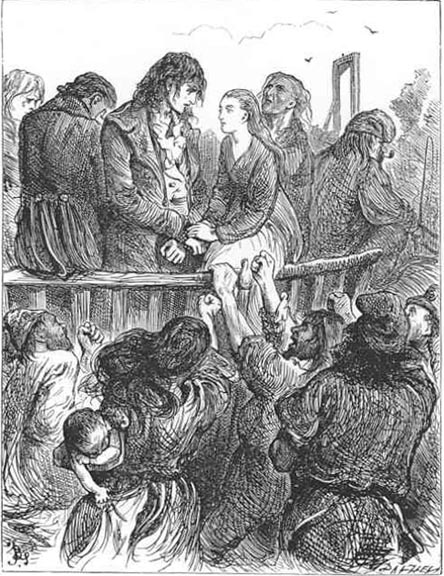

The Third Tumbrel

Fred Barnard

1874

13.7 x 10.5 cm (5 ⅜ by 4 ⅛ inches)

Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities (Household Edition), p. 173.

Sydney Carton's assuming the identity of Charles Darnay in order to save Lucie, her husband, and child requires that he allow himself to be transported to the Guillotine in one of the many tumbrels expropriated by the revolutionary leaders. By coincidence, he shares his final moments with another blameless victim of anti-aristocratic hysteria. [Continued below.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite it in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated: Carton's Last Romantic Gesture

Of the riders in the tumbrils, some observe these things, and all things on their last roadside, with an impassive stare; others, with a lingering interest in the ways of life and men. Some, seated with drooping heads, are sunk in silent despair; again, there are some so heedful of their looks that they cast upon the multitude such glances as they have seen in theatres, and in pictures. Several close their eyes, and think, or try to get their straying thoughts together. Only one, and he a miserable creature, of a crazed aspect, is so shattered and made drunk by horror, that he sings, and tries to dance. Not one of the whole number appeals by look or gesture, to the pity of the people.

There is a guard of sundry horsemen riding abreast of the tumbrils, and faces are often turned up to some of them, and they are asked some question. It would seem to be always the same question, for, it is always followed by a press of people towards the third cart. The horsemen abreast of that cart, frequently point out one man in it with their swords. The leading curiosity is, to know which is he; he stands at the back of the tumbril with his head bent down, to converse with a mere girl who sits on the side of the cart, and holds his hand. He has no curiosity or care for the scene about him, and always speaks to the girl. Here and there in the long street of St. Honore, cries are raised against him. If they move him at all, it is only to a quiet smile, as he shakes his hair a little more loosely about his face. He cannot easily touch his face, his arms being bound.

On the steps of a church, awaiting the coming-up of the tumbrils, stands the Spy and prison-sheep. He looks into the first of them: not there. He looks into the second: not there. He already asks himself, “Has he sacrificed me?” when his face clears, as he looks into the third.

“Which is Evrémonde?” says a man behind him.

“That. At the back there.”

“With his hand in the girl’s?”

“Yes.”

The man cries, “Down, Evrémonde! To the Guillotine all aristocrats! Down, Evrémonde!”

“Hush, hush!” the Spy entreats him, timidly.

“And why not, citizen?”

“He is going to pay the forfeit: it will be paid in five minutes more. Let him be at peace.” [Book Three, “The Track of a Storm,” Chapter XV, “The Footsteps Die out Forever,” pp. 174-175]

Commentary: “It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done. . . .”

In Book the Third, “The Track of a Storm,” Chapter XV, “The Footsteps Die out Forever,” Carton, disguised as the last representative of the infamous Evrémondes, calmly, tenderly takes the hand of the little seamstress whom he met in Chapter XIII. His gesture is intended to give her courage, even as the blood-thirsty mob of "patriots" surrounding the cart vilifies them, and The Vengeance scrutinises him. But Barnard does not include the terrible woman, the spy, the robed ministers of Sainte Guillotine, or legion of knitting-women. Barnard focuses on Carton's tranquil reassurance of his timid companion rather than on the machinations of the substitution plot. The precise moment would seem to be this:

The supposed Evrémonde descends, and the seamstress is lifted out next after him. He has not relinquished the patient hand in getting out, but holds it as he promised. . . . “Keep your eyes upon me, dear child, and mind no other object.” (175)

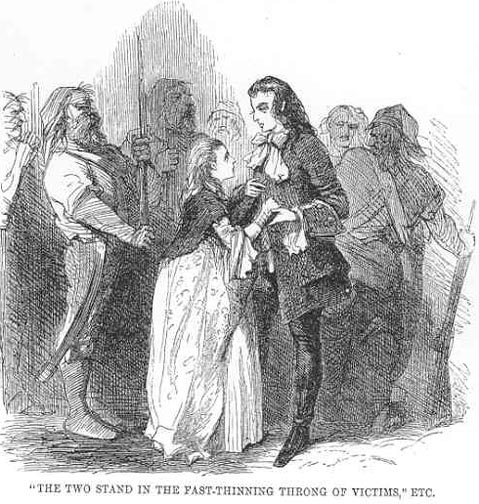

John McLenan, the American illustrator for the Harper's serialisation of the novel, also focuses on the courage and tenderness of Carton in his final moments in the final Harper's Weekly instalment's The Two Stand in the Fast-thinning Throng of Victims," etc., 26 November 1859. In the American serial illustration, Carton and the seamstress have already alighted from the cart, and stand on the ground, guarded by heavily armed Jacobins. The moment in both Barnard and McLenan is something of an anti-climax since Miss Pross has already thwarted Madame Defarge's plans in Like the soul of the furious woman whose body lay lifeless on the ground in the McLenan sequence, and in "You might, from your appearance, be the wife of Lucifer . . ." (169) in Barnard's.

Relevant Illustrations from Other Editions: 1859, 1867, and 1910

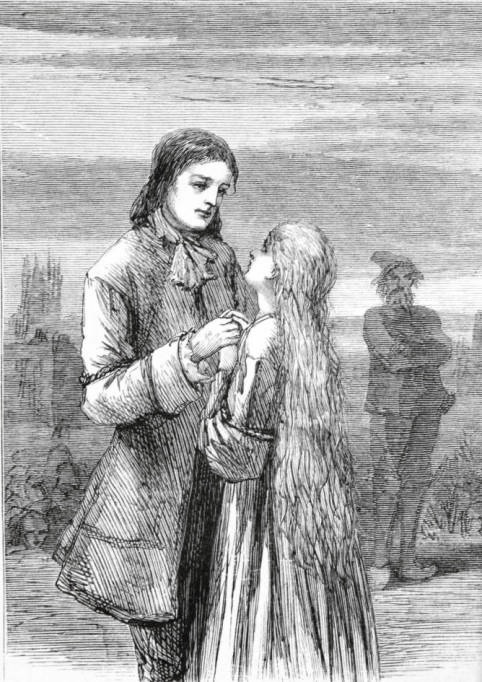

Left: McLenan's 3 December 1859 depiction of Carton's comforting the little seamstress on the scaffold, The two stand in the fast-thinning throng of victims. Right: A slightly later American interpretation of the intimarte scene on the scaffold, Sol Eytinge, Junior's sentimental dual portrait which serves as the frontispiece for the Diamond Edition, Sydney Carton and the Seamstress (Vol. XIII, 1867).

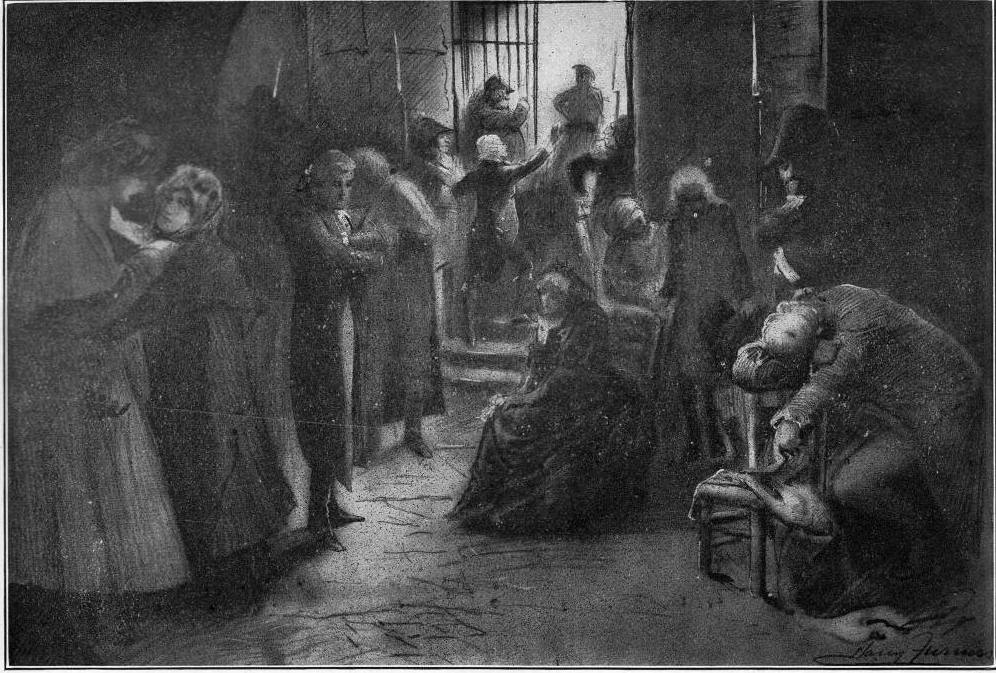

Above: Harry Furniss's atmospheric dark plate of the scene inside the prison in the Charles Dickens Library Edition, Book Three, Chapter Thirteen, Sydney Carton and the Little Seamstress (1910).

Bibliography

Allingham, Philip V. "'Charles Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities (1859) Illustrated: A Critical Reassessment of Hablot Knight Browne's Accompanying Plates." Dickens Studies Annual. 33 (2003): pp. 109-158.

Cooper, Fox. The Tale of Two Cities; or, The Incarcerated Victim of The Bastille. An Historical Drama, in a Prologue and Four Acts. London: John Dicks, 1860. Dicks' Standard Plays, No. 780. Rpt. Dickens Dramatized Series of Plays. Theatre Arts Press. Acheson, AB: Amazon.ca, 2015.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by John McLenan. Harper's Weekly. (26 November 1859): 765.

Dickens, Charles. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). London: Chapman and Hall, November 1859.

Dickens, Charles. A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. 14 vols. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867. Vol. XIII.

Dickens, Charles. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1874. Vol. VIII.

_____. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London: Collins, 1905.

_____. A Tale of Two Cities, American Notes, and Pictures from Italy. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. Vol. XIII.

Hammerton, J. A. The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Edition of the Works of Charles Dickens. London: Educational Book, 1910.

Maxwell, Richard, ed. "Appendix I: "On The Illustrations." Charles Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities. London: Penguin, 2003. Pp. 391-396.

Sanders, Andrew. "Introduction" to Charles Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Vann, J. Don. "A Tale of Two Cities in All the Year Round, 30 April-26 November 1859." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: Modern Language Association, 1985. Pp.71-72.

Woodcock, George. "Introduction" to Charles Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1970.

Victorian

Web

Illustration

Fred

Barnard

A Tale

of Two Cities

Charles

Dickens

Created 21 February 2011

Last modified 23 January 2026