Michael Gibbons kindly provided us with this column from Harper's Weekly, which deals first with Owen Seaman's parody of The Eternal City. Owen Seaman (1861-1936) was the editor of Punch from 1905-1932, but, having been taken on in 1894, was already responsible for much of its comic verse, and such spoofs as these. Parody was his special forte. However, the columnist goes on to report the triumph of the novel's theatrical adaptation, both in England and America, and, after some more theatre news, to talk amusingly about novel reviewing. This may or may not have some bearing on the the kind of criticism to which, the columnist says earlier, Hall Caine had been subjected. — Jacqueline Banerjee

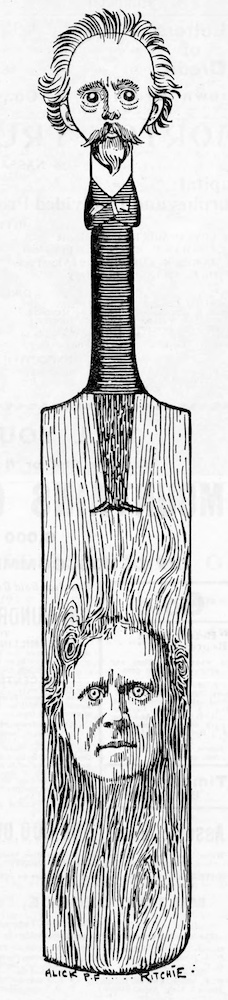

"This is the tree that grew the Ca[i]ne." Hall Caine, the author

and dramatist of The Eternal City, and Beerbohm Tree,

who has produced the play in London.

(Signed by Alick P. F. Ritchie.)

One of the cleverest parodies in Mr. Owen Seaman’s Borrowed Plumes, just published, is the burlesque on Mr. Hall Caine’s latest novel, The Eternal City. David Rossi becomes Deemster Dotti, whose motto is “Everything for everybody else!” “Daniel Leonidas,” he tells Athena of the mulberry eyes, was his baptismal name. “Dotti is an alias.” "Never mind, dear,” cried Athena. “To me, whatever your real name, you will never be anything but dotty!” She smiled shyly at her own wit, we are told, and flung herself upon his answering chest. The Epilogue is finely hit off in this fashion:

It was a summer evening. Kaspari’s work was done. Beside his cottage door, on the hills above Megara, the fine old shepherd was sitting in the sun. He had just returned from Athens, after a one-day excursion.

“Papotis!” (grandpapa), cried little Petrokinos, "what is that you have in your pocket, so large and smooth and round?”

My child,” replied Kaspari, “’tis a present from Athens for a good boy. ’Tis a bit of the Bust of the great Dotti!” ...

“Who was Dotti, grandpapa?”

“Dotti, my boy? Why, that’s ages ago, back in the early part of the twentieth cen- tury, before they did away with Kings and Boundaries, and such-like relies of barbarism.”

“Is it a pretty story, grandpapa?” asked the boy, wistfully.

“That’s a matter of taste, my child,” replied the old man; “but I know it’s a d—d long one.”

The Eternal City, dragging out its dreary length through an inky waste of over six hundred pages, may be a dull story, but its theatrical adaptation seems by all accounts to present a strong and interesting drama. The splendid spectacular presentation of the stage version by Mr. Beerbohm Tree and his excellent company of players at His Majesty’s Theatre in London is a veritable triumph for Mr. Hall Caine, after the derision and abuse hurled upon the metropolitan production of The Christian. Many of the critics are still sceptical, and refuse to be won, but what cares Mr. Hall Caine, for has he not captured the greatest theatrical management in London? Has he not con- quered the Great Public? Tidings also come from Washington that a similar success has crowned the efforts of the author and dramatist of The Eternal City in this country. Here Miss Viola Allen is the Roma of the novel; in London the character is impersonated by Miss Constance Collier, and in the English provinces by Miss Maud Jeffries, who played Mariamne to Mr. Tree’s Herod in Stephen Phillips’s poetic drama. One foresees a wild orgy of Weber - Fieldian burlesque in the near future. Mr. Hall Caine is due in New York on the arrival of the Lucania at the end of the week.

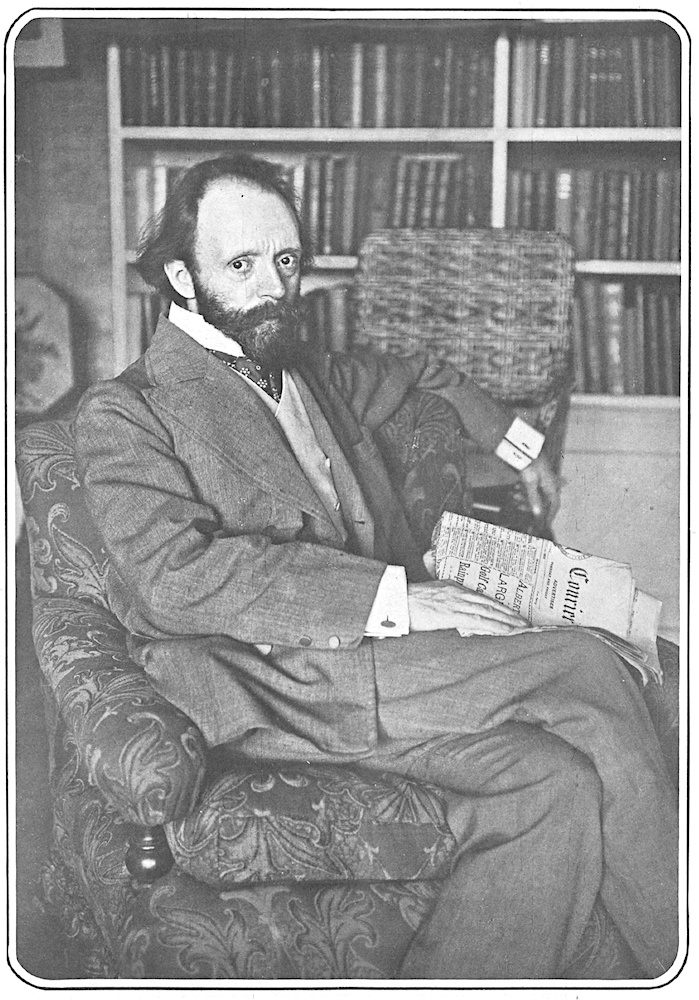

Mr Hall Caine, the distinguished author and playwright, who has just arrived in America to supervise the production of the dramatization of his nove, The Eternal City, in New York (p. 1536 of the same issue).

Mrs. Edith Wharton, in a recent number of the North American Review, notes the almost simultaneous production of three plays on the subject of Francesca da Ri, by playwrights of three different nationalities, as illustrating in an interesting manner that impulse of the creative fancy which so often leads one imaginative writer to take up a theme already dealt with by another. To this we may add another curious coincidence of this simultaneous cerebration, also by playwrights of three different nationalities, on the subject of Mary of Magdala. It has been made public that Mr. Stephen Phillips is engaged on a poetic drama of the Magdalene, for Miss Julia Marlowe; also that Mrs. Fiske will open shortly with a translation of a play by Paul Heyse, the German novelist and dramatist, on the same theme. But before these announcements were made, Miss Florence Wilkinson, well known as the author of The Strength of the Hills, had conceived and written out the scenario of a play called Mary Magdalene. We understand that Miss Wilkinson has since completed her drama, and as it is very effective in dramatic treatment and construction, it is likely to be produced by some aspiring. actress desirous of rivalling Miss Marlowe and Mrs. Fiske. Both in the case of Francesca and the Magdalene, the dramatists have had free play of imagination in creating their own story, for with the exception of the climactic situation about which the dramatic action revolves, no definite outline or fable or historical data exist to account for the central facts of these dramas — one being the apotheosis of a great human passion, unrepented; the other, of a great divine love, consummated in repentance.

A reviewer, who finds his occupation held up to odium by the authors whose especial grievance is the brief notice, has this to say in his defence: "The brief notice, these authors say, is written by a man who reads half a dozen pages of the novel, three at the beginning and the three at the end, and thus disposes in a few minutes of the toil of many months. Sir, you may desire to publish my portrait when I tell you that I read every word. There is for me a weird fascination even in a poor novel. I read on with growing wonder that the writer had the moral energy to persevere to the last chapter. But the point is that the reviewer in most cases should be able to state his impression of a novel in twenty lines. People who say this cannot be done are not acquainted with the art. William Black used to affirm that the reviewer’s opinion was not worth having, because he could not know the processes of the novelist’s mind. But he does know the results, and for the purpose of judgment he can put them in a very small compass. Twenty lines, sir, are enough for the ordinary novel, though twenty thousand might fail to disclose the whole nervous commotion that produced it.”

It is true, nevertheless, that the reviewer is often a hardened expert with an incurable bias, a warped mind, a once kindly disposition turned to malevolence by the reviewing of books, of which there is no end. We sometimes hear it questioned whether reviewing has any influence nowadays on the circulation of books. If it has not, then the root of the evil may lie in the prevalence of the professional reviewer, with his set mind, his cast-iron methods and stock phrases, though much of it may be attributed to the sophomoric drivel that finds its cheap way into print only to take the name of literature in vain. It has been suggested that a revolution might be wrought in this direction by intrusting the task of reviewing to fresh and untried enthusiasts to whom novel-reading is a constant renewal of the heart’s best emotions.

Failing this, there seem but two alternatives before us. Let the author himself review his own book. He can best be trusted to discuss the story with understanding of its motives and action, revealing all that is most likely to lure the reader, and concealing so much of the plot (though Heaven knows there is little plot to most of them) as is necessary to the element of suspense. Another way to meet this author’s peril is to agitate for the development of the Californian “law of privacy” in literature. Let it be a penal offence to review a novel without a certificate from the author that the critic is a fit and proper person to classify the beauties of the work.

Bibliography

"Books and Bookmen." Harper's Weekly. 18 October 1902: 1513.

Created 2 October 2022