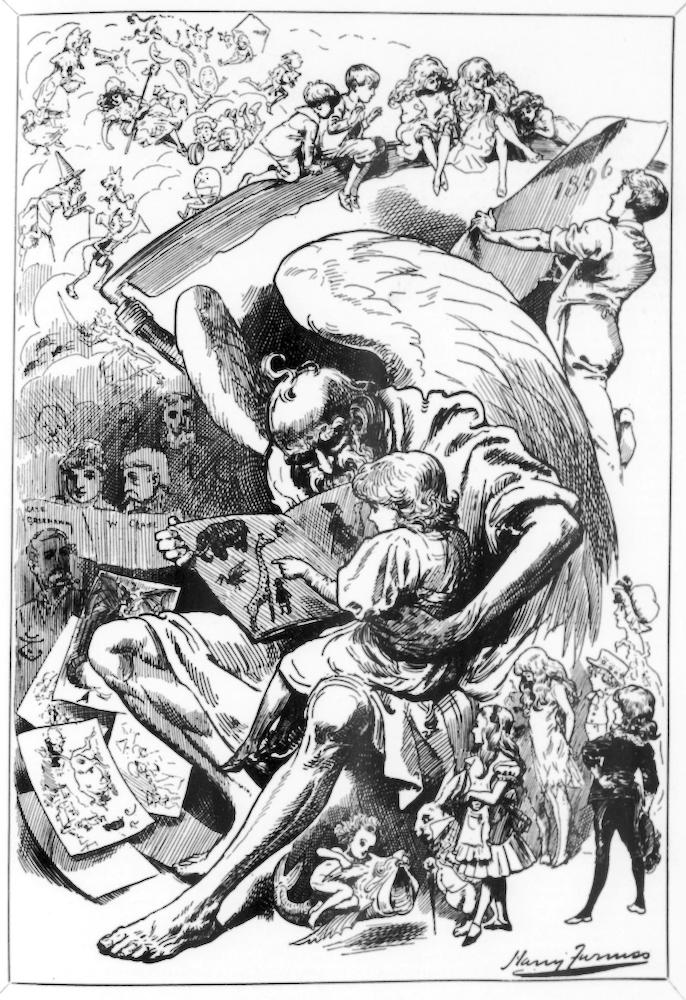

Illustrations and Illustrators by Harry Furniss (1854-1925). Left: The whole cartoon. Right: Illustrations of some well-known characters on the right. Art Journal (May 1896), p. 159. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

At the centre of this tribute to, and comment on, this contemporary art form and some of his famous fellow-practitioners in the field, Furniss depicts not an ogre, as might first be assumed, but a winged and top-knotted Father Time. Having set aside his scythe, which rests harmlessly on his shoulder, Father Time is showing a picture book to a little girl who sits comfortably on his knee. She is pointing at the likeness of a giraffe, one of the curiosities to which the British had only been introduced earlier in that century (1836, when one arrived at London Zoo). More children perch happily on the edge of Father Time's scythe, looking with evident interest at another book held open for them by a young lad wearing a workman's (perhaps a printer's or etcher's) apron: this one has "1896" on its cover. In the lower right foreground can be seen some characters from children's literature: from left to right, Charles Kingsley's water baby Tom, sitting on a fish; the white rabbit with Alice from Alice in Wonderland, and another of Lewis Carroll's characters, Sylvie from Sylvie and Bruno of 1889; a girl and boy in costumes like those created by Kate Greenaway; and on the far right Little Lord Fauntleroy, from Frances Burnett's novel of 1886.

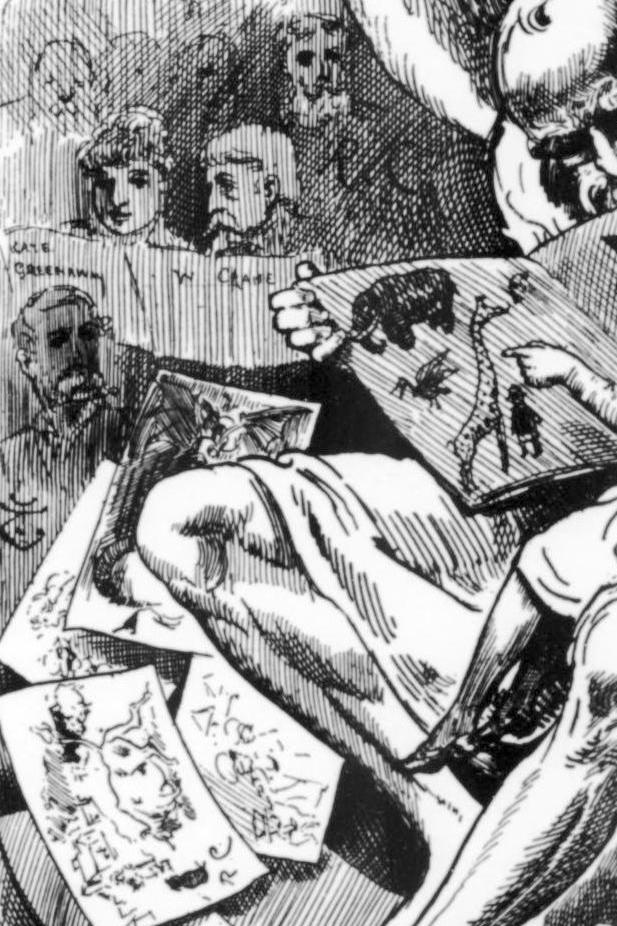

Four famous illustrators commemorated by Furniss, whose signatures can be identified: Kate Greenaway and Walter Crane; John Tenniel; and Randolph Caldecott.

As the illustrator of Sylvie and Bruno and its sequel, it was natural that Furniss should include one of the characters he himself had depicted, although this one lacks the iconic status which the others have achieved. But the illustrators he actually shows and names are Kate Greenaway herself, and Walter Crane, sitting together on the left, their signatures identifying them, John Tenniel just below them, with his well-known monogram at the side of his jacket, and above them Randolph Caldecott, with an indistinct "RC" on a darker jacket. There are also some more tiny characters from illustrated books in the top left, including Caldecoott's cow jumping over the moon at the very top; and sitting dangerously on the edge of the scythe is Humpty Dumpty. He seems to be sliding down it.... It is such a rich medley of artists and their most memorable creations.

Noting the deeper implications here, Julia Thomas sees the cartoon not only as a "crowded homage to the great names in children's illustrated literature" but as as "a grouping that both invites and replicates the networked process by which the illustrated texts were read and consumed" — yielding a body of work that had, indeed, "become an integral part of Victorian culture" (132).

Furniss's tribute to this galaxy of "illustrations and illustrators" certainly indicates their importance in presenting and preserving, in their unique ways, some of the best-loved characters of Victorian books and periodicals. Images stamped so indelibly on the mind for decades and even centuries, do show that even Father Time can be stilled by the power of the creative imagination.

Scanned images and text by Jacqueline Banerjee. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned them and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

The Art Journal, New series (May 1896). Internet Archive, from a copy in California State Library. Web. 15 April 2025.

Thomas, Julia. The Victorian Mind’s Eye: Reading Literature in an Age of Illustration. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2025. [Review by Simon Cooke.]

Created 15 April 2025