Introduction

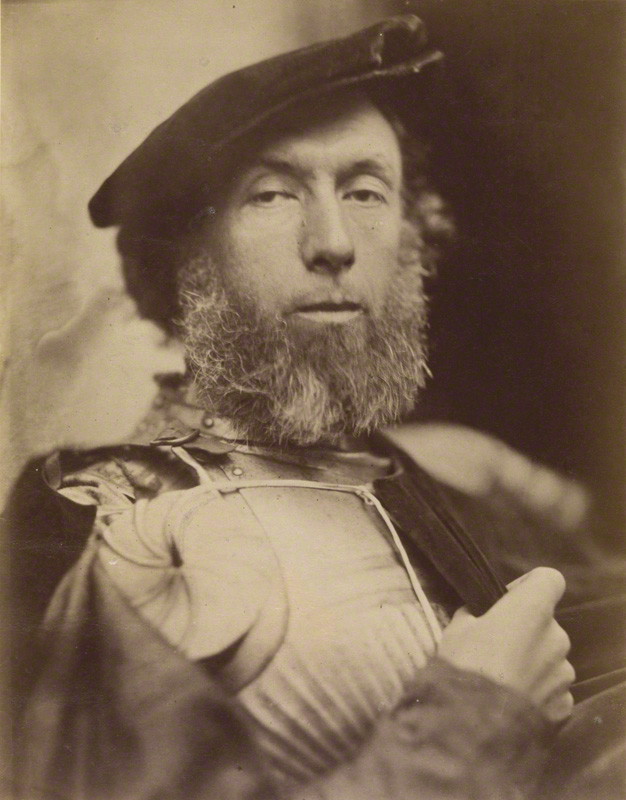

Frederick Richard Pickersgill. Photograph by David Wilkie Wynfield. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Pickersgill’s work as a painter working in the historical style is generally well-known. His activities as an illustrator, on the other hand, have been undervalued. His book designs are briefly discussed by Goldman (1996, 2004, pp. 211–13) and Reid (1928, pp. 248–51), and the artist is listed in most reference books on Victorian illustration; however, his printed work has never been the subject of sustained investigation.

Born in 1820, Pickersgill’s professional life spanned several changes in graphic style. In the twenties, the dominant idiom was the comic grotesque of Cruikshank; in the fifties and sixties the centre stage was taken by the poetic naturalism of Millais, Pinwell, and Sandys; and Pickersgill was still alive in the 1890s, when the art nouveau of Beardsley and Ricketts was in fashion. He did not engage with any of these, even if his illustrations appeared in conjunction with artists of the Sixties. His book-images can be understood, however, as a combination of several overlapping and converging tendencies.

One influence was the pictorial idiom he deployed in his painting, and like many painter/illustrators of his time he routinely transferred the visual language of fine art to the small frame of the printed page. The compositional devices that characterize his work in oil and watercolour are cleverly used in black and white, and Pickersgill’s illustrations can be read as paintings in print.

Another source was the ‘outline style’. This was figured in two varieties: the British version, created by Flaxman in imitation of Attic vase-painting; and the ‘Germanic’ outlines by Retzsch, which took the form of a series of literary picture-books. These artists were popular in the 1830s and '40s, and Pickersgill was influenced by both of them. He was also responsive to Schnorr von Carolsfeld’s Bilderbibel or Picture Bible, which appeared in Germany and England in the period 1856–60; and to the art of Rethel, notably his designs for The Dance of Death (Brothers Dalziel, p. 52).

Often described as a ‘Germanic artist’ and always as a classicist, Pickersgill absorbed the lessons of Schnorr, Rethel and Retzsch along with the frieze-like design of Flaxman; like many of his period, he produced an illustrative style which is essentially a hybrid, and reflects the cultural interchange between England and Germany in the early years of Victoria’s reign. The end result is a type of plangent drawing in which the figures are carefully modelled in dramatic and telling situations while also having a clean and efficient outline.

Permeated by the imagery of idealized heroes and mythology, Pickersgill’s approach to illustration is accordingly suited to dramatic subjects in the manner of ‘high art’. He was a painter of elevated subjects, and his graphic designs are generally pitched at the same level, usually in service of the Bible, history, and epic verse. He formed a close professional relationship with the Dalziels, producing memorable work in the form of the rare Six Compositions from the Life of Christ (1850) and in the monumental Bible Gallery of 1880 (dated 1881). Other designs, this time for literature, appeared in Willmott’s Poets of the Nineteenth Century (1857), the same editor’s English Sacred Poetry (1862), and in other books of verse such as Montgomery’s Poems (1860) and Moore’s Lalla Rookh (1860).

Pickersgill’s designs for all of these commissions are efficient illustrations: respectful of their texts, which are shown with close attention to nuance and implication, they are also well-crafted examples of drawing on wood. Undeserving of their neglect, they represent a significant body of work which, as Goldman explains, is ‘underrated’, ‘warrants [further] exploration’ (p. 212) and would form an ideal subject for a doctoral thesis or a detailed monograph.

Related Material

Works Cited

Goldman, Paul. Victorian Illustration. Aldershot: Scolar, 1996; Lund Humphries, 2004.

Reid, Forrest. Illustrators of the Sixties. London: Faber & Gwyer, 1928; New York: Dover, 1970.

The Brothers Dalziel. A Record of Work, 1840–1890. 1901; reprint, with a Foreword by Graham Reynolds. London: Batsford, 1978.

Last modified 10 January 2013