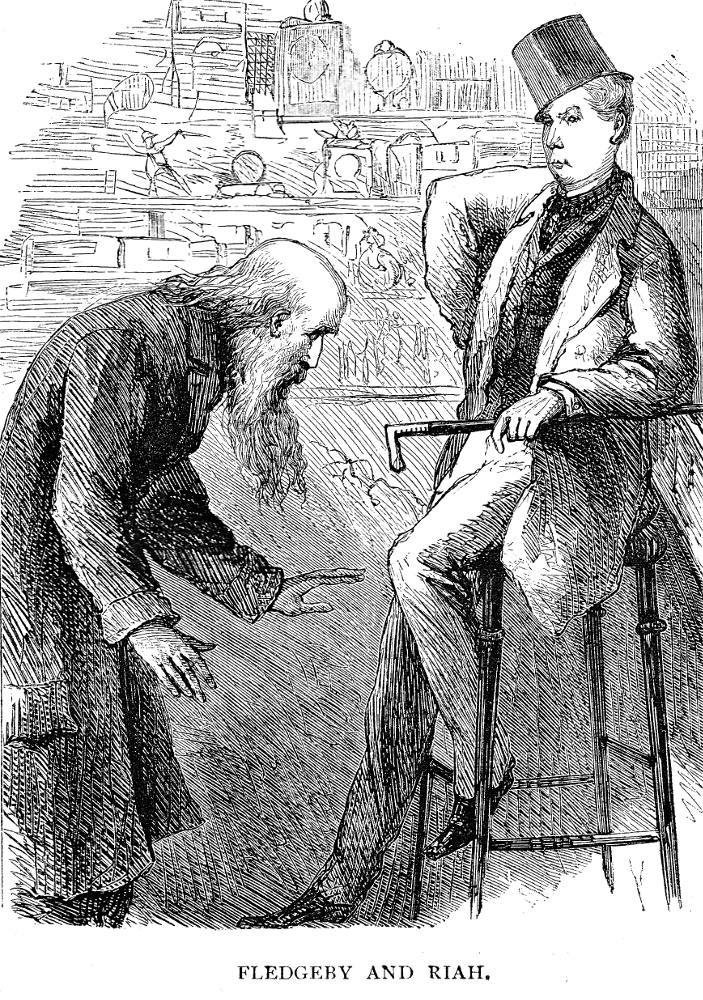

Fledgeby and Riah

Sol Eytinge

Composite woodblock engraving

1867

9.9 cm high by 7.4 cm wide (3 ⅞ by 2 ⅞ inches), frontispiece for Dickens's Our Mutual Friend in the Diamond Edition (Boston: Ticknor & Fields), facing page 163.

[Click on image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.