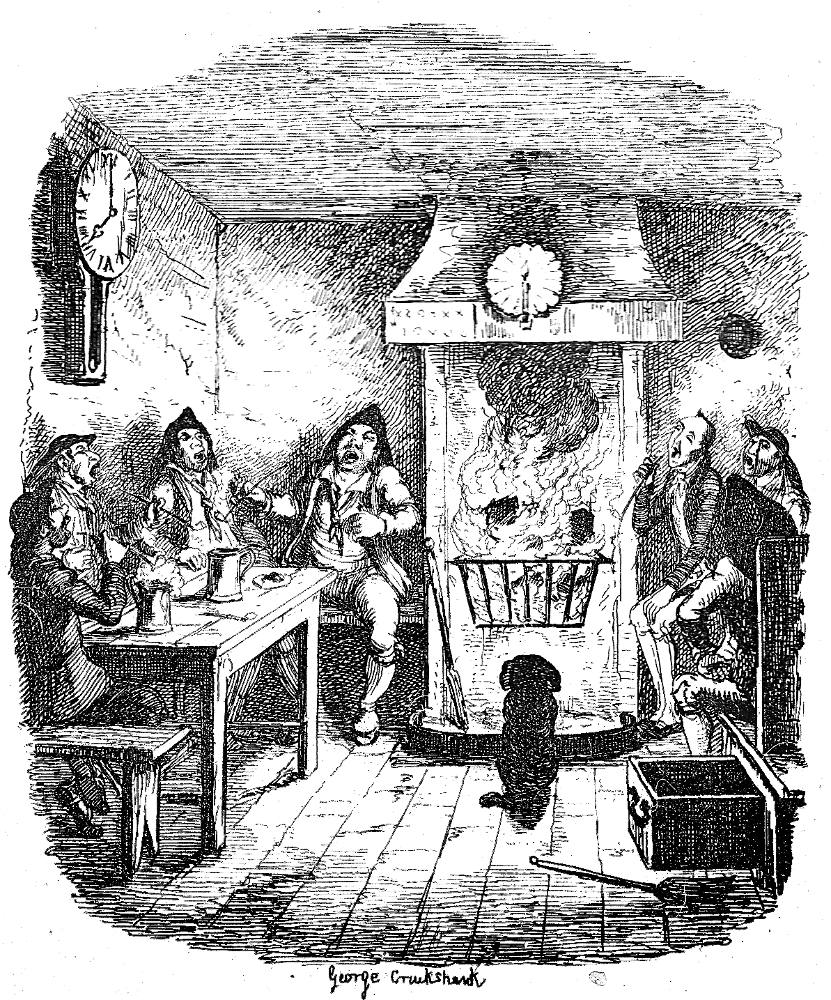

Scotland Yard (half-page vignette) by George Cruikshank. Copper-engraving (1836): 8.5 cm high by 8.3 cm wide (3 ⅜ by 3 ⅛ inches), vignetted, facing p. 67. Steel-engraving (1839): 11.5 cm high by 9.7 cm wide (4 ½ by 3 ¾ inches), vignetted, facing p. 47. In re-engraving the 1836 copper-plate Cruikshank decided to define the two figures to the right more sharply — and to enlarge the comfortable dog. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Passage Illustrated: Drinking and smoking into the evening

Scotland-yard is a small — a very small-tract of land, bounded on one side by the river Thames, on the other by the gardens of Northumberland House: abutting at one end on the bottom of Northumberland-street, at the other on the back of Whitehall-place. When this territory was first accidentally discovered by a country gentleman who lost his way in the Strand, some years ago, the original settlers were found to be a tailor, a publican, two eating-house keepers, and a fruit-pie maker; and it was also found to contain a race of strong and bulky men, who repaired to the wharfs in Scotland-yard regularly every morning, about five or six o'clock, to fill heavy waggons with coal, with which they proceeded to distant places up the country, and supplied the inhabitants with fuel. When they had emptied their waggons, they again returned for a fresh supply; and this trade was continued throughout the year. [Pp. 47-48 in the 1839 edition; pp. 65-66 in the 1836 edition]

But the choicest spot in all Scotland-yard was the old public-house in the corner. Here, in a dark wainscoted-room of ancient appearance, cheered by the glow of a mighty fire, and decorated with an enormous clock, whereof the face was white, and the figures black, sat the lusty coalheavers, quaffing large draughts of Barclay's best, and puffing forth volumes of smoke, which wreathed heavily above their heads, and involved the room in a thick dark cloud. From this apartment might their voices be heard on a winter's night, penetrating to the very bank of the river, as they shouted out some sturdy chorus, or roared forth the burden of a popular song; dwelling upon the last few words with a strength and length of emphasis which made the very roof tremble above them.

Here, too, would they tell old legends of what the Thames was in ancient times, when the Patent Shot Manufactory wasn't built, and Waterloo-bridge had never been thought of; and then they would shake their heads with portentous looks, to the deep edification of the rising generation of heavers, who crowded round them, and wondered where all this would end; whereat the tailor would take his pipe solemnly from his mouth, and say, how that he hoped it might end well, but he very much doubted whether it would or not, and couldn’t rightly tell what to make of it — a mysterious expression of opinion, delivered with a semi-prophetic air, which never failed to elicit the fullest concurrence of the assembled company; and so they would go on drinking and wondering till ten o'clock came, and with it the tailor's wife to fetch him home, when the little party broke up, to meet again in the same room, and say and do precisely the same things, on the following evening at the same hour. ["Scenes," Chapter 4, "Scotland Yard," p. 48 in the 1839 edition; pp. 67-68 in the 1836 edition]

Commentary: Nothing Whatsoever Like a Police Station

In this sketch of London characters and settings, first published in The Morning Chronicle under the pseudonym "Boz" on 4 October 1836 (and therefore it did not appear until Macrone's "Second Series" in 1837), Dickens offers no hint initially that this industrial quarter adjacent to the river, formerly the site of the Scottish Embassy (closed in 1604 after the creation of the United Kingdom under King James the First), is about to become famous as the headquarters of the London Metropolitan Police, founded by Home Secretary Sir Robert Peele in 1829. The new force had its headquarters at 4 Whitehall Place, which had a rear entrance on a street called Great Scotland Yard. The prosaic, modern building that today's Londoners know as "New Scotland Yard," located in Lower Thames Street on the Victoria Embankment (even closer to the river), replaced the old embassy building when the force moved from Great Scotland Yard in 1890. However, the branch of the force involving constables on horseback has its stables at 7 Great Scotland Yard, across the street from the original headquarters.

At first glance, Cruikshank may be describing a sociable fireside in any cozy public house on a winter's evening — although closer inspection of the clientele reveals that they are wearing coal-heavers' headgear, a detail singularly lacking in Dickens's description one page after the reader has encountered the illustration. Although Cruikshank has omitted the dark wainscotting, the roaring coal-fire, sending clouds of black smoke up the capacious chimney, is indeed "mighty" and the clock above the heads of the drinkers (left) "enormous." In the absence of a focal character such as a publican in the sketch, Cruikshank has made the coal-fire itself the centre of the composition, suggestive of conviviality, in contrast to the winter chill without. The coal-grate (again not described in the text) is appropriately large, its warmth being enjoyed by a medium-sized dog of nameless breed (another detail added by Cruikshank). As in the text, the drinkers consume flagons of ale and puff on long-stemmed pipes as they join in some sort of rough chorus, if one may judge by their open mouths. The scene may also be regarded as something of a forerunner of that in another riverside watering-hole and working-class haunt, the bar of The Six Jolly Fellowship-Porters presided over by the stern Miss Potterson in Our Mutual Friend (June 1864), Chapter Six, "Cut Adrift." According to Michael Slater, when Dickens was just a boy and his father a prisoner in the Marshalsea Debtors' Prison, he wandered the streets of London "after his day's drudgery [in Warren's Blacking Factory, and] once sat down on a bench to watch the coal-heavers dancing" (81) in Scotland Yard. By the time that Dickens penned his sketch of the area, however, great changes wereafoot in Scotland Yard:

One of the eating-house keepers began to court public opinion, and to look for customers among a new class of people. He covered his little dining-tables with white cloths, and got a painter’s apprentice to inscribe something about hot joints from twelve to two, in one of the little panes of his shop-window. Improvement began to march with rapid strides to the very threshold of Scotland-yard. A new market sprung up at Hungerford, and the Police Commissioners established their office in Whitehall-place. The traffic in Scotland-yard increased; fresh Members were added to the House of Commons, the Metropolitan Representatives found it a near cut, and many other foot passengers followed their example. ["Scotland Yard," pp. 71-72 in the 1836 edition]

In a word,"gentrification" swept through the environs of Scotland Yard after the opening of New London Bridge in 1831 and the subsequent destruction of the former span.

Scanned image, image correction, formatting, and caption by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens: A Biography. London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1990.

Bentley, Nicholas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens: Index. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z. The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Chapter Five, "Scotland Yard." Sketches by Boz. Second series. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: John Macrone, 1836. Pp. 63-76.

Dickens, Charles. "Scotland Yard," Chapter 4 in "Scenes," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Chapman and Hall, 1839, rpt. 1890.

Dickens, Charles. "Scotland Yard," Chapter 4 in "Scenes," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1876. Vol. XIII.

Dickens, Charles. "Scotland Yard," Chapter 4 in "Scenes," Sketches by Boz Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-Day People. Ed. Thea Holme. The Oxford Illustrated Dickens. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1957; rpt., 1987. Pp. 18-24.

Hammerton, J. A. "The Story of this Book." Charles Dickens's Sketches by Boz Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-Day People. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 1. Pp. i-v.

Kitton, Frederic G. "George Cruikshank." Dickens and His Illustrators. London: Chapman & Hall, 1899. Pp. 1-28.

Long, William F., and Paul Schlicke. "Bung Against Spruggins: Reform in 'Our Parish.'" Dickens Quarterly 34, 1 (March 2017): 5-13.

Slater, Michael. Charles Dickens: A Life Defined by Writing. New Haven and London: Yale U. P., 2009.

Created 5 May 2017 last updated 17 May 2023