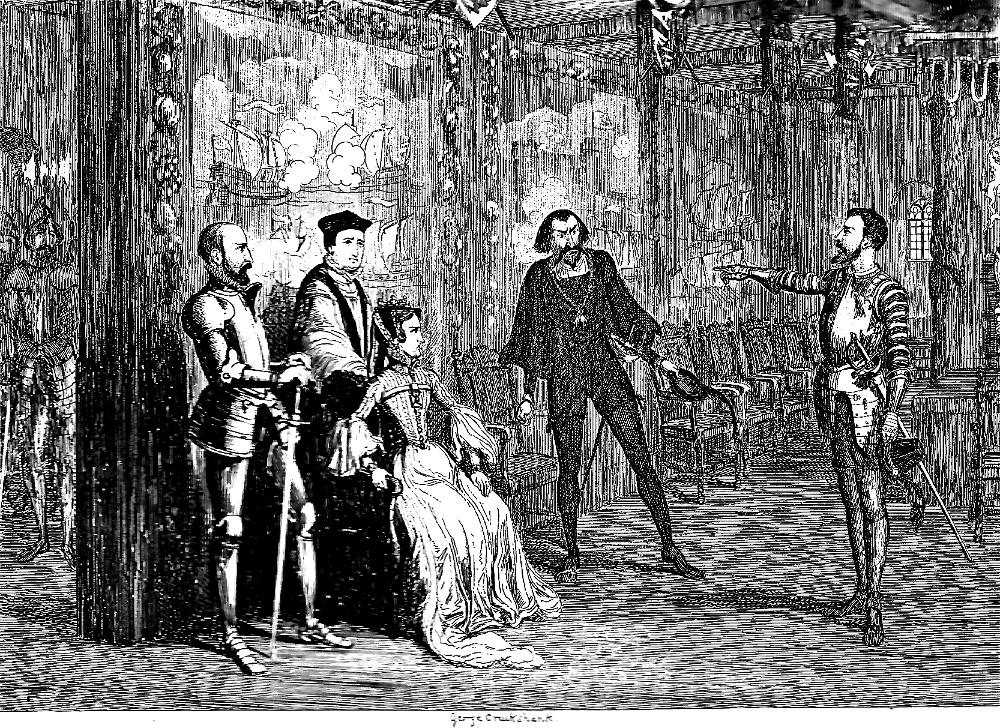

Sir Thomas Wyat dictating terms to Queen Mary in the Council. — George Cruikshank. Tenth instalment, October 1840 number. Seventieth illustration and and twenty-ninth steel-engraving in William Harrison Ainsworth's The Tower of London. A Historical Romance. Illustration for Book the Second, Chapter XXVIII. 10 cm high x 14.2 wide, framed, facing p. 306: running head, "Plans of the Insurrection." After grave deliberation, Mary resolves to hold parlay with the rebel-leader in order to understand his position. Sir Henry Bedingfeld, Lieutenant of the Tower, arranges the safe passage of Sir Thomas Wyat, who, contrary to the advice of the Duke of Suffolk and Lord Guilford Dudley, agrees. The scene is Mary's Council Chamber in the Lieutenant's Lodgings rather than the White Tower, if one may judge by the abundant wood-panelling. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated

Ushered into the council-chamber, Wyat found Mary seated on a chair of state placed at the head of a row of chairs near a partition dividing the vast apartment, and covered with arras representing various naval engagements. The wooden pillars supporting the roof were decorated with panoplies; and through an opening on the right of the queen, Wyat perceived a band of armed men, with their leader at their head, cased in steel, and holding a drawn sword in his hand. Noticing these formidable preparations with some uneasiness, he glanced inquiringly at Bedingfeld.

"Fear nothing," observed the old knight. "My head shall answer for yours."

Thus re-assured, Wyat advanced more confidently towards the queen, and when within a few paces of her, paused and drew himself up to his full height. Bedingfeld took up a station on the right of the royal chair, and supported himself on his huge two-handed sword. On the left stood Gardiner and Renard.

"I have sent for you, traitor and rebel that you are," commenced Mary, "to know why you have thus incited my subjects to take up arms against me?”

“I am neither traitor nor rebel, madam,” replied Wyat, “as I have already declared to one of your council, and I but represent the mass of your subjects, who being averse to your union with the prince of Spain, since you refuse to listen to their prayers, are determined to make themselves heard."

"Ha! God's death! sir," cried Mary, furiously, "do you, or do any of my subjects think they can dispose of me in marriage as they think proper? But this is an idle pretext. Your real object is the subversion of my government, and my dethronement. You desire to place the princess Elizabeth on the throne — and in default of her, the Lady Jane Grey."

"I desire to uphold your majesty's authority," replied Wyat, "provided you will comply with my demands."

"Demands!"cried Mary, stamping her foot, while her eyes flashed fire. "It is the first time such a term has been used to me, and it shall be the last. In God's name, what are your demands? Speak, man."

"These, madam," replied Wyat, firmly. "I demand the custody of the Tower, — the care of your royal person, — the dismissal of your council, — and the head of your false counsellor, Simon Renard."

"Will nothing less content you?" inquired Mary, sarcastically.

"Nothing," returned Wyat.

"I pray your majesty to allow me to punish the insolence of this daring traitor," cried Renard, in extremity of fury.

"Peace, sir," rejoined Mary, majestically. "Now hear me in turn, thou traitor Wyat. No man ever dictated terms to my father, and, by his memory! none shall do so to me. At once, and peremptorily, I reject your conditions; and had not Sir Henry Bedingfeld pledged his word for your safety, my guards should have led you from hence to the scaffold. Quit my presence, and as I would rather be merciful than severe, and spare the lives of my subjects than destroy them, if you disperse your host, and submit yourself to my mercy, I will grant you a free pardon. Otherwise, nothing shall save you."

“When we next meet your majesty may alter your tone," rejoined Wyat; "I take my leave of your highness.”

So saying, he bowed and retired with Sir Henry Bedingfeld. [Chapter XXVIII. — Of the Queen's Speech in the Council-Chamber; and her Interview with Sir Thomas Wyat," p. 307-308]

Commentary

Having met Sir Thomas Wyat briefly in conference with the French ambassador in the text, we encounter him now in the Cruikshank historical canvas as an intrepid leader, a loyal Englishman who has paradoxically rebelled against the Queen and Council because he is opposed to the "Spanish Match." The setting is not the royal apartments of Queen Anne Boleyn, who was kept under house arrest in a palace on the south lawn, near the present-day raven cages. Originally, the Queen's Apartments were occupied by Queen Katherine of Aragon, but the buildings fell into disrepair and were razed. The term "The Queen's House" came into currency in the latter part of the reign of Queen Victoria, as it served as Her Majesty's official residence whenever she visited the Tower; Queen Elizabeth II continues this tradition. The Queen's House has been the residence for some other queens — Lady Jane Grey and the Lady Arabella Stuart, and possibly the Princess Elizabeth.

Jane, comfortably housed in the Tower of London, was supportive of Mary's claim to the throne once Catholic forces in the Council had overthrown Northumberland. Mary was adamant that she would not execute her kinswoman, but her attitude towards Jane changed when Jane's father, the Duke of Suffolk, joined Wyat's rebellion at Rochester Castle in Kent, a county which Protestant preachers had much influenced. On 29 January 1554, the army over which Mary had given command to the Duke of Norfolk to put down Wyat's Kentish forces deserted in large numbers, forcing Norfolk to retreat. When Mary learned of Wyat's successes in Kent, she issued a pardon to his followers if they were to return to their homes within twenty-four hours. However, Wyat still commanded a force of some four thousand, which reached Southwark on 3 February. There they found their way blocked by Mary's supporters, who had occupied London Bridge. Wyatt discretely withdrew when Sir John Brydgesthreatened to fire on the suburb with the guns of the Tower.The rebel army then marched up the south bank to Kingston-on-Thames, where they repaired the bridge that Mary's supporters had attempted todestroy, and crossed the river. Wyat's forces met little resistance as they marched through the outskirts of London, until the inhabitants of Ludgate repelled them. Wyat's rebellion effectively ended when the rebel army broke up.

However, this is not the plot-line that the novelist presents, for Ainsworth is not merely recounting or dramatizing history; rather, he is romanticizing it, sensationalizing the period of 1553-54. In point of fact, for example, although Wyat's forces infested the suburbs south of the Thames, they were never able to launch a concerted assault on the Tower of London. But, since an account of strategic withdrawals on either side is not the stuff of romance, Ainsworth must have felt compelled to offer exciting battle scenes worthy of the pageant of Tudor history that he has promised in the preface, and that Cruikshank has realised with gusto: Attack upon the Brass Mount by Lord Guildford Dudley, Attack upon St. Thomas's Tower by the Duke of Suffolk, and Sir Thomas Wyat attacking the By Ward Tower in Chapter XXIX. "Desirous of exhibiting the Tower in its triple light of a palace, a prison, and a fortress" ("Preface," p. iv), Ainsworth must furnish a narrative that shows the Tower of London functioning in all three ways.

The social dynamics of the Council Chamber scene are apparent in Cruikshank's disposition of the principals. To the right, pointing to Renard (whose head he is demanding) is Wyat, a commanding soldier encased in armour and carrying a long rapier at his hip. Mary, seated as in the text, is neither peevish nor frustrated, but she receives Wyat's requests stone-faced. Cruikshank's stern faced, composed Mary calmly listens to Wyat's demands. There is no trace of uneasiness on Wyat's determined visage, although the illustrator has included two armed guards (hardly "a band") in the extreme left-hand margin, although they are not within Wyat's line of sight. Cruikshank's Mary neither flashes fire nor stamps her feet in impatience, or interrupt the handsome rebel. Behind her are counsellors suggestive of the temporal and religious orders that support her: the bald-headed, sober-sided Sir Henry Bedingfeld, Lieutenant of the Tower, also in full armour and holding a two-handed broad-sword; and Bishop Gardiner, Mary's chief political advisor. However, the black-clad foreigner, the olive-skinned, dark-haired, mustachioed Simon Renard, is furious that Mary is not having Wyat arrested; he will be doubly-vexed shortly when she refuses to permit Renard to pursue Wyat and arrest him, for she has given her word that the rebel leader may come and go freely. One cannot escape, however, the lowering effects of Cruikshank's tendency to caricature his villain, with the result that it is difficult to take the pasteboard Machiavel seriously.

Cruikshank makes the most of Ainsworth's stage directions with respect to the Council Chamber, which with its ornately carved wooden pillars is almost certainly not the chamber in the White Tower, but that in the Lieutenant's Lodgings. The tapestries which represent various naval engagements foreshadow England's dominion over the seas that the country will affirm when it defeats the Spanish Armada in 1588. Significantly, Cruikshank in the central panel, behind Renard, has depicted a mediaeval castle under naval bombardment, as if to imply the threat that Wyat's rebel forces now present the Tower of London, an impending conflict to which Wyat may be pointing.

Bibliography

"Ainsworth, William Harrison." http://biography.com

Ainsworth, William Harrison. The Tower of London. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Richard Bentley, 1840.

Burton, Anthony. "Cruikshank as an Illustrator of Fiction." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 92-128.

Carver, Stephen. Ainsworth and Friends: Essays on 19th Century Literature & The Gothic. 11 September 2017.

Department of Environment, Great Britain. The Tower of London. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1967, rpt. 1971.

Chesson, Wilfred Hugh. George Cruikshank. The Popular Library of Art. London: Duckworth, 1908.

Golden, Catherine J. "Ainsworth, William Harrison (1805-1882." Victorian Britain: An Encyclopedia, ed. Sally Mitchell. New York and London: Garland, 1988. Page 14.

Kelly, Patrick. "William Harrison Ainsworth." Dictionary of Literary Biography, Vol. 21, "Victorian Novelists Before 1885," ed. Ira Bruce Nadel and William E. Fredeman. Detroit: Gale Research, 1983. Pp. 3-9.

McLean, Ruari. George Cruikshank: His Life and Work as a Book Illustrator. English Masters of Black-and-White. London: Art and Technics, 1948.

Pitkin Pictorials. Prisoners in the Tower. Caterham & Crawley: Garrod and Lofthouse International, 1972.

Sutherland, John. "The Tower of London" in The Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 19893. P. 633.

Steig, Michael. "George Cruikshank and the Grotesque: A Psychodynamic Approach." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 189-212.

Vogler, Richard A. Graphic Works of George Cruikshank. Dover Pictorial Archive Series. New York: Dover, 1979.

Worth, George J. William Harrison Ainsworth. New York: Twayne, 1972.

Vann, J. Don. "The Tower of London, thirteen parts in twelve monthly instalments, January-December 1840." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: MLA, 1985. Pp. 19-20.

Last modified 22 October 2017