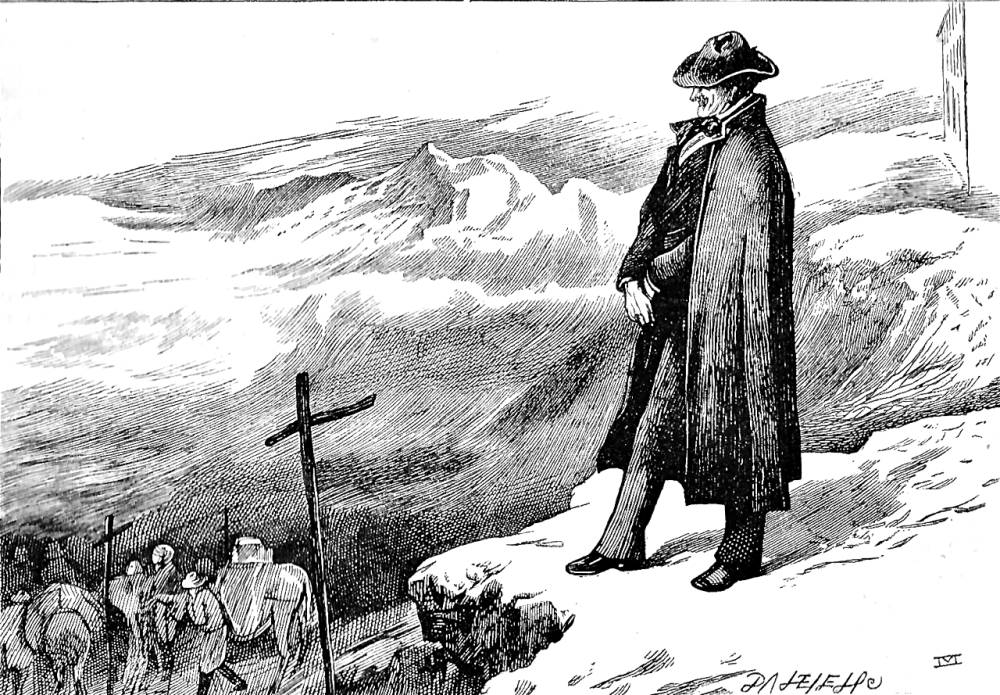

Always standing on one jutting point looking down after them. — Book I, Chapter 3, Sixties' illustrator James Mahoney's thirty-fourth illustration for Charles Dickens's Little Dorrit, Household Edition, 1873. Wood-engraving by the Dalziels, 9.3 cm high x 13.5 cm wide. The Chapman and Hall woodcut is identical to that in the New York (Harper and Brothers) edition, but the American caption is somewhat longer: Nevertheless, as they wound round the rugged way while the convent was yet in sight, she more than once looked round, and descried Mr. Blandois, backed by the convent smoke which rose high from the chimneys in a golden film, always standing on one jutting point looking down after them — Book 2, chap. iii.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

Passage Illustrated

Mr. Gowan stood aloof with his cigar and pencil, but Mr. Blandois was on the spot to pay his respects to the ladies. When he gallantly pulled off his slouched hat to Little Dorrit, she thought he had even a more sinister look, standing swart and cloaked in the snow, than he had in the fire-light over-night. But, as both her father and her sister received his homage with some favour, she refrained from expressing any distrust of him, lest it should prove to be a new blemish derived from her prison birth.

Nevertheless, as they wound down the rugged way while the convent was yet in sight, she more than once looked round, and descried Mr. Blandois, backed by the convent smoke which rose straight and high from the chimneys in a golden film, always standing on one jutting point looking down after them. Long after he was a mere black stick in the snow, she felt as though she could yet see that smile of his, that high nose, and those eyes that were too near it. And even after that, when the convent was gone and some light morning clouds veiled the pass below it, the ghastly skeleton arms by the wayside seemed to be all pointing up at him. — Book the Second, "Riches," Chapter 3, "On the Road," p. 234.

Commentary

Browne's greatest problem was that by now Dickens usurped his very function. The author had always written unusually pictorial prose. In Little Dorrit his writing became so graphically suggestive yet selective that it needed little visual help. [Cohen 114]

Although, as Valerie Browne Lester points out, the illustrations in Little Dorrit are often superfluous because of the descriptive power of the prose, Phiz's realisation of William Dorrit's continuing arrogance and self-importance marks a significant moment in the novel as this is the first illustration in the second book, "Riches." Wealth, as Phiz points out, has done nothing to improve either William or his daughter Fanny; their sudden wealth has merely served to magnify their petulance. Only Amy remains untouched by the unexpected windfall that has enabled the Dorrits to undertake the Grand Tour, complete with couriers and trains of pack-mules. On the other hand, Mahoney's illustration underscoring Blandois' conception of himself as a cunning wolf stalking the English "sheep" he intends to fleece reintroduces the criminal mastermind in the narrative pictorial sequence.

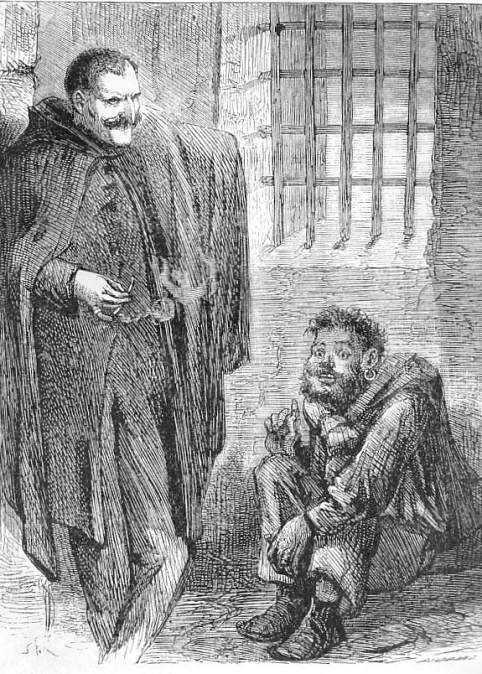

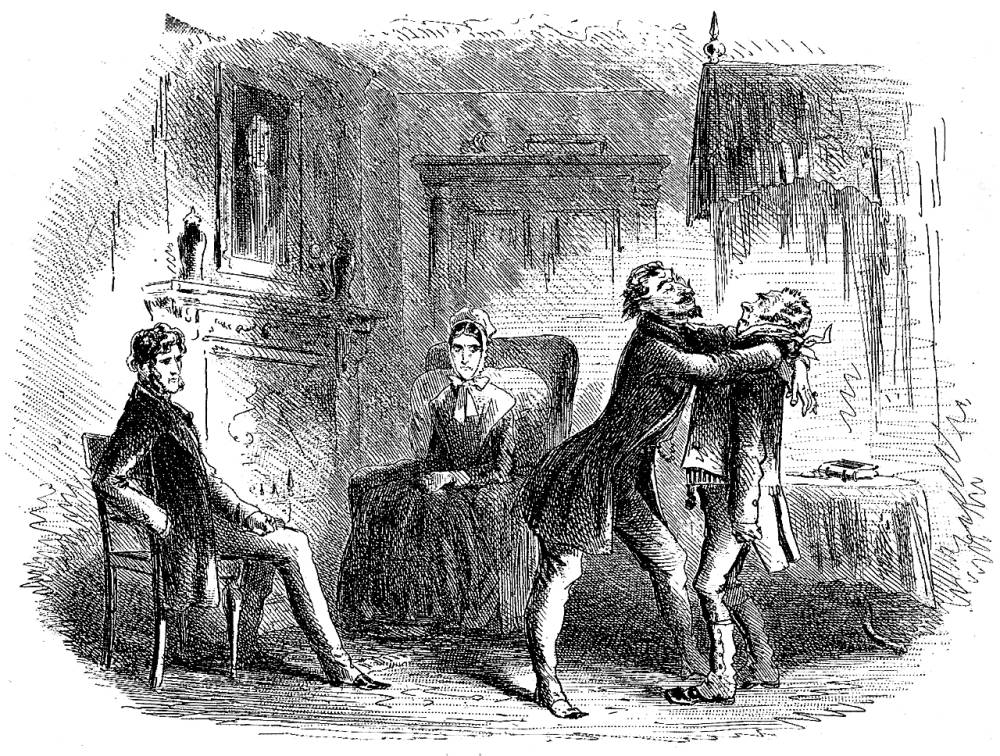

James Mahoney's treatment of the foreign villain in the 1873 Household Edition volume is consistent with Rigaud's malignant appearance in other 19th-century programs of illustration: here we see the same Satanic smirk, the same curling moustache, the same exaggerated nose and Gallic chin (all that are visible of his face in the Mahoney illustration) that one sees in Sol Eytinge, Junior's Rigaud and Cavalletto (1867). The pose of the evil genius watching his prey, however, is rather overstated, and is perhaps even a red herring in terms of the role he will eventually play at Mrs. Clennam's house in London. Mahoney conveys well the majesty of the Alpine backdrop, juxtaposing the dark figure of the sinister observer against the white peaks which the rising sun catches and ruled lines of the valleys still dark after the breakfast scene at the inn. The crosses represent the nearby convent, and a few mules and muleteers imply the presence of a vast train, off left. A relatively minor character in the original serial program who makes just four appearances (discounting his indistinct image in The Birds in the Cage (December 1855) — most significantly in Phiz's Mr. Flintwinch Receives the Embrace of Friendship (Book 2, Chapter 10) — the scoundrel Rigaud is very much a continuing character in Mahoney's program, introduced in the initial illustration in the Marseilles prison. In fact, in the fifty-eight illustrations, Rigaud appears thirteen times, eight of these being in Book the Second. Mahoney may, however, be overstating his importance to the plot, just as Harry Furniss has unreasonably minimized him in the 1910 Charles Dickens Library Edition by showing him just once.

The gentlemanly murderer of his wife, Rigaud (alias Blandois, alias Lagnier) attaches himself to the Gowans when they are honeymooning in Italy, probably with the intention of defrauding them and the other travelling English family, the Dorrits. In England, he allies himseklf with the devious Mrs. Clemman. After he obtains proof that she has suppressed her uncle's will, Rigaud intends to blackmail her, but his plot comes to nought when the Clennam house collapses with him inside it. In his own mind, he is a cosmopolitan lady-killer with exaggerated courtly French manners; Phiz and later illustrators embue him with more than a whiff of Satanic sulfur, emphasized in his smoking cigarettes, and in the Mahoney illustration set in the Alps by his proximity to the smoke from the nearby convent.

Scenes involving Rigaud Blandois in various editions, 1856 to 1910

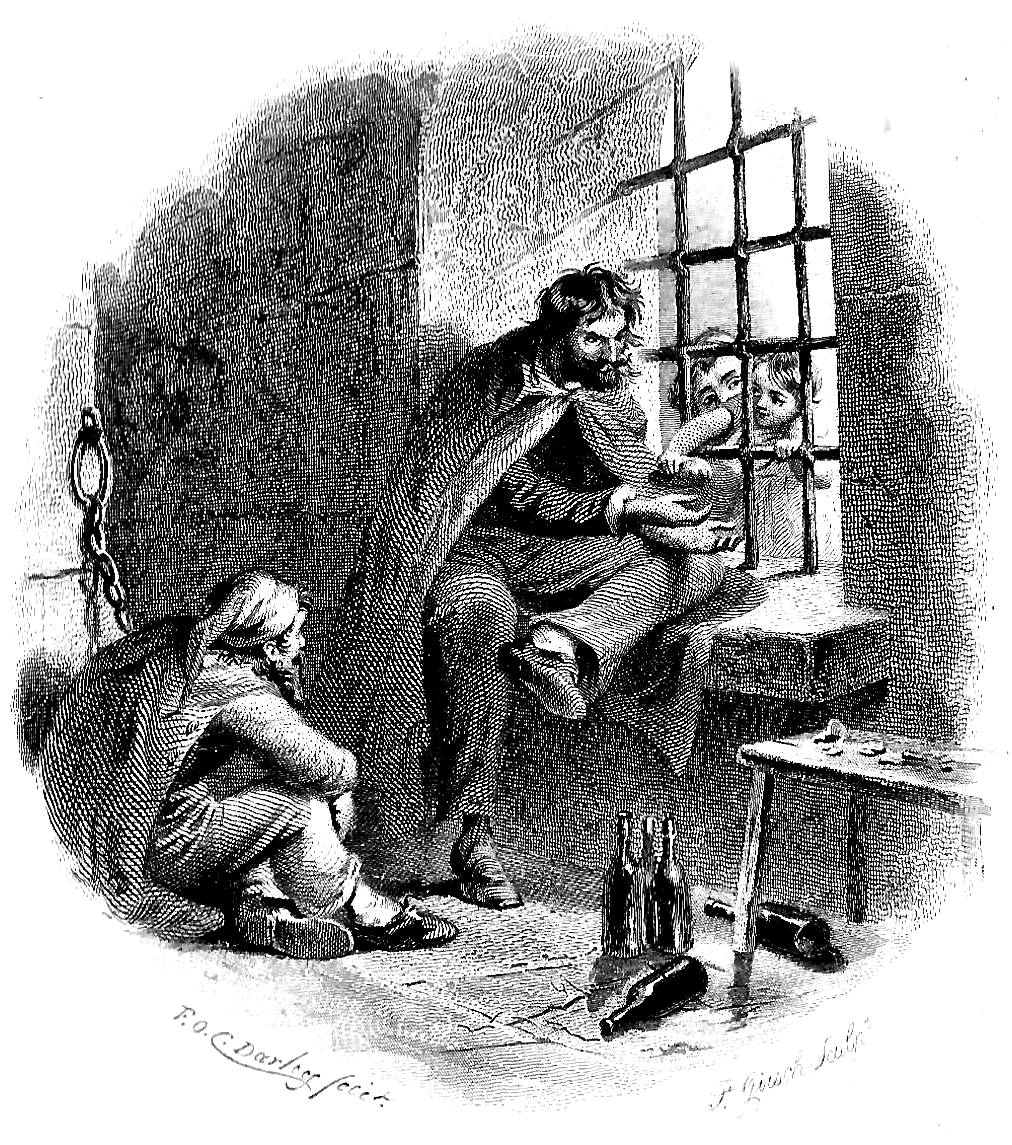

Left: Sol Eytinge, Junior's dual study of the Marseilles prisoners, Rigaud and Cavaletto. Centre: F. O. C. Darley's frontispiece for the first of four 1863 volumes, Feeding the Birds (Household Edition, New York). Right: Harry Furniss's caricature of Rigaud as a comic French housebreaker (Book 1, Chapter 29), in which the Frenchman startles Mistress Affery, Rigaud effects an entrance to Mrs. Clennam's House (1910). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Phiz's December 1856 steel-engraving for monthly part 13, Mr. Flintwinch Receives the Embrace of Friendship (Book 2, ch. 10). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

References

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

The Characters of Charles Dickens pourtrayed in a series of original watercolours by "Kyd." London, Paris, and New York: Raphael Tuck & Sons, n. d.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980.

Darley, Felix Octavius Carr. Character Sketches from Dickens. Philadelphia: Porter and Coates, 1888.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Household Edition. New York: Sheldon and Company, 1863. Vol. 1.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by James Mahoney [58 composite wood-block engravings]. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873.

Dickens, Charles. Little Dorrit. Illustrated by Harry Furniss [29 composite lithographs]. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1919. Vol. 12.

Hammerton, J. A. "Chapter 19: Little Dorrit." The Dickens Picture-Book. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 17. Pp. 398-427.

Kyd [Clayton J. Clarke]. Characters from Dickens. Nottingham: John Player & Sons, 1910.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

"Little Dorrit — Fifty-eight Illustrations by James Mahoney." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-six Drawings by Fred Barnard, Gordon Thomson, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), J. McL. Ralston, J. Mahoney, H. French, Charles Green, E. G. Dalziel, A. B. Frost, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1907.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U.P., 1978.

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: Modern Language Association, 1985.

Last modified 5 April 2016