Sandys was essentially an illustrator of magazines. All but four of his images appeared in periodicals, or were intended for periodicals. With the exception of a couple of designs on steel for his book-work the medium was wood-engraving, and Sandys prided himself on being a ‘wood-cut artist’. Unlike many of his contemporaries he embraced the technical difficulties involved in the process, and set out to create a distinctive body of imagery that clearly displayed the technical characteristics of a ‘drawing on wood’. Signing his work with a monogram that echoes Dürer’s, Sandys invokes the spirit of the German master, and presents himself (with characteristic immodesty) as a modern-day equivalent.

He produced only twenty five illustrations on wood and like Rossetti, who drew only ten, ‘made a great impression [through] a very small oeuvre (Ray, p.107). Each of these is a monumental design in black and white displaying the intricate play on light and dark that is central to the effects of engraving, but also has the finish and complexity of a work on canvas. Though complicated, his illustrative work is tightly focused on a few themes; as T. Earle Welby explains, his art embodies ‘three or four emotional motifs’ (p.79).

His main interest is psychological drama in which a well-defined character, usually realized in the form of a large central figure, sometimes male, but predominantly female, experiences some emotional extreme. This ranges from intense agitation to focused introspection: on the one side is fear, and on the other disappointment and frustration. It also includes an unusually frank representation of sexual arousal as well as a reflection on the despair of grief. The effect, Paul Goldman remarks, is always ‘febrile’ (p.51).

Fearfulness and agitation are embodied in The Portent, Manoli and Jacob hears the voice of the Lord, all of which deploy the melodramatic visual language of gesture and distorted facial expressions. Showing, in each case, a moment of crisis, the illustrations usually distort the characters’ bodies. In Manoli, the terrified woman’s throat is extended to a muscular extreme, with the veins clearly marked, and in Jacob the character crouches into a near-impossible stance, penetrating the viewer’s space.

Extremes of despair and fear similarly feature in The Waiting Time (in which an unemployed weaver awaits her own death through starvation), and again in The Sailor’s Bride, where the grieving characters are brought together in an expressionistic bundle of interlocked limbs. Death is a central theme, sometimes as horrific or terrifying. In Yet once more on the organ play the raised torso is racked with pain, and in Amor Mundi the female lover’s body is seen in its future state, juxtaposing her voluptuous figure in life with what she will become after death. Once again, the body becomes the site of expression.

Left to right: (a) The Little Mourner. (b) Life's Journey. (c) The Old Chartist

In another series, however, Sandys focuses on quieter emotions. The Little Mourner is an unsentimental image of a girl stoically clearing snow from her parents’ grave, and in Life’s Journey and The Old Chartist the emphasis is on reflection, focusing on memories and the passage of time. These illustrations deploy the same distortions of gesture, presenting the same malleable bodies, but they also point to his capacity to deploy the pathetic fallacy, using backgrounds to suggest mental states. In The Little Mourner, for instance, the snowy background is an objective correlative of her emotional state, and in Life’s Journey and The Old Chartist the intense detailing of the idyllic English countryside suggests both the complexity of life and the intricate, Romantic relationship between human experience and nature.

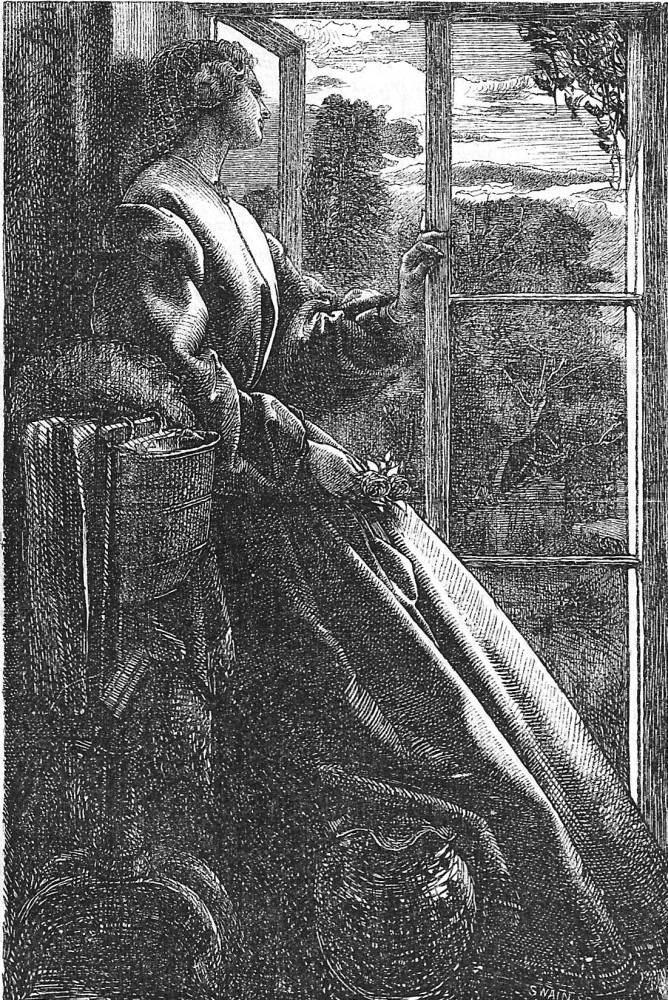

Left to right: (a) If he would come to-day. (b) From my Window.

This charting of complex emotions finds another expression in his treatment of love. Sandys pictures romance not as fulfilment, but as frustration. In If, an illustration for a poem by Christina Rossetti, he shows the disappointed girl chewing on her hair and tugging on blades of grass – small signs of a complex feeling. The fading of hope is similarly signalled in From my window, here suggested by the fading of the light and the woman’s weary gesture, with her head resting on the window frame and her other hand about to open the casement the moment her lover arrives.

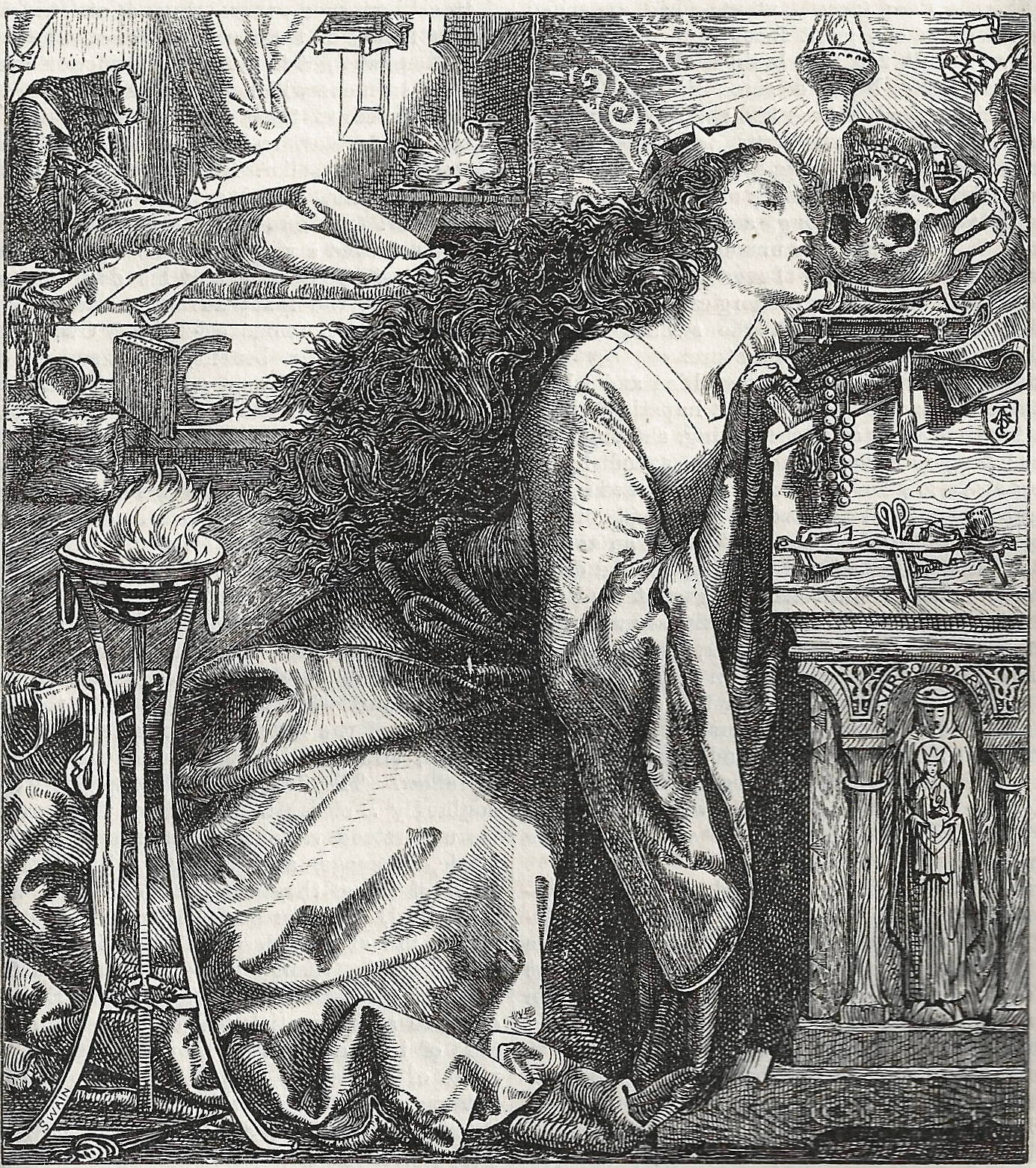

Left to right: (a) Rosamund. (b) Danaë in the Brazen Chamber.

Several of his designs are erotic subjects, in each case dealing with sexuality in a psychological manner. In Amor Mundi the multiple images of intertwining forms suggests physical union, and in Danaë in the Brazen Chamber the character’s stance and expression as she combs her hair, is a surprisingly candid representation of sexual arousal. Others are even more challenging: in Rosamund and Yet once more upon the organ play sexuality and death are startlingly combined, and there are erotic undertones elsewhere in the illustrations.

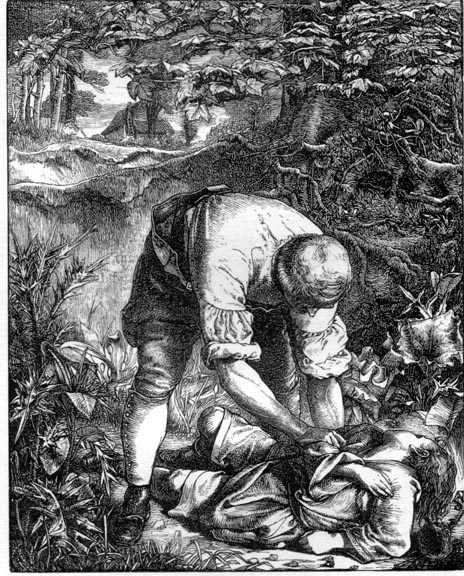

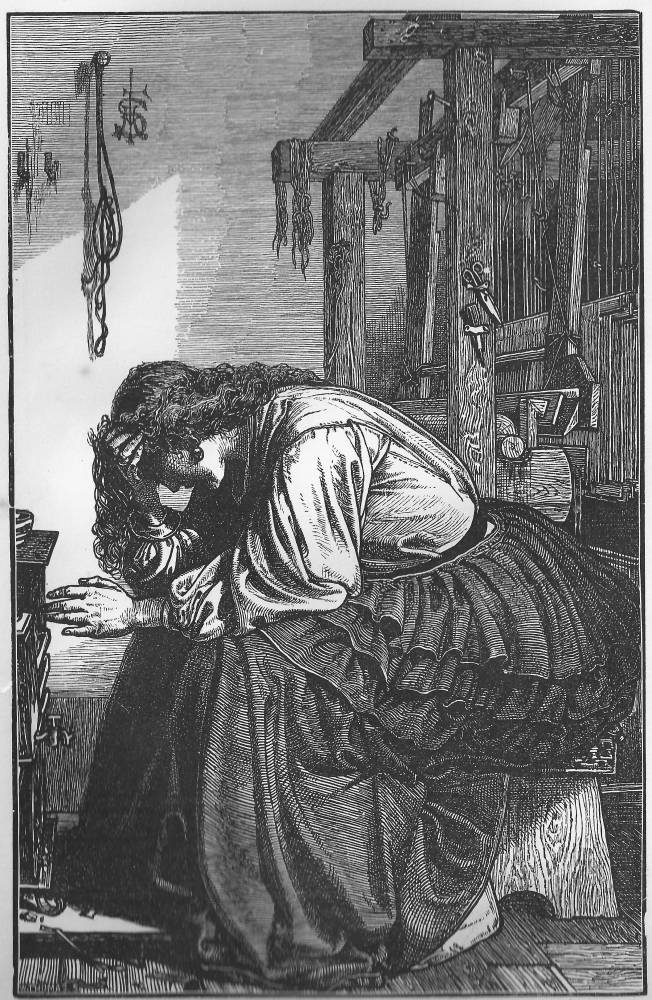

Left to right: (a) Harold Harfagr. (b) The Waiting Time.

The illustrations are generally figured as rich fields with many ambiguities and it is important to register not only the intense, claustrophobic narrowness of his art, but its ambition as well. Though concerned with the grand themes of love and death, Sandys also veers between dreamy escapism in Harold Harfagr and engagement with contemporary life, partly in his use of modern settings, but also in the form of political commentaries in The Old Chartist and The Waiting Time.At once neo-classical and medievalist, Modern and Romantic, Sandys deploys a number of styles in order to explore his characteristic themes, and his art can sometimes appear disparate.

There are nevertheless at least two unifying threads: one is the emphasis on draughtsmanship, with each design being worked to an intense finish; and the other is a consistent tonality. The ambience, whatever the subject or style, is always the same. In The English Pre-Raphaelite Painters (1905) Percy Bate argues that Sandys strikes a ‘Wagnerian note of the tragedy of heroes, almost superhuman, elemental’ (p.57). Bate’s comments are apt and are especially applicable to the treatment of King Warwulfand Aegina. However, the tone of his work might better be described as melancholy; most of the faces are solemn and withdrawn, and the overall effect is one of portentous suffering informed with a sense of menace. Some of this was derived from Pre-Raphaelitism, and some from the morbidity of German wood-engraving, especially the example of Alfred Rethel and the melancholia of Dürer.

Last modified 15 July 2013