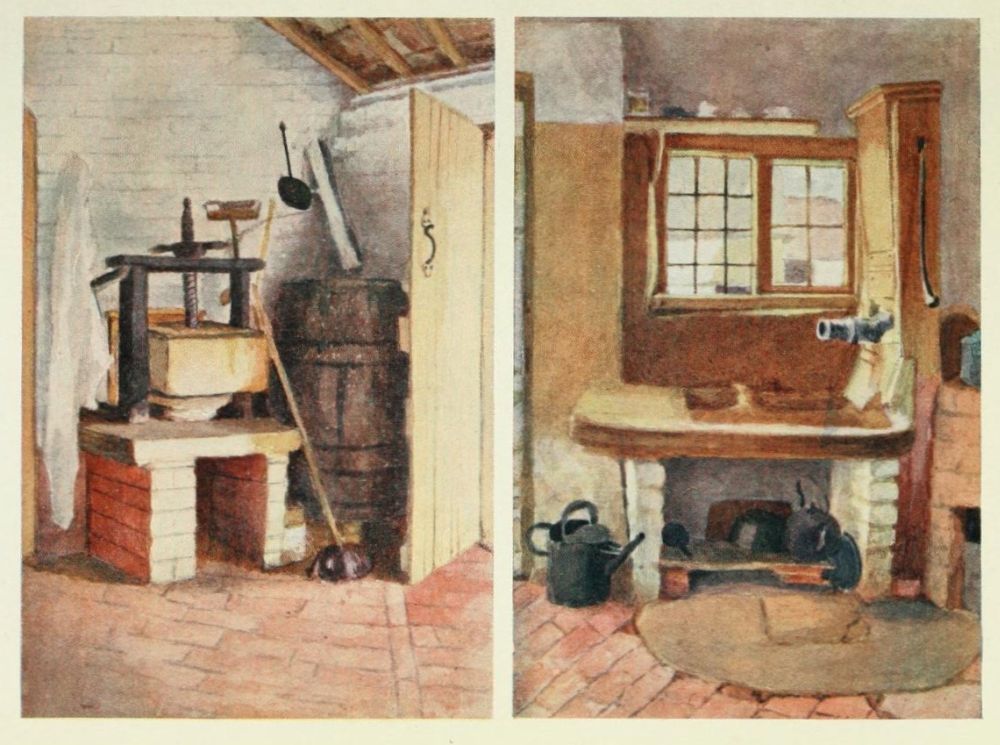

The Kitchen Pump and Old Cheese Press, Rolleston, a coloured drawing by Kate Greenaway (1846-1901), from her childhood visits to her relatives' farm in Rolleston. Source: Spielmann and Layard, facing p.40. Greenaway remembered these early visits with great nostalgia:

She was not a year old when she was taken by her mother to visit her great-aunt, Mrs. Wise, the wife of a farmer at Rolleston, a village some five miles from Newark and fourteen from Nottingham. And Aunt Aldridge, her mother's sister, lived in the neighbourhood, at a lonely farm, weirdly called the "Odd House." At Aunt Wise's house Mrs. Greenaway was taken seriously ill, and it was found necessary to put little Kate out to nurse. Living on a small cottage farm in Rolleston was an old servant of Mrs. Wise's, Mary Barnsdale, at this time married to Thomas Chappell. With the Chappells lived Mary's sister, Ann. It was of this household that Kate became an important member, and forthwith to the child Mary became "Mamam," her husband "Dadad," and her sister Ann "Nanan." This was as soon as she found her tongue. Among her earliest recollections came a hayfield named the "Greet Close," where Ann carried Kate on one arm, and on the other a basket of bread and butter and cups, and, somehow, on a third, a can of steaming tea for the thirsty haymakers — which tells us the season of the year. Kate was sure that she had now arrived at the age of two, and for the rest of her life she vividly remembered the beauty of the afternoon, the look of the sun, the smell of the tea, the perfume of the hay, and the great feeling of Happiness — the joy and the love of it — from her royal perch on Ann's strong arm. ( 10-11)

The passage continues with a description of the little girl collecting pebbles with a friend called Dollie, and the pink cotton frock and white sun-bonnet she wore, before moving on to describe the even greater happiness she derived from flowers, especially wild flowers. It is easy to see how these early experiences inspired her later work, in which she so often depicted children in old-fashioned clothes disporting themselves in rural environments.

But the picture shown here suggests that she had a sharp eye for the realities of her surroundings. Had she been of a different temperament, and had different opportunities presented to her, she might have produced work that her mentor John Ruskin would have valued more. "There is no charm so enduring as that of the real representation of any given scene," he said later, " her present designs are like living flowers flattened to go into an herbarium, and sometimes too pretty to be believed. We must ask her for more descriptive reality, for more convincing simplicity, and we must get her to organize a school of colourists by hand, who can absolutely facsimile her own first drawing" (149). But then perhaps her work would neither have been so immediately recognisable, nor so enduringly popular.

Image download, text and formatting by Jacqueline Banerjee. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit its source and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Engen, Rodney. Kate Greenaway: A Biography. New York: Schocken, 1981.

Ruskin, John. The Art of England: Lectures Given in Oxford. Orpington, Kent: George Allen, 1883. Internet Archive. Web. 10 May 2013.

Spielmann, M. H., and G. S. Layard. Kate Greenaway. London: Adam and Charles Black, 1905. Internet Archive. Web. 10 May 2013.

Last modified 13 May 2013