illiam Warrington was one of the earliest stained glass makers of Victorian England. Possibly the son of a glazier (see Shepherd), he mentions once having reinstalled some glass "for Mr Willement, while in his establishment" (33n.), but was working on his own account by at least 1837, when he made his first window for A. W. N. Pugin at St Mary's College chapel, Oscott. He flourished at the beginning of the reign, continuing to make windows for Pugin (see Hill 229).

But he seems to have had a pugnacious nature, and his work later came in for undue criticism — largely brought on by his own attacks on others, and the high prices he began to charge. Pugin himself got annoyed with him: "He has become Lately so conceited that he has got nearly as expensive as Willement," he wrote to Lord Shrewsbury on 28 August 1841 (269). Pugin complained to his patron again on 29 September 1842, "were it not for such rascals as Warrington things would be deligtful [sic].... he is the most impudent & ungrateful villain I have ever dealt with" (380). Here was one of the reasons for Pugin's encouraging John Hardman to go into stained glass manufacture (see Hill 420). Meanwhile, Warrington also came under fire from the Ecclesiologists, who disliked his practice of making his glass look old by artificial means, calling it a "nauseous practice" (84), and panned his book, The History of Stained Glass (1848), for his misunderstanding of Greek, lack of originality and so on — and, perhaps most fundamentally, for using his own versions of older glass to illustrate it, which they saw as "illustrating mediaeval design by glorifying himself" (82). Jim Cheshire, who notes the animus against him, judges from a sample of churches in Devon that Warrington's business suffered as a result (46).

Stanley Shepherd concludes that Warrington's "early work with Pugin was perhaps his most notable and might be seen as potential unrealized, but he continued to make windows until 1866. He died on 4 June 1869 at Martello Cottages, Folkestone, Kent, aged seventy-three." His funeral, Shepherd adds, was held six days later at SS Mary and Eanswythe Church in Folkestone. Carole Moody, of the Friends of Cheriton Road Cemetery, Folkestone, has written in to say that he was buried in the municipal cemetery rather than in the churchyard, and that (sadly) his grave is unmarked.

Warrington's plot in Cheriton Road Cemetery, looking

west, photographed by Carole Moody.

However, this was not the end of the firm. Warrington had married and left at least one son, James Perry Warrington, who had been working with him since the early part of the decade, and kept the company going after his father’s death. By 1895 it was operating in Leeds, and lasted there "until at least c.1905" (see Allen). Although its style had changed little over the years when William Warrington was in charge, according to John Allen, his son moved away from his father's "garish colours and lack of understanding of the gothic" and adopted "a style more acceptable to contemporary taste" — Jacqueline Banerjee, with many thanks to Carole Moody for her information and photograph.

Works

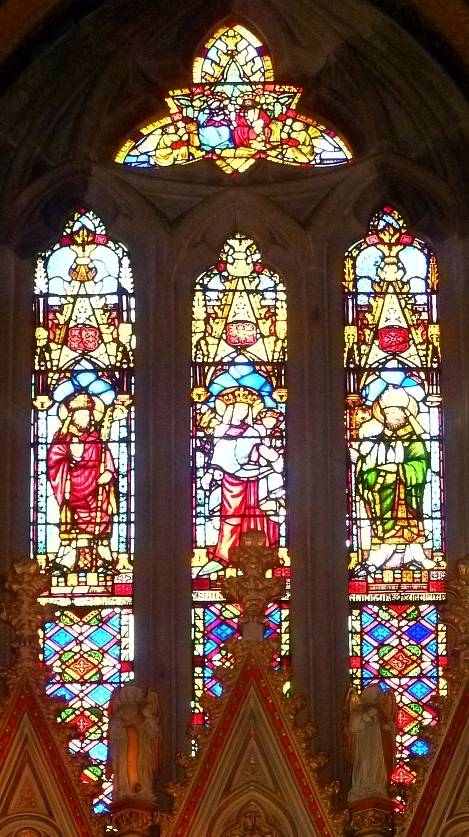

- St Chad, and the infant Jesus with St Chad, at St Chad's RC Cathedral, Birmingham (to Pugin's designs)

- East windows at St Chad's (to Pugin's designs)

- David and Goliath at St Oswald's, Ashbourne

Bibliography

Allen, John. "Architects and Artists WXYZ." Sussex Parish Churches. Web. 3 September 2021.

Cheshire, Jim. Stained Glass and the Victorian Gothic Revival. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2004.

The Ecclesiologist. Vol. X (New Series, Vol. VII). Google Books (free book). Web. 3 September 2021.

Hill, Rosemary. God's Architect: Pugin and the Building of Romantic Britain. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 2008.

Shepherd, Stanley A. "Warrington, William (1796–1869), stained-glass artist." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Onine ed. Web. 3 September 2021.

Warrington, William. The History of Stained Glass, from the earliest period of the art to the present time. London: William Warrington, 1848. Internet Archive. Contributed by the Getty Research Institute. Web. 3 September 2021.

Created 3 September 2021