he tradition of wall decoration dates back to Egyptian and Roman wall paintings, and the early Chinese produced sheets of rice paper painted with birds, flowers and landscapes. During the Medieval Ages painted patterns on walls and canvas as well as woven tapestries adorned the interior of churches and castles (Gloag 53). Thus wallpaper began as a cheap substitute for this rich tapestry and paneling, as a less expensive alternative to the wall-hangings of the wealthy. The first wallpapers were decorations made for wood panels, printed by wood blocks and then colored in by hand. Though called wallpaper, the paper was not attached directly to the wall until the 1800s. Instead, it was pasted onto linen and the linen was then attached to the walls. Wallpaper's popularity increased in Elizabethan England and throughout Europe, a fascination began with these fine papers that offered protection against dampness and an improved ability to handle fireplace smoke (Krasner-Khait). Along with these practical reasons, wallpaper provided a decorative element that could reflect different materials and enhance the room's interior.

he tradition of wall decoration dates back to Egyptian and Roman wall paintings, and the early Chinese produced sheets of rice paper painted with birds, flowers and landscapes. During the Medieval Ages painted patterns on walls and canvas as well as woven tapestries adorned the interior of churches and castles (Gloag 53). Thus wallpaper began as a cheap substitute for this rich tapestry and paneling, as a less expensive alternative to the wall-hangings of the wealthy. The first wallpapers were decorations made for wood panels, printed by wood blocks and then colored in by hand. Though called wallpaper, the paper was not attached directly to the wall until the 1800s. Instead, it was pasted onto linen and the linen was then attached to the walls. Wallpaper's popularity increased in Elizabethan England and throughout Europe, a fascination began with these fine papers that offered protection against dampness and an improved ability to handle fireplace smoke (Krasner-Khait). Along with these practical reasons, wallpaper provided a decorative element that could reflect different materials and enhance the room's interior.

The use of wallpaper became so widespread that in 1712, England introduced a tax on paper that was "painted, printed or stained to serve as hangings." The industry continued to grow in spite of this and the development of a printing machine in 1839 that allowed for the printing of endless lengths of paper led to an expansion from 1,000,000 pieces in 1834 to 19,000,000 pieces in 1861 (Bridgeman 301). The Manchester Exhibitions of 1849 also contributed to their popularity, which led to the inclusion of an entire wallpaper section at Great Exhibition of 1851, showcasing an overwhelming variety of designs. Wallpaper was now applied directly to plaster walls and by the beginning of the 1800s, dividing the wall into three parts — the dado, filler and frieze — became fashionable. Often borders differentiated each section, which bore distinctive yet interrelated patterns (Leopold 18). During the Victoran era, wallpapers fell into two classes: simple and complicated. The simple typically depicted a repeated geometric pattern printed from a single wood block. The complicated consisted of more complex designs, including shields, vases or flowers and were created from several blocks (Krasner-Khait). Many were designed to appear three-dimensional, using trompe l'oeil technique made popular in France. Despite the significant advances in technology during this era, interior designers consistently looked to the past for inspiration.

In the early Victorian age, ornate furniture, swaths of fabric and various knicknacks cluttered every available surface in the typical middle-class drawing room. Wallpaper design featured standard imitations of costly fabrics, drapery, architectural moldings and cornices and often gave the impression of marble or wood grained surfaces. Borders resembling a tasseled braid or a swag of fabric were often added, and imitations of embossed leather or damask with exotic names like Lignomur, Anaglypta and Calcorian became common (Cooper). This sort of decoration displayed new-found cultural interests, prosperity and status and followed the fashionable notion that a bare room revealed poor taste. The critics of high Victorian style, known as the Aesthetic Movement, objected not only to the style and quality of machine-made decorations but also to the manner in which they were used in the home (Burrows). Reacting to the excess and over-embellishment, designers such as William Morris and Owen Jones, author of The Grammar of Ornament (1856), worked to restore "good taste" and re-establish quality workmanship. Following principles introduced by the PRB, Morris insisted on the purest colors and techniques and his influence is evident in the hundreds of mass-produced papers manufactured from the 1880s until the end of the century (Krasner-Khait). The basic principles of this reform in design were characterized by flat and conventionalized or more abstract patterns, instead of the naturalistic or rounded trompe l'oeil designs in relief. Designers often drew inspiration from nature and plant life, resulting in patterns such as Trellis (1864), Pomegranate (1864), and Sparrows & Bamboo (1872). Color schemes included lighter and brighter shades, contrasting the traditional idea that deep, rich and dark colors enhanced the importance of a room.

Some of the prominent designers of wallpaper during the Aesthetic and Decadent movements included Lindsay Butterfield, who designed floral motif wallpaper for Liberty & Co; Walter Crane, a founding member of the Art Workers Guild and designer for Jeffrey & Co.; Christopher Dresser, whose abstract designs made him one of the more futuristic designers; E.W. Godwin, a pioneer of the Anglo-Japanese style; Owen Jones, who systematized ornament and emphasized stylized forms in The Grammar of Ornament; William Morris, a leader of the Arts & Crafts movement whose designs combined stylized natural elements with geometric structure; Augustus Welby Pugin, who produced Gothic revival inspired designs; and Charles Francis Annesley Voysey, whose crisp lines and hallmark "Voysey-birds" characterized his wallpaper designs (Burrows).

Discussion Questions

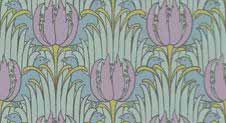

1. Here are two examples of wallpaper designs during this period:

Source: Left: www.adelphipaperhangings.com. Right: Voysey, Bird and Tuliup, from www.achome.co.uk. Click on picture for larger image.

What are the major differences in the two designs? Which one characterizes high Victorian style and which one represents the Aesthetic Movement? How so?

2. According to late Victorian writers, the highest style of decorating was not measured by the quantity of patterns employed, but by the discreet layering of wallpaper, paint, furnishing textiles and carpet to create a harmonious ensemble. No single element was to be considered alone; interior decorating did not exist solely of wallpaper, or carpet, or fabric, instead the emphasis lay in the overall artistic unity of design (Burrows). During this time the architect and designer Baillie Scott presented the idea of wallpaper no longer acting as a mere backdrop but as a decorative device (Cooper 12). How did this change in the role of wallpaper come about? How does this reflect the change in decoration of the Victorian interior?

3. In 1881's "Some Hints on Pattern Designing," Morris writes:

Doubtless there will be some, in these days at least, who will say, 'Tis most helpful to me to let the bare walls alone.' So also there would be some who, when asked with what manner of books they will furnish their room, would answer, 'With none.' But I think you will agree with me in thinking that both these sets of people would be in an unhealthy state of mind, and probably of body also; in which case we need not trouble ourselves about their whims, since it is with healthy & sane people only that art has dealings (Burrows).

To contrast this, a contemporary English interior designer, Aldam Heaton, writes in 1897:

It is quite possible that a plain, or nearly plain wall, with a dado and frieze, more or less ornamental, might have been far better than any sort of pattern. Our rooms often get terribly over-patterned - patterned wall and ceiling, patterned floor, patterned curtains, patterned furniture-covers; where are we to get a little rest for the eye if not occasionally by a plain wall? (Heaton, 108)

And in 1904, Norman Shaw wrote:

The present-day belief that good design consists of pattern — pattern repeated ad nauseum — is an outrage to good taste. A wallpaper should be a background pure and simple — that, and nothing else. The art teaching of today follows in the steps of William Morris, a great man who somehow delighted in glaring wallpapers. The kind of paper-hanging that we need most of all is what I may describe, for want of a better word, as the 'tone' wall-paper (Cooper 12).

How does Morris' comment reflect his idea on the role and significance of art in daily life? How do the comments of Heaton and Shaw reflect this idea?

4. In The Grammar of Ornament, Owen Jones gathered together examples from ancient civilizations and modern times and drew them according to his principles of flat pattern. He intended the included designs to illustrate design history and act as inspiration; however, the result was literal copying of the plates by textile and wallpaper manufacturers. Often the case with Victorian design, elements were appropriated from different cultures and past eras. What does this say about the Victorians? How does this process reflect their culture?

5. Towards the end of his life, Morris remarked how he had spent his life "ministering to the swinish luxury of the rich" (Hapgood 54). While his wallpapers, as well as those of other Aesthetes, offered an element of hand crafted design and quality workmanship, the poor could not afford this luxury of "good taste." His wallpapers were, however, supported by the moderate middle classes. How does the production and consumption of wallpaper, as well as other decorative arts reflect class distinctions? Which classes are able to support the ideals of the Aesthetes and Decadents? How does this conflict with Morris' political ideals?

Related Materials

Works Cited

Bridgeman, Harriet and Drury, Elizabeth, ed. The Encyclopedia of Victoriana. New York : Macmillan, 1975.

Burrows, J. R. http://www.burrows.com/index.html.

Cooper, Nicholas. The Opulent Eye : Late Victorian and Edwardian Taste in Interior Design. London : Architectural Press, 1977.

Gloag, John. Victorian Taste; Some Social Aspects of Architecture and Industrial Design, from 1820-1900. New York : Barnes & Noble Books, 1973.

Hapgood, Marilyn Oliver. Wallpaper and the Artist. New York: Abbeville Press, 1992.

Heaton, Aldam. Beauty and Art. New York: D. Appleton, 1897.

Krasner-Khait, Barbara. "Wallpaper," www.history-magazine.com. October/November 2001.

Leopold, Allison Kyle. Victorian Splendor: Re-creating America's 19th century Interiors. New York: Stewart, Tabori & Chang, 1986.

Last modified 22 November 2004