Living in a Palace of Art: artifice, the toilette, and hairdressing

Unlike the Romantics, who praise Nature and the natural, the Decadents look upon external and human nature as fallen, and on this point they agree with traditional Christian thought since the Middle Ages and before. But these artists and poets of the late nineteenth century do not, like Christian believers, look up to God and a higher spiritual realm. Finding themselves submerged in their ennui, nostalgia, and sense of incompleteness, they look upon extreme artifice — to the anti-natural — as their only hope. Poems and illustrations therefore abound with images of jewels and instances of extreme artifice, such as masks, Byzantine goldwork, and cosmetics, and particularly ornate, perverse, or unnatural examples of natural phenonena, such as orchids and peacocks.

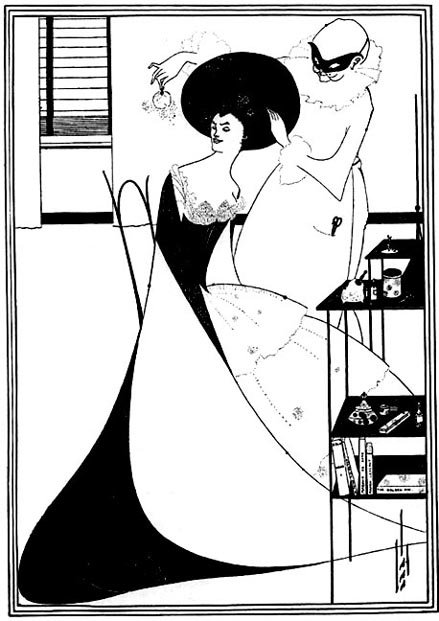

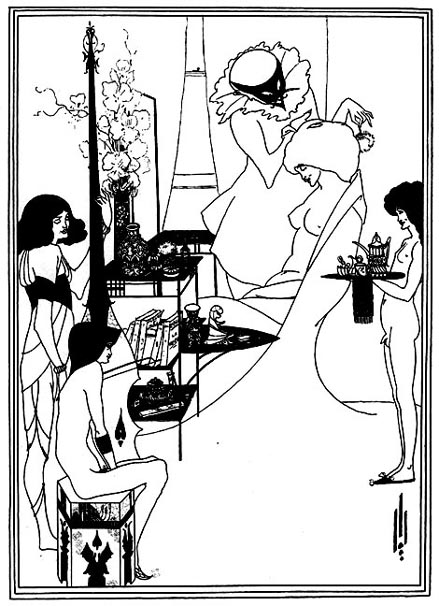

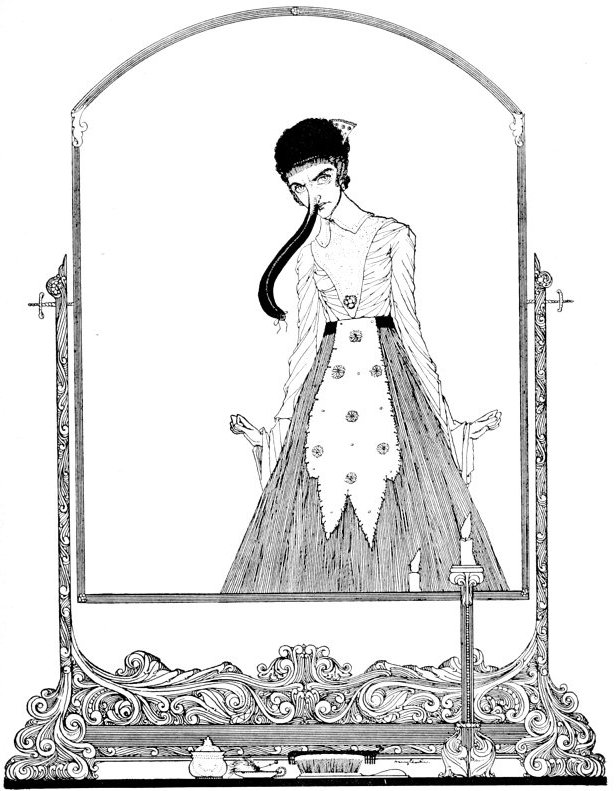

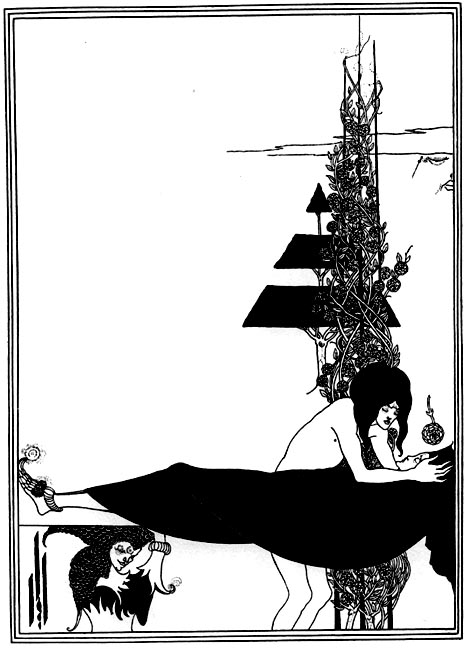

oOher characteristic subjects (and images) related to cosmetics and other examples of artifice are the male dandy and the woman who creates an artificially heightened beauty at dressing tables in their boudoir. Beardsley, author of “The Ballad of a Barber,” creates such a scene in both versions of his Toilette of Salome and in The Coiffing":

Three by Beardsley — Left to right: (a) Published version of Toilette of Salome and (b) the first, explicitly erotic version. (c) Beardsley's illustration for “The Ballad of a Barber,” a poem in which the hairdresser's frustration at failing to tame a young girl's hair leads him to murder her — the artist and his subject dying for his art: The Coiffing [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

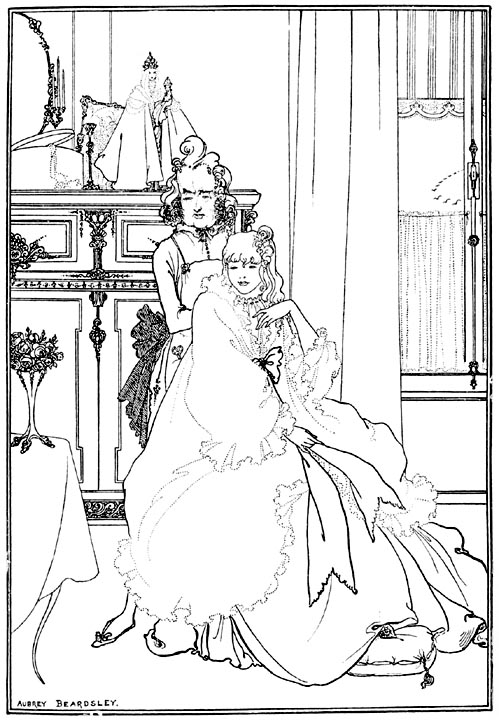

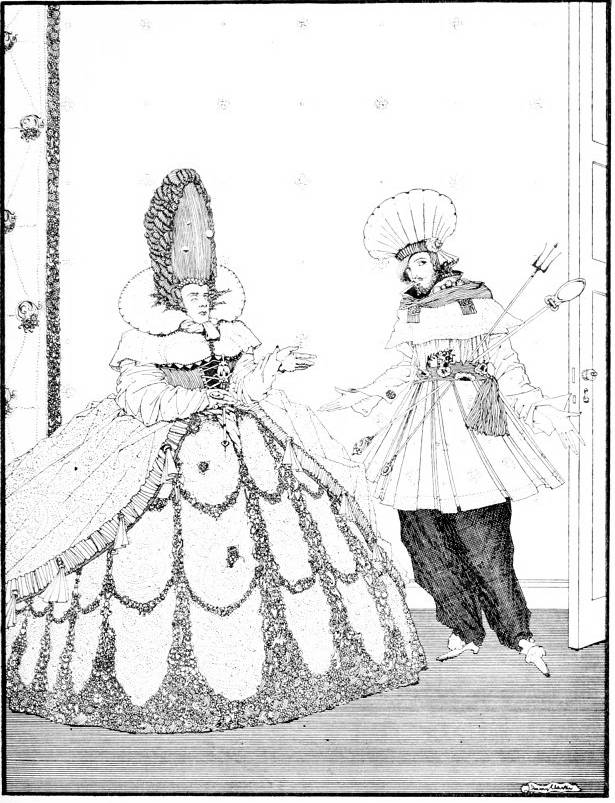

Clarke follows his master not only in his representations of elaborate wigs, such as we find in his illustrations to Perrault's version of “Sleeping beauty,” and “Cinderella” but also in Anyone but Cinderella would have dressed their heads awry:

Left to right: (a) What, is not the key of my closet among the rest?. (b) “I will have it so,” replied the queen, “and will eat her with a sauce Robert”. (c) Anyone but Cinderella would have dressed their heads awry [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

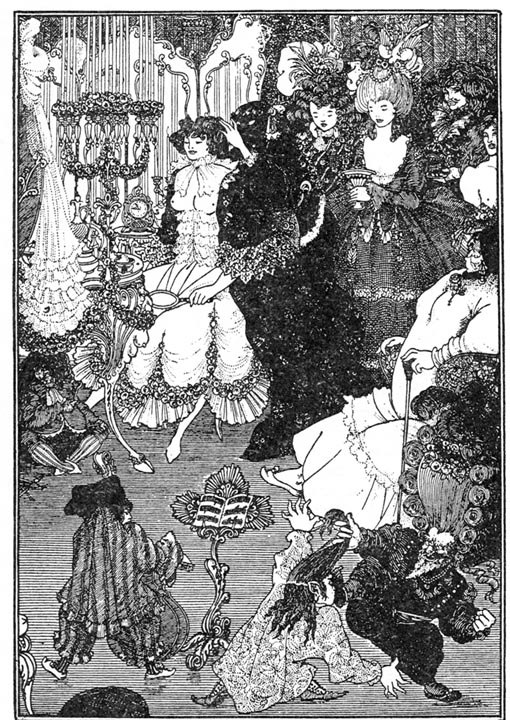

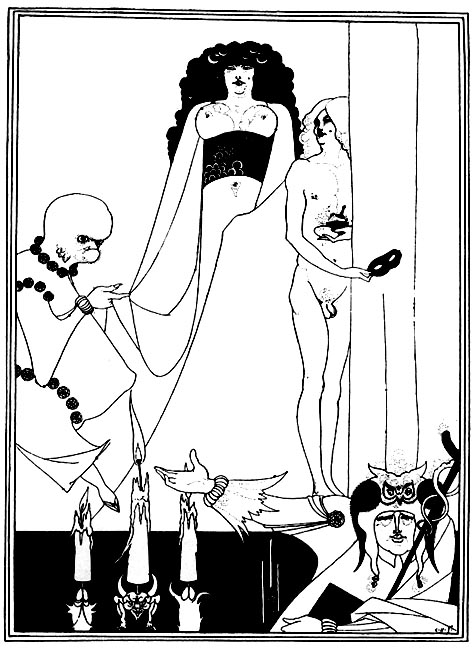

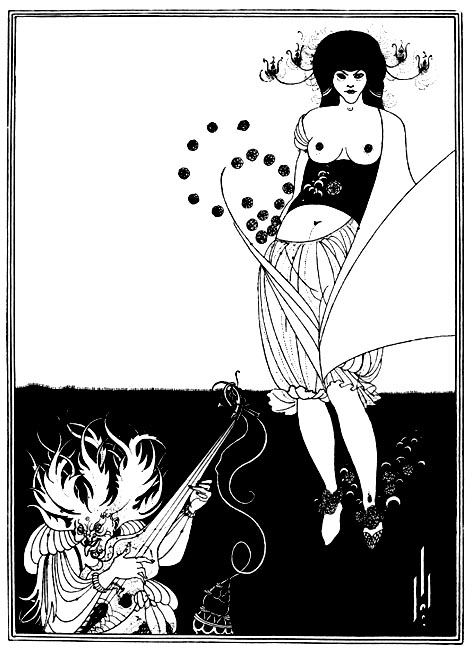

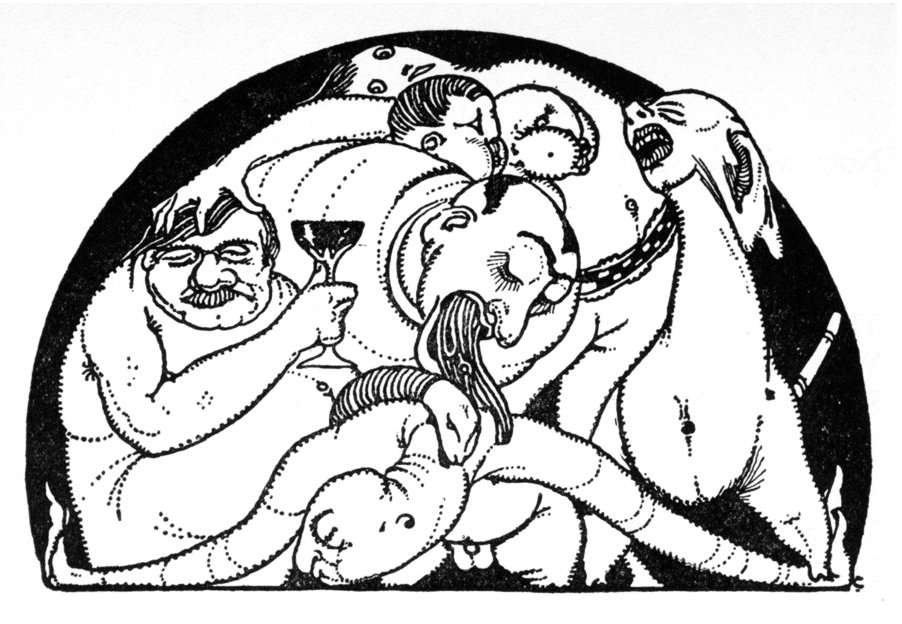

The decadent's characteristic attempts to escape the human condition by means of posing, artifice, and evil, all of which are conceived of as unnatural and therefore better than nature, also leads to visual and verbal art that emphazises the grotesque images found in many works by both illustrators, such as the figures in the foreground of Venus at her toilet, the musician in The Stomach Dance, and the figure at the left and lower right in Enter Herodias.

Left to right: (a) Venus at her toilet and (b) Enter Herodias. (c) The Stomach Dance [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

Clarke, who uses many grotesques in his page decorations for his illustrated Faust — see gallery — also uses them in his images for fairy tales.

Sex and death

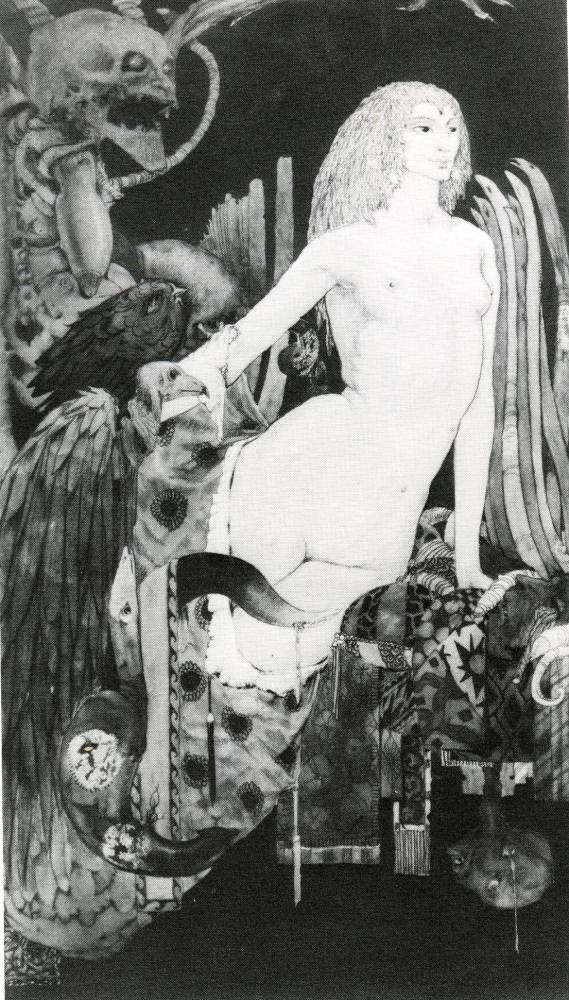

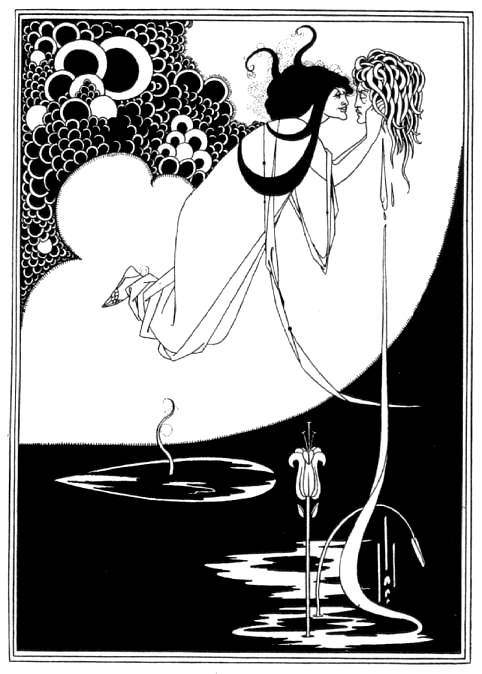

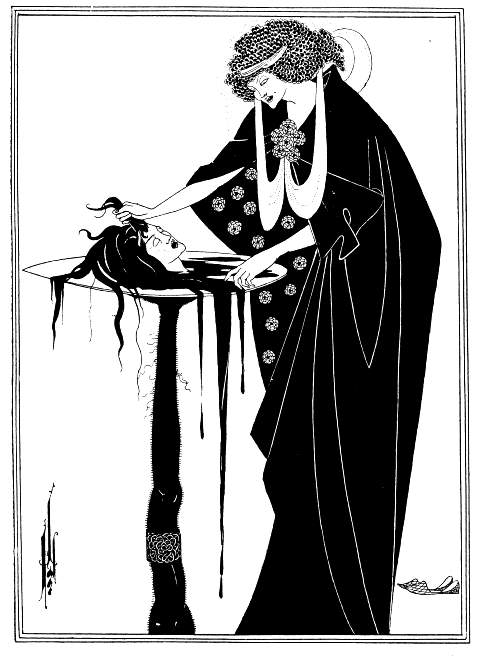

This love of the grotesque appears in these artists' depictions of sexuality, particularly in their connection of sex and death, such as Clarke's illustration for for Swinburne's “Faustine,” which juxtaposes a female nude, skull, and vulture and Beardsley's The Platonic Lament and The Climax for Wilde's Salome:

Left to right: (a) Clarke's Faustine and (b) Beardsley's The Platonic Lament. (c) Beardsley's The Climax [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

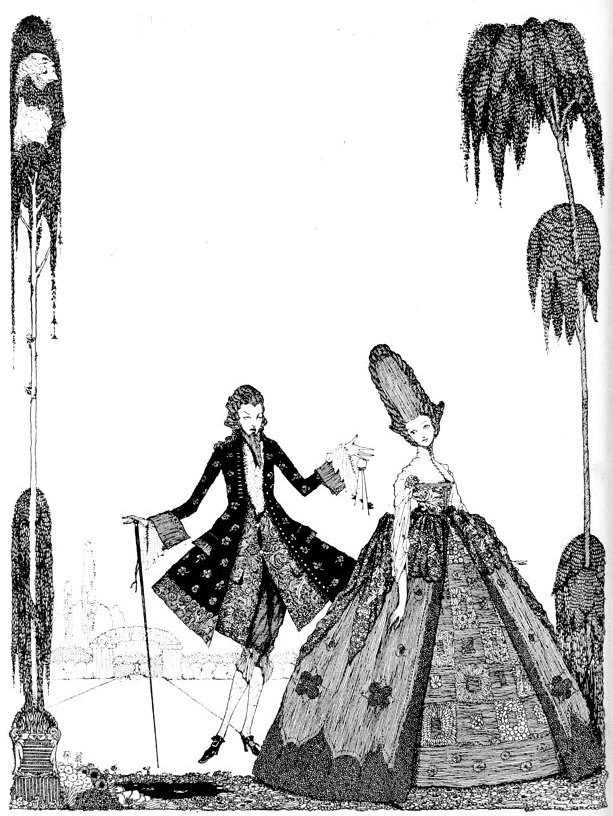

Although Beardsley occasionally creates an image of heterosexual male desire, as in Belinda in Bed (from The Rape of the Lock), which depicts a bare-breasted young woman, many of his works include androgynous figures created by eo emphasizing the Pre-Raphaelite Fair Lady's thick neck and strong chin to the point that some of his women look male, as, for instance, does Salome in The Dancer's Reward while John the Baptist appears very feminine (The two Salomes in this image and in The Stomach Dance seem entirely different people.) Clarke fittingly creates an androgyne as a page decoration for his illustrated edition of the poems of Swinburne, the poet of androgyny, and in some of his images for Perrault's Fairy Tales he creates androgynous figures. Thus, in The prince enquires of the aged countryman, only his sword reassures readers that the printing house hasn't made a mistake: his outer garment looks much like a gown, and the feathers and decorations on his hat plus his profile make him easily confused with a woman.

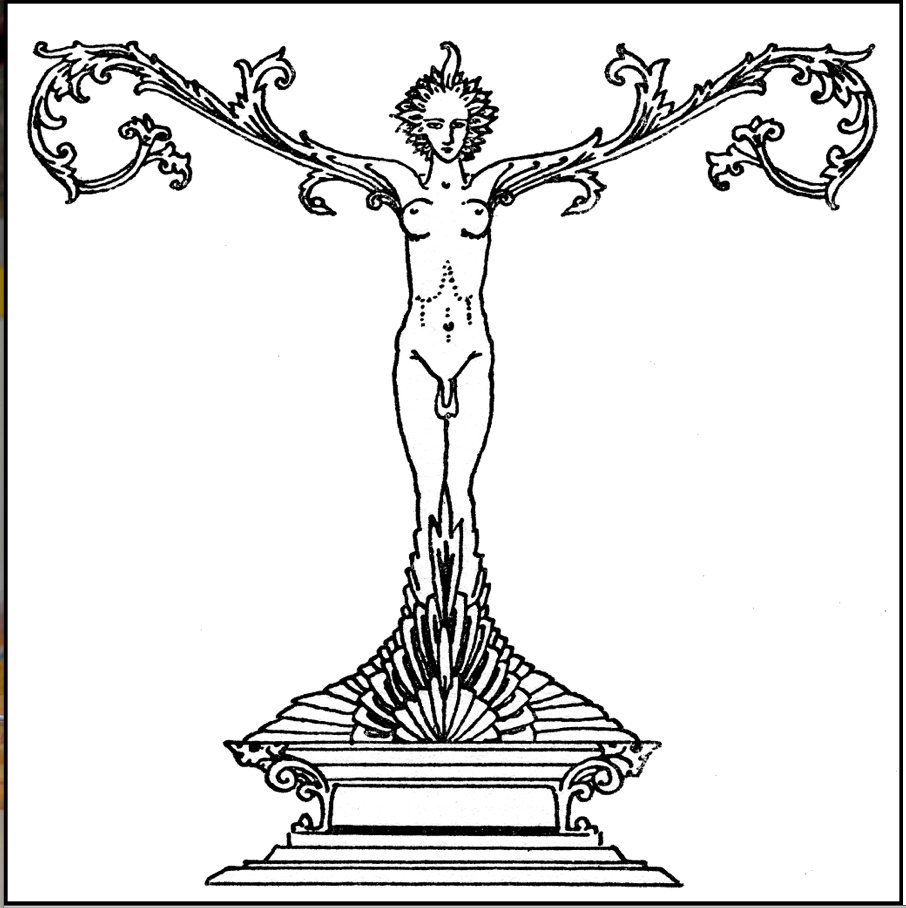

Left to right: (a) Beardsley's The Dancer's Reward. (b) Beardsley's The Stomach Dance. (c) Clarke's page decoration for Swinburne's Selected Poems [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

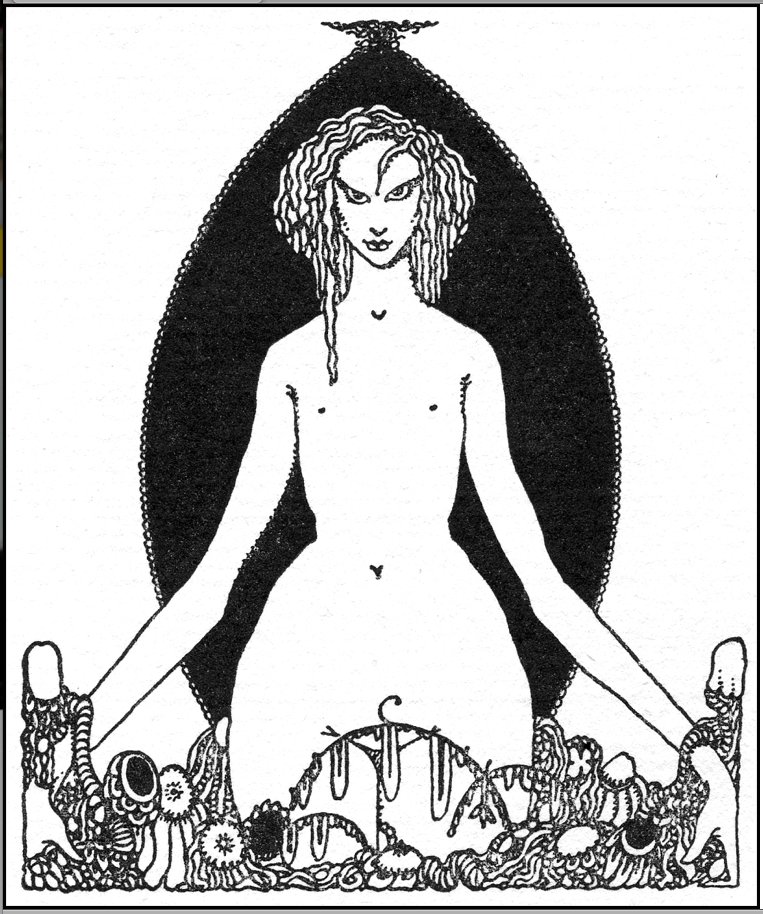

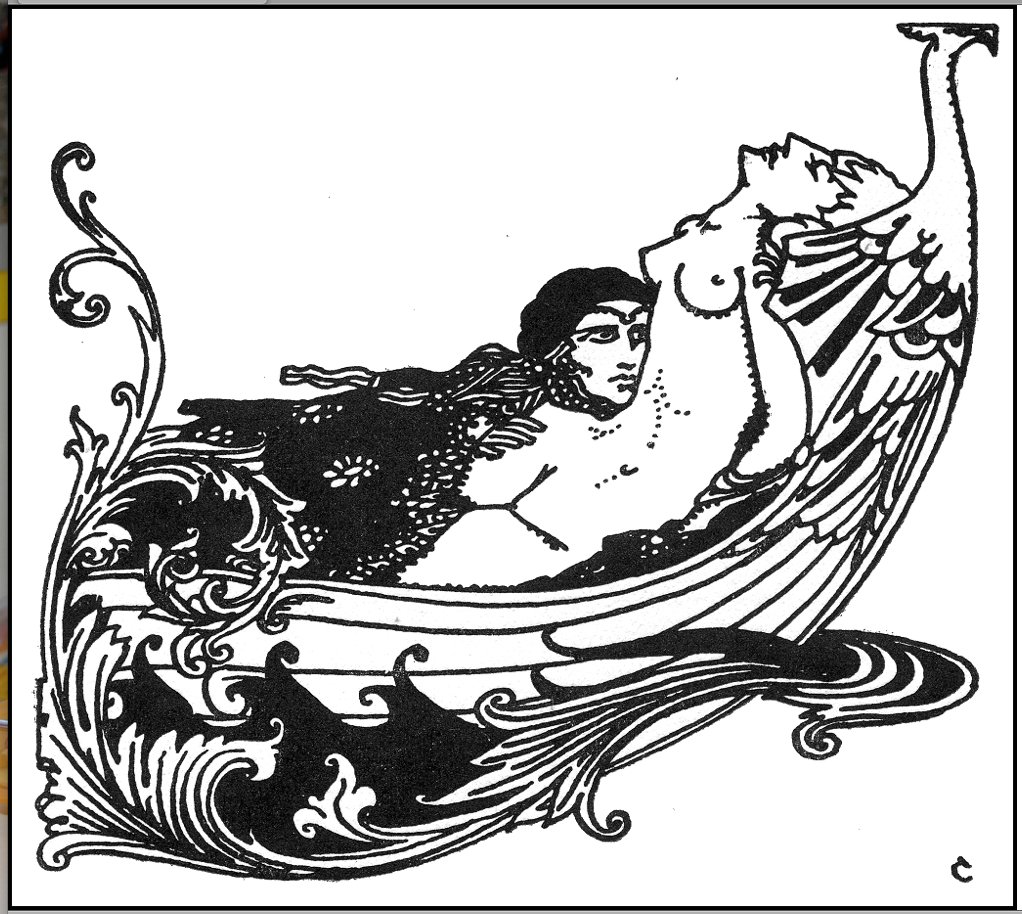

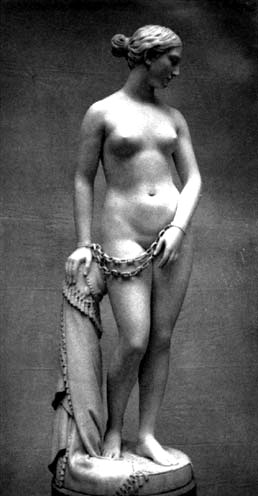

Even when he draws obviously female figures, Clarke emphasizes perversity. The wide-hipped woman below appears naked, not nude, as she stares out at the viewer, and the page decoration showing a clothed man and nude woman in a boat has him leaning his face against against her side immediately beneath her breasts as he grasps her thigh. Clarke's draws the woman's arms behind her as she throws her head back. Is she unconscious, or is she in the throes of passion? Is she a bound captive who is being assaulted? Nineteenth-century art occasionally represents nude women in chains but does not include a male figure unless, like Perseus or St. George, he has arrived as a rescuer.

(a) and (b) Clarke's decorations for Swinburne's Selected Poems. (c) S. Nicolson Babb's The Victim and (d) Hiram Powers' The Greek Slave

Related Material

Last modified 26 December 2012