Grace Aguilar’s “History of the Jews in England” was published anonymously in volume XVIII, no. 153 (1847) of Chambers’s Miscellany, pp. 1-32. No changes or corrections, grammatical or factual, have been made to the following transcribed text, which I have made from the Hathi Trust Digital Library’s online version of a copy in the University of California Library. — Lionel Gossman

he Hebrew nation, as is well known, has been for ages scattered over the face of the earth, and now exists in different portions in every civilised country; retaining, however, in all situations, the religion, manners, and recollections of its ancestry—almost everywhere less or more oppressed, yet everywhere possessing the same unconquerable buoyancy of spirit and the same indomitable industry. It would be a very long and dismal story to tell of the settlement and sufferings of the Jews in the various countries of Europe, and we propose, therefore, to confine ourselves to a brief narration principally concerning their residence and treatment in Great Britain.

Whence or by what route the exiles of Judea found their way to this island, cannot now be satisfactorily traced; but, scattered as they were over the extensive domains of their Roman conquerors, it is not unlikely that they originally crossed the Channel whilst England also was under imperial sway, their numbers increasing as centuries rolled on, and as the gradual desertion of the island by the Romans gave them a more peaceful and secure retreat than was enjoyed by their brethren scattered nearer the seat of empire.

During the struggles between the Britons and Saxons, and afterwards between Saxons and Saxons, till the Heptarchy was finally established, the Hebrew strangers remained unnoticed; but when Christianity was introduced, and monks and priests obtained supreme ecclesiastical authority, decrees were issued as early 740 by Egbert, archbishop of York, and again in 833 by the monks of Croyland, prohibiting Christians from appearing at Jewish feasts. From these decrees we infer that the Jews must have become both numerous and influential, and their feasts and ceremonies attractive to the people, who in the very early stages of Catholicism might have found a puzzling similarity in the outward ceremonies of the two religions—gorgeous mess and splendour being at that time characteristic of the rites of both. The distinctions of actual creed were too subtle and too carefully made the study of churchmen alone to be understood or cared for by the multitude, and the priests must have feared some danger to their new and simple-minded converts from a too close intimacy with the Hebrews, or these prohibitions need not have been made.

No further allusion being made to the Jews during the Saxon monarchy, the decrees of the priests were probably obeyed, and no excuse given for persecution. When Canute of Denmark conquered England, however, the Jews shared the servitude of their Saxon brethren; and in 1020, without any assigned cause but the will of the sovereign, were banished from the kingdom. They crossed the Channel, and took refuge in the dominions of William, Duke of Normandy, where they were so kindly received that, on his conquest of England and assumption of her crown, they returned, increased in numbers, to their old homes, and purchased from William the right of settlement in the island.

The sons of the Conqueror pursued their father's kindly policy towards them. Under William Rufus they established themselves in London and Oxford, erecting in the latter town three halls or colleges—Lombard Hall, Moses Hall, and Jacob Hall— where they instructed young men of either persuasion in the Hebrew language and the sciences. Until this reign the only burial-ground allowed them in all England was St. Giles, Cripplegate, where Jewen Street now stands; but under Rufus they obtained a place of interment also at Oxford, now the site of part of Magdalen College. Indeed Rufus, from what is narrated to us by the chroniclers, would appear to have respected the feelings of the Jews more than those of the Christian portion of his subjects. “He appointed,” says Milman, “a public debate in London between the two parties, and swore, by ‘the face of St Luke,’ that if the rabbins defeated the bishops, he would turn Jew himself. He received at Rouen the complaint of certain Jews, that their children had been seduced to the profession of Christianity. Their petition was supported by a liberal offer of money. One Stephen offered sixty marks for his son's restoration to Judaism, but the son had the courage to resist the imperious monarch. Rufus gave still deeper offence by farming to the Jews the vacant bishoprics.”

During this breathing-time from persecution their opulence naturally increased, and with it their unpopularity. The civil wars between Matilda and Stephen had drained the royal coffers; money became more and more imperatively needed; and, following the example of the continental nations, charges the most false, but from their very horror and improbability eagerly credited by the ignorant populace, were promulgated against the Jews, and immense sums extorted from them to purchase remission from suffering and exile. Those who refused acceptance of the royal terms were mercilessly banished, and their estates and other possessions confiscated to the crown.

During the reigns of Stephen and Henry II these persecutions continued with little intermission, yet still they remained industrious and uncomplaining, eager on every occasion to testify their loyalty and allegiance.

In the last year of Henry II's reign (1188), a parliament was convened at Northampton to raise supplies for an expedition to the Holy Land. The whole Christian population were assessed at £70,000, while the Jews alone, in numbers but a very small fraction of the king's native subjects, were burdened with a tax of £60,000; £3330 having been during this one reign already tortured from them. The abandonment of the project, followed as it was by the king's death, prevented this illegal extortion; and it was perhaps from joy at this unexpected relief that the Hebrews thronged in crowds to Westminster to witness the coronation of Richard, sumptuously attired, and bearing rich offerings, to testify their eager desire to conciliate the king.

This, however, was not permitted. The nobles and populace— whose strongest link of union in those days was jealous hatred of a people whose only crime was wealth—resolved on their exclusion. The presence of such ill-omened sorcerers at the coronation, it was declared, would blight every hope of prosperity for the reign, and commands were peremptorily issued that no Jews should be admitted to witness the ceremony. Some few individuals dared the danger of discovery, and made their way within the church. Their boldness was fatal; and not to themselves alone. Insulted and maltreated almost to death, they were dragged from the church, and the signal given for universal outrage. The populace spread through every Jewish quarter, destroying and pillaging without pause, setting even the royal commands at defiance; for avarice and hatred had obtained sole possession of their hearts. For a day and a night these awful scenes continued in London, and not a Jewish dwelling in the city escaped. England was at that time thronged with friars preaching the Crusade; and, as had previously been the case on the continent, they urged the sacrifice of the unbelieving Jews as a fit commencement for their holy expedition. The example of London was held forth as an exhibition of praiseworthy enthusiasm; and at Edmondsbury, Norwich, and Stamford the same scenes of blood and outrage were enacted. At Lincoln the miserable Hebrews obtained protection from the governor. At York, after a vain attempt to check the popular fury, a great number retreated to the castle with their most valuable effects. Those not fortunate or expeditious enough to reach the temporary shelter were all put to the sword, neither age nor sex spared, their riches appropriated, and their dwellings burnt to the ground.

For a short time the castle appeared to promise a secure retreat, but gradually the suspicion spread that the governor was secretly negotiating for their surrender, the price of his treachery being a large portion of their wealth. Whether this suspicion were correct or not was never ascertained, but it worked so strongly on the minds of the Jews, that they seized the first occasion of the governor's absence from the castle, on a visit to the town, to close the gates against him. They then themselves manned the ramparts, and awaited a siege. . It happened that the sheriff of the county (without whose permission no measures to recover the castle could be taken) was passing through York with an armed force; the incensed governor instantly applied to him, and demanded the aid of his men. Recollecting the king's attempt to keep peace between his Christian and Jewish subjects in London, the sheriff at first hesitated; but, urged on by the indignant representations of the governor, he at length permitted the assault.

The frantic fury with which the shouting rabble rushed to the attack, the horrid nature of the scenes which he knew must inevitably ensue, caused him, even at that moment, to revoke the order; but it was too late. License once given, the passions of the surging multitude could not be assuaged. The clergy fanned them into yet hotter flame, by encouraging their mad fury as holy zeal, promising salvation to all who shed the blood of a Jew; and themselves, in strange contradiction to the professions signified by the garbs they wore, joining in the affray, and often heading the attack. The unshrinking courage, the noble self-denial and heroic endurance of the hapless Hebrews, could little avail them against the wild excitement and immense multitude of their assailants; yet still they resisted with vigour. Accused as they were of never handling the weapons or experiencing the emotions of the warrior, it was now shown that circumstances and not character were at fault. The spirit of true heroism peculiar to their race in the olden time might indeed appear crushed and lost beneath the heavy fetters of oppression, but it burned still, ready to burst into life and energy whenever occasion demanded its display.

Notwithstanding the bold defence of the besieged, resistance was too soon seen to be hopeless, and in stern unbending resolution they assembled in the council-room. Their rabbi (a Hebrew word signifying chief or elder), a man of great learning and eminent virtue, rose up, and with mournful dignity thus ad dressed them:--“Men of Israel, the God of our ancestors is omniscient, and there is no one who can say, ‘What doest thou?’ This day he commands us to die for his law—that law which we have cherished from the first hour it was given, which we have preserved pure throughout our captivity in all nations, and for which, for the many consolations it has given us, and the belief in eternal life which it communicates, can we do less than die? Posterity shall behold its solemn truths sealed with our blood; and our death, while it confirms our sincerity, shall impart strength to the wanderers of Israel. Death is before our eyes; we have only to choose an easy and an honourable one. If we fall into the hands of our enemies, which fate you know we cannot elude, our death will be ignominious and cruel; for these Christians, who picture the Spirit of God in a dove, and confide in the meek Jesus, are athirst for our blood, and prowl like wolves around us. Let us escape their tortures, and surrender, as our ancestors have done before us, our lives with our own hands to our Creator. God seems to call for us; let us not be unworthy of that call.”

It was a fearful counsel, and the venerable elder himself wept as he ceased to speak; but by far the greater number declared that he had spoken well, and they would abide by his words. The few that hesitated were desired by their chief, if they approved not of his counsel, to depart in peace; and some obeyed. It was night ere the council closed, and during the hours of darkness not a sound betrayed the awful proceedings within the castle to the besiegers. At dawn the multitudes furiously renewed the attack, falling back appalled for the minute by the sight of flames bursting from all parts of the citadel. A few miserable objects rushing to and fro on the battlements also became visible, with wild cries intreating mercy for themselves, imploring baptism rather than death, and relating with groans and lamentations the fate of their companions. The men had all slain their wives and children, and then fallen by each others' hands, the most distinguished receiving the sad honour of death from the sword of their old chief, who was the last to die. Their precious effects were burnt or buried, according as they were combustible or not; so that, when the gates were flung open, and the rabble rushed in, eager to appropriate the wealth which they believed awaited them, they found nothing but heaps of ashes. Maddened with disappointment, all pledges of safety to the survivors, if the gates were opened, were forgotten, and every human being that remained was tortured and slain. Five hundred had already fallen by their own hands, and these voluntary martyrs were mostly men forced by persecution into such mean and servile occupations as to appear incapable of a lofty thought or heroic deed.

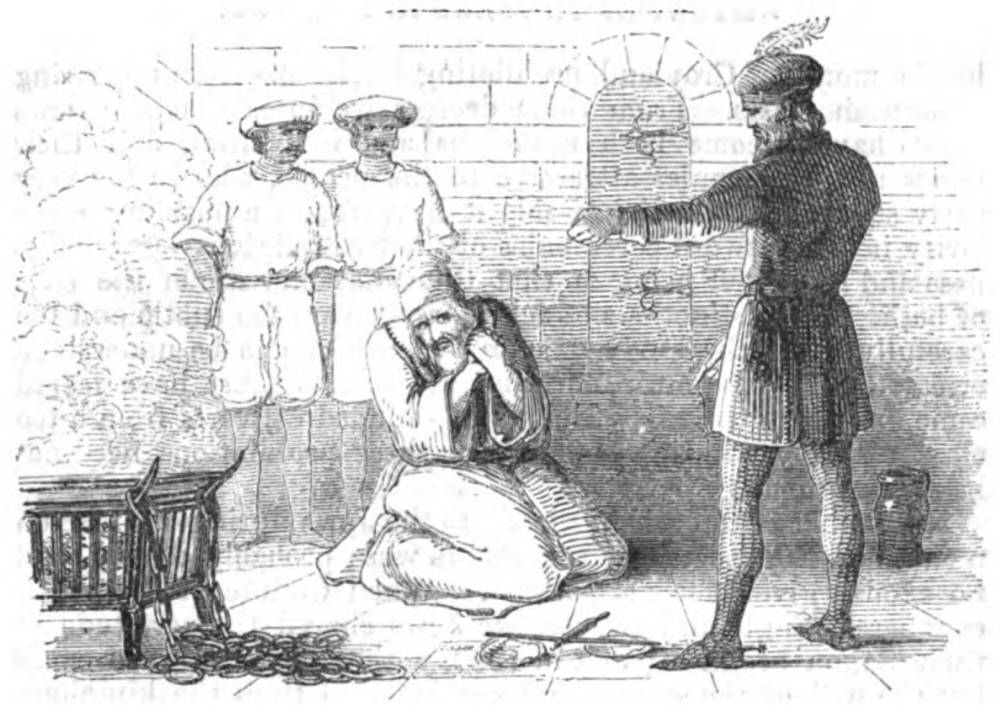

No punishment followed the atrocious proceedings at York. The laws of England never interfered in behalf of the king's Jewish subjects, though they would have been somewhat rigidly obeyed had the sufferers been the offenders. On King Richard's return from captivity, the Hebrews were, under certain statutes, acknowledged as the exclusive property of the crown. John commenced his reign with a semblance of extreme lenity towards them. The privileges formerly granted to them by Henry I. were confirmed. They might settle in any part of England, instead of being confined to certain quarters of certain towns; hold lands, and receive mortgages. Their evidence might be taken in courts of justice. All English subjects were commanded to protect their persons and possessions as they would the especial property of the king. Other laws equally lenient were issued; and, misled by such favourable appearances, many of the continental Hebrews flocked to England. This increase of Jewish population of course materially increased Jewish wealth; the hatred of the people was anew excited, and several indignities were perpetrated against the Jews. The king wrote a strong rebuke to the perpetrators; and then, at the very time that the Jews were rejoicing at this undeniable proof of his sincerity, and their own security, completely changed his policy, and from the extreme of lenity proceeded to the extreme of rigour. He had, in fact, only favoured them to multiply their wealth, and then revelled in its seizure; glad that there were now some possessions he could appropriate without any interference from the pope. The unhappy Israelites were imprisoned, tortured, murdered, and their treasures all confiscated to the crown. A Jew of Bristol having refused to betray his hoards, was condemned to have a tooth pulled out every day until he should yield. The man suffered seven of his teeth to be extracted before he complied: the king gained 10,000 marks by his cruel device. In the war between John and his barons they were persecuted by both parties—by the king for their wealth; by the barons, because they were vassals of the king. Even the stern and noble assertors of liberty, the heroes of the Magna Charta, seeking justice and freedom for all classes of Englishmen, had no pity for the wretched Jews; seizing their possessions, and demolishing their homes, to repair the walls of London, which had been greatly injured in the civil war.

The guardians of England during the reign of Henry III sought in some degree to meliorate the condition of the Jews. Twenty-four burgesses of every town, where they resided, were appointed to protect their persons and property; but the protection even of royalty could avail little when every class of men conspired to detest and oppress them. The merchants were jealous of the privileges permitting the Jews to buy and sell. The people hated them, from the idle tales of horrible crimes attributed to them, which had no foundation whatever in truth, but which ignorance and prejudice not only believed, but so magnified and multiplied as to cause them to be inseparably associated with the word Jew. The clergy—men who, both professors and preachers of a religion of peace, should have been the first to protect §.the injured, and calm the turbulent passions of the populace--werethe constant incitors to persecution and cruelty, believing, by a most extraordinary hallucination, that to maltreat the Jew was the surest evidence of Christian zeal.

The guardians of the young king had, however, so guided him, that for a brief interval after attaining his majority, the royal protection shielded the Jews in some measure from popular oppression. But this was only until the king's coffers became impoverished: when these were empty, the only means of re filling them was to follow the example of his predecessors, and by fair means or foul, extort money from the Jews. In this reign alone, the enormous sum of 170,000 marks was, under various pretences and various cruelties, wrung from them; and when all other means of extortion seemed exhausted, an extraordinary spectacle was displayed in the convention of a Jewish parliament. The sheriffs of the different towns had orders to return six of the wealthiest and most influential Jews from the larger cities, and two from the smaller. In those times almost the only function of a parliament was to vote supplies; this Jewish parliament, therefore, in being informed by the sovereign that he must have 20,000 marks from the Jews of England, served for the Jewish part of the population pretty nearly the same purpose as the ordinary parliament served for the rest of the community. The assembled members were probably left to decide the amount of assessment which the various ranks of Jews should pay, so as to make up the total sum required; and as this right of proportioning the assessment was generally the only right exercised by ancient parliaments, properly so called, the particular hardship of the Jews, as compared with their fellow subjects, consisted not in having no liberty of refusal—for that is a liberty which only modern parliaments have acquired—but in the enormous sum demanded from them, and in the rigours which they knew would be employed to enforce its speedy collection. Assembled, and made aware of the demand which was made upon them, the unfortunate Jewish representatives were dismissed to collect the money from their own resources as speedily as possible; and because it was not forthcoming as quickly as was requisite for the royal necessities, all their possessions were seized, and their families imprisoned.

Believing, at length, that their wealth must be exhausted by such demands, or weary of the trouble of extortion, Henry consummated his acts of oppression by actually selling his Jewish subjects, their persons and effects, to his brother Richard, Earl of Cornwall, for 5000 marks. The records of this disgraceful bargain are still preserved; and that the king had power to conclude it, marks the oppressed and fearful position of this hapless people more emphatically than any lengthened narrative. Yet the bar barity of the sovereign met with universal approbation; the wretchedness of the victims with neither sympathy nor commiseration.

On the election of Richard of Cornwall as king of the Romans, the Jews became again the property of the crown, and were again sold by Henry. This time their purchaser was the heir to the throne, Prince Edward, by whom they were sold, to still better advantage, to the merchants of Dauphine; and this traffic was actually the sale and purchase of human beings, in all respects like ourselves, gifted with immortal souls, intelligent minds, and the tenderest affections. Husbands, fathers, sons, wives, mothers, innocent childhood, and helpless age. The sufferers were inoffensive and unobtrusive, seeking no vengeance, patient, and even cringing under all their injuries. Of all the crimes imputed to them, and some of these were of the most horrible nature, not one appears ever to have been really proved against them, except, perhaps, that of clipping the coin of the realm; and even on this point the evidence is not clear. And yet, had all the accusations against them been true, one could hardly have wondered, considering their treatment. (i.e. one could hardly have been surprised given the treatment to which they were subjected)

After the battle of Lewes, reports became current that the Hebrews at Northampton, Lincoln, and London had sided with the king against the barons. This of course roused the latter in their turn to plunder and destroy; while Henry annulled his bargain with his son, and for a while treated them with greater lenity. But again one of the usual excuses for persecution—insult offered by the Jews to some symbol reverenced by the Catholics—found voice, and not only were extortions renewed, but a solemn statute was passed, disqualifying the Jews from possessing any lands or even dwellings. They might not erect any new habitations, only repair their present homes, or rebuild on the same foundations.

All lands and manors already in their hands were violently wrested from them; and those held in mortgages returned to their owners without any interest on the bonds. All arrears of charges were demanded, and imprisonment threatened if payment were postponed. An extortion apparently more oppressive than all the rest, as we find the distress it occasioned amongst the Jews actually moved the pity of their rivals, the Caorsini bankers, and of the friars, their deadliest foes.

The death of Henry was so far a reprieve that the above-named extortion was suspended; but the accession of Edward I only aggravated their social bondage. Laws as severe, if not more severe in some respects than those of previous sovereigns, were issued against them, followed by an act of parliament prohibiting all usury, and desiring the Jews to confine themselves to the pursuits of traffic, manufactures, and agriculture; for which last, though they could not hold, they might hire farms for fifteen years. But how could men, debarred so long from similar occupations, so debased by oppression, with minds so disabled, as to render it difficult for them to commence any new pursuit, obey so violent a decree? Had they received the fit education for traffic, manufactures, and agriculture before the laws commanding such employments were passed, there would have been many glad and eager to obey them; but, as it was, obedience was impossible. That usurers and Jews in the dark ages were synonymous, and that the Jews in their capacity of money-lenders did exhibit an extraordinary spirit of rapacity and extortion, cannot be denied. But although this spirit of money-making, even by methods esteemed dishonourable, characterising, as it did, the Jews of the Roman empire, as well as those of Europe in the middle ages, must be referred partly to an inherent national bent; there can be no doubt that much of the meanness and criminality displayed by the Jews of the middle ages, in their quest of wealth, is attributable to the binding oppression which absolutely fettered them to that one pursuit. Even if there were times when a Shylock pressed for his pound of flesh, when it would have been nobler to show mercy, was it unnatural? Can we ever expect oppression to create kindness—social cruelty to bring forth social love?

After eighteen years of persecution, little varied in its nature and its causes from the persecutions of previous reigns, the seal was set on Jewish misery by an edict of total expulsion, issued in 1290. All their property was seized except a very scanty supply, supposed sufficient to transport them to other lands. No reason was given for this barbarous proceeding. The charge previously brought against them of clipping and adulterating the coin of the realm, for which 280 had been executed in London alone, was never fully proved; nor, as might naturally have been expected, had the charge been really true, was the cause of their expulsion. A people's unfounded hate, and a monarch's cruel pleasure, exposed 16,511 human beings to all the miseries of exile. There were very few countries which were not equally inhospitable; for edicts of expulsion had gone forth from many of the continental kingdoms. Even if they could find other homes, the confiscation of all their property before they left England exposed them to multiplied sufferings, which no individual efforts could assuage; and the loss of life ever attendant on these wholesale expulsions is fearful. The greater number probably never lived to reach another shore; and to what retreats those who were more fortunate betook themselves, history does not say. From this date (1290), therefore, all trace of the English Jews, properly so called, is lost.

Their great synagogue, situated in Old Jewry, was seized by an order of friars, called Fratres de Sacra or De Pententia, who had not been long established in England. In 1805, Robert Fitzwalter, the greater banner-bearer of the city, and whose house it adjoined, requested, we are told by the old chroniclers, that it might be assigned to him; a request no doubt complied with in return for a good round sum of money. During the fifteenth century it belonged to two or three successive mayors, and was ultimately degraded into a tavern, known by the sign of the Windmill. The locality of this early Jewish house of worship, however, still retains its name and associations as Old Jewry.

Their valuable libraries at Stamford and Oxford were appropriated by the neighbouring monasteries. From that at Oxford, fifty years previous to their expulsion, Roger Bacon is said to have derived much of that chemical and astronomical information which enabled him to startle the age in which he lived by the boldness and novelty of his views. The Babylonian Talmud, a series of gigantic tomes, of which, and of lesser works com piled from them, the Jewish libraries were composed, contained elaborate treatises on the various sciences which occupied the attention of the learned in the middle ages; including of course magic and astrology; and as it was to the Franciscan convent at Oxford, by which the Hebrew library had been appropriated that Roger retreated on his library return had to England from Paris, it is by no means improbable that he may have been indebted to the Hebrew books thus placed within his reach.

From the year 1290 to 1655 the shores of Great Britain were closed against the Jews. No attempt ever appears to have been made on their part to revoke the order of expulsion. Oppression, perhaps, had left too blackened traces on their memories for England to be regarded with that strong feeling of local attachment which bound them, even after expulsion, so closely to Portugal and Spain. In France they were once and again recalled after being expelled. In the German and Italian states they were constantly persecuted and murdered by thousands, but never cast forth from the soil. In Spain and Portugal they had always held the highest offices, not only in the schools, but in the state and the camp; nay, royalty itself, in more than one instance, was closely connected with Jewish blood. Oppressive exactments and degrading distinctions were frequently made, but never interfered with the positions of trust and dignity which the larger portion of the nation enjoyed; so that when the edict of their universal expulsion from the peninsula came in 1492, there was no galling remembrance of debasing misery to conquer the love of fatherland, so fondly fostered in every human heart. Notwithstanding the danger from the constant dread of death, if discovered, secret Jews peopled the most Catholic kingdoms of Portugal and Spain. The extraordinary skill and ingenuity with which these Spanish and Portuguese Jews preserved their secret, and their numerous expedients for the strictest adherence to their ancient religion, under the semblance of most orthodox Catholicism, constitute a romance in history. If ever exposed to the suspicion of the Inquisition, however, the love of land was sacrificed to personal security; the suspected individuals taking refuge either in Holland, or in some of the newly-discovered East and West India Islands, and there making public profession of their ancient faith.

Joseph Ben Israel was one of these fugitives. He was a Portuguese Jew, and a resident of Lisbon. Suspicion of secretly following Judaism having fallen upon him, he was twice incarcerated by the Inquisition, and twice released, from the impossibility of proving the charge against him. When confined within those dangerous precincts a third time, he would not wait another examination, but succeeded in scaling the walls of his prison, and secretly flying from Portugal, bearing with him his young son Menasseh. At Amsterdam, where Ben Israel settled, both father and son received the peculiar covenant of their faith, and publicly avowed and confessed it. In the Jewish college of that city Menasseh Ben Israel received his education; and so remarkable was his progress in the difficult studies of the Hebrew Accolyte, that when only seventeen he succeeded his master, Isaac Uzieli, as preacher in the synagogue and expounder of the Talmud, and commenced the then difficult task of arranging and amplifying the scanty rules of the Hebrew language in the form of a grammar—a work obtaining him much fame, not only from the extreme youth of the writer, but also for the assistance it rendered to the learned men of all countries in the attaining of a language so little known, yet so much valued. The grammar was speedily followed by numerous other works, written both in Spanish and Latin. Their subject is mostly theology; but Ben Israel’s own learning was not confined to sacred subjects alone. Well versed in Hebrew, Greek, Arabic, Latin, Spanish, and Portuguese, he not only wrote these languages with ease and fluency, but was well acquainted with the literature of each, and had thus, by extensive culture and thought on a great variety of subjects, acquired larger views and sentiments than were possessed by the generality of his race.

The confiscation of all his paternal property at Lisbon compelled him to resort to commerce—an interruption to his literary pursuits. which he would have gladly eluded; but, already a husband and a father, he met the necessity cheerfully, and soon became as influential and as highly respected in commercial affairs as in literature; in which, notwithstanding the many and pressing calls of business, he never allowed his labours to relax. After the marriage of his daughter, he visited, partly for pleasure and partly on business, the Brazils, where his brother-in-law and partner resided. It was a very unusual thing in those days for any Hebrew to travel: the minute and numerous ordinances of the Talmud interfering too closely with daily life, and rendering it difficult to obey them anywhere save in cities, where there were communities of Jews.

But Menasseh Ben Israel, while he gloried in being inwardly and outwardly a follower of the Hebrew faith, had a mind capable of distinguishing between the form and the spirit. The death of his eldest son, a youth of great promise, occurred soon after his return from Brazil, and caused him such intense grief, as, according to his own acknowledgment, to render him incapable of the least mental exertion. His only comfort and resource was the perusal of that Holy Book which had been the origin and end of all his studies. It did not fail him in his grief; and after some severe struggles, energy returned.

His literary fame had procured him the intimacy and friend ship of the most eminent and learned men throughout Europe. Amongst these was John Thurloe, who, in the year 1651, had gone to the Hague as secretary to St John and Strickland, ambassadors from England to the states of the United Provinces. During his stay in Holland he became acquainted with Ben Israel, and with his earnest but then apparently fruitless wishes for the readmission of his nation into England. In 1653, Thurloe became secretary of state to Cromwell; and, discovering the enlarged and liberal ideas which the Protector individually entertained, he ventured, on his own responsibility, to invite Menasseh Ben Israel to the court of England and introduced him to Cromwell in 1655. The independence, the amiable qualities, and the great learning of the Jewish stranger, obtained Cromwell's undisguised friendship and regard. Three hundred and sixty five years had elapsed since a Jew had stood on British ground; and during that interval many changes and improvements, national and social, had taken place. The reformation had freed England from the galling fetters of ignorance and superstition which must ever attend the general suppression of the word of truth. Increase of toleration towards the Jews was already visible in those parts of the continent which were under Protestant jurisdiction; and it was therefore extremely natural in Menasseh Ben Israel to regard England as one of those favourite countries of Providence, where his brethren might enjoy security and rest.

Whether or not a formal act of readmission was passed during the Protectorship, is to this day a question. On the 4th of December 1655, a council was held at Whitehall, composed of the Lord Chief-Justice Glynn, Lord-Chief Baron Steele, the lord mayor and sheriffs of London, and sundry merchants and divines, to consider the proposals of Menasseh Ben Israel, which may be condensed into the following:—1. That the Hebrew nation should be received and admitted into the commonwealth under the express protection of his highness, who was intreated to command all generals and heads of armies, under oath, to defend them as his other English subjects on all occasions. 2. That public synagogues, and the proper observance of their religion, should be allowed the Jews, not only in England, but in all countries under English jurisdiction. 3. That a cemetery or grave-yard out of the town should be allowed them, without hindrance from any. 4. That they should be permitted to merchandise as others. 5. That a person of quality should be appointed to receive the passports of all foreign Jews who might land in England, and oblige them by oath to maintain fealty to the commonwealth. 6. That licence should be granted to the heads of the synagogue, with the assistance of officers from their own nation, to judge and determine all differences according to the Mosaic law, with liberty to appeal thence to the civil judges of the land. 7. That in case there should be any laws against the nation still existing, they should, in the first place, and before all things, be revoked, that by such means the Jews might remain in greater security under the safeguard and protection of his serene highness.

The council met again on the 7th, 12th, and 14th of December, on the last of which days, according to some authorities, the Jews were formally admitted; but, according to others, the council reassembled on the 18th, and dissolved without either adjournment or decision, the judges only declaring that there was no law prohibiting the return of the Jews. Burton, in his History of Oliver Cromwell, relates that the divines were divided in opinion; but on some asserting that the Scriptures promised their conversion, the Protector replied, “that if there were such promise, means must be taken to accomplish it, which is the preaching of the gospel; and that cannot be had, unless they were admitted where the gospel was publicly preached.”

Thomas Violet, a goldsmith, drew up a petition in 1660 to Charles II and his parliament, intreating that the Jews might be expelled from England, and their property confiscated; and in this petition he asserts that, in consequence of the decided disapproval of the clergy in the celebrated council of 1655, the proposal for their readmission had been totally laid aside. Bishop Burnett, in his “History of his own Times,” refutes this assertion, and declares that, after attentively hearing the debates, Cromwell and his council freely granted Ben Israel's requests; and this appears really to have been the case, for the very next year, 1656, a synagogue for the Spanish and Portuguese Jews was erected in King's Street, Duke's Place, and a burial-ground at Mile End, now the site of the hospital for the same congregation, taken on a lease for nine hundred and ninety-nine years.

Leaving the question, then, as to whether or not an act of readmission really passed, it is evident that the deed of toleration, granted from the Protector individually, did a as much for the real interests of the Jews as any formal parliamentary enactment. From that time the Jewish nation have found a secure and peaceful home, not in England alone, but in all the British possessions. We shall perceive, as we proceed, that prejudice was still often and violently at work against them; but though it embittered their social position, it did not interfere with their personal security, or prevent the º; observance of their faith.

The pen of Menasseh Ben Israel had not been idle during this period of solicitation and suspense. Under the title of “Vindicie Judaeorum” (“Defence of the Jews”), he published a work in which he ably and fully refuted the infamous charges which in darker ages had been levelled against his brethren. He had received, too, his degree as physician; and thus united the industry and information requisite for three professions—literature, commerce, and medicine. “He was a man,” we are told, “without passion, without levity, and without opulence.” Persevering and independent, full of kindly affection, and susceptible of strong emotion, with all the loftiness of the Spanish character, tempered, however, with qualities which gained for him the regard of the best and most learned men of his age. He did not continue in England—though it has been said he was solicited to do so by Cromwell—but rejoined his brother at Middleburg in Zealand, where he died in the year 1657.

The reign of Charles II beheld the Jews frequently attacked and seriously annoyed by popular prejudice; but their actual position as British subjects remained undisturbed. Thomas Violet’s petition we have already noticed; but its vindictive spirit did harm only to its originator. Four years afterwards, the security of their persons and property being threatened, they appealed to the king, who declared in council, that as long as they demeaned themselves peaceably, and with submission to the laws, they should continue to receive the same favours as formerly. At Surinam, the following year, the British government, by proclamation, confirmed all their privileges, guaranteed the full enjoyment and free exercise of their religion, rites, and ceremonies; adding, that any summons issued against them on their Sabbaths and holidays should be null and void; and that, except on urgent occasions, they should not be called upon for any public duties on those days. That civil cases should be decided by their elders, and that they might bequeath their property according to their own law of inheritance. All foreign Jews settling there were recognised as British-born subjects, and included in the above-enumerated privileges. As a proof how strongly the affections of the Hebrews were engaged towards England by this exhibition of tolerance, we may mention that when Surinam was conquered by, and finally ceded to the Dutch, although their privileges were all confirmed by the conquerors, they gave up their homes, synagogues, and lands, and braved all the discomforts of removal, and settled in Jamaica and other English colonies, rather than live under a government hostile to Great Britain.* [* Surinam, or Dutch Guiana, situated on the north-eastern coast of South America, is still almost peopled with Jews; but they are emigrants from the Dutch possessions in Europe, not descendants of the former Anglo-Jewish settlers.]

In 1673 we find prejudice again busy, in an indictment, charging the Jews with unlawfully meeting for public worship. They again unhesitatingly appealed to the king, petitioning that, during their stay in England, they might be unmolested, or that time might be allowed them to withdraw from the country. Charles, pursuing his previous policy, peremptorily commanded that all proceedings against them should cease; and during the remainder of his reign no further molestation occurred.

On the accession of James II. old prejudices were renewed, and thirty-seven Jewish merchants were arrested on the Exchange for no crime or fault, but simply from their non-attendance on any church. Certain writs in statute 23 of Elizabeth, instituted, probably, to suppress innovations in Protestantism, were the pretext for this aggression. James, as his brother had done, befriended the Jews; and summoning a council composed of the highest dignitaries of his realm, both church and laymen, declared “that they should not be troubled on this account, but they should quietly enjoy the free exercise of their religion as long as they behaved themselves dutifully and obediently to the government.”

The foregoing was the last public annoyance to which they were subjected in England. In 1690, indeed, a petition was sent to King William III from the council of Jamaica, that all Jews should be made to quit the island; but it was positively refused. And we infer that King William's sentiments towards the Israelites must have been even more favourable than those of his predecessors, from the circumstance that a great increase of Jews took place in England during his reign. Until this reign, one synagogue had sufficed; the service and laws of which were conducted according tothe principles of the Spanish Jews. In1692 the first German synagogue was erected in Broad Court, Duke's Place; and from that time two distinct bodies of Jews, known as Spanish and Portuguese, German and Dutch, have been naturalised in England. No new privileges were granted them, however, during the reigns of either William or Anne.

It is not till the ninth year of George I, 1723, that we can discover a parliamentary acknowledgment of their being British subjects; granting them a privilege, which, in the present age, it would appear meagre enough, but which, at the time of its bestowal, marked a very decided advance in popular enlightenment. “Whenever any of his majesty's subjects, professing the Jewish religion, shall present themselves to take the oath of adjuration, the words on the faith of a Christian shall be omitted out of the said oath; and the taking of it by such persons professing the Jewish religion without the words aforesaid, in the manner as Jews are admitted to be sworn to give evidence in the courts of justice, shall be deemed a sufficient taking.”

In the reign of George II, 1740, another act of parliament passed, recognising all Jews who resided in the American colonies, or had served as mariners during the war two years in British ships, as “natural born subjects, without taking the sacrament.” Thirteen years afterwards, the naturalisation bill passed, but was repealed the year following, according to the petitions of the city of London, and other English towns. Since then the Jews have gradually gained ground in social consideration; but all attempts to place them on an exact equality with other British subjects of all religious denominations, by removing the disabilities which the more fondly they cling to the land of their adoption, the more heavily oppress them, have as yet been unavailing.

By the multitudes, the Jews are still considered aliens and foreigners; supposed to be separated by an antiquated creed and peculiar customs from sympathy and fellowship—little known and still less understood. Yet they are, in fact, Jews only in their religion—Englishmen in everything else. In point of fact, therefore, the disabilities under which the Jews of Great Britain labour are the last relic of religious intolerance. That which they chiefly complain of is, being subjected to take an oath contrary to their religious feelings when appointed to certain offices. In being called to the bar, this oath, as a matter of courtesy, is not pressed, and a periodical act of indemnity shelters the delinquent. Jews, therefore, now practise at the bar, but only by sufferance. The same indulgence has not been extended to entering parliament, and consequently no Jew is practically eligible as a member of the House of Commons. Is it not discreditable to he common sense of the age that such anomalies should exist in reference to this well-disposed and, in every respect, naturalised portion of the community?

Social Arrangements of the English Jews.

n externals, and in all secular thoughts and actions, the English naturalised Jew is, as already mentioned, an Englishman, and his family is reared with the education and accomplishments of other members of the community. Only in some private and personal characteristics, and in religious belief, does the Jew differ from his neighbours. Many of the British Jews are descended from families who resided some time in Spain; others trace their origin to families from Germany. There have always been some well-defined differences in the appearance, the language, and the manners of these two classes. The Spanish Hebrews had occupied so high a position in Spain and Portugal, that even in their compulsory exile their peculiarly high and honourable principles, their hatred of all meanness, either in thought or act, their wealth, their exclusiveness, and strong attachment to each other, caused their community to resemble a little knot of Spanish princes, rather than the cowed and bending bargain-seeking individuals usually known as Jews.

The constant and enslaving persecution of the German Hebrews had naturally enough produced on their characters a very different effect. Nothing degrades the moral character more effectually than debasing treatment. To regard an individual as incapable of honour, charity, and truth, as always seeking to gratify personal interest, is more than likely to make him such. Confined to degrading employment, with minds narrowed, as the natural consequence—allowed no other pursuit than that of usury, with its minor branches, pawnbroking and old clothes selling—it was not very strange, that when the German Hebrews did make their way into England, and were compelled, for actual subsistence, still to follow these occupations, that their brethren from Spain should keep aloof, and shrink from all connexion with them. Time, however, looks on many curious changes: not only are the mutual prejudices of the Jews subsiding, but the position of the two parties is transposed. The Germans, making good use of peace and freedom, have advanced, not in wealth alone (for that even when oppressed, they contrived to possess), but in enlightenment, influence, and respectability. Time, and closer connexions with the Spanish Hebrews, will no doubt produce still further improvements.

These distinguishing characteristics, which we have just pointed out, belong, with some modifications, to the poor as well as the rich of these two Jewish sects. The faults of the poor Spanish and Portuguese Jews are so exactly similar to those of the lower orders of the native Spaniards, that they can easily be traced to their long naturalisation in that country. Pride is their pre dominant and most unhappy failing; for it not only prevents their advancing themselves, either socially or mentally, but renders powerless every effort made for their improvement. The Germans, more willing to work, and push forward their own fortunes, and less scrupulous as to the means they employ, are more successful as citizens, and as a class are less difficult to guide. Both parties would be improved by the interchange of qualities. And comparing the present with the past, there is some reason to believe that this union will be effected on British ground, and that the idle distinctions of Spanish and Portuguese, Dutch and German, will be lost and consolidated in the proud designation of British Jews.

The domestic manners of both the German and the Spanish Jews in Great Britain, are so exactly similar to those of their British brethren, that were it not for the observance of the seventh day instead of the first, the prohibition of certain meats, and the celebration of certain solemn festivals and rites, it would be difficult to distinguish a Jewish from a native household. The characteristics so often assigned to them in tales professing to introduce a Jew or a Jewish family, are almost all incorrect, being drawn either from the impressions of the past, or from some special case, or perhaps from attention to some Pole, Spaniard, or Turk, who may just as well be a Polish or Spanish Christian, or Turkish Mussulman, as a Jew. These great errors in delineation arise from the supposition, that because they are Hebrews they must be different from any other race. They are distinct in feature and religion, but in nothing else. Like the rest of the human race, they are, as individuals, neither wholly good nor wholly bad; as a people, their virtues very greatly predominate. Even in the lowest and most degraded classes, we never find those awful crimes with which the public records teem. A Jewish murderer, adulterer, burglar, or even petty thief, is actually unknown. This may perhaps arise from the fact, that the numerous and well-ordered charities of the Jews prevent those horrible cases of destitution, and the consequent temptations to sin, from which such a mass of crime proceeds. A Jewish beggar by profession is a character unheard of; nor do we ever find the blind or deformed belonging to this people lingering about the streets. The virtues of the Jews are essentially of the domestic and social kind. The English are noted for the comfort and happiness of their firesides, and in this loveliest school of virtue, the Hebrews not only equal, but in some instances surpass, their neighbours. From the highest classes to the most indigent, affection, reverence, and tenderness mark their domestic intercourse. Three, sometimes four generations, may be found dwelling together—the woman performing the blended duties of parent, wife, and child; the man those of husband, father, and son. As members of a community, they are industrious, orderly, temperate, and contented; as citizens, they are faithful, earnest, and active; as the native denizens of Great Britain, ever ready to devote their wealth and personal service in the cause of their adopted land.

Both the Spanish and German congregations have their respective charities, either founded by benevolent individuals, or supported by voluntary contributions and annual subscriptions. There are schools for poor children of both sexes and all ages, from the infant too young to walk, to the youth or maiden ready for apprenticeship; orphan asylums and orphan societies for clothing, educating, maintaining, and apprenticing both male and female orphans; hospitals for the sick, comprising also establishments for lying-in women, and an asylum for the aged; societies, far too numerous to specify by name, for clothing the poor; for relieving by donations of meat, bread, and coals; for cheering the needy at festivals; for visiting and relieving poor women, when confined, at their own dwellings, and enabling them to adhere to the rites of their religion in naming their infants; for allowing the indigent blind a certain sum weekly, which they forfeit if ever seen begging about the streets; for granting loans to the industrious poor, or gifts if needed; for outfitting boys who are to quit the country, and granting rewards for good behaviour to servants and apprentices; for furnishing persons to sit up with the sick poor, and granting a certain sum for the maintenance ofpoor families during the seven days' mourning for the dead, a period by the Jews always kept sacred; for relieving distressed aliens of the Jewish persuasion; and, amongst the Portuguese, for granting marriage-portions, twice in the year, to one or more fatherless girls, and for giving pensions to widows. There are also almshouses for twenty-four poor women annexed to the Spanish and Portuguese synagogue, and others in Globe Lane for ten respectable poor families of the same congregation; and not many years ago, a philanthropic individual (A. L. Moses, Esq. of Aldgate) erected almshouses for twelve poor families of the German congregation, with a synagogue attached, in Bethnal Green Road, at his own sole expense.

When we remember how small is the number of Jewish denizens in the great city of London, compared with its Christian population, and observe the variety and number of these charities, we are surely borne out in our assertion, that benevolence is a very marked characteristic of the Jews. Nor is it a virtue confined to the rich. Beautiful is that charity which is shown by the poor to the poor, and it is in this that the Jews excel. To relieve the needy, and open the hand wide to their poor brother, is a repeatedly-enforced command of their religion, which they literally and lovingly obey. On the eve of their great festival, the Passover, the door of the poorest dwelling may be found open, an extra plate, knife, and fork laid on the frugal table; and, whoever needs food, or even lodging, for that holy festival, may freely enter and appropriate to himself the reserved seat. That he may be quite a stranger is of little consequence; he is a Hebrew, and needy, and is therefore welcome to the same fare as the family themselves partake.

Nor are these charities confined only to their own race; they never refuse assistance, according to their means, whatever may be the creed. Neither prejudiced nor penurious in calls of philanthropy, their heart is open as their hand; and if they amass gold too eagerly, the fault is in some degree atoned by the use to which it is applied. Nor can it be doubted that as time rolls on, and even the remembrance of persecution is lost in the peace and freedom which will be secured them, the mind as well as the heart will be enlarged; and that while they shall still retain their energy and skill on the Exchange and in the mart, literature and art will enliven and dignify their hours at home. We may mention as a hopeful symptom the recent establishment of the “Jews' and General Literary and Scientific Institution” (the Sussex Hall of Leadenhall Street). Here Spanish and German Jews meet on common ground; classes, lectures, and an excellent library are open alike to the artisan, the tradesman, the merchant, the professor, and the idler; and from the eagerness with which all classes avail themselves of the advantages afforded by the institution, it would appear that its value is duly appreciated.

The domestic government of the Hebrews is very simple. Each synagogue is, as it were, a little independent state, governed by a sort of parliament, consisting of parnassim or wardens, gaboy or treasurer, and elders, with an attendant secretary, the congregation of the synagogue being like the members of a state. The wardens have the general superintendence of all the affairs of the congregation: the treasurer, the charge of all the sums coming into his hands for the use of the congregation, and of their expenditure. These officers are elected yearly—two wardens being chosen about Easter, which is generally the time of the Jewish Passover; and two more, and the treasurer, about Michaelmas, at the conclusion of the Jewish feast of Tabernacles. Four wardens, or parnassim, therefore, act together; each per forming the part of president three months alternately, and during the time of his presidency, considered as the civil head of the little community, and receiving certain honours accordingly.

The wardens and treasurer, attended by the secretary, whose business it is to take note of their proceedings, and bring cases before them for their consideration, meet once or twice a-week in a large chamber adjoining the synagogue, to make grants of monies, distribute relief, and endeavour, by strict examination and impartial judgment, to settle all causes and disputes according to the laws, institutions, and penalties of the Jewish state (that is, synagogue), and so prevent the scandal ofbringing petty offences and domestic differences before the English law. If, however, they cannot succeed in making peace, or the offence is of so grave a nature as to interfere with the British laws, the offender is indicted before the lord mayor, and must take his trial as any other English subject.

When questions of general importance are agitated, the gaboy, or treasurer, summon the elders to monthly meetings; where, in conjunction with the wardens, the subject is discussed, and decided by a majority. If the votes are equal, the president is allowed the casting vote in addition to his own; but all resolutions passed at one meeting must be confirmed in the next, to be considered valid.

No member of the synagogue can be an elder, unless he has served or been elected a warden or treasurer; but there are some meetings to which, in the Spanish congregation, all the members of the synagogue are summoned, women as well as men; all, in short, of either sex who pay a tax to the synagogue; the paying of which tax, or finta, as it is called, constitutes a member. There is no fixed assessment, but each member is taxed according to his means.

These remarks, however, refer principally to the Spanish and Portuguese congregation; the Dutch and German differs in some minor points, such as having three wardens instead of four, who serve sometimes two years instead of one. And in addition to the wardens and treasurer, they have an overseer of the poor and seven elders, who are annually elected from the members of the vestry, and regularly attend at monthly or vestry meetings; forming, with the honorary officers, wardens, &c. a committee, who deliberate on all matters essential to the congregation. The vestry of the Germans, like the elders of the Portuguese, consists of such members as have previously been elected to the honorary offices. Their duty is to attend all special and quarterly meetings for the general government of the synagogue.

In both synagogues, Spanish and German, all members residing within twelve miles of the synagogue are eligible for either of the honorary offices, and are elected by ballot; the president in this, as in other cases, having the casting vote. No election is considered valid without a majority of seven votes. The individual elected may or may not accept, but is subject to a fine if he refuse, unless incapacitated for the duties of the office by ill health or old age. Persons above seventy years of age are exempted from the fine.

In London, we might almost say in England, there is but one Spanish and Portuguese synagogue; that founded by Menasseh Ben Israel in the time of Cromwell. The Germans have so multiplied, that not only have they four or five synagogues in London, but form a congregation in almost every provincial town. It is a rare occurrence to find a family of Spanish or Portuguese extraction established elsewhere than in London; but wherever the Germans can discover an opening for business, there they will be found active and persevering, self-satisfied and happy; ever on the alert for the increase of wealth, and not over-scrupulous as to the means of its acquirement. The synagogues and Jewish congregations, therefore, in the provincial towns, it should be remembered, all belong to this body, and must not be considered as representatives of all the British Jews. Each synagogue belonging to the Germans has its own government of honorary officers, &c. who superintend the affairs of their own congregations, rich and poor. Formerly they were all considered tributary to the great synagogue of Duke's Place; but they are now independent, and the bond of union being one of amity and not of restraint, their individual and several interests have been preserved in mutual harmony.

In addition to the already-mentioned officers, each synagogue has two or more deputies, elected every seven years, as representatives of the Jewish nation to the British government. Their duty is to take cognisance of all political and statistical matters concerning the Hebrew communities throughout the British empire. In cases of general national importance, they meet together, consult, and then reporting the result of their deliberations to their elders and constituents, for such in fact are the several congregations by whom they are elected, and, receiving their assent, they proceed to act on the measures proposed. On all occasions of public rejoicing, as in the accession of a sovereign or national victory, &c. it is the office of the deputies to address the sovereign in the name of all their brethren; and in cases of petitions for increased privileges for themselves, or relief for their oppressed nation in other lands—as at the time of the Damascus persecution, or the recent Russian ukase—it is their duty to wait upon the premier, or any of the ministers in office, and request their interference.

Jews of Continental Europe.

n the treatment of the Jews, Great Britain at present occupies a position between the United States of North America, France, and Belgium, on the one hand, and Germany and Russia, with some other countries, on the other. In the United States, Jews are eligible to all civil offices; and there it is far from uncommon to find Jews performing the functions of judges of the higher courts, sheriffs, and members of congress. All this is exactly as it should be. InFrance, Jews are likewise eligible for civil offices without violation of conscience; and also in Belgium, the Jews are not proscribed in the manner they too frequently have been.

Religious toleration cannot be said to extend farther in continental Europe than through France and the Netherlands. As respects the treatment of Jews, most continental nations are still less or more floundering in the darkness of the middle ages. In many nations the Jews are still liable to insults, oppressions, banishment, and even at intervals to torture and massacre. The same charge of kidnapping and murdering Christian children is in Poland, Prussia, and many parts of Germany, constantly fulminated against them—rousing the easily-kindled wrath and hate of the more ignorant, and occasioning such assaults as frequently demand the interference of the military to subdue—and the subsequent discovery that the supposed victim of Jewish bloodthirstiness has fled from the cruelty of Christian masters, found refuge, and kindness, and food in the Jewish households, to which he may have been tracked, and escaped thence, with their friendly aid, into the open country, where, happily for the release of his benefactors from unsparing slaughter, he is discovered and brought back. Repeatedly, however, as this occurs, and not only the innocence but the benevolence of the Jews publicly established, it has no power to prevent the repetition of the same charges whenever a Christian child disappears: a perseverance in prejudice and perversion of humanity scarcely credible in the present day, but proved only too true by the constant witness of the continental press.

It is very difficult to obtain a just and correct view of the domestic history of the Jews on the continent: scarcely possible, in fact, except by a residence of some weeks in the midst of them. Travellers notice them so casually, and these notices are so coloured with the individual feelings with which they are viewed, that we can glean no satisfactory information except as to their social position, which has been always that of a people apart. The less privileges they enjoy, the more marked of course this separation becomes. The prejudice on both sides is strengthened; and to penetrate the sanctuary of domestic life and their national government, is impossible. In France and Belgium, as we have seen in England, they are only Jews in the peculiar forms and observances of their religion: in everything else of domestic, social, or public life, they are as completely children of the soil as their Christian brethren. Elsewhere on the continent, they are so marked by degrading ordinances, even to their modes of dress, and the localities of their dwellings, that their individual and social identity is known at once, and they are shunned and hated as possessors of the plague. In Rome, the Jews are still con fined to one quarter of the town, called the Ghett, which several months in the year is so completely inundated, as only to permit egress and ingress by means of boats. In the other towns of Italy, though the quarters of the towns assigned them may be somewhat less unhealthy, their social position is the same. In Austria, though Francis I, and after him Joseph II, sought to meliorate their condition, the endeavour does not appear to have been continued; for the humiliating and distressing liabilities to which they are subject in the empire have degraded them to the lowest ebb, and, except in a very few instances, utterly prevent their raising themselves, either socially or mentally. It so chanced, however, that a wealthy Jew did obtain such favour from the emperor, in return for some weighty service, as to be offered a patent of nobility, which, with a nobleness of soul needing no empty title to make it more distinguished, he refused, asking in its stead freedom of the city for his sons in-law (he had no sons, and his daughters were then unmarried). It was granted; and the gift of his daughters obtained for their fortunate possessors a privilege granted to none other: for the sons-in-law of this honourable Jew are the only free Jewish citizens and merchants of Vienna.

In the time of Napoleon, several of the smaller German sovereignties befriended the Jews, issuing ordinances admitting them to many civil rights, exempting them from oppressive imposts, and permitting them to pursue trade and obtain professorships. In gratitude for these unusual privileges, several entered the army of the allies, formed in 1813 to break the galling yoke of Napoleon, and so distinguished themselves, as to receive as many medals and decorations of honour as their more naturally warlike compatriots. It was only reasonable that, as they performed all the duties of patriots and citizens to their respective states, they should demand and expect the abolition of all the oppressive enactments made against them in more barbarous times. And we find, in 1815, the Germanic Confederation assembled at Vienna, declaring in their sixteenth article, “The diet will take into consideration in what way the civil melioration of the Jews may best be effected, and in particular how the enjoyment of all civil rights, in return for the performance of all civil duties, may be most effectually secured to them in the states of the Confederation. In the meantime the professors of this faith shall continue to enjoy the rights already extended to them.” From the present condition of the Jews in Germany, however, this would appear mere words. With the cessation of the call for their patriotism from the general amnesty, the recollection of their services also ceased, and no decided means ever seems to have been taken to secure to them the promised privileges. The great trading towns, Hamburg, Lubeck, Bremen, and especially Frankfort-on-Maine, never showed even the profession of friendliness towards them. The jealousy awakened by that spirit of commercial enterprise, so peculiarly a Jewish characteristic, continues still, and effectually retards their social consideration; rivalry in commerce being unhappily as great a fosterer of prejudice as the ignorance of former years. In Frankfort, until a very few years ago, so heavily were they oppressed, that if any Jew, even of the most venerable age, did not take off his hat to the mere children of Christian parents, he was pelted with stones, and insulted by terms of the grossest abuse, for which there was neither redress nor retaliation; and this was but one of those social humiliations, the constant pressure of which must at length degrade their subjects to the narrow mind, closed-up heart, and sole pursuit of self-interest of which they are accused. The impoverished condition of the nobles and princes of the soil, during the late war, frequently compelled them to part with their estates to the only possessors of ready money—the Jews. When the immediate pressure of want had subsided, it was naturally galling to men, as proud as they were poor, to behold the castles and lands, the heritage of noble German families through many centuries, enjoyed by men of neither rank nor education, and whose sole consideration was great wealth. The very means by which that wealth was obtained—contracts entered into with the French emperor—increased the dislike of all classes towards them, heightened by the presumption and ostentation they displayed. In 1820 riots broke out against them at Meiningen, at Wurtzburg, and extended along the Rhine. Hamburg, and still farther northward, as far as Copenhagen, caught the infection; and so serious were the disturbances, so sanguinary the intentions of aroused multitudes, that it demanded the utmost vigilance of the various governments to prevent the nineteenth century from becoming a repetition of the twelfth, thirteenth, and fourteenth centuries. The very cry which was the signal for the old massacres, and which, once heard, was as certain doom to the hapless Jew as if the sword was already at his throat—“Hep! hep!” from the initials of the old Crusade cry, “Hierosolyma est perdita!" [“Jerusalem is lost!”]—was revived on this occasion; a curious fact, as full four centuries had elapsed since it had last been heard. Nine years later, we are told that “when the states of Wirtemberg were discussing a measure which extended civil rights to the Israelites, the populace of Stuttgard surrounded the Hall of Assembly with savage outcries of ‘Down with the Jews!” The states, however, calmly maintained their dignity, continued their sittings, and eventually passed the bill.”

When we remember that this fanatical outbreak of prejudice took place scarcely twenty years ago, we may have some idea of the social position of the Jews in Germany. Notwithstanding its humiliating nature, however, they have shared the advancement of the age in the zealous cultivation of intellect and art. The extraordinary genius of their great countryman, Moses Mendelsohn, who flourished in the eighteenth century—the boldness with which he had flung aside the trammels of rabbinism, and the prejudices arising from long ages of persecution, making himself not only a name amongst the first of German literati, but forming friendships with Lessing, Lavater, and other great spirits of the age, completely destroying in his own person the unsocial spirit of his nation--had given an impulse to the Jews which even the excitement of the war, and its vast resources for amassing wealth, had not the power to diminish. German, and the other modern languages, which, until the master-mind of Mendelsohn appeared, had been considered profane, and therefore neglected, are now zealously cultivated, the literature of each appreciated and studied. They attend the universities, and have greatly advanced in all the departments of mental and physical science; thus proving that when the Jews appear so devoted to interest alone, as to neglect all the higher and more intellectual pursuits, it is position, not character, that is at fault. In the earlier ages we find them, in the brief intervals of peace, not merely merchants of splendour and opulence, but the sole physicians, sole teachers, sole ministers of finance in their respective realms to nobles and princes. Their superior intelligence and education at a period when it was rare for nobles and kings, and even the clergy, to write their names, marked them out for offices of trust, which they never failed to execute with ability and skill. And it is notorious that the ambassador between the Catholic Emperor Charlemagne, and the no less famous Mohammedan potentate Haroun al Raschid, holding in his sole trust the political interests of Europe and Asia—for at that time the princes we have named might be justly considered the representatives of the two continents—was neither knight, noble, nor prince, but simply Isaac, a Jew! But when these breathing-times had passed, when kings and princes needed wealth, and their exhausted coffers could only be replenished by the treasures of the Jews— when the multitude asked but a rumour to fan suppressed hatred to a flame—the horrors of persecution recommenced; the services of the Jews were forgotten; and statute after statute, each more degrading than the last, bound them to such a position, such pursuits, that they became ignorant of their own power themselves, and made no effort to prove themselves other than they were believed. But the power was quenched—not lost; and it is bursting forth again with renewed vigour wherever it has scope for development and growth. There is a street in Frankfort-on-Maine called the Juden Strasse, or Jews Street, in which the houses look so aged and poverty-stricken, that to walk down it almost seems to transport one to the middle ages, and recalls all the painful stories of the Jews of that time, and the marvellous tale of the lavish splendour and great wealth which these hovel-like entrances concealed; the affectation of poverty and abject misery assumed, not from any miserlike propensities in themselves, but to deceive their cruel foes, to whom the scent of wealth was always the signal for blood. In this street, during the late war, dwelt an honest, hardworking Jew, little regarded by his fellows of his own or the Christian faith; he was poorer than the generality of his brethren, and there was nothing in his appearance or manner to denote a more than common mind. How it happened that he was selected as the guardian of certain monies and treasures belonging to a German prince, whom the fate of war had caused to fly from his possessions, does not appear; but certain it is that the trust was willingly accepted and nobly fulfilled. The confusion and alarm of the French invasion, and the various revolutions in Germany thence proceeding, extended to Frankfort. Many of the Jews were pillaged; for wealth being imagined synonymous with the word Jew, they were less likely to escape than any. The Jew we have mentioned was amongst the number, but so effectually were the prince's treasures concealed, that their existence was not even suspected. And when the tumult had ceased, and Frankfort was again left to its own quiet, the Jew’s own little property had greatly diminished, but his trust was untouched. Some few years passed; the pillaging of Frankfort had reached the ears of the dispossessed prince, and he quietly resigned himself to the belief that his own treasures had shared the common fate, or at least had been appropriated by the Jew to atone for his own losses. As soon as he could, he returned to his country, but he was so fully possessed with the idea that he was utterly impoverished, that he made no effort at first even to inquire after the fate of his property. His astonishment—which, however, admiration and gratitude equalled—may be conceived when he received from the hands of the Jew the whole untouched; some assert with the full interest of certain sums which his necessities had compelled him to use; but this is traditional. We can only vouch for the truth as far as the immediate undiminished return of the whole property as soon as claimed. The effects of this honourable conduct can be traced to this day in the whole financial world.

The prince was not of that easy nature to be satisfied with the mere expressions of gratitude. He spread the tale—which, regarded as an utter contradiction to the imagined characteristic usurious practices of the Jews, appeared far more extraordinary than it really was—over all the courts of Germany. From them it spread to other kingdoms: the Jew found himself suddenly withdrawn from obscurity, and all his talents for financial enterprise—of the extent of which, perhaps, he had been ignorant himself till the hour found the man—called into play. Not only did he amass such wealth himself as perhaps sometimes to cause a smile at the treasures which had seemed of such moment to their owner, but his family, ennobled, accomplished, prince-like in their establishments and position, may be found scattered in almost every European court, and acknowledged on every Exchange as the great movers of the money market of the world. Put the widow of their founder, now nearly a century old, refuses all state or grandeur: she receives the visits of her descendants, but in the same lowly dwelling that beheld the rise and growth of her husband's fortunes—in the old dilapidated Juden Strasse of Frankfort.

While Poland was an independent sovereignty, the Jews there had greater privileges than in any other European kingdom except Spain; and in fact many Spanish and Portuguese refugees fled to that country when expelled from their own. A charter is still extant, made by Duke Bodislas, who flourished in the thirteenth century, protecting them from oppressions of every kind, and breathing a spirit of toleration and benevolence strangely contrasting with the cruel enactments of contemporary sovereigns. The love said to be borne by Casimir, the great grandson of Bodislas, for a Jewish girl, occasioned the confirmation of this deed. And even when, at a later period, and in the first heat of the controversy between the Catholics and Protestants, the latter faith was prohibited, the Jews still remained unmolested. They formed the only middle class of the kingdom, and, as such, were the sole engrossers of traffic, constituting in several towns and villages nearly the whole of the population. They had numerous academies, where, however, the rabbinical, more than general learning, was made a first object. Poland might at that time have been termed the seat of rabbinism, for nowhere were the traditions more considered, nor its teachers more revered. Jewish parents from all quarters sent their sons to the Polish schools, satisfied that there they must attain all the necessary knowledge.