Fox Cooper's 1860 Adaptation of Charles Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities (1859) as Staged at The Victoria Theatre, London (July 1860): From Tragedy to Melodrama

When Charles Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities finished its serial run in December 1859, it was as a matter of course adapted a number of times for the stage. Although the most successful and — in terms of later cinematic and television adaptations — the most influential stage adaptation was The Only Way by the clergymen Freeman Wills and Frederick Langbridge (commissioned by John Martin-Harvey, the actor-manager who would make the part of Carton his own for the next thirty-six years) in 1899, the first, "authorised" and even supervised by Dickens himself, opened at London's Lyceum Theatre on the 28 January 1860.

Despite its ending anticlimactically with the death of Madame Defarge rather than with the triumphant self-sacrifice of Carton (played by Fred Villiers), the play had a respectable run of thirty-five performances. Dickens's collaborator in the venture was none other than "the reigning dramatist of the early 1860's" (Morley 34), Tom Taylor (1817-1880). This writer's prolific output includes material for Punch, and such plays as Our American Cousin (the comedy that President Lincoln was watching at Ford's Theatre in Washington when he was assassinated), and the melodrama The Ticket-of-Leave Man (1863), which champions the cause of the ex-convict and attacks society's biases which prevent his rehabilitation. Taylor was, like Dickens, an enthusiastic and talented amateur actor, having played in the novelist's specially-erected private theatre at Tavistock House. Taylor's adaptation, a prologue and two acts (56 pages), licensed 20 January 1860 by the Lord Chamberlain's office, was duly published by Lacy in Great Britain and Samuel French in the United States.

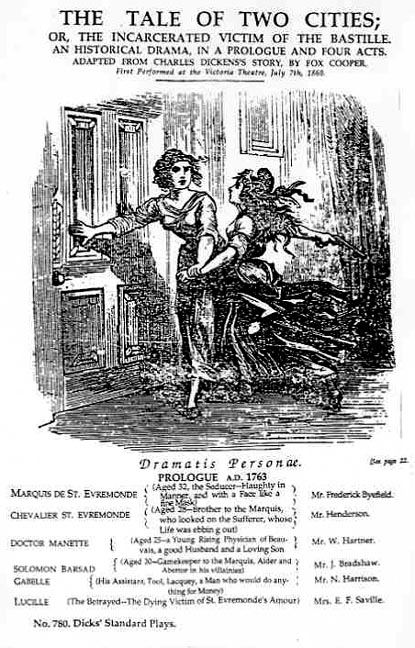

However, the version published as No. 780 in Dicks' Standard Plays (London), the fourth such adaptation, according to Philip Bolton in Dickens Dramatized (1987), was somewhat longer at 62 pages in ms. (twenty-two double-columned pages in Dicks), consisting of a "Prologue" in two scenes dramatising events of 1763 (in the novel, 1757), and four acts. Entitled The Tale of Two Cities; or, The Incarcerated Victim of the Bastille, this blend of historical extravaganza and melodrama opened on 7 July 1860 at London's Victoria Theatre, another of those houses south of the Thames that catered primarily to working-class audiences by providing thrilling melodramas. Located opposite Waterloo Station, it was less than a block away from the Surrey Theatre. This adaptation had W. H. Pitt in the leading role supported by Mrs. Charles Boyce as Lucie, W. Harmer as Doctor Manette, Howard as Mr. Lorry, Raymond as Darnay, and Frances Harrison as Miss Pross. An interesting twist is that Mrs. E. F. Saville doubled as the scheming, villainous "Therese" Defarge and her pure, abused sister Lucille, "The Betrayed — The Dying Victim of St. Evremonde's Amour," as the Dicks title-page describes her. Apparently, staging was lavish, for the play had a running time of over three hours, and featured forty-two speaking parts, making it as much extravaganza as melodrama. In the Taylor adaptation, all the scenes are laid in Paris; in Cooper's version, Act Two alone is set in London. Cooper has also elected to cover Darnay's Old Bailey trial in dialogue in the first act, and (again as in Taylor's) have Madame Defarge accidentally killed by her own pistol. However, the "official" adaptation has her die while she is struggling with her husband as he attempts to prevent her from leaving to denounce Darnay to the Tribunal. Nevertheless, Cooper's adaptation largely follows the novel's original text.

Significantly, however, "The Prologue" markedly alters Dickens's construction of the narrative. Cooper eliminates the complication of the embedded first-person account, Dr. Manette's hidden letter, the plot secret revealed in Book Three, Ch. 10, that at a crucial moment seems to seal the fate of Charles Darnay. Dickens's withholding of the flashback in the novel serves the create suspense, but Cooper's initially revealing the cause of Madame Defarge's inveterate hatred of the St. Evremondes unravels the story's complications to create a more coherent dramatic text.

Suspense and poetic justice characterize the conclusions of both Cooper's and Taylor's adaptations, which possess in abundance what Carol Hanbery MacKay terms the "predominantly melodramatic orientation" of Victorian drama. All too often Dickens's subtlety is discarded in favour of the sensationalism characteristic of melodrama, as is evident in Fox Cooper's lurid handling of the murder of the Marquis, which occurs partly on stage at the close of the third act, and involves a brutal assault by Gaspard (Jacques 5), Jacques 1 and 2, and Madame Defarge, whose vaunting speech is the harbinger of the excesses of the September Massacres:

Mad. D. Shouts to celebrate the downfall of your race. The peasant — the scorned dog — assails your walls! Why crouch there, like a worm, while the dogs storm your places of strength? They are fast rising, and a signal shall soon warn the people to press hard upon those who would extinguish them! And now, murderer, farewell for ever! May every stone of this roof, as it falls upon you, find a tongue to echo that name in your ear! [Exit through door, locking after her. — As the Marquis rushes up to leave, GASPARD, or JACQUES 5, appears from behind, and seizes him by the throat, brandishing a large knife. The curtains close and cover them.)

Gas. (From behind curtain.) For my wife! (Shriek heard from the Marquis.) For my murdered child! (p. 15)

In fact, two vehicular homicides are reported, the first "a day and a half's journey out of Paris" (p. 6) narrated in I, i, by the Mender of Roads, the victim is not a child but an adult cripple working on the road — and the perpetrator of the crime is not the coachman, but the Marquis himself, who is described as "striking with a heavy whip whenever any of the poor attempted to approach the carriage. . . ." The second is represented by "A crash heard, followed by a shriek" (p. 6) off-stage, followed by Gaspard's rushing into the Defarges' wineshop to announce, "My child is slaughtered!" prior to the entrance of the Marquis himself in I, i. Afterward, the Marquis sits down with Barsad to share a glass of wine and receive the latest intelligence from England regarding his nephew's trial for treason. Thus, Fox Cooper avoids having to show either the carriage accident or the trial on stage.

The dramatist, indulging in the practice of such contemporaries adaptors as Dion Boucicault in The Streets of London (1864), then exploits the nineteenth-century theatre's capacity for spectacular pyrotechnic effects in a scene worthy of the latest action movie. The Marquis' servants rush on after their master's chateau (in the play, transformed into a townhouse) begins to dissolve in a "general conflagration — the entire back of scene falls, discovering the Marquis on couch, with Gaspard's knife in his breast, and a circle of paper round it." Just as Gabelle reads the note aloud, the Revolution breaks out in earnest: "The smoke clears away, discovering the street beyond, crowded with people who exclaim loudly, Extermination!" Thus, Cooper effectively combines distinct events of Dickens's Book the Second: the description of the storming of the Bastille in Ch. 21, the death of Foulon in Ch. 22, and the earlier assassination of the Marquis St. Evremonde (Ch. 9).

For veteran stage-adapter Fox Cooper it was not enough that the curtain drop on virtue triumphant — the hero had to be saved, no matter how improbable his rescue, no matter how the happy ending for Sidney Carton violated the intention of the original novel. The picture on the title-page, of a rather young Miss Pross grabbing Jacobin-capped, wild-haired beauty Madame Defarge, directs the reader to the play's sensational climax on page 22, emphasizing the confrontation of good and evil, and demonstrating how the former, though unarmed, is proof against the latter, even when the villainess wields a pistol. The plate implies a commercial exploitation of the female form rather than the Dickensian valorizing of British over French values, although the dialogue is certainly faithful to Dickens's text. Melodramatically, the young Frenchwoman exclaims, "No answer — this silence. Ah! I have sudden misgiving that they are gone." The personification of virtue responds, " I am stronger than you, I bless heaven for it — I'll hold you till one or the other of us faints or dies."

The succeeding "Tableau," possibly intended to underscore the significance of the moment, depicts the reactions of Doctor Manette, Darnay, Lorry, and Lucy to the evil Therese's defeat; the fatally wounded fanatic then indulges in an impassioned and delusional death-speech:

What a dreadful pang! I gasp for breath. Yet it was but fancy — and 'tis past — it is past. I must be quick, or Evremonde will be dispatched. They are calling me. But is this real? Yes, yes! I see the guillotine with a thousand faces gazing upwards at the condemned, as from a sea of dark and troubled water. The Ministers are robed and ready. Crash! A head is held up! 'Tis Evremonde's. I hear them calling, "Therese, you are too late!" (She starts up, and falls back again in a moment, exhausted.)

Then, noticing that Darnay is present, she cries, "Ah! Do my eyes deceive me?" to which her moral antithesis, Lucy, waxing biblical, ripostes: "Yes, woman! Alive, and safe! To smite thee in thy guilt." Therese, "rising with difficulty," attempts in vain to grab Darnay, then falls dead.

Thus, Cooper fulfils the primary expectation of melodrama: the ultimate defeat of evil. The second expectation of this sensational genre, the triumph of the virtuous hero, Cooper fulfills by cheating the repressive regime of Carton, who appears moments after "The noise of the guillotine descending is heard, and with suppressed cries. — Darnay shrieks aloud, and starts with frantic energy." However, in the nick of time Darnay is prevented from returning to redeem Carton's life with his own by his "friend" (although the novel hardly characterises their relationship as one of unadulterated friendship) Carton himself, dressed in Barsad's clothes:

All stand transfixed in wonder. Darnay throws his hands back, as if in search of support, his head thrust forward, regarding Carton with wild but joyous terror.

Dar. The victim, then, was —

Car. The traitor, Barsad!

Dar. Joy! Joy! My friend yet lives, and is restored to us! Thank heaven! Thank heaven!

(Music. — The characters kneel in thankfulness to Providence, except Carton, who forms the centre of the tableau, as the curtain falls)

The closing musical accompaniment reminds us that the addition of music to a dramatic script earlier in the century had been the British playwright's way of escaping the strictures of The Theatres Act of 1737, which vested the privilege of staging "legitimate" drama in the London houses of Covent Garden and Drury Lane. "It was mainly the use of music, first to separate the various incidents and later to underline them, that gave its name to this popular type of play" (Hartnoll 347). Other features of the Cooper text that identify it as a melodrama include the comic man (Jerry Cruncher) and comic woman (Miss Pross), the aristocratic villain (the Marquis de St. Evremonde, who, thwarted in his evil designs, cries, "Confusion!"), the lower-class villain (Madame Defarge), the good old man (both Lorry and Dr. Manette), heightened emotion (evident in the scenes cited above), and the continuous conflict between unalloyed good and evil (which begins with Dr. Manette and the brothers St. Evremonde, and ends with Miss Pross and Therese Defarge).

Writing in 1987, Philip Bolton enumerated 136 adaptations of Dickens's novel for (as opposed to 357 of A Christmas Carol and 407 for Oliver Twist by the same date). Ten years later, Paul Davis noted the "joint English-French television production made in 1989 for the anniversary of the Revolution" (381) — and the number of stage has undoubtedly increased since then. But those first adaptations of the 1860s stand out for their authors' having transformed Dickens's subtly narrated tragedy into straight-forward melodrama complete with a happy ending. Perhaps these early adapters felt that their primarily working-class audiences would not have actually read the novel, and would therefore be better pleased by a play that recalled Sidney Carton to life, even if such a conclusion so obviously violated Dickens's narrative intention.

Although the theatrical life of A Tale of Two Cities began over twenty years after the earliest Pickwick took to the stage, Bolton lists forty nineteenth-century adaptations for the former and 76 for the latter; another hundred stage and film versions of Dickens's revolutionary tale have appeared since 1901, there having been a flurry of activity around the bicentenary of the French Revolution. However, Oliver Twist, the Carol, Nicholas Nickleby, and Pickwick Papers remain in the lead, with totals (as of 1987) of 407, 357, 257, and 212 stage, film, and television adaptations respectively.

Related Material

- A Transcription of Fox Cooper's July 1860 Dramatic Adaptation of Charles Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities

- Films and Plays from A Tale of Two Cities (1899-1980)

- Dramatic Adaptations of Dickens's Novels (1836-1870)

Image scan by the author [You may use the image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Bolton, H. Philip. Dickens Dramatized. Boston: G. K. Hall, 1987.

Booth, Michael. English Plays of the Nineteenth Century. Oxford: Clarendon, 1969. Vol. 1.

Colby, Robert A. "Thackeray and Dickens on the Boards." Dramatic Dickens, ed. Carol Hanbery MacKay. Basingstoke and London: Macmillan, 1989. Pp. 139-151.

Cooper, Fox. The Tale of Two Cities; or, The Incarcerated Victim of The Bastille. An Historical Drama, in a Prologue and Four Acts. London: John Dicks, 1860. Dicks' Standard Plays, No. 780.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts on File, 1998.

Hartnoll, Phyllis, ed. The Concise Oxford Companion to the Theatre. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1972.

Leech, Clifford, and T. W. Craik, eds. The Revels History of Drama in English, Vol. VI: 1750-1880. London: Methuen, 1975.

MacKay, Carol Hanbery. "'Before the Curtain': Entrances to the Dickens Theatre." Dramatic Dickens, ed. Carol Hanbery MacKay. Basingstoke and London: Macmillan, 1989. Pp. 1-10.

Morley, Malcolm. "The Stage Story of A Tale of Two Cities." Dickensian 51 (1954): 34-40.

Created December 7, 2002

Last modified 19 January 2026