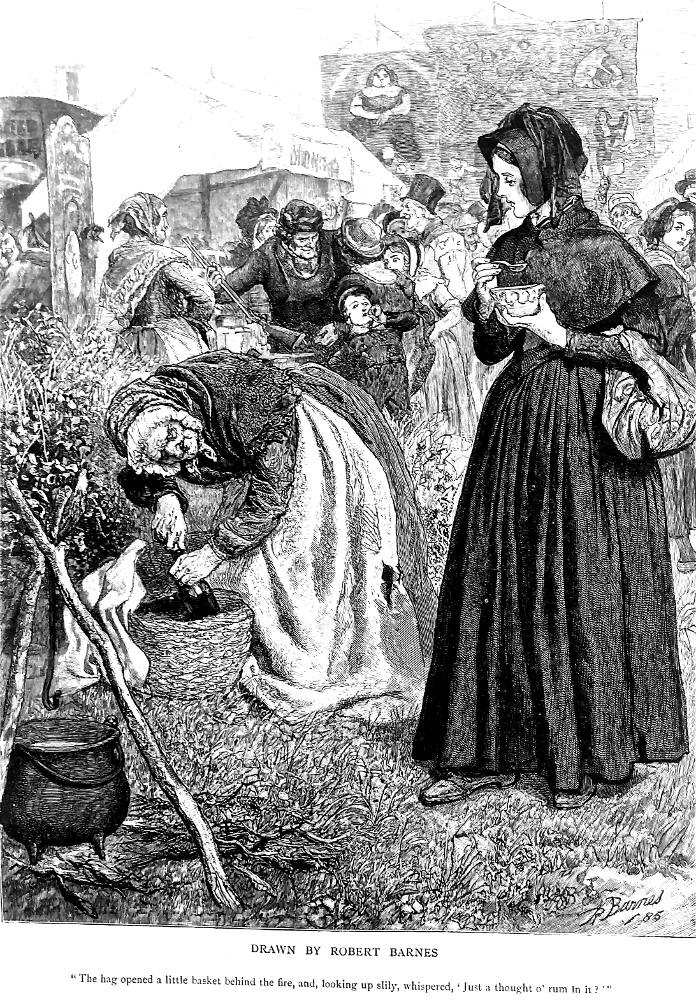

The hag opened a little basket behind the fire, and, looking up slyly, whispered, "Just a thought 'o run in it?"

Robert Barnes

9 January 1886 (Part Two)

Composite Woodblock Engraving

22.9 cm high by 17.2 cm wide — 8 ¾ by 6 ⅝ inches

Thomas Hardys's The Mayor of Casterbridge, Chapter III, p. 41.

[Click on image to enlarge it.]

See below for passage illustrated and commentary.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.