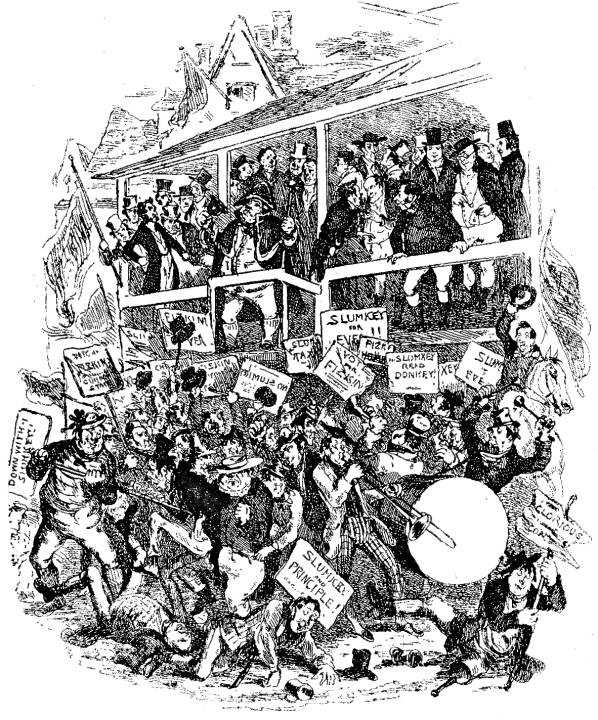

"He has come out," said little Mr. Perker, greatly excited; the more so as their position did not enable them to see what was going forward. by Phiz (Hablot K. Browne). Household Edition (1874) of Dickens's Pickwick Papers, Engraved by one of the Dalziels. Chapter XIII, “Some Account of Eatanswill; of the state of Parties therein; and of the Election of a Member, to serve in Parliament for that ancient, loyal, and patriotic Borough,” page 81. The illustration is 11.3 cm high by 14.4 cm wide (4 ⅜ by 5 ⅝ inches), framed. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Passage Illustrated: A Sharply Contested By-election

‘Nothing has been left undone, my dear sir — nothing whatever. There are twenty washed men at the street door for you to shake hands with; and six children in arms that you’re to pat on the head, and inquire the age of; be particular about the children, my dear sir — it has always a great effect, that sort of thing."

"I’ll take care," said the Honourable Samuel Slumkey.

"And, perhaps, my dear Sir," said the cautious little man, "perhaps if you could — I don’t mean to say it’s indispensable — but if you could manage to kiss one of 'em, it would produce a very great impression on the crowd."

"Wouldn't it have as good an effect if the proposer or seconder did that?" said the Honourable Samuel Slumkey.

"Why, I am afraid it wouldn't," replied the agent; "if it were done by yourself, my dear Sir, I think it would make you very popular."

"Very well," said the Honourable Samuel Slumkey, with a resigned air, "then it must be done. That's all."

"Arrange the procession," cried the twenty committee-men.

Amidst the cheers of the assembled throng, the band, and the constables, and the committee-men, and the voters, and the horsemen, and the carriages, took their places — each of the two-horse vehicles being closely packed with as many gentlemen as could manage to stand upright in it; and that assigned to Mr. Perker, containing Mr. Pickwick, Mr. Tupman, Mr. Snodgrass, and about half a dozen of the committee besides.

There was a moment of awful suspense as the procession waited for the Honourable Samuel Slumkey to step into his carriage. Suddenly the crowd set up a great cheering.

"He has come out," said little Mr. Perker, greatly excited; the more so as their position did not enable them to see what was going forward.

Another cheer, much louder.

"He has shaken hands with the men," cried the little agent.

Another cheer, far more vehement.

"He has patted the babies on the head," said Mr. Perker, trembling with anxiety.

A roar of applause that rent the air.

"He has kissed one of 'em!" exclaimed the delighted little man.

A second roar.

"He has kissed another," gasped the excited manager.

A third roar.

"He's kissing 'em all!’" screamed the enthusiastic little gentleman, and hailed by the deafening shouts of the multitude, the procession moved on. [Chapter XIII, “Some Account of Eatanswill; of the state of Parties therein; and of the Election of a Member, to serve in Parliament for that ancient, loyal, and patriotic Borough,” page 86 in the Chapman & Hall edition, page 80 in the Harper & Brothers' edition]

TransAtlantic Reworkings of Phiz'sthe August 1836 Steel-engraving

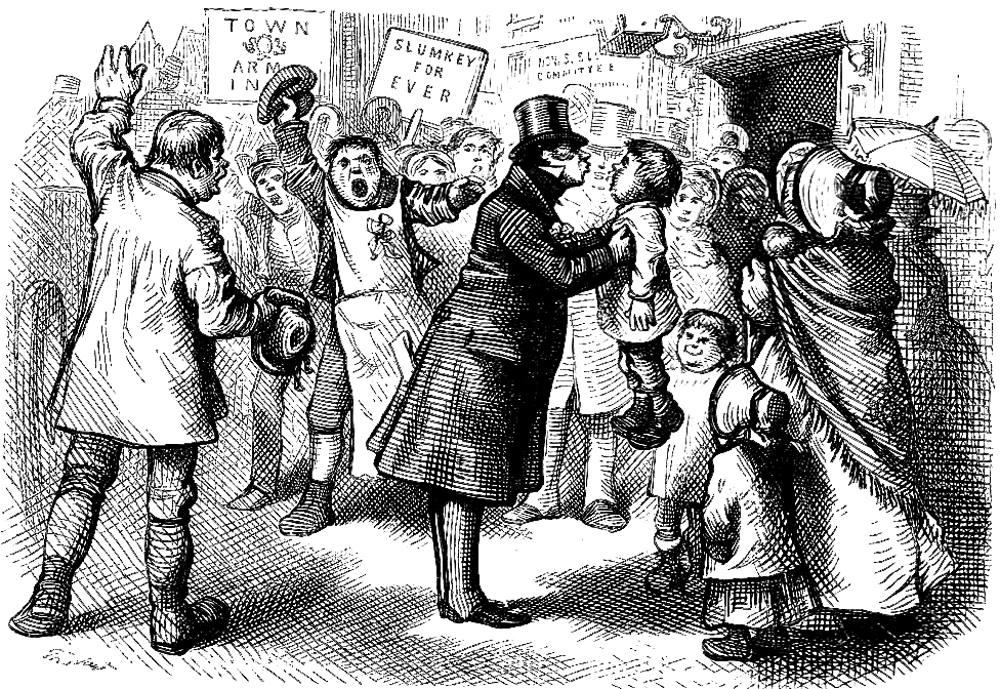

Left: The Election at Eatanswill — the August 1836 illustration by Phiz. Right: Thomas Nast's 1873 illustration, "He's kissing 'em all!" (1873).

Although the nature of elections in support of British parliamentary democracy must have become somewhat less adversarial, corrupt, and raucous between 1834 (the date of the Sudbury by-election covered by young reporter Charles Dickens) and the 1870s, Phiz merely reprised the 1836 engraving The Election at Eatanswill (Part 5: August 1836) for his 1873 woodcut for the British Household Edition. However, instead of celebrating the Hogarthian mob-mentality of the contest between the Buffs (Whigs) and Blues (Tories), Phiz like his American counterpart, Thomas Nast, chose to focus instead on the candidates' patting children on their heads and kissing babies to win their mothers' goodwill and their fathers' votes in "He has come out," said little Mr. Perker, greatly excited; the more so as to their position did not enable them to see what was going forward. [Page 81] and "He's kissing 'em all!" [Page 81] respectively. Whereas Phiz's Slumkey (on the sign to the left, "SLUM KEY") seems to have some tender regard for the infant he is about to kiss (centre), Nast's great-coated politician holds aloft a frightened toddler. The comparable juxtaposition of the candidates, the crowd — more raucous in the American version, more benign in the British — as a backdrop, and in particular an almost identical positioning of the sign "Slumkey for ever" (left rear) suggests that the British artist was copying the American's work. The instigator of this electoral strategy for the well-dressed Samuel Slumkey is none other than attorney Perker, who had negotiated earlier with Jingle at The White Hart in the Borough (Southwark) on behalf of Mr. Wardle. We may assume that, since neither Pickwick nor his comrades appear in either illustration, the perspective from which we see each scene is theirs.

Commentary: A Satire on British Parliamentary Democracy

Apparently a politician's kissing babies was then not quite so great a cliché. The presence of ten young women, none of whom could vote even in the 1870s, at first glance would seem an anomaly to a modern reader; however, as Perker has explained to Pickwick earlier in the election chapter, the way to securing the votes of the male electors lay through their wives and children — indeed, the Honourable Slumkey's Tory re-election committee has already bribed forty-five women with green parasols. Now Slumkey must make the ultimate political gesture: kiss every infant presented to him. And Phiz has given us seven infants, four young children, and ten young women, whereas the adult males in the crowd near The Town Arms (for which Nast has incorporated the sign in his design) number a mere nine, exclusive of the child-patting candidate (centre) himself. Processional signs in both Household Edition illustrations proclaim, "Slumkey forever," although Phiz's sign is missing the "for" (upper left) and the name "Slumkey" has been divided, with humorous effect. The shaggy hairstyles, disreputable hats, smock-frocks and aprons of "bully-boy" Slumkey adherents (left) in Nast's illustration together with the prominence of the sign "Town Arms" in the background (left) recalls the suborned bar-maid's spiking with laudanum the brandy-and-water of fourteen unpolled electors in the previous Eatanswill election, an anecdote that Sam Weller recounted to Pickwick before breakfast that day.

Although Phiz sided with young Dickens, who was very much a Radical in the early 1830s, supporting the Great Reform Bill of Lord John Russell in 1832, Nast was a virulent opponent of governmental corruption, the New York Democratic party machine, and the Tammany Hall political clique, as well as an anti-slavery proponent (and therefore a staunch Republican). Consequently, both Household Edition illustrations take a dim view of traditional political shenanigans and "dirty tricks."

Related Material

- The complete list of illustrations by Seymour and Phiz for the original edition

- An introduction to the Household Edition (1871-79)

Other artists who illustrated this work, 1836-1910

- Robert Seymour (1836)

- Thomas Onwhyn (1837)

- Felix Octavius Carr Darley (1861)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr. (1867)

- Thomas Nast (1873)

- Harry Furniss (1910)

- Clayton J. Clarke's Extra Illustrations for Player's Cigarettes (1910)

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the images, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Cohen, Jane Rabb. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Columbus: Ohio State U. P., 1980.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File and Checkmark Books, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Robert Seymour, Robert Buss, and Phiz. London: Chapman and Hall, November 1837. With 32 additional illustrations by Thomas Onwhyn (London: E. Grattan, April-November 1837).

_____. Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. 14 vols. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. Vol. 1.

_______. Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Thomas Nast. The Household Edition. 16 vols. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1873. Vol. 4.

_______. Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ('Phiz'). The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1874. Vol. 6.

_______. Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 2.

Guiliano, Edward, and Philip Collins, eds. The Annotated Dickens.2 vols. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1986. Vol. I.

Hammerton, J. A. The Dickens Picture-Book. London: Educational Book Co., 1910.

Johnannsen, Albert. "The Posthumous Papers of The Pickwick Club." Phiz Illustrations from the Novels of Charles Dickens. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; Toronto: The University of Toronto Press, 1956. Pp. 1-74.

Kitton, Frederic G. Dickens and His Illustrators. 1899. Rpt. Honolulu: U. Press of the Pacific, 2004.

Steig, Michael. Chapter 2. "The Beginnings of 'Phiz': Pickwick, Nickleby, and the Emergence from Caricature." Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U. P., 1978. Pp. 24-50.

Created 9 March 2012

Last modified 8 April 2024