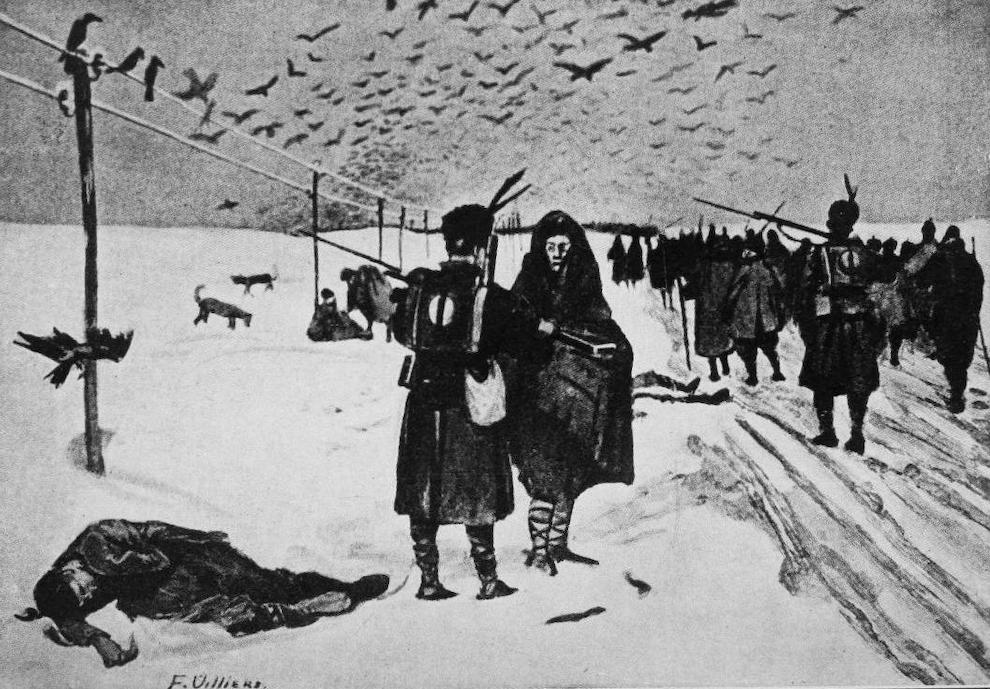

Winter Scene in the First Balkan War by Frederic Villiers. Winter 1877-78. Source: Villiers, facing p. 116. This is in Chapter VI, "The Black Death," showing the harrowing aftermath of the recent Battle of Plevna in the Russo-Turkish War. The Turks had been defeated, and, as Villiers himself explains in the passage below, here he bears witness to the march of the weakened Turkish prisoners through Rumania, across a bleak snowy plain, in the charge of their Russian captors. Some have fallen by the wayside, and those comrades who linger, intending to stoop to help, are turned back brusquely by the enemy guards. Countless birds and a few dogs wait to feed on the dead men's bodies.

Passage Illustrated

IN a short two years I had already been an eye-witness, at the age of twenty-six, to ten big battles and as many skirmishes, but this second battle of Plevna, which I have just described, was the biggest up to date, and stirred the world more than any of the other encounters. The most dramatic incident of that campaign to my mind, however, was the march of the Turkish defenders of the Plevna position after their surrender, which came as the result of the siege of that city by the reinforced Russian army. I have never seen a sight quite so sad in all my nomad life as the tramp of those wretched prisoners through Rumania into captivity in Russia during this cruel winter of 1877-8.

The Danube that year, before freezing, was full of floating ice, and the rapid current of the river pre[115/116]vented the passage of boats with food supplies, and all pontoons had been broken up by the floes. The Russian armies were practically starving. Then came the fall of the fortress and thousands of prisoners — extra mouths to feed — added to the difficulties of the Russian commissariat. The only thing for the Muscovites to do was to get the captured Turks as quickly as possible toward their food bases. Therefore, these men, half-starved on meager rations during the long siege, were pushed forward toward their goal, with hardly a scrap of food in their bodies for days on end. Not one third of these poor creatures who for so many months had held the huge masses of Russian soldiers at bay ever returned to their native land.

My companion, a doctor, and I were stowed away one morning with our furs in our sleigh — a sort of hencoop minus the top bars — with our baggage in the straw to serve as a seat. The mercury had fallen to some fifteen degrees below zero the night before, and our road, therefore, was too slippery to be the most desirable surface for sleighing. The result was that our conveyance would occasionally, to our consternation, run away with the horses when we came to a slant to left or right of the road, causing us to be always on the lookout for a collision with one of the many unsavory heaps of carrion by the roadside, on which hungry dogs were feeding. Dead horses and dying oxen now strewed our route, signs that we must be in the wake of some munition train. [116/117]

Presently we came up with a long line of wagons and sleighs loaded with shot and shell.

The morning was bitterly cold. Before us lay a vast plain of snow, broken only by the bare telegraph poles, which for miles traced our road through many a drift. The dead stillness of the plain under its white mantle was occasionally disturbed by the dull beating of the wings of carrion crows as the foul birds hovered over their prey. Soon they increased in number, making the leaden sky almost black. Then, afar off, breaking the horizon, a long dark line came slowly moving in caterpillar fashion over the snow toward us. It was a column of men marching. No Russian or Rumanian troops constituted it, or ere this we should have heard some cheerful song borne across the plain. I aroused my friend who had settled down in his furs and had fallen fast asleep.

"Look, what do you make of those fellows," said I. "Surely they must be Turkish prisoners. See the plumes of their Dorobantz guard waving as they advance."

"Yes," cried Sandwith, now thoroughly aroused and peering through his binocular. "I can see along with the escort Turkish officers, some on ponies, others on foot."

Behind tramped the men who had so long kept the Muscovites at bay around Plevna. How spiritless and broken they now looked as they trudged wearily along the road to their captivity! Half-starved, [117/118] almost dead with fatigue and the cruel cold, many with fever burning in their eyes, mere stalking bones and foul rags, came the brave troops who had made the fame of Osman Pasha. My companion, with the keen scent of the medical practitioner, sniffed the taint of smallpox and typhus lingering about them in the frosty air.

"For our lives, Villiers, we must get to windward of these poor fellows!" And we drove our sleigh to the left flank of the approaching column.

Many of these wretched creatures were even now falling out of the ranks and lying down to die. One had just thrown himself in the snow by the roadside — he could go no farther. A comrade, loath to leave him, followed and tried to persuade him to struggle once more to join the line. There was no answer; he had swooned or was dead. The ghastly line of living phantoms was trudging wearily forward. A soldier of the rear guard now came up. With the butt end of his musket he roughly pushed the living man back into the ranks; then with a brutal kick turned the head of the fallen Turk over in the snow. A wild, fixed stare met his gaze. The Turk was dead. The soldier shouldered his rifle and rejoined the guard.

Commentary

Villiers's account of the suffering of the defeated men is fully corroborated in Cassell's Illustrated History of the Russo-Turkish War (Ollier, Ch. XLV, especially 557ff.), in which several of the illustrations depict the Red Cross trucks mentioned here, the removal of the wounded etc. But, as Pat Hodgson says of another of Villiers's illustrations, his sketches were "unusually horrific in an age which shrank from realism in the depiction of war" (137). The one to which she refers had been redrawn for the Graphic by Godefroy Durand (1832-1896), but here Villiers has chosen one which seems entirely spontaneous, with his own signature clearly visible. Note that the volume is very sparcely illustrated (only four illustrations in more than 300 pages), so this haunting image of a corpse left behind as a prey to scavengers, and the plumed guard turning help away from him, would have been the one which he felt best conveyed the episode.

Villiers may have become rather a flamboyant, self-promotional personality, but there is no doubt of his sincerity, outrage and empathy here. The account also shows the danger in which he often put himself, this time of death by proximity to disease rather than to battle.

Scanned image, caption material, passage transcription, commentary and formatting by Jacqueline Banerjee. [You may use the image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned it, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Hodgson, Pat. The War Illustrators. New York: Macmillan, 1977. See especially pp. 24-25.

Ollier, Edmund. Illustrated History of the Russo-Turkish War Vol. I: From the Commencement of the War to the Fall of Plevna. London: Cassell, 1896. Google Books. Free ebook. Web. 13 April 2025.

Villiers, Frederic. Villiers: His Five Decades of Adventure. Vol. 1. New York and London: Harper, 1920. Internet Archive, from a copy in the University of California Libraries. Web. 14 April 2025.

Created 13 April 2025