This review has been transcribed, linked and illustrated for the Victorian Web by Philip V. Allingham, who also discusses separately the illustrations for the volume, by both Luke Fildes (for the original chapters) and Zoffany Oldfield (for the new version). Page numbers in the review are given in the text in square brackets. Full details of the review are given in the bibliography.

dwin Drood solutions have become to me a weariness to the flesh, and I confess that I should like a long respite from them. Scarcely a month has passed during the last seven years or so but I have been invited to join in Drood controversies, to read new Drood books, to pass opinion upon original solutions of the Drood problem, to examine piles of unpublished Drood manuscripts, to read through long Drood papers which have been delivered before literary societies, to analyse other people’s opinions on Drood, and in short to immerse myself in a flood of Drood literature to the exclusion of all other objects and interests on this planet. If I were a man of abundant means and unlimited leisure (which I am not) it seems that I could devote the main part of my life to an Edwin Drood controversy. I frankly acknowledge this is my own fault. I ought never to have started those “Clues” which, in a wild moment in the year 1907, exercised their fascinating lure upon me. At the time I was innocent enough, having no prophetic foreknowledge of the risk that I was personally running or of the tumult that would rage in the Dickensian world. It was, in fact, an accident — for I must not compliment myself by using the term of favouring friends and call it an "inspiration" — but I realise now that it was an awful mistake for which I must pay a deserved penalty.

Title-page of the book under review.

Such then is my mood. The very mention of the name of Edwin Drood has of late years made my heart palpitate with a vague dread, and the sight of a Drood manuscript upon my desk effectually destroys my appetite for the remainder of the day. It might be thought, under such circumstances, that the receipt of a volume of no fewer than 528 pages would almost have a tragical result. On opening, a little tremulously, the volume, “The Mystery of Edwin Drood; completed in 1914, by W.E.C.,” I was somewhat appeased to find that exactly half the number of pages were those of Dickens himself, and so far held no new terror forme. The other half is by a modest and unknown author who conceals his identity under initials.

This very modesty served to disarm me, for I remembered the absolutely blatant manner in which two or three of the former authors of “Continuations” had announced themselves to the public, and endeavoured to secure unmerited fame by linking their names with that of Charles Dickens. There was a further inducement for me to read the new volume, and that lay in the attractive manner of its printing by Mr. J. M. Ouseley, and the clever illustrations, deserving of special commendation, by Zoffany Oldfield.

Beginning on page 284 I soon discovered that there were points in the new text which would be well worthy of serious consideration. I do not say for a moment that the giant’s robe fits W.E.C. to a nicety, but I feel I can honestly declare that he does not disgrace it. He has [238/239] something of the Dickens style, something of the elusive Dickens quality, something even of Dickens’s almost inimitable humour. And although it is not “the real thing” I feel that it is good imitation.

But a continuation of “The Mystery of Edwin Drood”, in order to be justified at all, must not only appeal to us as literature. It must present a solution of the problem, or perhaps it would be better to say a series of solutions of the different parts of the complex problem, the mechanism of which was only half-disclosed. It needs indeed a clever man to offer to perform the whole task, and to attempt it in the Dickens fashion, and surely boldness was never exceeded in the case of W.E.C., who, so far from pondering upon the puzzle for years, as most of us have done, “only read the published portion of the story quite lately for the first time,” and forthwith rushed to the elucidation. He must therefore have acted intuitively, and not have proceeded by patient argument and analysis. In fact, after reading his preface, we can almost hear him shout “Eureka!”

I had thought that with the publication of Sir W. R. Nicoll’s volume the possibilities of Edwin Drood solutions had been practically exhausted; and I had even believed that the “Trial of John Jasper” last January would serve as a solemn warning to all of us not to tempt the fates any more. Yet, as I continued to read the pages of W.E.C., my flagging spirits once more fluttered, and I felt a new excitement as he approached his dénouement. All this of course is not saying that I agree with him. Without giving away his secret I must state that I disagree most emphatically with a number of the details, more particularly with those concerning the possible fate of Mr. Sapsea, the boy Deputy, and Neville Landless. But certain essential parts of the plot are not essential parts of the “mystery,” and therefore it is necessary to concentrate upon the main theme of Jasper and Drood.

"Jasper enquires for Durdles," by Zoffany Oldfield.

There are, of course, two questions to be definitely resolved. Was Drood murdered, and did Jasper murder him; or was Drood attacked by Jasper and did he escape? W.E.C. believes the crime was actually committed, and that Jasper was the culprit. So far I am with him. He believes that the character called Mr. Datchery was brought upon the scene in order to convict the criminal. Here I am with him again. But, in my opinion, he spoils the whole dramatic nature of this intervention by declaring that Mr. Datchery was not in disguise, that he had no direct interest in the tragedy, and that he had no higher motive for his action than a vague desire to distinguish himself by amateur detective work. This is decidedly weak; I might almost say fatuous. Such a Datchery can be eliminated, but there are still two characters left to play a great part, and to make this continuation of “Edwin Drood” worth the writing. Those two are Helena Landless and Jasper himself.

W.E.C. invests Helena Landless with almost superhuman power; at all events he takes us to the verge of the supernatural. Hypnotism was not recognised in the time of Dickens [see appended note] and W.E.C. is guilty of an anachronism in introducing it into his narrative. All the same, he utilises it with power and subtlety. The chapter containing Jasper's [239/240] confession is almost uncanny in its intensity, and the vision of Helena holding his hand and listening while the incriminating words are drawn irresistibly from the lips of the unconscious man is one that haunts the imagination. "With closed eyes, her hands still grasping Jasper’s, amid the silence of that wretched opium den in a London slum, Helena saw the resurrection of a dastardly crime which no living eye but that of the Choirmaster had ever seen.” The description which follows reads almost like a page torn from a volume on black magic.

But this reconstitution of the scene, though it might satisfy the psychologist, would not be good enough for a court of law, and W.E.C. probably understood that when he carried his plot a stage further and provided us with another thrilling surprise. That surprise is gruesome enough. When Jasper murdered Edwin Drood and cast him in the vault and covered him with quicklime, it did not occur to him that the quicklime might have lost its potency, and that consequently its destroying agency was impaired. Even Eugene Aram could not have undergone a greater shock when the signs of crime, supposed long to have disappeared, once more confronted the criminal’s eyes. “If,” argued Jasper, “the body is consumed, there can be neither danger nor trial. Neville Landless now goes free, because there was no dead body to prove a murder had been committed, therefore even my morbid brain must admit that if there is no body found in the vault there can be no evidence that one was ever put there by me. If there is no body? But is it consumed? That at all events is a fact I can ascertain. But if it is not all consumed?” (At this thought the man shuddered with innate horror). “My God! in such case where shall I hide the evidence of this horrid curse I have fastened round my soul.” The remote chance turned out to be correct. The one miscalculation in a remarkably calculated crime was to prove Jasper’s undoing. Let the conclusion be stated in the author’s own words:—

“He thrust the lantern into the dark void, and as he learned the awful truth the filmy look which had so often afflicted his sight again came over his eyes for a few seconds. For there, conjured up by his heated imagination, the figure of Edwin Drood rose up from his grave and stood before him — a shadow of silent terror to the distraught mind of the quaking murderer.

“This apparition of Jasper’s now thoroughly ill-balanced brain, being merely the sub-conscious mental picture of his own recollection of his nephew when last he had seen him alive, passed almost as quickly as it had appeared. As it vanished the belfry clock chimed two quarters after midnight.

Drawing the back of his gloved hand across his eyes, as though to clear away some mist that obscured his sight, his lips twisting and moving like those of an idiot, and a trembling moan of unbearable mental suffering issuing from between his chattering teeth, the wretched man picked up the empty lime-sack, climbed over the broken masonry and proceeded to lift the mummy-like remains of what had once been Edwin Drood.

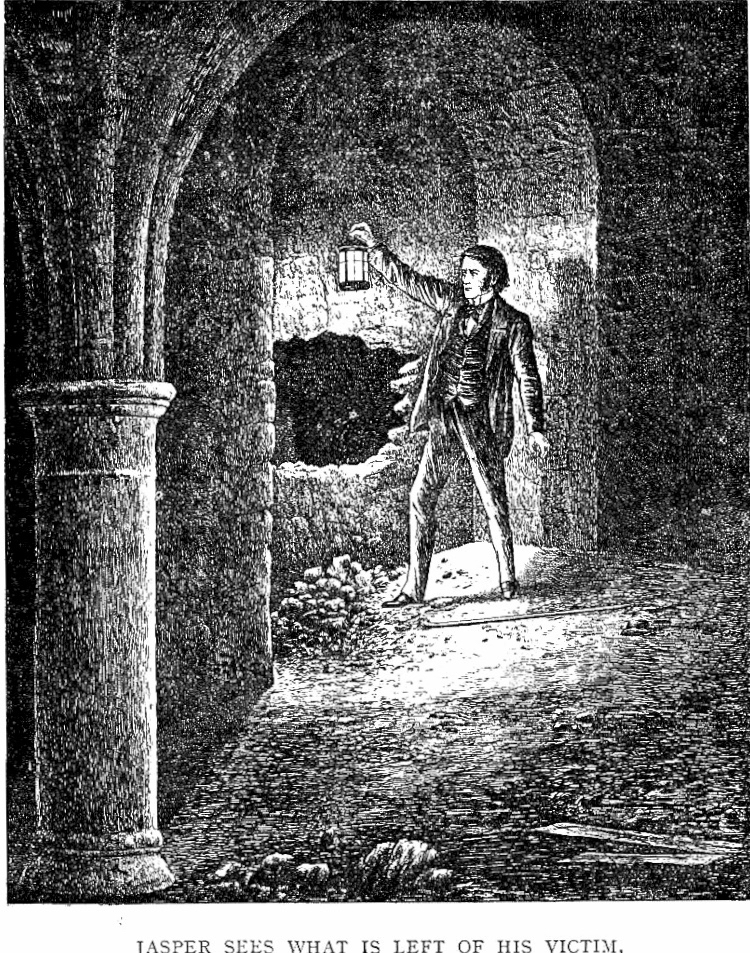

"Jasper Sees What Is Left of His Victim," by Zoffany Oldfield.

“Whatever the psychological explanation” may be of Jasper’s vision, [240/241] that is, the apparition of the head, shoulders and part of the body of his nephew — must be left to those who are learned in spiritualistic lore. This history can concern itself only with the fact that, owing to the loss of its full strength by long exposure, the lime used by Jasper to destroy the body of his victim had succeeded only in consuming the extremities and a portion of the lower part of the body; then, having exhausted its destructive power, the preservative action of slacked lime coming into force, it had mummified the remainder. The sight, therefore, that "appeared before the Choir-master’s horrified vision was the distorted and somewhat shrunken remains of the upper portion of his nephew’s body, the black silk scarf still loosely covering his victim’s face.”

What, then, should be our final judgment on “W.E.C.’s” volume 2? It is more than a curiosity, more than a tour de force, more than an ingenious piece of guess-work. As literary workmanship it stands higher, in my opinion, than any other of the Drood continuations. It is novel, it is suggestive, and it provides a series of well-kept secrets. The author avoids triviality and folly, though he is not altogether guiltless of “gush.” But does W.E.C. solve the crucial problem? Does he even satisfy us that his solution is probable and reasonable? I am a prejudiced person, but, trying hard to free myself from bias I am bound to answer No. The mighty mind that conceived the puzzle still holds the secret.

Mesmerism: A Note

The reference to hypnotism was not in fact anachronistic. W.M. Jacob explains:

From 1838 Dr John Elliotson, credited with inventing the stethoscope, professor of the principles and practice of medicine at University College, one of the first medical-training institutions, and senior physician to University College Hospital, with a large private practice, a pioneer in medical professionalism, and founder of the London Phrenological Society, began giving immensely popular public demonstrations of mesmerism at University College Hospital. He believed he had stumbled on a great discovery of medical science. Although he alienated the conservative medical establishment and was discredited over accusations of deliberate trickery, and forbidden to practise mesmerism in the hospital, mesmerism became significant in elite scientific circles. [183-84]

Dickens's friendship with Elliotson and his own interest in the subject have long been recognised, and are fully discussed in Fred Kaplan's Dickens and Mesmerism: The Hidden Springs of Fiction (1975).

Related Material

- Illustrations by Sir Samuel Luke Fildes for The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870)

- Unravelling The Collins-Fildes Monthly Wrapper for The Mystery of Edwin Drood: The Solution to Dickens's Conundrum?

- Some Early Dramatic Solutions to Dickens's Unfinished Mystery

- A Gallery of Sir Luke Fildes’ Illustrations for Edwin Drood (1870)

- A Gallery of Zoffany Oldfield’s illustrations for Edwin Drood (1914)

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles, and W. E. C. [William Edward Crisp]. The Mystery of Edwin Drood, ed. Mary L. C. Grant. New text drawings by Zoffany Oldfield. London: J. M. Ouseley, 9 John Street, Adelphi, 1914.

Dickens, Charles. The Mystery of Edwin Drood. With Illustrations [by Sir Luke Fildes, R. A.] London: Chapman and Hall Limited, 1870.

_______. The Mystery of Edwin Drood; Reprinted Pieces and Other Stories. With Thirty Illustrations by L. Fildes, E. G. Dalziel, and F. Barnard. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1879. Vol. XX.

Fildes, L. V. Luke Fildes, R. A., A Victorian Painter. London: Michael Joseph, 1968.

Forster, John. The Life of Charles Dickens. In two volumes — with illustrations. The Charles Dickens Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1870. Vol. II (1847-70).

Jacob, W.M. Religious Vitality in Victorian London. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021.

Kaplan, Fred. Dickens and Mesmerism: The Hidden Springs of Fiction. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1975.

Kitton, Frederic G. Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, "Phiz," Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Landseer, Palmer, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. Amsterdam: S. Emmering, 1972. Re-print of the London 1899 edition.

Paroissien, David (ed.). "The Illustrations," Appendix 3 in Charles Dickens's The Mystery of Edwin Drood. London: Penguin, 2002, pp. 294-299.

Walters, J. Cuming. "Edwin Drood Continued." Dickensian Vol. 10, No. 9 (September 1914): 238-241. Internet Archive. Web. 28 August 2025.

Created 28 August 2025