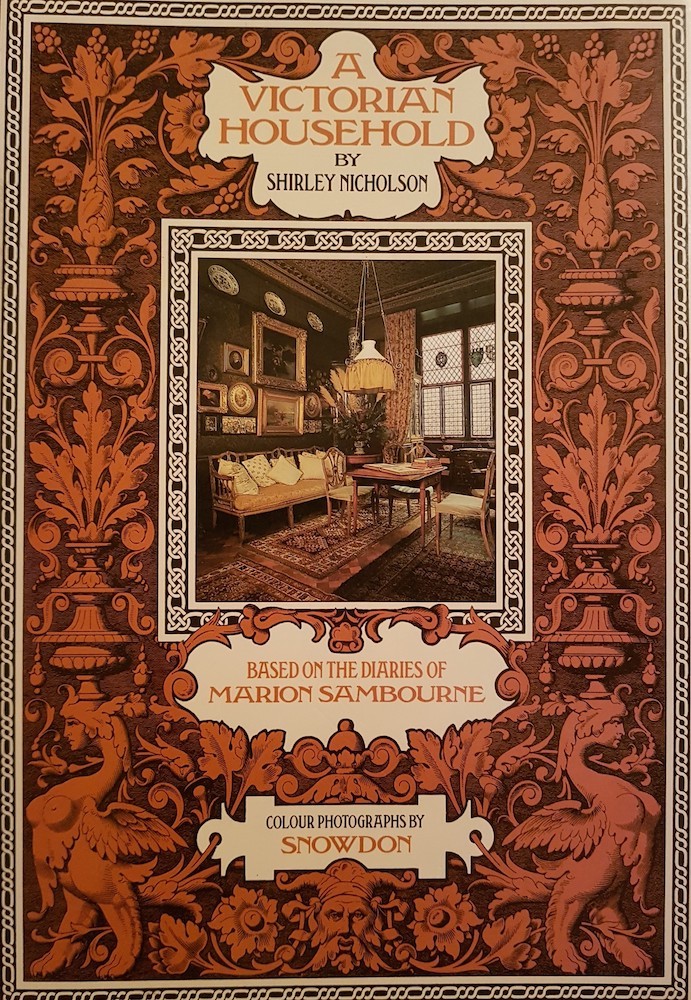

With or without a visit to 18 Stafford Terrace, however, anyone interested in the Victorian and Edwardian eras should read A Victorian Household, Shirley Nicholson’s absorbing account of life in and around the Sambourne home. Based on the daily journal kept by Marion Sambourne for over thirty years until her death on the eve of the First World War, the book offers an unparalleled insight into middle-class family existence that remains as compelling today as when it was first published in 1988. By giving priority to Marion’s record over the diary that her husband kept throughout the same period, A Victorian Household offers a female perspective on internal and external family relations that is fresh and authentic in equal measure. Backed up by the many letters that survive between Marion, Linley, their children, friends and relations, it is an extraordinary record of everyday life.

The story behind the book’s creation is an object lesson in the importance of preserving family archives. Shirley Nicholson was volunteering for the Victorian Society at Sambourne House in the early 1980s when she opened a chest of drawers on one of the top floors and found a stack of papers that had remained untouched since the property passed into public ownership. With permission to take the documents home so that she could decipher the handwriting at her leisure, Nicholson realised that she had discovered a treasure trove of primary source material for the reconstruction of a lost world. In the process of transcribing the diaries and reading through the letters, Nicholson developed a deep affinity with her subjects, and it shows. Whenever the author paraphrases the characters or intervenes in her own voice, there is never any doubt that the feelings expressed are the correct ones.

The Sambournes were a middle-class family, and the book’s chief appeal lies in the rich detail it provides of such a family’s quotidian existence. We learn about the meals they took, Marion’s relations with cook and housemaids ‘below stairs’, the social visiting that formed such an important part of a Victorian lady’s daily round, their shopping, theatre trips and holidays, the parents’ perennial worries over their talented daughter and hapless son. We encounter the regular bouts of ‘seediness’ that afflicted women and men of a certain class (Marion often stays in bed until late morning) and the anxiety caused by serious illness throughout the immediate and wider family. The portrayal of female life is intimate without being invasive, and there are equally fascinating descriptions of the male world as illuminated through Linley Sambourne’s career as one of the most celebrated cartoonists of the day.

In addition to the immediacy of Marion Sambourne’s voice and the fluency of Nicholson’s prose, the book is illustrated with photographs and drawings from the family archive that bring the characters visually to life. The original hardback edition is further distinguished by colour photographs from inside 18 Stafford Terrace taken by Antony Armstrong-Jones, First Earl of Snowdon, whose grandmother Maud Messel was Marion and Linley’s daughter; subsequent paperback versions allowed Nicholson to revise the text in a number of places, but hardback copies are well worth hunting down for the splendour of the interior views. While the flow of the book’s narrative is not interrupted by footnotes, Nicholson’s transcriptions of Marion’s diaries and those of her husband Linley are freely available to consult online (see below), so the reader is able to chase up references for themselves. A Victorian Household quickly established itself as a source book for social historians, but it remains first and foremost a wonderful read.

Links to the Diaries

- (offsite) Diaries of Marion Sambourne

- (offsite) Diaries of Linley Sambourne

Bibliography

Nicholson, Shirley. A Victorian Household: Based on the Diaries of Marion Sambourne. London: Barrie & Jenkins, 1988.

Created 1 June 2023