ossetti was a perfectionist who tried to create imposing illustrations of the highest aesthetic standards. To a large extent this aim was realized through a process of careful preparation, with each of his designs on wood being the product of numerous sketches and studies in which he experimented with various visual solutions until he was satisfied with the result. This, however, was not the end of the process. The intermediary stage of engraving meant that many variables were generated: the final drawing submitted by the artist was subject to interpretation by the engraver, who had to convert the artist’s work into a relief block, and the printed image was affected by many uncertainties such as the viscosity and quality of the ink, and even the permeability of the paper.

In short, perfect drawings did not always produce the most perfect proofs, and Rossetti was unwilling to accept any ‘faults,’ as he saw them, in the mediation of his work. As I have noted elsewhere, he was often antagonized by what he believed to be incompetent engraving, especially in work done by the Dalziels, and constantly fretted over even the smallest errors that no-one but himself would notice in the published illustrations. This attitude reflected his lack of understanding of the process, and on at least one occasion – in the preparation of The Maids of Elfen-Mere for William Allingham’s The Music Master (1855) – he sent in a drawing in chalk and wash which almost defied ‘the stern realities’ of engraving in lines on boxwood (Dalziel 86).

Inevitably, the engravings did not always match up to the artist’s expectations, and to reassert control he always wrote detailed corrections on the proofs, which he also marked with white paint and arrows to mark the areas in need of revision. The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, UK., contains four corrected (or ‘progress’) prints cut by the Dalziels, for ‘The Palace of Art’ from Tennyson’s famous ‘Moxon’ edition (1857): one for the illustration of St Cecilia and three for Arthur in the Vale of Avalon. Rossetti’s annotations are crammed into a very limited space and sometimes difficult to read; the following are transcripts which preserve the original grammar. Analysis of these texts provide a vivid insight into Rossetti’s aesthetic aims and ways of achieving those aims.

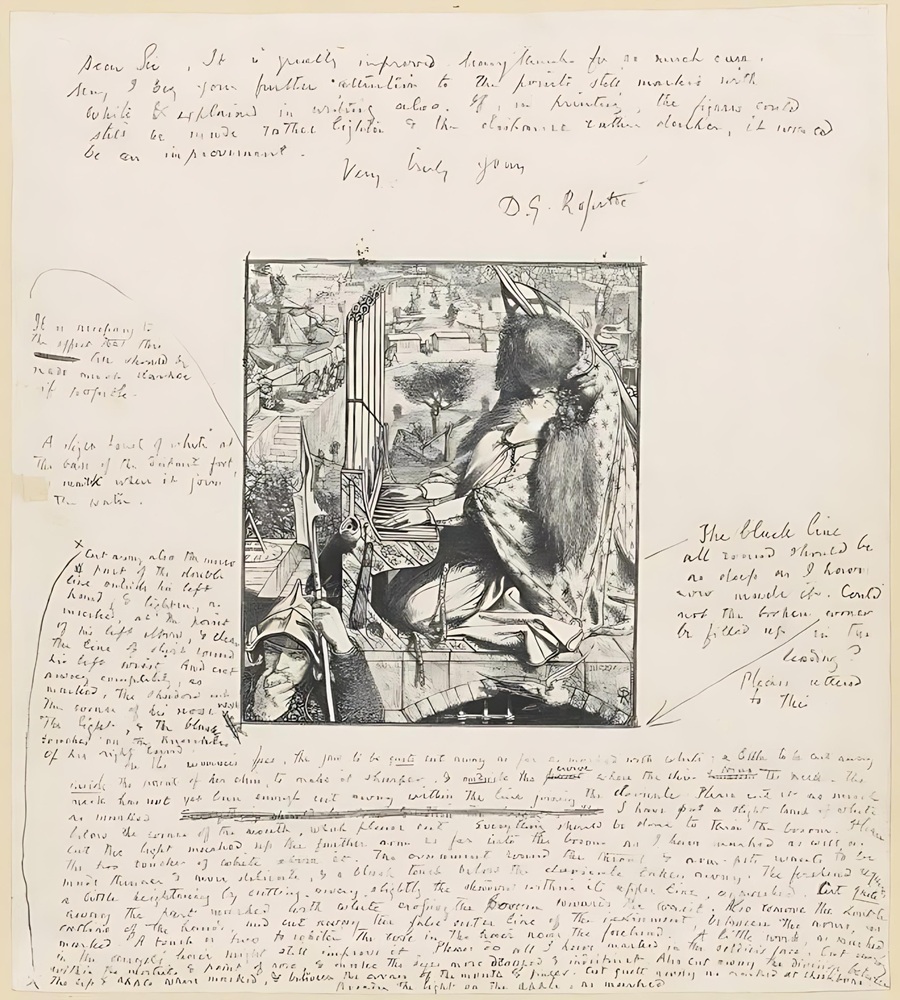

Proof for St Cecilia

The extensive annotations on this proof are Rossetti’s most comprehensive response to one of his engraved designs. There may have been others, now lost, and the artist’s comment that the current proof is ‘greatly improved’ indicates that others preceded it – perhaps with the same type of detailed instructions as the present one.

This is a corrected proof for first illustration for Tennyson’s ‘The Palace of Art,’ representing the encounter between St Cecilia and the angel.

Dear Sir, it is greatly improved. Many thanks for so much care. May I beg your further attention to the points still marked with white & explained in writing also. If, in printing, the figures could still be made rather lighter & the distance rather darker, it would be an improvement.

Very truly yours, D. G. Rossetti

It is necessary to the effect that this tree should be made much darker if possible.

A slight touch of white at the base of the distant fort, mark where it joins the water.

Cut away also the inner part of the double line outside his left hand, & lighten, as marked at the point of his left elbow, & clear the line of shirt around his left wrist. And cut away completely, as marked, the shadow at the corner of his nose next the light, & then black touches on the knuckles of his right hand.

In the woman’s face, the jaw to be quite cut away as far as marked with white; a little to be cut away inside the point of her chin, to make it sharper & outside the curve where the chin joins the neck. The neck has not yet been enough cut away within the line joining the clavicle. Please cut it is as much as marked [line crossed out]. I have put a light touch of white below the corner of the mouth, which please cut. Everything should be done to miss the bosom. Please cut the light marked up to the further arm as far into the bosom as I have marked as well as the two touches of white above it. The ornament around the throat and armpits wants to be made thinner & more delicate, & a black touch below the clavicle taken away. The forehead [illegible] a little heightening by cutting away slightly the shadow within its upper line, as marked. Cut quite away the part marked with white defining [?] the bosom towards the waist. Also remove the double outline of the hands, and cut away the false outline of the instrument between the arms, as marked. A touch or two to whiten the rose in the hair near the forehead. A little work, as marked, in the angel’s hair might still improve it. Please do all I have marked in the soldier’s face. Cut away within the nostril & point of nose, & makes the eyes more drooped & indistinct. Also cut away the division between the lips and apple where marked, & between the corners of the mouth & fingers. Cut quite away as marked at cheekbone.

Broaden the light on the apple, as marked.

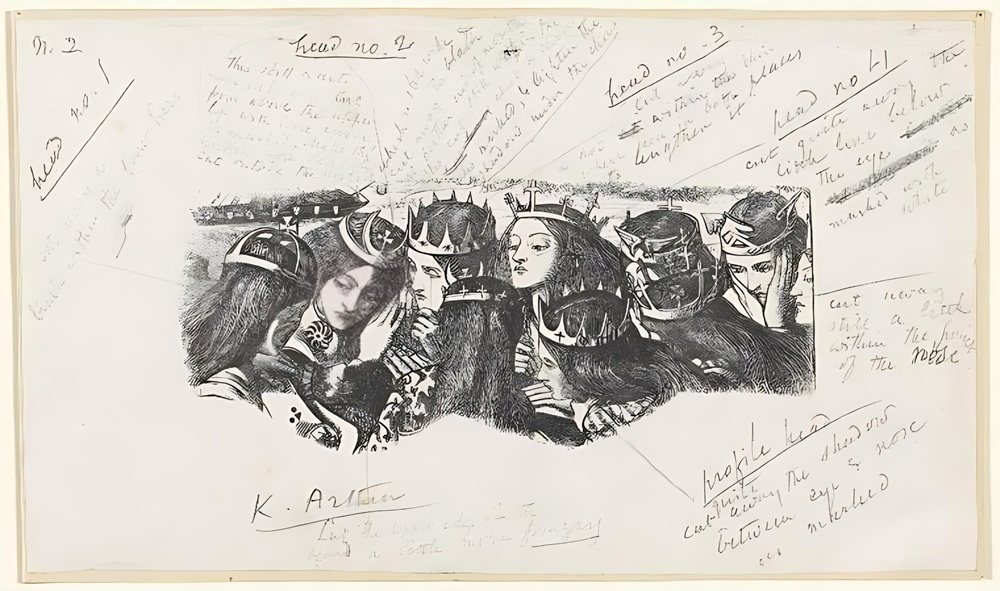

Proofs for King Arthur in the Vale of Avalon

This work in progress is divided into three separate proofs. The first two show the same section, the upper part of the print, in different ‘states.’ The other part would have been engraved on another block; these were then bolted together to create the completed impression. The third proof is the assembled image.

Proof 1

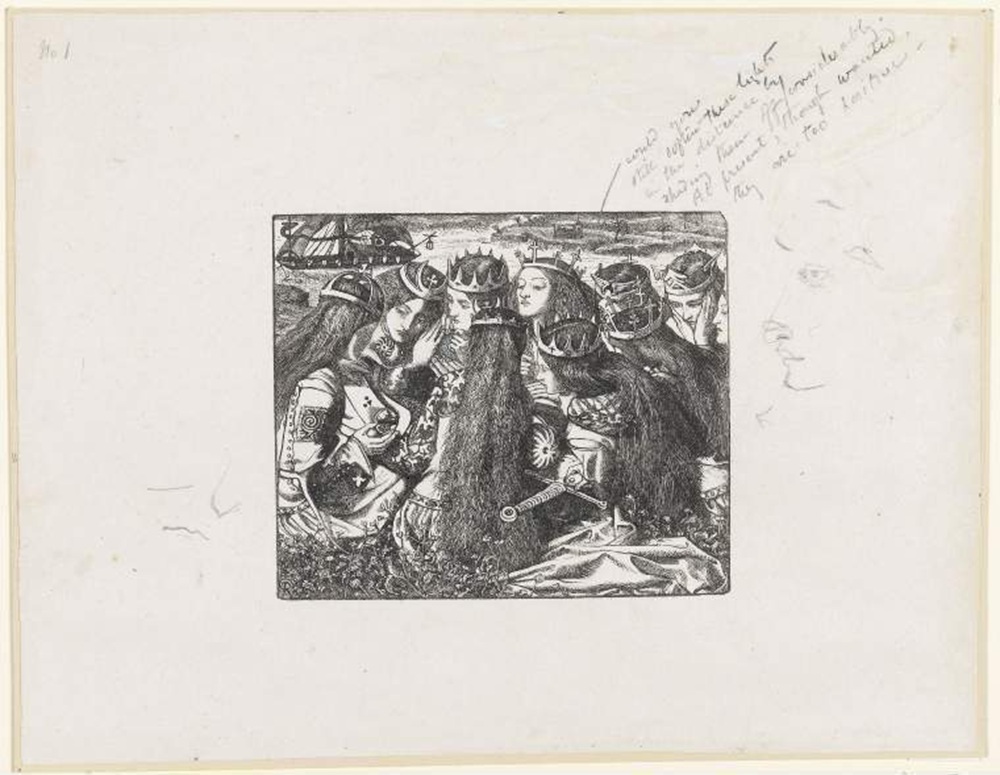

This is the first proof of King Arthur in the Vale of Avalon, the second illustration for Tennyson’s ‘The Palace of Art’.

Head no. 1 Cut away a black within the brow here

Head no. 2 This still wants more delicacy. Cut from above the upper lip with more curve as marked. Make the eyebrow more delicate, Cut outside the nostril, which is still wide & cut across the black at further end of mouth, Also cut still within the check and chin as marked, and lighten the shadow under the chin.

Head no. 3 Cut away a jot [?] within the chin were felt [?] in both places to lengthen it.

Head no 4 Cut quite away the little line below th eye as marked with white.

Cut away still within the [?] of the nose as marked.

Profile head Cut quite away the shadow between the eye and nose as marked.

K. Arthur Cut the upper edge of the beard a little more fringery [like a fringe?]

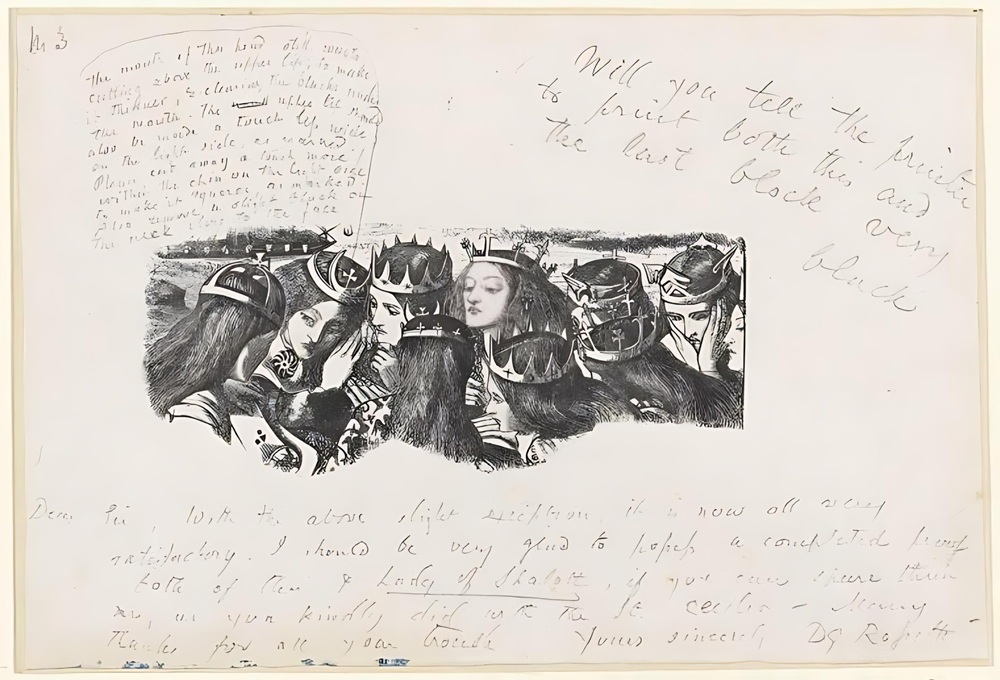

Proof 2

This is the second proof of King Arthur in the Vale of Avalon.

Will you tell the printer to print both this and the last block very black

[bottom of page]

Dear Sir, with the above slight exception, it is now all very satisfactory. I shall be very glad to see [?] a completed proof both of them & Lady of Shalott, if you can spare them me, as you kindly did with the St Cecilia – many thanks for all your trouble. Yours sincerely D. G. Rossetti

No 3

Second figure from left

The mouth of this head still wants cutting above the upper lip; to make it thinner, & clearing the blacks under the mouth. The upper lip should also be made a touch less wide on the light side, as marked. Pleas cut away a touch more within the chin on the light side to make it squarer, as marked. Also remove a slight black on the next close to the face.

Proof 3

The third and final proof King Arthur in the Vale of Avalon, which has been assembled to create the completed image.

Would you still soften these lights in the distance by shading them of considerably. At present though marked, they are too positive

Rossetti’s Priorities

Rossetti’s annotations reveal his concern with modelling, perspective, and the relationship between the fore and background. In his instructions for St Cecilia he focuses on improving the definition of the main figures – the saint, the angel and the soldier – while also enhancing the details of their faces and heads. Writing of Cecilia, he directs the engravers to thin the lines surrounding the saint’s ‘bosom’ while lightening the forehead and cutting away ‘inside the point of her chin, to make it sharper.’ The angel’s hair might also be refined, as might the soldier’s expression, which needs to have more expression in his eyes and clearer definition of ‘the mouth and fingers.’ Rossetti also provides detailed revisions of the heads of the grieving queens in King Arthur. These are subject to intricate alterations in pursuit of ‘delicacy’ and expression in which he draws attention to a number of minute cuts to narrow a mouth or make a chin ‘squarer,’ redefine a lip or ‘lighten the shadow’ under a chin.

At the same time, he insists on an improved use of light as a means of differentiating between the fore and background. In St Cecilia, he comments on the need to ‘Broaden the light on the apple’ and ‘whiten the rose’ while making sure that the ‘figures are … made rather lighter & the distance rather darker.’ He makes the same request of the completed proof for King Arthur (proof 3), noting how the ‘lights in the distance’ are ‘too positive’ and need to be shaded out ‘considerably.’

Some Inconsistencies

These corrections are generally very specific and, as noted earlier, reflect the artist’s need to produce the best possible result and one which emulates the effects of painting. Nevertheless, some of his comments could be subject to misinterpretation. Always seeming very exact, remarks such as ‘cut quite away’ and ‘a touch or two’ are in reality quite vague, and it is not surprising to hear that the Dalziels were sometimes as frustrated with Rossetti as he was with them – despite the polite tone of his direct address and ‘Many thanks for so much care’(proof 1).

In the end, inevitably, it was a matter of compromise, with the artist achieving as near to his desired effect as possible, given the constraints of the engravers’ skill and the characteristics of the medium. As noted earlier, Rossetti misunderstood the linear nature of wood cutting and makes demands, mainly to do with the abstract effects of light, that are near-impossible to achieve in a form that is not painting. Telling the engraver to make the soldier’s eyes in St Cecilia ‘indistinct’ is a prime example of this sort of incomprehension, but it is remarkable to see how close to the original design the engraved print turns out to be.

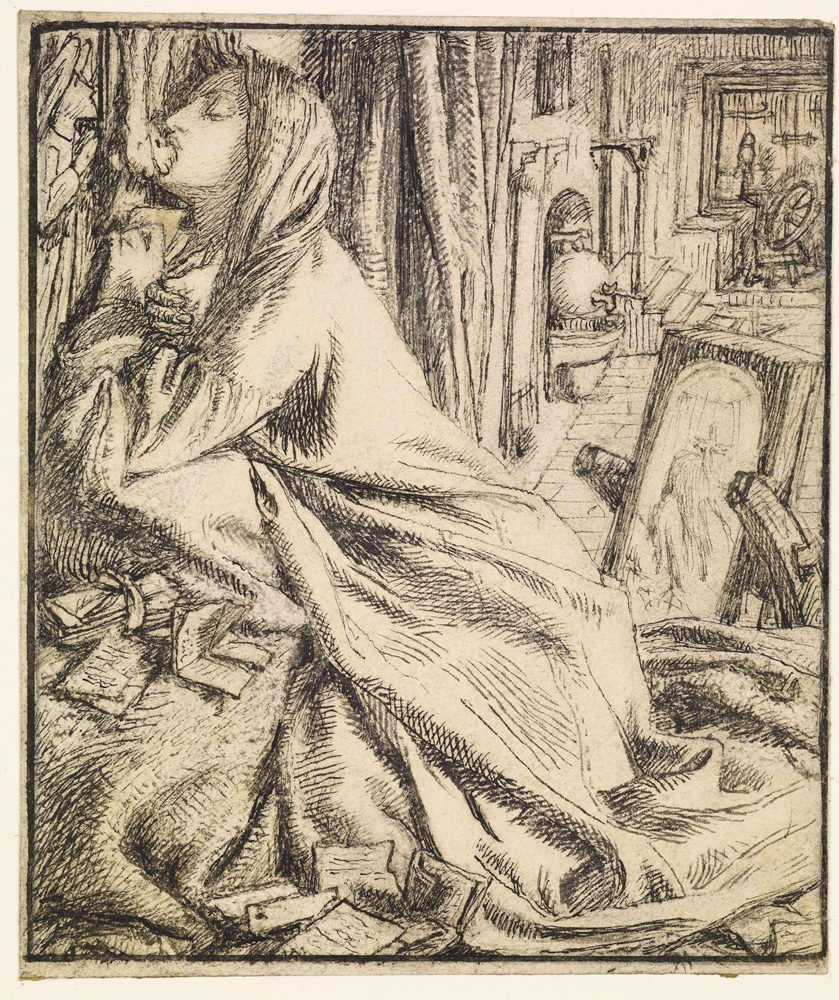

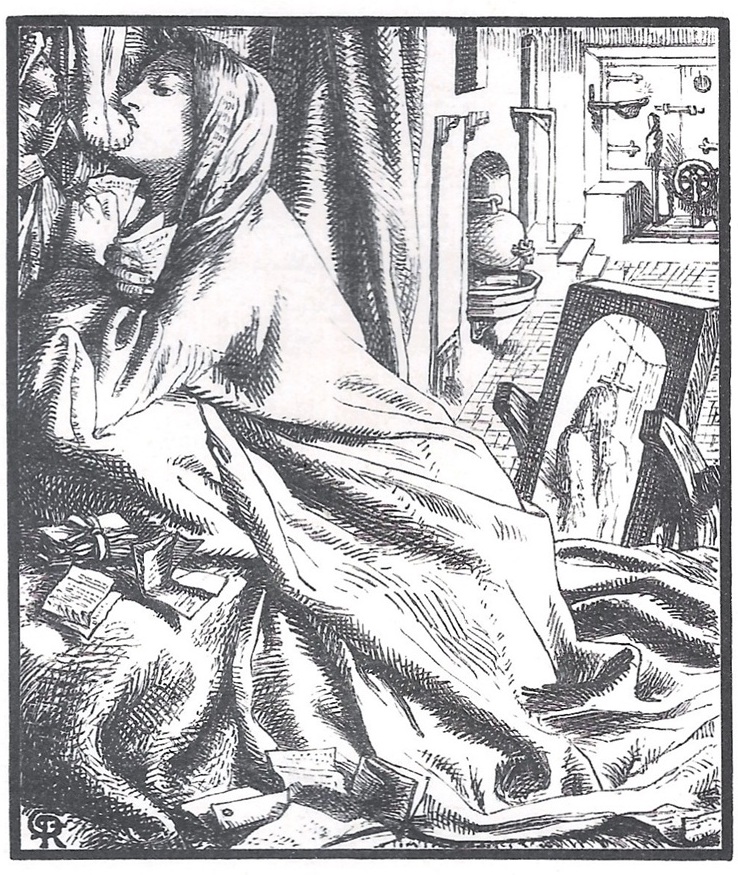

Yet there is one glaring, and puzzling difference between the original drawing and the finished print. In the primary work the angel looks at the Saint, but in the engraving he kisses her forehead. Rossetti makes no comment on this, an extraordinary omission given his nit-picking comments on the smallest of details.

Left: The original drawing for St Cecilia; and right: the Dalziels’ engraved version.

But whatever the difficulties, Rossetti’s engravings were generally in line with his drawings. Despite Rossetti’s complaint that the Dalziels had ‘hewn’ his work into an incoherent mess (Hill 191), the reality is that their work is remarkably faithful to the artist’s poetic prototypes. A comparison between the original design for King Arthur and the published cut shows how accurate the process of translation could be, even bearing in mind some slippages and minor differences in the detail; and the same is true of the relationship between the drawing and engraving of Mariana in the South, which was cut by William Linton rather than the Dalziels. Rossetti’s work is exquisite, and to the objective eye the final prints are just about as beautiful a version as they could be, retaining the poetic ambience of the artist’s vision in an intricate skein of minute and painstaking lines. The product of craft, the cuts are works of art in their own right.

Left: The original drawing for King Arthur in the Vale of Avalon; and Right: the Dalziels’ engraved version.

Left: The original drawing for Mariana in the South; and Right: the Dalziels’ interpretation of Rossetti’s original.

Bibliography

The Brothers Dalziel, A Record of Work, 1840-1890. 1901; reprinted London: Batsford, 1978.

Hill, George Birbeck. Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Letters to William Allingham, 1854–1870. London: Fisher Unwin, 1897.

Tennyson, Alfred. Poems. London: Moxon, 1857.

Created 10 August 2025