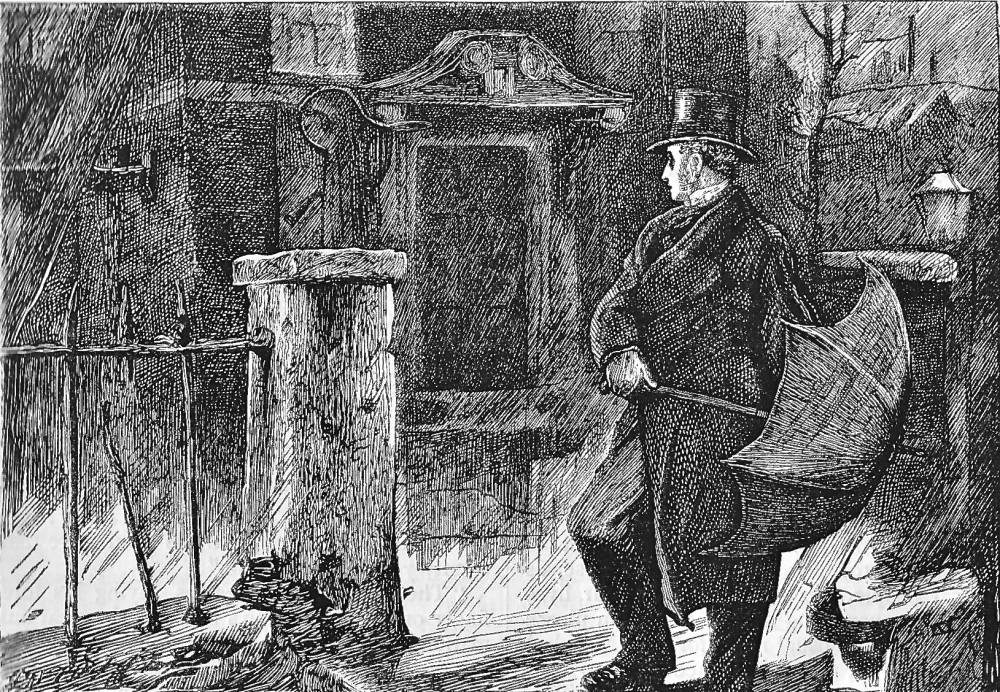

"Nothing changed," said the traveller, stopping to look round. "Dark and miserable as ever." — Book I, chap. 3, Sixties' illustrator James Mahoney's fourth illustration for Charles Dickens's Little Dorrit, Household Edition, 1873. Wood-engraving by the Dalziels, 9.5 cm high x 13.6 cm wide. The Chapman and Hall woodcutand caption are identical to those in the New York (Harper and Brothers) edition. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

Passage Illustrated

Mr. Arthur Clennam took up his hat and buttoned his coat, and walked out. In the country, the rain would have developed a thousand fresh scents, and every drop would have had its bright association with some beautiful form of growth or life. In the city, it developed only foul stale smells, and was a sickly, lukewarm, dirt-stained, wretched addition to the gutters.

He crossed by St. Paul's and went down, at a long angle, almost to the water's edge, through some of the crooked and descending streets which lie (and lay more crookedly and closely then) between the river and Cheapside. Passing, now the mouldy hall of some obsolete Worshipful Company, now the illuminated windows of a Congregationless Church that seemed to be waiting for some adventurous Belzoni to dig it out and discover its history; passing silent warehouses and wharves, and here and there a narrow alley leading to the river, where a wretched little bill, Found Drowned, was weeping on the wet wall; he came at last to the house he sought. An old brick house, so dingy as to be all but black, standing by itself within a gateway. Before it, a square court-yard where a shrub or two and a patch of grass were as rank (which is saying much) as the iron railings enclosing them were rusty; behind it, a jumble of roots. It was a double house, with long, narrow, heavily-framed windows. Many years ago, it had had it in its mind to slide down sideways; it had been propped up, however, and was leaning on some half-dozen gigantic crutches: which gymnasium for the neighbouring cats, weather-stained, smoke-blackened, and overgrown with weeds, appeared in these latter days to be no very sure reliance.

"Nothing changed," said the traveller, stopping to look round. "Dark and miserable as ever. A light in my mother's window, which seems never to have been extinguished since I came home twice a year from school, and dragged my box over this pavement. Well, well, well!"

He went up to the door, which had a projecting canopy in carved work of festooned jack-towels and children's heads with water on the brain, designed after a once-popular monumental pattern, and knocked. A shuffling step was soon heard on the stone floor of the hall, and the door was opened by an old man, bent and dried, but with keen eyes. — Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 3, "Home," p. 16 (originally in the novel's first instalment, December 1855).

Commentary

Arthur Clennam returns to London after an absence of many years in China, where he has been managing the family business. London offers little entertainment, for it is Sunday. Denying himself even the small pleasure of putting up at a coffee house near St. Paul's Cathedral, thirty-something Arthur Clennam feels compelled return to the family mansion, now falling apart, and see his Calvinistic mother, a bitter, wheel-chair-bound invalid.

In the London edition, we encounter the illustration in the midst of the second chapter, "Fellow Travellers," seven pages ahead of the passage realised, so that we anticipate the arrival of the well-dressed young man, umbrella in hand, at the ruined entrance of the dilapidated London mansion, although Mahoney makes it look more like the entrance to a cemetery. The wood-engraving is as dark and melancholy as the opening paragraph of the third chapter, "Home."

At first blush, the gentleman with the large umbrella would seem to be entering a rundown cemetery. Decaying cement and stone, rusting area bars, and what appears to be a large monument (centre) form our impressions of the gloomy, urban scene with multiple chimneys in the background (upper right). Such details accord well with the opening mood of the chapter: "It was a Sunday evening in London, gloomy, close, and stale" (15). Clearly, Arthur Clennam would rather stay at the cheery inn rather than return home through the melancholy, sooty, deserted streets, but he realizes that he has no choice but to revisit the house of his childhood with its redolent associations of oppressive Sundays. Although the house seems unchanged, it is now propped up by enormous timbers, foreshadowing its eventual collapse.

The "traveller" in the act of closing up his umbrella in preparation for entering the dilapidated mansion in a mixed housing and industrial area in London is Arthur Clennam, a thirty-year-old businessman just returned from the family's office in China, presumably Hong Kong. Absent for a decade, the young man in sensible middle-class black has been recalled home after his father's death. But his mother, the stern Calvinist and hard businesswoman, Mrs. Clennam, does not really require his assistance (which she would regard as interference) as she has the services of her confidential clerk, the equally secretive Jeremiah Flintwinch. For Arthur this is a house of secrets, and returning means that he must once again confront them and try to maintain some sort of relationship with his unloving mother, now a bitter invalid, confined to a wheelchair and a second-storey bedroom.

The House and the Clennams from Other Early Editions, 1856-1867

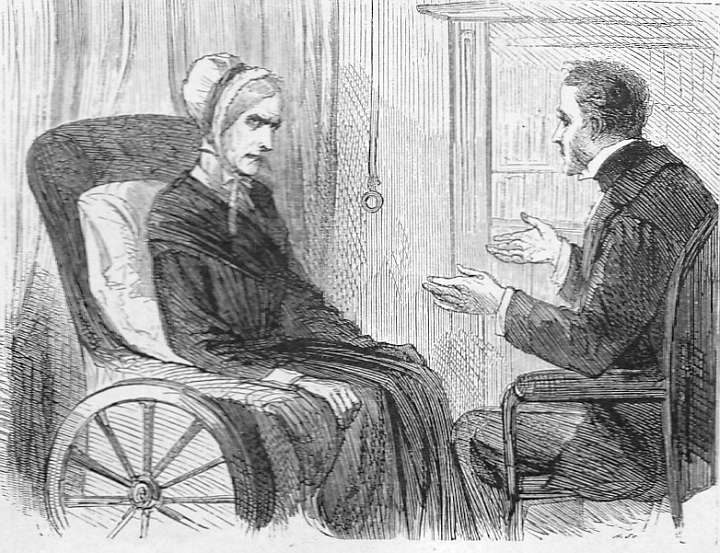

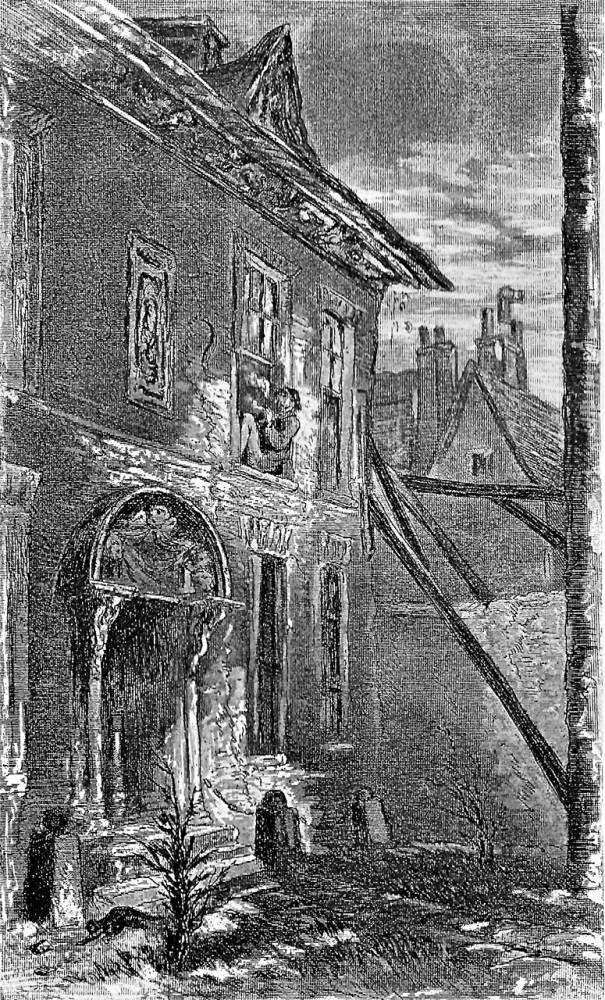

Left: An early American visual interpretation of the dutiful son and the dour mother, Mrs. Clennam and Arthur Clennam. Right: Hablot Knight Browne's interpretation of the ruined Clennam mansion, Damocles from much later in the novel. Parts XIX and XX (Book 2, Chapter 30, "Closing In," and 31, "Closed").(June 1857) [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

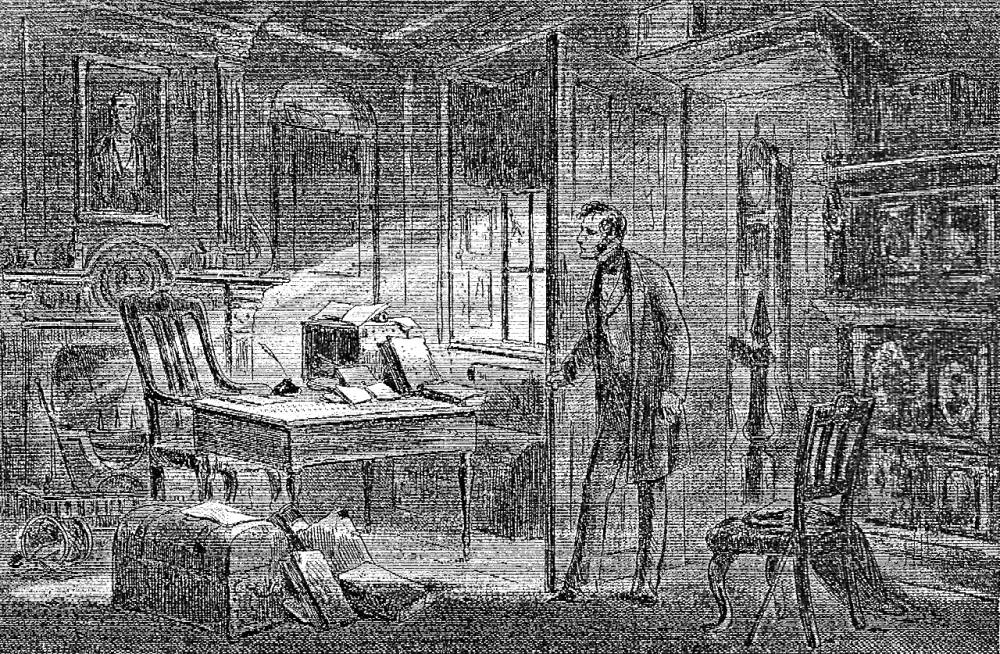

Above: Phiz's original January 1856 engraving of Arthur's entering his father's study in the second serial instalment, The Room with the Portrait. (Part 2: Book One, Chapter 5, "Family Affairs") [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

References

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). The Authentic Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1901 [rpt. of the 1868 volume, based on the 30 May 1857 volume].

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Frontispieces by Felix Octavius Carr Darley and Sir John Gilbert. The Household Edition. 55 vols. New York: Sheldon & Co., 1863. 4 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. 14 vols.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by James Mahoney. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873. Vol. 5.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 12.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 19: Little Dorrit." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Co., 1910. Vol. 17. Pp. 398-427.

Kitton, Frederic George. Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Landseer, Palmer, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. Amsterdam: S. Emmering, 1972. Re-print of the London 1899 edition.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

"Little Dorrit — Fifty-eight Illustrations by James Mahoney." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-six Drawings by Fred Barnard, Gordon Thomson, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), J. McL. Ralston, J. Mahoney, H. French, Charles Green, E. G. Dalziel, A. B. Frost, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1907.

Schlicke, Paul, ed. The Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. P., 1999.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1978.

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985.

Last modified 27 May 2016