Introduction

rt training in modern Britain is a well-established path. Students typically complete ‘A’ (Advanced) Levels or a vocational equivalent, followed by a Foundation Course and a degree at university. In Victorian Britain, on the other hand, the absence of state-sponsored provision meant that budding artists engaged with a variety of unregulated opportunities. This was a mixture of home-tuition, experience in a studio or workshop, formal art-training at one of the primary institutions and finally – and for the most able – professional studies at the Royal Academy.

Much of the work was conducted at home, usually under the direction of a drawing-master or established artist. The precocious Millais was coached by the historical painter E.H. Wehnert, and Richard Doyle was instructed by his father John, the satirical cartoonist known as ‘H. B’. (Engen, p.15). This emphasis on home-based learning is shared by artists of every sort; however, there are clear differences between the training of a painter, and the vocational education of those intending to become a graphic artist or illustrator.

In the early Victorian period illustrators and print-makers were principally trained in workshops where they learned the techniques of etching, lithography and wood-engraving. Regarded as artisans rather than artists, these graphic designers learned the technicalities of their trade, rather than the skills of draughtsmanship. A good example is Phiz, who was apprenticed to the engraver Finden (Lester, pp. 32–34), and Cruikshank was similarly trained in his father’s workshop. This educational process was sometimes systematically arranged, but was more typically a matter of a specific skill being taught ‘on the job’ and under the commercial pressure of completing a piece of work to a deadline.

The practicalities of the situation are exemplified by Doyle’s ‘training’ at Punch; familiar only with the discipline of working on paper, the artist had to learn how to draw on wood. The engraver Swain amusingly describes his attempts to instruct the ‘agitated youth’ who ‘literally dodged around’ (Engen, p. 46) the table as the exasperated technician tried to show him how to make decisive lines with a hard pencil, in reverse, on a smooth block painted in Chinese White. Such ad hoc arrangements are typical. Interestingly, there was no training whatever in the intellectual skills required to illustrate a literary text; this was assumed to be innate, whereas making the image itself was a craft-skill that had to be learned.

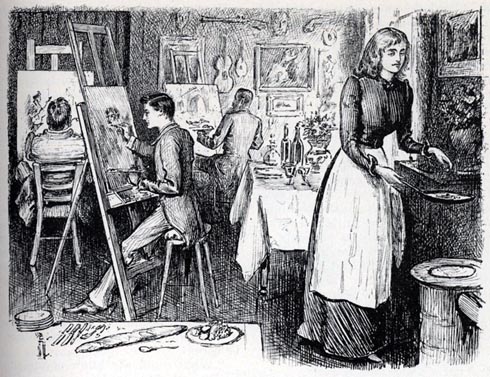

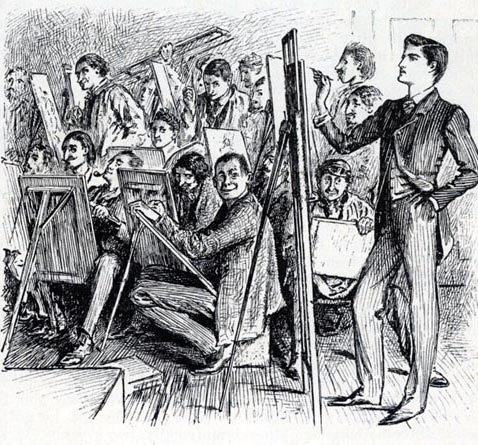

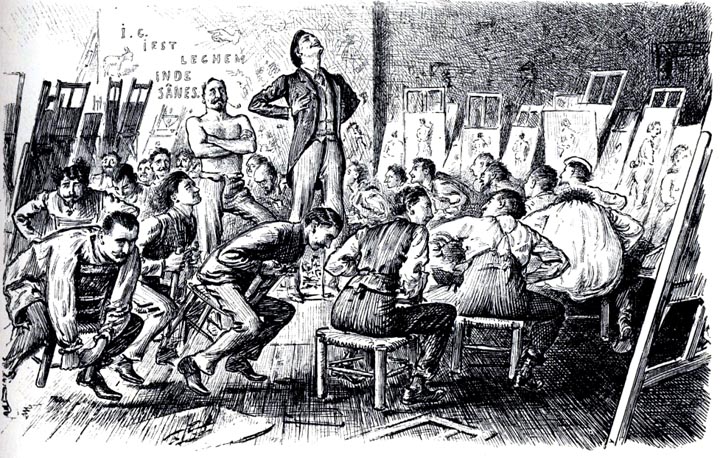

Du Maurier's portray of the life of art-students in Paris — Left to right: (a) Cuisine Bourgeoise en Bohème. (b) Av you seen my fahzere's ole shoes?". (c) The fox and the crow. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

For painters, on the other hand, the emphasis was placed on becoming literate in the language of art and all of its complications. Draughtsmanship, composition, copying from nature, modelling, perspective, the uses of colour and every other aspect of the profession were taught. Some older students trained in studios; the model was the French atelier system and several trained in France. Du Maurier famously trained at Gleyre’s, immortalising his experiences in Trilby (1895); Whistler also studied abroad. For younger students, though, the usual route was to gain entry to one of the London-based schools offering courses that prepared them for studies at the Royal Academy. The two pre-eminent institutions were Sass’s and Heatherley’s. These became rivals, and were in many ways quite dissimilar.

Sass’s: The Master and the Institution

The most famous of the London art-schools was Sass’s. This was regarded as an elite institution which set out to prepare (male) students for the Royal Academy just as Eton prepared its pupils for entry into Oxbridge. Set up by Henry Sass (1788–1844) in 1813, it moved in 1820 to No. 6, Charlotte Street, Bloomsbury. It was the first school to teach its students in any methodical way, and it occupies an important place in the development of Victorian art. Its list of alumni is certainly impressive. These premises were attended by Millais, Frith, Corbould and Deverell. Under the management of Stephen Cary (changing its name in 1842 to Cary’s), the school also trained Rossetti, Edward Lear, Simeon and Abraham Solomon, Henry Wallis and Braithwaite Martineau.

Sass had initially established his school because he was unable to make a living as a painter, producing works of only limited appeal. As contemporaries observed, it was somewhat ironic to observe that an artist who had failed to make a career as a professional in his own right was entrusted with developing the abilities of those whose talents were far in advance of his own (Frith, p. 32). According to John Callcott Horsley, his abilities as a painter were ‘nil’ (p. 32). Sass was nevertheless an astute educator (and businessman) and his college developed a reputation for excellence. Essentially a selective, fee-paying public school in the manner of others of the time – even if it only took a maximum of eighteen students, some of whom were boarders – its history involves the personalities of the proprietor, the daily life of the youths who attended, and the curriculum they followed. Like all public schools, it was characterized by rituals and traditions, and ultimately generated a series of mythologies.

An important ingredient was Sass’s character, and assessments of his personality vary. Many were positive. Though other instructors were employed, much of the work was done by Sass himself, and surviving accounts speak of him in affectionate terms as an able teacher. In The Newcomes (1855) Thackeray (who knew graduates of the school) includes an amusing account in which a Mr. Gandish is clearly modelled on Sass, and is used to comment on his real-life prototype. According to Thackeray, Gandish/Sass is ‘an excellent master’ and a ‘good critic’. He is, furthermore, a practised educationalist who knows how to balance praise and blame, encouragement and heading off mistakes before they become a problem. Mr. Gandish, Thackeray tells us, ‘was always’ giving out ‘sweetmeats of compliments and cordials of approbation’ (The Newcomes, 2, p. 168). Frith, who was a student at the school, takes a parallel view.

Frith calls him ‘Dear old Sass’ (p.32), a charismatic communicator who could be ‘severe’ (p.32), guiding his students through the principles of drawing while sometimes imposing his own, occasionally limited views on what constituted excellence. Frith particularly recalls a moment when Sass dismisses his interest in Dutch art as a ‘waste of time’ (p.32) while directing him to ‘the compositions of Michael Angelo and other great artists’ (p.33). Yet Sass did his best to immerse his students in the culture that would eventually become their own. The school was regularly visited by some of the leading artists of the time, and there were social events in which the students and their heroes mixed freely. The curriculum taught the rudiments of art, but the visitors modelled how a gentleman-artist should behave. Frith was awestruck, commenting how:

Mr Sass was accustomed to giving a series of conversazioni, at which great artists and other distinguished men were present. Etty, Martin (certainly one of the most beautiful human beings I ever beheld), and Constable were frequent visitors. We had dinners and dances, too. Who that had once seen Wilkie dance a quadrille could ever forget the solemnity of the performance … [p.33].

Others were less impressed, and regarded these displays as little more than self-promotion, the actions of a failed artist who tried to bolster his reputation through a process of association. Commentators generally agreed that Sass was a good teacher, but his flamboyant mannerisms irritated many. John Callcott Horsley describes him as ‘extraordinarily pompous’, a man ‘eaten up by vanity’ who had a Dickensian taste for ‘extravagant waistcoats of cut velvet’ (p.23), and Rossetti and Holman Hunt were equally critical.

However, the final words must be Frith’s. Frith regarded Sass as glamorous rather than vain, a man whose presence was enough to inspire his pupils in a way some teachers can: a unique quality. The artist completes his account by speaking compassionately of Sass’s later infirmity. While still in charge of the school, Sass began to behave in a disturbed and illogical way. Frith sadly notes how the Professor’s ‘temperate habits’ (p.35) gave way to curious behaviour and repetitiveness, symptoms the artist describes as a ‘sad affliction’ (p.37), and are instantly recognisable, at least to modern eyes, as the onset of Alzheimer’s disease. This led to his retirement; the school was bought and run by Cary, continuing the methods of its founder.

Life at the School

There are no official histories of the school, and no objective accounts of the students’ everyday life. There are anecdotes and satirical commentaries. Veering between the dramatic and the humorous, they probably give a truthful representation of everyday routines and rituals.

Some ex-students, such as William Frith, speak affectionately of the friendships they made and the school’s stimulating atmosphere. Others, such as Rossetti, found the curriculum unadventurous and the ambience stifling. Approved by academicians and modelled on a public school, Sass’s was both civilizing and barbarous, partaking of many of the more negative aspects of the elite education of the time. One of these, perhaps inevitably, was the intimidation of younger students by the older ones. Some of this was framed by masculine banter and ‘joshing’, and trainees sometimes applied their developing skills in art to the task of making fun of each other. A fictional account, no doubt reflecting real practice, is found in Thackeray’s The Newcomes (1855). According to Thackeray:

Caricatures of the students of course were passing constantly among them, and in revenge for one which a huge red-haired Scotch student, Mr. Sandy McCollop had made of John James, Clive perpetrated a picture of Sandy which set the whole room in a roar [so that] the Caledonian giant uttered satirical remarks against the assembled company, averring that they were a parcel of sneaks, a set of lick-spittles, and using epithets more vulgar …[I, 169].

This seems good-humoured enough in the caustic manner of teenagers, but the verbal (and visual) mockery quickly degenerates into fisticuffs: Clive won’t be insulted (in return) so he takes his fellow-student outside and swiftly administers ‘two black eyes … which prevented the young artist from seeing [the model] for some days’ (1, p.169). As in the great public schools of the time, violence was never far away, and like Charterhouse (where Thackeray’s nose was broken in a brawl), or Harrow (where Trollope endured miseries of loneliness and intimidation), Sass’s allowed bullying as a simple cultural fact. This state of affairs seems curiously at odds with the sensibilities of young men who were training to be poets of the brush, and sensitive students were sometimes unhappy and afraid. The most celebrated account involves John Everett Millais. Sent to Sass’s at the age of just nine, Millais’s brilliance made him into the classic ‘natural victim’ which climaxed in an extraordinary act of violence. Recounted in J.G. Millais’s memoir of his father’s life and letters, it paints a dim view of the standards of discipline and explicitly links the school to the ‘fagging’ and ‘thrashing’ mentality of Eton and the rest:

At Mr Sass’, as at most of the schools of the day, a good deal of bullying went on, and one of the students [made Millais’s] life a burden to him. The state of things reached a climax when, at the age of nine, young Millais gained the silver medal of the Society of Arts, for which this youth had also competed. The day following the presentation Millais turned up as usual … and after the morning’s work was over, H. (the bully) with the help of two other small boys whom he had compelled to remain, hung him head downwards out of the window, tying his legs up to the iron of the window-guards and scarves and strings. There he hung over the street in a position which shortly made him unconscious, and the end might have been fatal had not some passer-by, seeing the position of the child, rung the door-bell and secured his immediate release [12 –14].

This extreme event is emblematic of a serious problem, although J.G. Millais takes some pleasure in noting how the bully was expelled ‘and came to a miserable end’ (I, 14). Like any other school of its period, Sass’s nurtured youthful talent while accommodating the influence of a sometimes brutal machismo.

The Curriculum: Content and Dissent

There are no surviving documents that give precise details of time-tables or schemes of work, but the content of the curriculum is well-known. This was extremely traditional, and set out to teach the skills required to become a painter. Rigorous and exacting, it imposed the high standards expected by The Royal Academy.

Perspective and the uses of colour were part of the curriculum, but the training was focused on draughtsmanship, essentially drawing the human form. Students sometimes drew from the life, with male models as their subjects; but most of their time involved copying from prints and plaster casts of sculpture. The emphasis was purely on the classical: Antique statuary was presented as the aesthetic ideal and the students occasionally drew from the Elgin Marbles, which were close at hand in the British Museum (Gillett, pp. 74–75). Students rarely handled a brush; as Jan Marsh remarks, practically ‘all [of the] work was in pencil and, as stale bread was used as an eraser, the studio was ankle-deep in crumbs’ (p.11).

The course of general training usually lasted two years and was sometimes extended to three. Progress was monitored by regular inspection of a portfolio. Transition between years was allowed once the candidate had convinced Sass of the quality of his drawing, and entry to The Royal Academy was only realised when a ‘perfect portfolio’ had been produced, containing exemplary drawings of musculature, torsos and articulated forms.

This emphasis on drawing produced some excellent painters of the human form. Millais is a prime example, and so is Corbould. There were also dissenters. Some of the more experimental artists of the time reviled what they saw as an over-dependence on copying from the classical, and others questioned the logic of training artists to draw as if the language of art were no more than a mechanical skill. This resistance became more pronounced in the forties, when F. S. Cary had taken over and the school had been renamed after him: the Pre-Raphaelite revolution, with its anti-classical agenda, was about the change the direction of British art. Though Millais trained at Sass’s/Cary’s, Rossetti and Holman Hunt were contemptuous of the school’s course of study. In Hunt’s withering terms:

Many students who worked [at Cary’s] shaded their drawings with the most regular cross-hatching, putting a dot in every empty space; thus the figure was blocked out into flat angular surfaces … For all such systems I had neither time nor inclination … It [appeared to me] a waste of effort for an artist to rival the precision of an engine turning on a watch [I, 34-35].

Rossetti, predictably, was just as dismissive. A student at Cary’s, Rossetti studied from a human skeleton and some classical drawings; but he soon grew bored and after about a year (in 1844) his attendance declined. Jan Marsh ascribes his truancy to troubles at home (p.15), but in reality this type of hermetic copying from nature was never likely to appeal to Rossetti’s emphasis on atmosphere and passionate feeling. Interestingly, he never mastered the skills promoted by the school, and remained relatively untutored.

Note: After Sass's was renamed Cary's, it admitted women artists such as Anna Mary Howitt and Eliza Fox: in her letters, Howitt describes attending classes here. Cary even arranged sittings for her. — Many thanks to Dr. Gilles Weyns for this information

Bibliography

Engen, Rodney. Richard Doyle. Stroud: Catalpa Press, 1983.

[Frith, W.P.]. A Victorian Canvas, The Memoirs of W.P. Frith. Ed. Neville Wallis. London: Bles,. 1957.

Gillett, Paula. The Victorian Painter’s World. Gloucester: Sutton, 1990.

Holman Hunt, William. Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. 2 vols. London: Macmillan, 1905.

Horsley, John Callcott. Recollections of a Royal Academician. London: John Murray, 1905.

Lester, Valerie. Phiz: The Man who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto & Windus, 2004.

Marsh, Jan. Dante Gabriel Rossetti: Painter and Poet. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1999.

Millais, John Guille. The Life and Letters of John Everett Millais. 2 vols. London: Methuen, 1899.

Thackeray, W.M. The Newcomes: Memoirs of a Most Respectable Family. 2 vols. London: Bradbury & Evans, 1855.

Created 26 October 2012

Last modified 25 January 2026