[Thanks to James Heffernan, founder and editor-in-chief of Review 19 for sharing this review with readers of the Victorian Web. — Katherine Miller Weber]

riting about Dante Gabriel Rossetti has never been simple. The incidents of his life promise a good narrative and have tempted many writers. But Rossetti the artist and Rossetti the poet have always been there first. His early prose fable "Hand and Soul" announced, before the drama of Pre-Raphaelitism's tangled relationships was well begun, that the artist's hand must itself trace the outlines of its own soul if it is to create art that speaks lastingly to others. As if that were not clear enough, ten years later, introducing his translation of Dante Alighieri's Vita Nuova, Rossetti pointed out that the work's stylized and deeply mythologized history of the poet's early life was an "auto-psychology": at once a vision and a study of the soul. Unlike an autobiography that seeks to explain a life already lived, both the fictional artist Chiaro's painting of his Anima (in "Hand and Soul") and Dante's analysis of himself in love (in his Vita Nuova) are prospective, the visions of men who looked inward to find through soul-study the myths and images through which to interpret the soul for their times. As the young Rossetti seems already to have grasped, the visionary works such soul-study produces will themselves shape not only the works that the poet or painter goes on to create but also the lives each has yet to live. Rossetti's own Vita Nuova was "The House of Life": at once a gallery of soul-paintings and the poetic psycho-graphy of a modern subject offered as a guide (however indirect) to the experience of human love in his own times. As with Dante and the fictional Chiaro, "The House of Life" both witnessed and continued to exert the power of image and myth to shape, in turn, the lived life.

riting about Dante Gabriel Rossetti has never been simple. The incidents of his life promise a good narrative and have tempted many writers. But Rossetti the artist and Rossetti the poet have always been there first. His early prose fable "Hand and Soul" announced, before the drama of Pre-Raphaelitism's tangled relationships was well begun, that the artist's hand must itself trace the outlines of its own soul if it is to create art that speaks lastingly to others. As if that were not clear enough, ten years later, introducing his translation of Dante Alighieri's Vita Nuova, Rossetti pointed out that the work's stylized and deeply mythologized history of the poet's early life was an "auto-psychology": at once a vision and a study of the soul. Unlike an autobiography that seeks to explain a life already lived, both the fictional artist Chiaro's painting of his Anima (in "Hand and Soul") and Dante's analysis of himself in love (in his Vita Nuova) are prospective, the visions of men who looked inward to find through soul-study the myths and images through which to interpret the soul for their times. As the young Rossetti seems already to have grasped, the visionary works such soul-study produces will themselves shape not only the works that the poet or painter goes on to create but also the lives each has yet to live. Rossetti's own Vita Nuova was "The House of Life": at once a gallery of soul-paintings and the poetic psycho-graphy of a modern subject offered as a guide (however indirect) to the experience of human love in his own times. As with Dante and the fictional Chiaro, "The House of Life" both witnessed and continued to exert the power of image and myth to shape, in turn, the lived life.

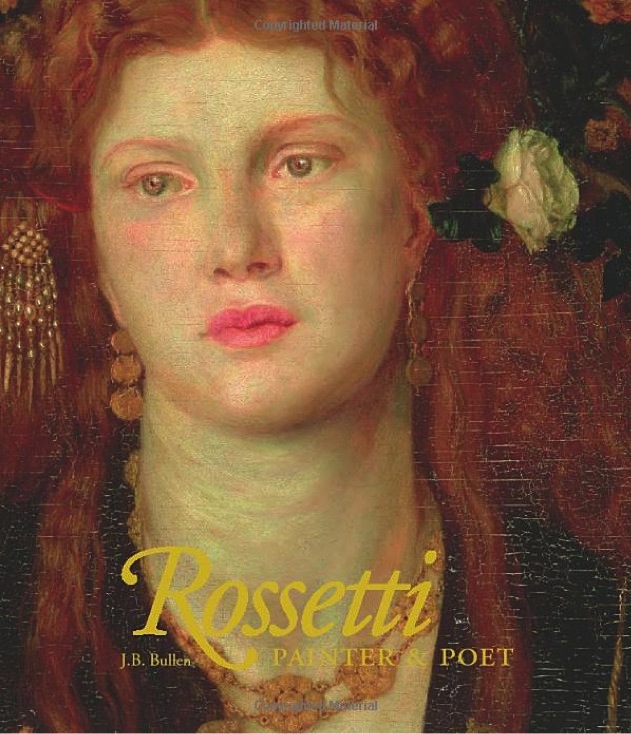

In J. B. Bullen, whose new book studies "Rossetti's painting and poetry in the context of the drama of his life" (9), Rossetti has a highly sympathetic collaborator in the psycho-graphic project. This large-format, generously illustrated book, meant for the general reader as much as the scholar, is distinguished less for any new research than for the skill with which Bullen interprets both Rossetti's poems and, especially, his pictures in light of a single strong thesis — a vision, as it were, of Rossetti's Anima. The modern subject brilliantly limned in Rossetti's painting and poetry, Bullen argues, is above all a psycho-sexual subject. "The driving force of his imaginative experience was erotic desire and the part that desire played in life" (9). "The whole tendency of Rossetti's imaginative drive was to find ways of representing erotic desire and explore the central part it plays in both personal life and human history. In this quest the female form was the central element in his imaginative vocabulary" (211). The great achievement of "The House of Life" was to generate "an original symbolic vocabulary of emotions" (260) in which the art and poetry are taken together as a single autographic project. Bullen concludes that "what he had constructed both for his contemporaries and for the generations that followed was essentially a carefully plotted map of the structure of the emotional life, an anatomy of desire" (261).

This is clear enough and often memorably phrased. Bullen's argument draws on his earlier detective work in a series of subtle historical contextualizations of British nineteenth-century responses to art, especially art that challenged conventions of representing desire; I refer to Bullen's The Pre-Raphaelite Body: Fear and Desire in Painting, Poetry, and Criticism (1998) and some of the essays in his Continental Crosscurrents: British Criticism and European Art 1810-1910 (2005). Bullen is an excellent guide to Rossetti's painting of the 1860s and 70s and to the "drama" of the lived life, both examined perceptively in light of his central generative insight. The book offers fine interpretive descriptions of Fazio's Mistress, Lady Lilith, Proserpina, and many, many others while commenting interestingly, inter alia, on Rossetti's fraught relationship with his father, Gabriele; on the stimulus to desire Rossetti found in triangulated love affairs, beginning with the pleasures of "sharing" a mistress with his good friend George Boyce; and on the influence first of Botticelli and then of Michelangelo (with whom he came to identify as another painter-poet, in the last decade of his life) on his visual and verbal symbolic vocabularies for psycho-sexual emotions. Bullen makes impressive use of the late correspondence with Jane Morris for his account of Rossetti's post-breakdown emotional life and the correlative changes in his visual imagery for that life in the later 1870s. He observes, I think correctly, that Rossetti's last paintings modeled from Jane Morris continue to explore new passages in the development of a long relationship.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, The Day Dream (1880).[Click on image to enlarge it.]

"The Day Dream," Bullen writes, "forms one part of a cluster of highly personal, final paintings that celebrate Rossetti's many-sided relationship with Jane extending from loving intimacy, to awe in the presence of her sexual power [as in Astarte Syriaca, 1877], and from physical desire to emotional dependency [as in La Donna della Finestra (The Lady of Pity), 1879]" (254). Late love's kindness, the balm of a continuing though distanced friendship, is perhaps most clearly registered in the latter painting but also evident in a late version of The Salutation of Beatrice (1880-81). For two decades Rossetti's painted work had consisted primarily of these single images of women. Bullen's nuanced, psychologically perceptive readings allow us to better appreciate them not as repetition but as an emotional history, a self-study of love as an ongoing, shifting, psycho-sexual experience that continued to evolve right up to Rossetti's death.

At its best, then, Bullen has written a kind of prose "House of [Rossetti's] Life," reversing the transfiguring process of abstracting personification and sensuous re-figuring described by Jerome McGann (in his Rossetti Archive on-line commentary [outside the Victorian Web], and elsewhere) and before him Veronica Forrest-Thompson ("From Lilies from the Acorn," Chicago Review [outside the Victorian Web]) and of course, Rossetti himself (H of L Sonnets LX, LXI: "Transfigured Life" and "The Song-Throe"). In his frequent references to Rossetti's poetry, Bullen can illuminate the emotional tone and imaginative drive of desire behind a given passage, but I found his commentary somewhat disappointing as an account of what might give it poetic distinction. The poems are indeed made to "speak" the paintings (the juxtapositions are often telling), but not, perhaps, to say enough about themselves. Art historians, too, will need to look elsewhere (to Elizabeth Prettejohn's various studies, for example) for fresh light on Rossetti's complicated stylistic relationship to the modern art that rejected him (though Bullen usefully comments on his negative response to his contemporary, Manet).

The visual layout of this volume makes an interesting departure from what might be expected of the art book that the publishers evidently designed it to be. Beautifully reproduced images of Rossetti's art works form an essential part of the argument elaborated in the adjacent text on each page. But more unusually, prominence is also given to images of the poetry: selections set in large type (usually four to eight line passages, occasionally an entire sonnet) are arranged, like the paintings, to the left or right of the main text rather than within it. In effect, the poems have been treated like pictures. This arrangement allows the book to function something like a modern illustrated lecture (where digital projection lets the audience consider the works in question while listening to what the lecturer has to say). Or perhaps the model is the on-line blog — as indeed a visit to Bullen's well-designed website [outside the Victorian Web] seems to confirm. Links direct us to four such "Blogs": sequences of images, of both pictures and poems, linked by minimal narrative so that the images bear most of the weight of the argument. These are archives assembled and arranged, we are told, for the lecture courses the energetic Bullen has been offering at various places since his retirement from the University of Reading in 2005. While the text of his critical book is certainly much richer than that of the online blogs, both projects respect the power of poems and paintings to constitute a form of argument of their own.

In this respect Bullen's Rossetti does indeed, as he wishes, "pay tribute to the scholarship of . . . Jerome McGann" (4). Yet his conception of the critical study (or at least, of this book) differs strikingly from that of McGann's Dante Gabriel Rossetti and the Game That Must Be Lost (2000) or from Jan Marsh's 1999 biography, the other recent book Bullen singles out for special acknowledgment. Taking as critical model Rossetti's scheme for an unexecuted painting, "Venus surrounded by mirrors," McGann makes the chapters of his slim volume reflect (on) Rossetti from multiple perspectives. The same generous principle of multiplicity inspires the online Rossetti Archive [outside the Victorian Web]. For Marsh, too, Rossetti is a peculiarly complex figure whose originality and impact on British and European painting have suffered from the temptation of earlier critics to simplify him. Bullen's study, however, is quite tightly focused, perhaps because it represents convictions developed over a long life of scholarship, or perhaps simply because it is intended for a larger audience. It does indeed illuminate a central aspect of Rossetti's originality and influence. In more than one meaning of the term, his book makes sense of the paintings and poetry when they are read with the drama of Rossetti's life. And yet, returning to Rossetti's work, one cannot help reflecting that the price of imposing coherence — of using a single interpretive key — is also high.

Related Material

- Laurent Bury's review of Rossetti, Painter and Poet

- Pre-Raphaelites: An Introduction

- Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882): An Overview

- Rossetti's Real Fair Ladies: Lizzie, Fanny, and Jane

Bibliography

J. B. Bullen Rossetti: Painter and Poet. Frances Lincoln, 2011. 272 pp.

Last modified 5 July 2014