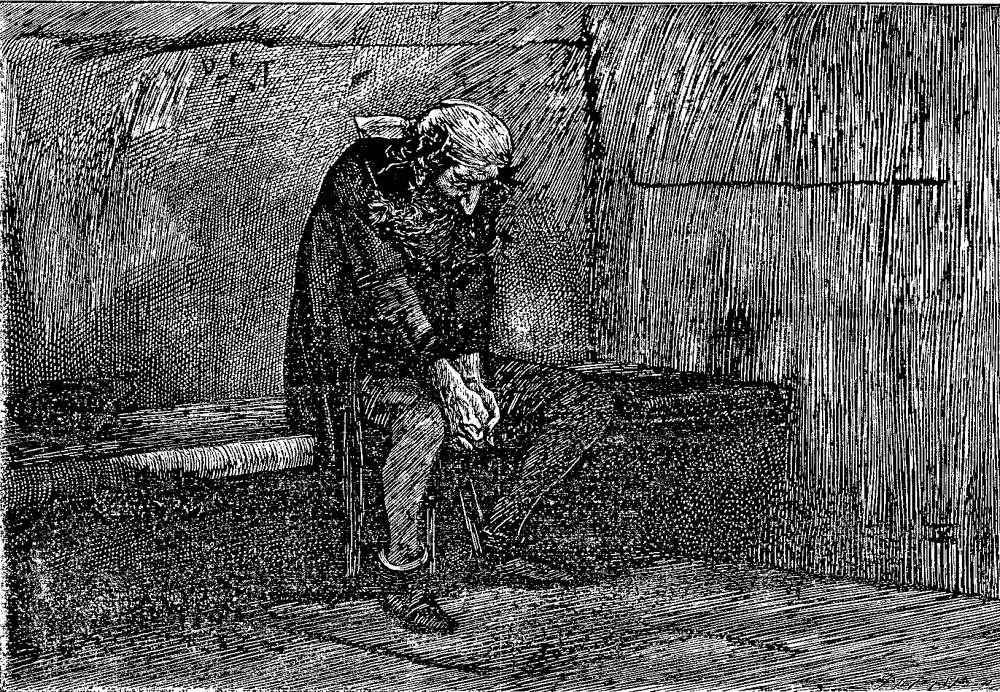

"He sat down on a stone bench opposite the door." — James Mahoney's refashioning of Cruikshank's iconic treatment of the subject, less caricatural but also less dramatic than that probing psychological study in the original serial, November 1838 and 1846 volume editions illustrated by George Cruikshank. As Dickens has already drawn the many strands of the complicated "inheritance" plot together in Chapter 51, for the Household Edition, Mahoney now provides a rendition of the scene in which the condemned prisoner awaits execution at Newgate. In the original narrative-pictorial serial sequence in Bentley's Miscellany for Part 24, April 1839, the periodical reader encountered a neurotic Fagin (in fact, a self-portrait by the illustrator himself) awaiting execution in Fagin in the Condemned Cell in the chapter which was subsequently retitled "Fagin's Last Night Alive," in The Adventures of Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress, the penultimate periodical illustration in Oliver's "Progress." The Mahoney illustration is less melodramatic than Cruikshank's portrait of Fagin (and less psychological) and not sensational in any way, especially in contrast to the previous month's illustration, The Last Chance, in which Sikes makes a desperate attempt to escape apprehension. The common thread here is poetic justice as Sikes dies by his own hand and Fagin, manager and director of a band of criminals and instigatorof Nancy's brutal murder, suffers psychological terror as he awaits his death without the solace of even his mean companions. The passage realised actually occurs on the page opposite, a rarity among the juxtapositions of illustrations and textual passages realised in the Household Edition, so that one may readily integrate a reading of the text on page 200 and an analysis of the illustration on page 201. The illustration is positioned in the middle of Chapter 52. 1871. Wood engraving by the Dalziels, 9.3 cm high by 13.6 cm wide.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.].

Passage Illustrated

[The jailers] led him through a paved room under the court, where some prisoners were waiting till their turns came, and others were talking to their friends, who crowded round a grate which looked into the open yard. There was nobody there to speak to him; but, as he passed, the prisoners fell back to render him more visible to the people who were clinging to the bars: and they assailed him with opprobrious names, and screeched and hissed. He shook his fist, and would have spat upon them; but his conductors hurried him on, through a gloomy passage lighted by a few dim lamps, into the interior of the prison.

Here, he was searched, that he might not have about him the means of anticipating the law; this ceremony performed, they led him to one of the condemned cells, and left him there — alone.

He sat down on a stone bench opposite the door, which served for seat and bedstead; and casting his blood-shot eyes upon the ground, tried to collect his thoughts. After awhile, he began to remember a few disjointed fragments of what the judge had said: though it had seemed to him, at the time, that he could not hear a word. These gradually fell into their proper places, and by degrees suggested more: so that in a little time he had the whole, almost as it was delivered. To be hanged by the neck, till he was dead — that was the end. To be hanged by the neck till he was dead.

As it came on very dark, he began to think of all the men he had known who had died upon the scaffold; some of them through his means. They rose up, in such quick succession, that he could hardly count them.

[Chapter 52, "Fagin's Last Night Alive," p. 200]

Commentary: The Many Treatments of Fagin in the Condemned Cell

In his introduction to the Waverley edition of the novel in 1912, A. C. Benson observes the novel's good people, the Maylies and Mr. Brownlow in particular, are "intolerably uninteresting," and that even the heroic Oliver for most of the story "is a mere guileless and stainless phantom" (xi).Even the brutal Sikes is more interesting, in his sheer will to survive, no matter what the costs to others. But, best of all is Fagin, a criminal mastermind who nevertheless seems to care about the boys in his charge, although he would never admit to the weakness of caring for anybody but himself. Like Nancy, Fagin has depth, so that it is not his badness that renders him fascinating, but his relative complexity. As Lucinda Dickens Hawksley remarks of Dickens's fascination with the complex and subtle master-thief,

he portrays his villain as an unscrupulous and deeply unattractive individual, yet also has great compassion for Fagin as he awaits his death by hanging in the condemned cell of Newgate Prison. [36]

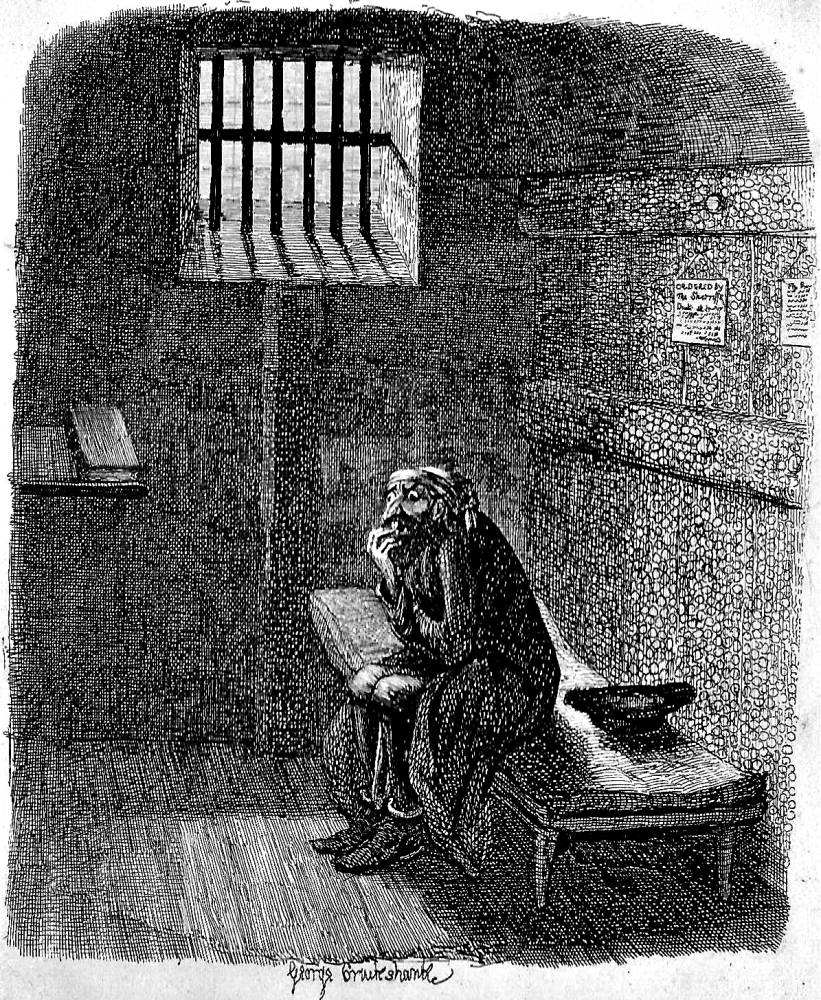

Our interest in Fagin rises to a crescendo in Chapter 52. Although other illustrators have shown the condemned Fagin awaiting execution at Newgate, Cruikshank's treatment of both the prisoner and the physical setting remains the locus classicus because of the artist's conveying with effective economy the starkness of the chamber and the psychological unravelling of the inmate. Aware that one of the sordid, lower-class villains — Sikes, or Fagin — would probably finish the novel in Newgate Prison, Cruikshank did multiple studies of both criminals in the condemned cell. Eventually, of course, once he had read the concluding chapters in manuscript, he learned that the solitary prisoner facing execution would be Fagin; however, he struggled to find just the right pose and facial expression to convey the internal conflict of the condemned man who, in Dickens's text, experiences a great range of emotions in contemplating his own impending death.

Cruikshank's treatment of the subject of the condemned criminal awaiting execution has, of course, become iconic, influencing numerous later artists' depictions of such situations, and perhaps even influencing illustrators of Great Expectations in the scene in which Magwitch dies in prison after killing Compeyson on the Thames, although, as illustrator John McLenan notes, Magwitch does not die alone and unfriended in The placid look at the white ceiling came back, and passed away, and his head dropped quietly on his breast in Harper's Weekly 5 (27 July 1861): 447. In fact, a merciful Providence permits Magwitch, a fundamentally decent man, to cheat the gallows by succumbing to his inguries. While the 1861 illustration shows Magwitch at peace, facing death with his "dear boy" beside him, the key word in the passage realized in the Mahoney plate is "— alone" (200).

Although the 1870s Household Edition illustrator James Mahoney depicts Fagin in his last hours, his treatment of his subject clearly subsumes in a realistic manner the slightly more caricatural treatment of Cruikshank's original. Having depicted Fagin with his open cash-box at the very beginning of his sequence of character studies, Sol Eytinge had no opportunity to revisit the character, and, perhaps as a consequence of Cruikshank's memorable plate, no inclination to attempt to outdo Dickens's original illustrator. Mahoney, on the other hand, obviously felt that he could recreate the highly dramatic moment in a more realistic manner in the Newgate cell as He sat down on a stone bench opposite the door pays homage to George Cruikshank's original conception, although Mahoney as a realist has eliminated the theatrical properties and gestures to focus on Fagin's tortured inner state. In fact, Mahoney has realised an earlier passage when, having just received his death sentence, Fagin is searched before entering one of the condemned cells. Although manacled about the ankles like his counterpart in the 1838 engraving, Mahoney's figure rests upon a stone bench rather than a cot. Mahoney includes neither the bars nor bible from the Cruikshank plate, and dispenses with the two embedded, hand-written notes (from the Sheriff, and therefore presumably directed towards inmates) above the prisoner. The only ornamentation in Mahoney's wood-engraving is the initials of several former occupants of the cell (upper left). There is neither table, nor Bible, nor barred window: his focus is entirely upon the pathetic criminal contemplating his own imminent death.

Whereas Cruikshank provides visual continuity by dressing Fagin in much the same clothing throughout, and consistently emphasizes his bulging eyes, here he is neither in motion or in company; he becomes in his isolation a pitiable figure worthy of some compassion. After all, although a career criminal and receiver of stolen goods, Fagin is hardly guilty of violent crimes so that, unlike Sikes, the death of Fagin seems disproportionate to his actions. In fact, only his inciting Sikes to murder Nancy can excuse Fain's sentence, which otherwise would be transportation, the fate that has attended the other members of his pickpocketing crew. Mahoney seems to have avoided depicting Sikes and other gang members in these later chapters, depicting a Sikes without either his signature white hat or dog in the rooftop scene, And creeping over the tiles, looked over the low parapet, putting this scene of the criminal mastermind facing execution on the morrow as the final plate and climax of his series of twenty-eight, his bandaged head (a reminder of his having been assaulted) and shrunken posture rendering him pitiable, if not completely sympathetic. To this ignominious end has the master manipulator at last come.

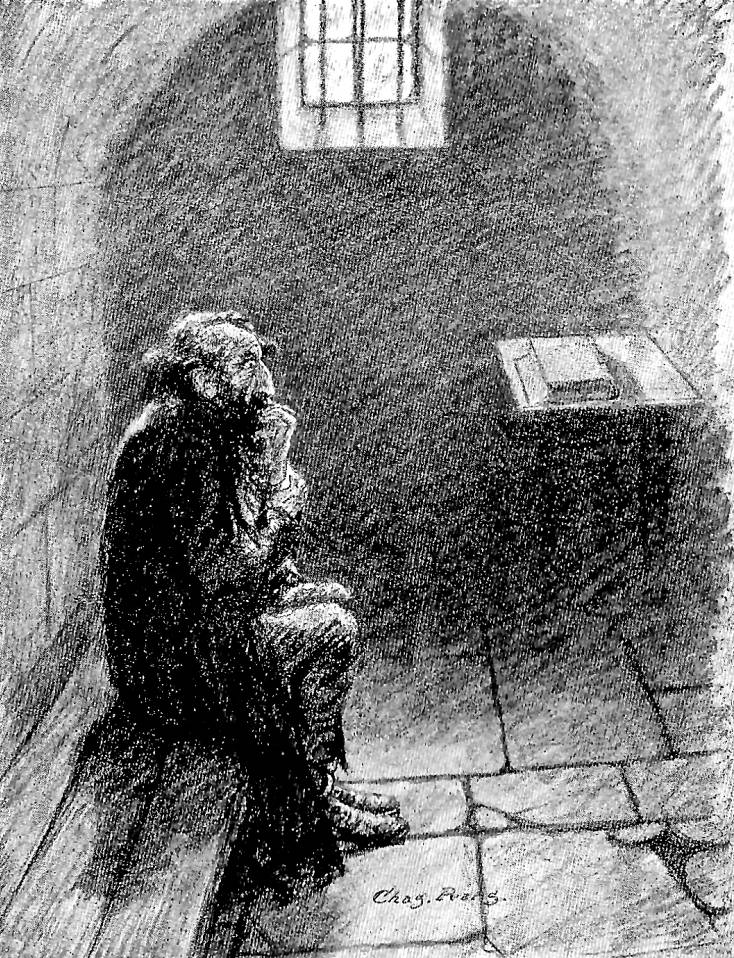

Again focussing on the figure of the condemned prisoner for his plate for Chapter 52, Harry Furniss in his 1910 lithographic series depicts Fagin as manacled at wrists and ankles, staring vacantly ahead with eyes that glow in the darkness of the cell, whose bars are reflected on the floor in Fagin in the Condemned Cell. The shading of the gaunt figure and strong lines delineating his clothing and beard suggest a pent-up energy. As he stares at the reader, Fagin is an enigma, for neither remorse nor reflection is immediately apparent on his savage features. He is alienated, although still dominating the page, but now bereft of associates and subordinates to do his bidding. His eyes shining "with a terrible light," Fagin in the Furniss illustration is both a haunted and a haunting presence, drawn with neither sentiment nor humour, but with smouldering intensity.

As Tony Lunch notes, Dickens had already employed Newgate as a setting in "A Visit to Newgate," the last of the "Scenes" section of Sketches by Boz, an essay especially written for the first collected edition of 1836. Dickens therein evokes the probable thoughts and feelings of three actual condemned prisoners: Robert Swan, convicted of armed robbery and subsequently reprieved, and two homosexuals, John Smith and John Pratt, who were hanged on the prison grounds on 27 November 1835. In novels after Oliver Twist, Dickens returned to Newgate, but only once to visit an inmate under sentence of death, Abel Magwitch in Great Expectations; however, whereas Fagin suffers execution, Magwitch cheats the system by succumbing to his injuries. "The Central Criminal Court — known as the Old Bailey — now cover the site of Newgate Prison" (Lynch 137), occupying Ludgate Hill.

Positioned in prominently, centre bottom, in the 1846 monthly wrapper is a second, re-thought version of Cruikshank's Fagin, contemplating his own death and — like Shakespeare's Richard the Third — the deaths of those who previously occupied the same cell, including some whose arrests he engineered. Beside him on the stone bench is his hat, seen in Cruikshank's earlier representations of Fagin. This representation appears to have influenced Mahoney's conception of the scene, for, although darkness is now beginning to engulf the cell, all is otherwise much the same as in the wrapper's vignette, including the hat on the bench, left, nearly lost in the darkness — and Mahoney does not show the barred window, or even its ominous shadow. The heavily shackled Fagin, however, is far more introspective and withdrawn in Mahoney's realisation. In neither the 1846 vignette nor the 1871 Household Edition study is there a Bible in the cell, nor even a table, as if Fagin is without even these simple objects for contemplation, and cannot avail himself of religious consolation, should he experience a last-minute spirituality. Since only after the moment captioned do the "Venerable men of his own persuasion . . . come to pray beside him" (200), the book is not likely a Hebrew Bible left by the rabbis whom Fagin subsequently dismisses "with curses." Furniss's version of this same scene, Fagin in the Condemned Cell, focussing on the glowing eyes of the prisoner, already "a snared beast" (202, Household Edition) offers only minimal details of the cell: the shadow of the bars and the end of the stone bench. The condemned man is trussed up like a turkey, manacled at wrists and ankles, as in the Mahoney illustration. Although Charles Pears' figure (Waverley Edition, 1915) is likewise manacled, in the pencil drawing one is struck by Fagin's calm introspection — and his balding head, implying both age and thoughtfulness — the more sensitive treatment of Fagin here may well reflect Mahoney's appreciation of the charges of anti-Semitism that the text and its illustrations initially provoked. Strangely, although Mahoney has included the Bible on the table from earlier versions, Pears has made the bench into one of wooden planks, although Dickens's text specifies that it is "stone."

None of these illustrators, however, has deviated from the theme of the cheerless, minimally furnished cell that is the scene of the prisoner's last night as a living being. In contrast, historical pictures show the "Upper Condemned Cell" at Newgate, as in the Thomson painting of the preparations for the 1824 execution of forger Henry Fauntleroy, a partner in the bank Marsh, Sibbald and Co., as much larger and better lit. Even Luker's The Condemned Cell (1891) shows the cell as at least twice as wide, with two barred windows. However, a rare photograph dating from the 1890s shows a cell remarkably like Fagin's, although dating (apparently) from after the reforms of 1858, which occurred as a result of the political agitation of Elizabeth Fry:

It was in 1858 that the interior of Newgate Prison was re-built, on the single-cell system. Near the window of the cell shown above are the water-tank and basin; and in the right-hand corner is the bedding, neatly rolled up; on the shelf are the prisoner's Bible, prayer-book, plate, and mug, while in the foreground are his stool and the corner of the table. [http://www.peterberthoud.co.uk/2012/05/inside-newgate-prison/]

As opposed to the fictional Fagin, some 1,169 real prisoners met their deaths on the grounds of Newgate, one of the most celebrated of these inmates being Ikey Solomon (1787-1850), upon whom Dickens may have based the character of Fagin — although Solomon, a transported felon, died in prison in Hobart, Tasmania, and not in Newgate. Even though as a result of the public campaign waged by such progressives as Charles Dickens (who detested such atavistic public exercises for the emotional and psychological damage they did to Victorian society as a whole), authorities discontinued public executions after 26 May 1868, private executions continued to be carried out on a gallows inside the prison walls. Closed in 1902, Newgate Prison was demolished in 1904. The Central Criminal Court (also known as "The Old Bailey" after the street on which it stands) now stands upon its site.

Relevant Illustrations from the serial edition (1838), 1846 serial wrapper (detail), Charles Dickens Library Edition (1910), and Waverley Edition (1912)

Left: George Cruikshank's initial depiction of Fagin in Newgate, Fagin in the Condemned Cell (1838). Right: Charles Pears' Fagin (1912). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Left: George Cruikshank's depiction of Fagin in prison, detail from the wrapper (1846), bottom centre. Right: Harry Furniss's Charles Dickens Library Edition illustration Fagin in the Condemned Cell (1910). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

References

Benson, A. C. "Introduction" to Charles Dickens's The Adventures of Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress. Illustrated byCharles Pears. London: Waverley, 1912. Pp. v-xiv.

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Cohen, Jane Rabb. "George Cruikshank." Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980. Pp. 15-38.

Darley, Felix Octavius Carr. Character Sketches from Dickens. Philadelphia: Porter and Coates, 1888.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Adventures of Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress. Illustrated byGeorge Cruikshank. London: Bradbury and Evans; Chapman and Hall, 1846.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Household Edition. 55 vols. Il. F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. New York: Sheldon and Co., 1865.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Diamond Edition. 14 vols. Il. Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

Dickens, Charles. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Household Edition. Illustrated byJames Mahoney. London: Chapman and Hall, 1871.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. The Annotated Dickens. Ed. Edward Guiliano and Philip Collins. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1986. Vol. 1. Pp. 534-823.

Dickens, Charles. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. Charles Dickens Library Edition. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 3.

Dickens, Charles. The Adventures of Oliver Twist. Works of Charles Dickens. The WaverleyEdition. Illustrated by Charles Pears. London: Waverley, 1912.

Dickens Hawksley, Lucinda. Dickens' Bicentenary 1812-2012: Charles Dickens. San Rafael, California: Insight, 2011.

Forster, John. "Oliver Twist 1838." The Life of Charles Dickens. Ed. B. W. Matz. The Memorial Edition. 2 vols. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1911. Vol. 1, book 2, chapter 3. Pp. 91-99.

Berthoud, Peter. "A Cell in Newgate Prison." Accessed 27 December 2014. http://www.peterberthoud.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/Newgate-4.jpg.

Kitton, Frederic G. "George Cruikshank." Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. 1899. Rpt. Honolulu: U. Press of the Pacific, 2004. Pp. 1-28.

Luker, W., Jr. "Newgate — The Condemned Cell," in W. J. Loftie, London City — Its History, Streets, Traffice, Buildings, People, 1891. http://www.ph.ucla.edu/epi/snow/1859map/newgate_prison_a10.html

Lynch, Tony. "Newgate Prison, London." Dickens's England: An A-Z Tour of the Real and Imagined Locations. London: Batsford, 2012. Pp. 137-138.

McLenan, John, illustrator. "The placid look at the white ceiling came back, and passed away, and his head dropped quietly on his breast." Charles Dickens's Great Expectations. Harper's Weekly 5: 27 July 1861: 447.

Last modified 3 January 2015