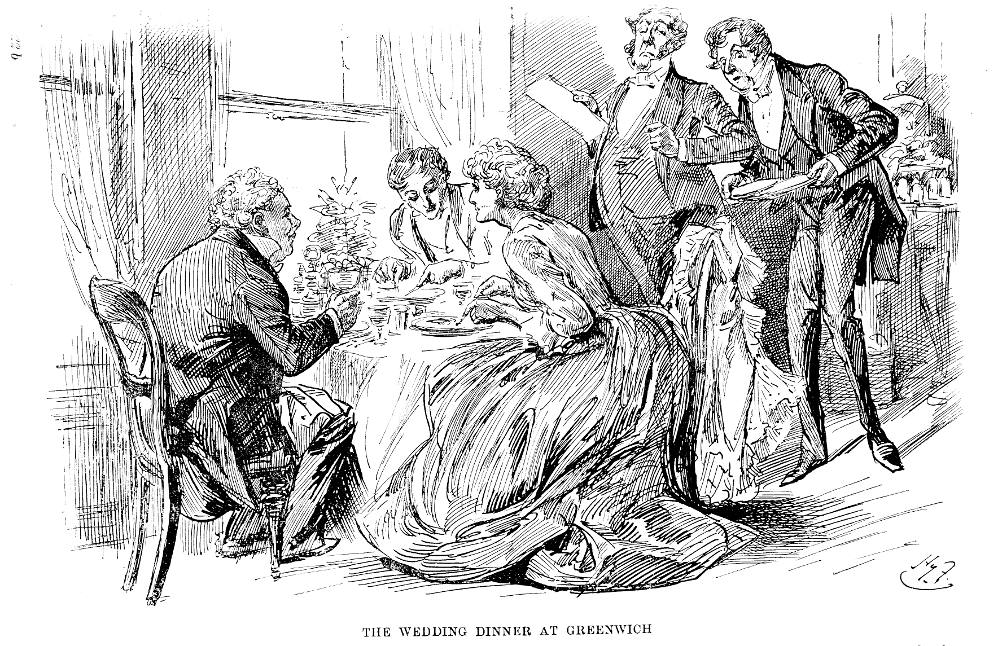

The Wedding Dinner at Greenwich by Harry Furniss. 9 cm by 13.7 cm, or 3 ½ by 5 ½ inches, vignetted. Dickens's Our Mutual Friend, facing XV, 704, in Book IV, “A Turning,” Chapter IV, “A Runaway Match,” in The Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Bella sat between Pa and John, and divided her attentions pretty equally. There was an innocent young waiter of a slender form and with weakish legs, as yet unversed in the wiles of waiterhood; him the dignified head waiter perpetually obstructed, cutting him out with his elbow in the moment of success. — Our Mutual, p. 696.

Passage Illustrated: Furniss's Take on a Staple of this Romance

What a dinner! Specimens of all the fishes that swim in the sea, surely had swum their way to it, and if samples of the fishes of divers colours that made a speech in the Arabian Nights (quite a ministerial explanation in respect of cloudiness), and then jumped out of the frying-pan, were not to be recognized, it was only because they had all become of one hue by being cooked in batter among the whitebait. And the dishes being seasoned with Bliss — an article which they are sometimes out of, at Greenwich — were of perfect flavour, and the golden drinks had been bottled in the golden age and hoarding up their sparkles ever since.

The best of it was, that Bella and John and the cherub had made a covenant that they would not reveal to mortal eyes any appearance whatever of being a wedding party. Now, the supervising dignitary, the Archbishop of Greenwich, knew this as well as if he had performed the nuptial ceremony. And the loftiness with which his Grace entered into their confidence without being invited, and insisted on a show of keeping the waiters out of it, was the crowning glory of the entertainment.

There was an innocent young waiter of a slender form and with weakish legs, as yet unversed in the wiles of waiterhood, and but too evidently of a romantic temperament, and deeply (it were not too much to add hopelessly) in love with some young female not aware of his merit. This guileless youth, descrying the position of affairs, which even his innocence could not mistake, limited his waiting to languishing admiringly against the sideboard when Bella didn’t want anything, and swooping at her when she did. Him, his Grace the Archbishop perpetually obstructed, cutting him out with his elbow in the moment of success, despatching him in degrading quest of melted butter, and, when by any chance he got hold of any dish worth having, bereaving him of it, and ordering him to stand back.

‘Pray excuse him, madam,’ said the Archbishop in a low stately voice; ‘he is a very young man on liking, and we don’t like him.’

This induced John Rokesmith to observe — by way of making the thing more natural — ‘Bella, my love, this is so much more successful than any of our past anniversaries, that I think we must keep our future anniversaries here.’ [Book Four, Chapter IV, “A Runaway Match,” 696]

Commentary: Romance after Gloom, Marriage after Contemplated Murder

“The Wedding Dinner at Greenwich” succeeds the “runaway match” to which Dickens alludes in the chapter title. The ritualistic repast presided over by an officious Archbishop of a head-waiter celebrates the wedding of Bella Wilfer and John Rokesmith, who have just clandestinely met and married in the church at Greenwich, with Bella's father, R. W., and a pensioner of the Greenwich Naval Hospital ("Gruff and Glum," as they mentally nickname him) as witnesses.

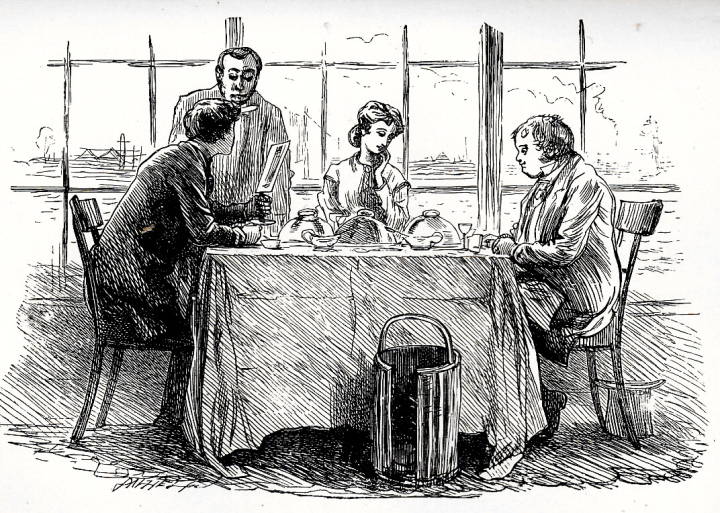

What distinguishes Furniss's revision from the the pallid four-figure Stone original is the sprightliness of the figures and the character comedy of “The Archbishop of Greenwich,” elements entirely lacking in Stone's rather prosaic wood-engraving, despite its detailed treatment of the dining-table. Although Stone provides the necessary realia of the formal diningroom (the epergene, drapes, and sideboard) overlooking the lower reaches of the Thames across from Sir Christopher Wren's magnificent Naval Hospital (barely visible in Stone's original, rear, and not incorporated by Furniss), the composition seems singularly lacking in “inner life.”

Sensibly, Furniss, indeed, has dispensed entirely with the scenery beyond the window in order to focus on the five figures, each individualised not merely by clothing and physiognomy but by gesture and posture: comfortably seated R. W. gestures, John is absorbed in reading the menu, and Bella seems to look past her father to see what lies without — or into her future as a wife. But the piece de résistance is the character comedy of the contrasting older and younger waiters. The Archbishop shuts his eyes in sufferance, completely sure of his command of the menu and the dining circumstances; in contrast, the younger man, a novice uncomfortable in his waiter's uniform, seems so tentative, uncertain, and off-balance, that the viewer becomes apprehensive that he is about to drop those three plates. Thus, Furniss exploits every background detail and every nuance of gesture, pose, and facial expression for comic effect.

Relevant Illustrations in the Serial and Household Editions (1865 and 1875)

Left: Marcus Stone's second serial plate for the August 1865 (sixteenth) number: The Wedding Dinner at Greenwich (Book IV, Chapter 4) suggests that it was the basis for Furniss's illustration. Right: Mahoney's version of the previous dinner scene with the Lammles: The credulous little creature [Georgiana Podsnap] again embraced Mrs. Lammle most affectionately in the fourthbook's secondchapter, "The Golden Dustman Rises a Little." [Click on these images to enlarge them.]

Related Materials

- Illustrations by Marcus Stone (40 plates from the Chapman and Hall edition of May 1864 through November 1865)

- Frontispieces by Octavius Carr Darley (4 photogravures from the Hurd and Houghton Household Edition of 1872)

- Illustrations by Sol Eytinge, Jr. (16 plates from the Ticknor and Fields' Diamond Edition of 1867)

- James Mahoney (58 plates from the Chapman and Hall Household Edition of 1875)

- Harry Furniss (28 lithographs from the Charles Dickens Library Edition, Vol. XV, 1910)

- Clayton J. Clarke (two studies from his designs for the Player's Cigarette Cards, 1910)

Scanned images, captions and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use the images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned them, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1988.

The Characters of Charles Dickens Pourtrayed in a Series of Original Water Colour Sketches by “Kyd.” London, Paris, and New York: Raphael Tuck & Sons, 1898[?].

Cordery, Gareth, and Joseph S. Meisel, eds. The Humours of Parliament: Harry Furniss's View of Late-Victorian Culture. Columbus: The Ohio State University Press, 2014. [Review by Françoise Baillet]

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1999.

Dickens, Charles. Bleak House. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ('Phiz'). London: Bradbury & Evans. Bouverie Street, 1853.

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by Marcus Stone [40 composite wood-block engravings]. The Authentic Edition of the Works of Charles Dickens. 21 vols. London: Chapman and Hall; New York: Charles Scribners' Sons, 1901 [based on the original nineteen-month serial and the two-volume edition of 1865]. Vol. XIV.

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Frontispieces by Felix Octavius Carr Darley and Sir John Gilbert. The Household Edition. 55 vols. New York: Sheldon & Co., 1872. 4 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. 14 vols. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. Vol. VIII.

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by James Mahoney. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1875. Volume IX.

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. XV.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 21: The Other Novels." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. Vol. XVII. Pp. 441-442.

Kitton, Frederic G. Dickens and His Illustrators. London: George Redway, 1899. Rpt. Honolulu: University of Hawaii, 2004.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U.P., 1978. [discussion of dark plate etchings; e-text in Victorian Web.]

Vann, J. Don. "Our Mutual Friend, twenty parts in nineteen monthly instalments, May 1864—November 1865." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985. 74.

Created 13 August 2025