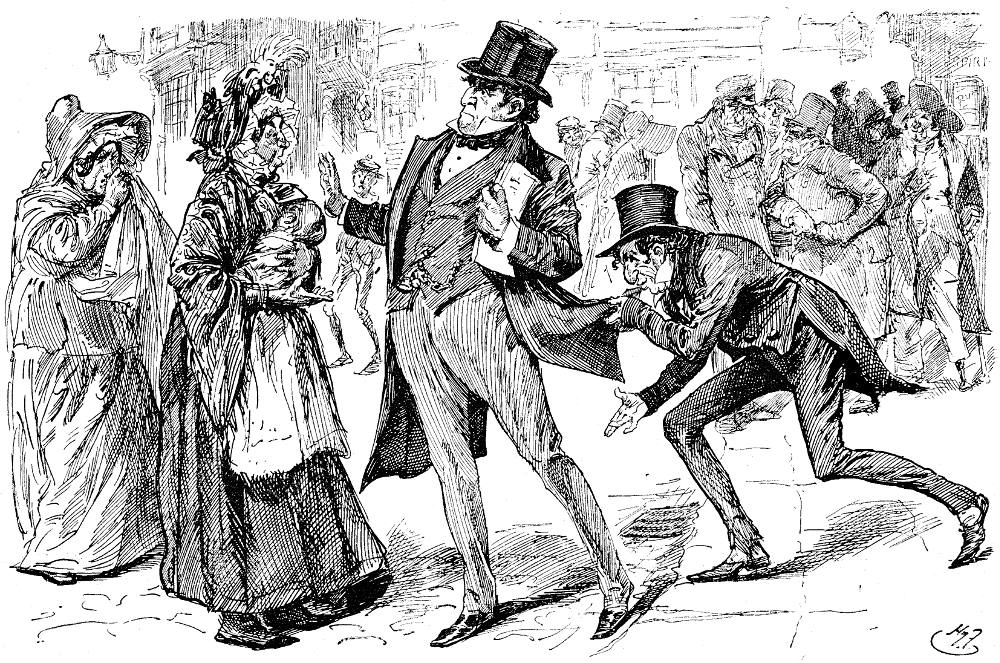

"Say another word — one single word — and Wemmick shall give you your money back" by F. A. Fraser (1844-1896). 10.7 cm high by 13.8 cm wide (4 ⅛ by 5 ⅜ inches), framed (half-page, horizontally mounted), p. 77, Chapter Twenty, in Charles Dickens's Great Expectations, which appeared as Volume 11 in the British Household Edition (1876). Running head: "Mr. Jaggers's Clients" (77). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Passage Illustrated: Jaggers meets some disreputable clients in the streets near his office

At length, as I was looking out at the iron gate of Bartholomew Close into Little Britain, I saw Mr. Jaggers coming across the road towards me. All the others who were waiting saw him at the same time, and there was quite a rush at him. Mr. Jaggers, putting a hand on my shoulder and walking me on at his side without saying anything to me, addressed himself to his followers.

First, he took the two secret men.

“Now, I have nothing to say to you,” said Mr. Jaggers, throwing his finger at them. “I want to know no more than I know. As to the result, it’s a toss-up. I told you from the first it was a toss-up. Have you paid Wemmick?”

“We made the money up this morning, sir,” said one of the men, submissively, while the other perused Mr. Jaggers’s face.

“I don’t ask you when you made it up, or where, or whether you made it up at all. Has Wemmick got it?”

“Yes, sir,” said both the men together.

“Very well; then you may go. Now, I won’t have it!” said Mr. Jaggers, waving his hand at them to put them behind him. “If you say a word to me, I’ll throw up the case.”

“We thought, Mr. Jaggers —” one of the men began, pulling off his hat.

“That’s what I told you not to do,” said Mr. Jaggers. “You thought! I think for you; that’s enough for you. If I want you, I know where to find you; I don’t want you to find me. Now I won’t have it. I won’t hear a word.”

The two men looked at one another as Mr. Jaggers waved them behind again, and humbly fell back and were heard no more.

“And now you!” said Mr. Jaggers, suddenly stopping, and turning on the two women with the shawls, from whom the three men had meekly separated, —“Oh! Amelia, is it?”

“Yes, Mr. Jaggers.”

“And do you remember,” retorted Mr. Jaggers, “that but for me you wouldn’t be here and couldn’t be here?”

“O yes, sir!” exclaimed both women together. “Lord bless you, sir, well we knows that!”

“Then why,” said Mr. Jaggers, “do you come here?”

“My Bill, sir!” the crying woman pleaded.

“Now, I tell you what!” said Mr. Jaggers. “Once for all. If you don’t know that your Bill’s in good hands, I know it. And if you come here bothering about your Bill, I’ll make an example of both your Bill and you, and let him slip through my fingers. Have you paid Wemmick?”

“O yes, sir! Every farden.”

“Very well. Then you have done all you have got to do. Say another word — one single word — and Wemmick shall give you your money back.”

This terrible threat caused the two women to fall off immediately. No one remained now but the excitable Jew, who had already raised the skirts of Mr. Jaggers’s coat to his lips several times. [Chapter XX, 77-78]

Commentar: Criminal Attorney Jaggers puts his clients in their place

Sol Eytinge, Junior's 1867 portrait of the stern criminal attorney: Jaggers, in the Diamond Edition.

Once Jaggers has announced that Pip has come into "Great Expectations," and Pip has prepared for his coach ride to London by purchasing a made-to-measure suit at Trabbs' shop in the village, he bids farewell to Joe and Biddy at the forge. His introduction to the metropolis through the characters of Jaggers, his clerk, Wemmick, and several suspicious-looking street people who are clients initiates Pip and the reader into the second phase of the novel.

Although Dickens has narrated the scene from the perspective of the protagonist in the first-person, Fraser again has organized it with an embedded viewer: in this instance, Pip himself. We can be forgiven for not instantly recognizing the smartly dressed young Londoner at Jaggers' side as the former blacksmith's apprentice from the Marshes. This slight, smooth-faced young Regency buck in fashionable, light-coloured stirrup pants (all the fashion in Dickens's youth) and cutaway morning coat looks away, as if distracted by the sights, sounds, and perhaps even the smells of the working-class borough known as Little Britain. Whereas a respectable porter walks out of frame to the left, to the right Fraser has placed two women in shawls, and a single scruffy street character, his hands open in appeal. What connects this image of Pip with the one in the previous illustration, set in Trabb's shop, is the cane, which now resembles a riding-crop. As in the text, perhaps as a gesture of protection and reassurance, Jaggers places one hand upon Pip's shoulder as he uses his left hand to point sharply at the women speaking to him. Evidently the precise moment realised is when Jaggers turns on the two women in shawls, and addresses Amelia. She is crying about her husband, Bill, whose case Jaggers has already accepted.

Fraser indicates little about the scene's physical setting, St. Bartholomew's Close in the formerly fashionable Little Britain. The narrow streets and dilapidated houses had by Dickens's time become synonymous with the more disreputable parts of the metropolis, characterized by Smithfield Lane and Bull-in-Mouth street, not far from Butcher Lane and Newgate Prison. Harry Furniss in the Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910) appears to have based a parallel lithograph of Pip and Jaggers in the street directly on this Fraser wood-engraving.

Images of the Formidable Jaggers from Other Editions

Left: A Rubber at Miss Havisham's (1862), from theIllustrated Library Edition by Marcus Stone. Centre: In the first American serialisation, periodical illustrator John McLenan realizes Jaggers's candour with his criminal clients: "You infernal scoundrel, how dare you tell me that?" (23 February 1861). Right: Harry Furniss's realisation of the same scene: Mr Jaggers and His Clients (1910).

Related Material

- Criminally Self-Conscious: Pip's "Great Expectations"

- Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations

- Bibliography of works relevant to illustrations of Great Expectations

- Francis A. Fraser’s Illustrations of "The Seven Poor Travellers" by Charles Dickens (1911)

- Francis A. Fraser’s Illustrations of "The Perils of Certain English Prisoners" by Charles Dickens (1911)

Other Artists’ Illustrations for Dickens's Great Expectations

- Edward Ardizzone (2 plates selected)

- H. M. Brock (8 lithographs)

- J. Clayton Clarke ("Kyd") (2 lithographs from watercolours)

- Felix O. C. Darley (2 plates)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr. (8 wood engravings)

- Marcus Stone (8 wood engravings)

- John McLenan (40 wood engravings)

- Harry Furniss (28 plates)

- Charles Green (10 lithographs)

- Frederic W. Pailthorpe (21 lithographs)

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Allingham, Philip V. "The Illustrations for Great Expectations in Harper's Weekly (1860-61) and in the Illustrated Library Edition (1862) — 'Reading by the Light of Illustration'." Dickens Studies Annual, Vol. 40 (2009): 113-169.

Dickens, Charles. Great Expectations. Illustrated by John McLenan. [The First American Edition]. Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization, Vols. IV: 740 through V: 495 (24 November 1860-3 August 1861).

______. ("Boz."). Great Expectations. With thirty-four illustrations from original designs by John McLenan. Philadelphia: T. B. Peterson (by agreement with Harper & Bros., New York), 1861.

______. Great Expectations. Illustrated by Marcus Stone. The Illustrated Library Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1862. Rpt. in The Nonesuch Dickens, Great Expectations and Hard Times. London: Nonesuch, 1937; Overlook and Worth Presses, 2005.

______. A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. 16 vols. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

______. Great Expectations. Volume 6 of the Household Edition. Illustrated by F. A. Fraser. London: Chapman and Hall, 1876.

______. Great Expectations. The Gadshill Edition. Illustrated by Charles Green. London: Chapman and Hall, 1898.

______. Great Expectations. The Grande Luxe Edition, ed. Richard Garnett. Illustrated by Clayton J. Clarke ('Kyd'). London: Merrill and Baker, 1900.

______. Great Expectations. "With 28 Original Plates by Harry Furniss." Volume 14 of the Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book Co., 1910.

Created 14 February 2004 Last modified 27 August 2021