"However late in the evening I may arrive at a place, I never go to bed without my impression." Henry James, A Little Tour of France 96

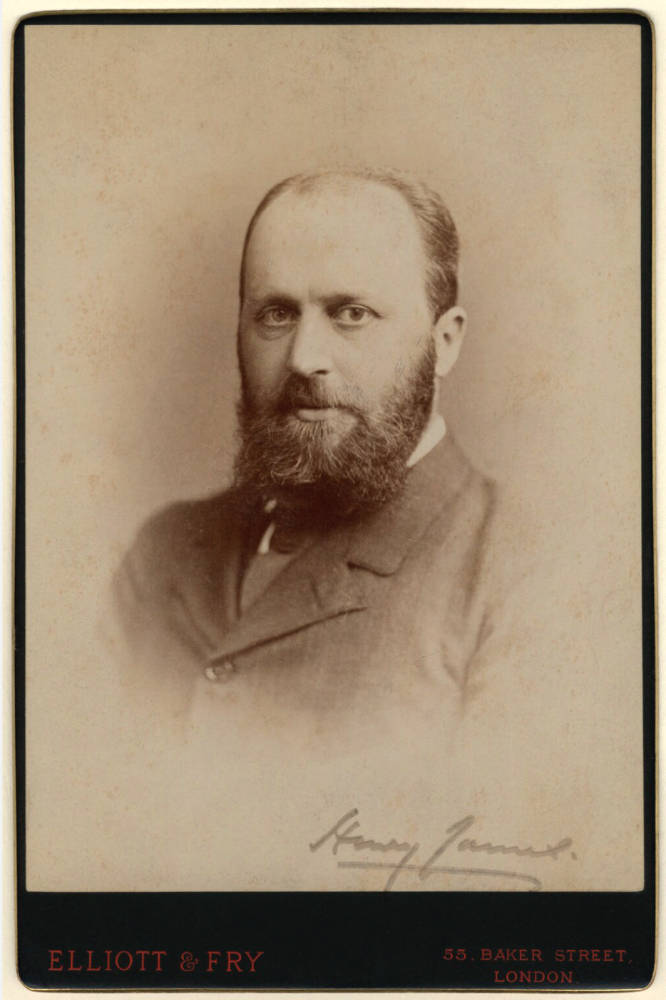

Henry James. November 1884 Elliot & Fry. Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery London.

Henry James arrived by steam locomotive, on the "noiseless little railway running through the valley" (Portraits 239), at Much Wenlock station, on Thursday, 12 July 1877. The Welsh slate, gabled, station master's house, designed by the local railway engineer Joseph Fogerty and built in 1864 when the passenger station opened, was already partly covered with ivy and climbing plants. Beneath the finial of the central gable was the insignia of the private Wenlock and Severn Junction Railway company, a "Wen and Lock". The platform was decorated with pots of shrubs and summer flowers in bloom. In front of a white fence, a board with the name, Much Wenlock, blazoned in large letters, welcomed the traveller. The porter unloaded James's trunk from the luggage-van and placed it in the great square two-horse barouche, an old-fashioned, high-hung vehicle, with a green body and a faded hammer-cloth, waiting for him in front of the station (Cf.Princess Casamassima 315). How different this was from young James's first coach journey from Liverpool to London in 1855.

James cut a dashing figure with his long, silky, black beard, receding hairline, smooth forehead and penetrating eyes, not unlike an Elizabethan sea captain (West 46-47). He was certainly most attractive. This was confirmed by the famous actress Fanny Kemble who described her guest that Christmas, at Alveston Manor House, near Stratford-upon-Avon, as "our dark-bearded, handsome American friend" (Life 215).. Crawley, Gaskell's Yorkshire coachman, proudly drove the foreign guest down Station Road, turned left into Sheinton Street, past the Almshouses (Spring in a Shropshire Abbey 20). Just before reaching Holy Trinity Church with its lofty steeple, the coachman took a sharp left turn into the Bull Ring, past a tower, before turning right through the open gates into the main drive leading to the Prior's Lodging, the residential part of Wenlock Abbey.

*

James was always at home in the world of the landed gentry and aristocracy. His host's pedigree and coat of arms were in Burke's Landed Gentry, while his hostess's could be found in Burke's Peerage. Gaskell had inherited two large estates, Thornes House, near Wakefield, Yorkshire, and Wenlock Abbey, on the death of his father on 5 February 1873. He was now landowner of much of the town and parish of Much Wenlock.

Henry James enjoyed the generous hospitality of the Gaskells. "I certainly like them" he wrote, adding that he found his host "an excellent fellow, an entertaining companion & the pearl of hosts" (Monteiro 41). The feeling was mutual. Gaskell had expressed his liking for James in a letter to Adams, who commented in his reply of 22 August 1877: "I am glad you liked Harry James, and am glad you had him to Wenlock" (44n2).

The mid-summer bad weather contributed to the bonding, enabled them to get to know each other for they "talked together as people talk in an English country-house when, during the three days of a visit, two, alas, turn out too brutally pluvial. This is a rather big thorn on the Wenlock rose, which, however, on my first day, bloomed irreproachably" (41; cf Life 2.126). How very grateful James was to receive the invitation: "It was therefore all the more meritorious in them to invite me hither, where they have come only for a week, to interrupt London & be alone." (41).

Gaskell's young bride, whom he had married on 7 December 1876, was Lady Catherine Henrietta Wallop; she was the daughter of the 5th Earl of Portsmouth, of Hurstbourne Park, Whitchurch, Hampshire, a descendant of the great scientist Sir Isaac Newton. At the time of James's visit, Lady Catherine was only twenty years old and was six months' pregnant with her first child, a son Evelyn, to be born on 19 October 1877. A second child, a daughter Mary, was born in 1881. It was not until late February 1877 that Gaskell brought his bride to Much Wenlock where she was warmly welcomed as the Lady of the Manor and celebrations took place in the town throughout the day.

As the date of Lady Catherine’s confinement approached, very few visitors were entertained at Wenlock Abbey. James was the only one privileged to stay during that summer (12-16 July) and his signature was the last in the Visitors’ Book of 1877. He was enchanted by Lady Catherine's youth, charm and her Englishness, and, he dared to admit, was a little in love with her. He sent Adams this beautiful description of her:

A rose without a thorn, moreover, is Lady Catherine G., of whom you asked for a description. I can't give you a trustworthy one, for I really think I am in love with her. She is a singularly charming creature – a perfect English beauty of the finest type. She is, as I suppose you know, very young, girlish, childish: she strikes me as having taken a long step straight from the governess-world into a particularly luxurious form of matrimony. She is very tall, rather awkward & not well made, wonderfully fresh & fair, expensively & picturesquely ill-dressed, charmingly mannered &, I should say, intensely in love with her husband. She would not in the least strike you at first as a beauty (save for complexion:) but presently you would agree with me that her face is a remarkable example of the classic English sweetness & tenderness – the thing that Shakespeare, Gainsborough &c, may have meant to indicate. And this not at all stupidly – on the contrary, with a great deal of vivacity, spontaneity & cleverness. She says very good things, smiles adorably & appeals to her husband with beautiful inveteracy & naturalness. There is something very charming in seeing a woman in her "position" so perfectly fresh & girlish. She will doubtless, some day, become more of a British matron or of a fine lady; but I suspect she will never lose (not after 20 London seasons) a certain bloom of shyness & softness.– But I am drawing not only a full-length, but a colossal, portrait. –" [41-42]

James is a model of discretion about her pregnancy: the reference to her as "a woman in her 'position'" being a veiled allusion to her physical state. Lady Catherine was a sensitive, caring person with a keen interest in gardening, history, literature and the arts. She kept records of conversations and made copious notes, many of which are incorporated into Spring in a Shropshire Abbey (1905), chronicling a cycle of her life between January and July at Wenlock Abbey with her daughter Bess (Mary), her staff (gardener, gamekeeper, butler, cook, housekeeper), friends and local characters. She enjoyed some fame as a writer, especially about Shropshire life. Over the years she welcomed to her home the novelist Thomas Hardy (1840-1928; Wenlock Abbey 215-28), the explorer Henry Morton Stanley and many other eminent people (245-57). She was skilled with a bodkin and, with a team of helpers, including her friend Constance who lived nearby in the Red House, produced a colourful embroidery, a "huge text worked in wool" depicting four angels praising God. It was based on Burne-Jones's Angeli Laudantes, a design that was used for stained-glass windows and tapestries.

Angeli Laudantes by Lady Catherine Milnes Gaskell.

Tame and wild animals – two kittens, a dog, a lion and a tiger – scamper among the foliage at the feet of the angels, against a background of red roses, lilies and greenery. The tableau is framed by a border of oak leaves and oak apples. This embroidery now hangs in Holy Trinity Church, Much Wenlock.

Lady Catherine Henrietta Milnes Gaskell in later years. 28 November 1927. Courtesy National Portrait Gallery London. Given by Pinewood Studios via Victoria and Albert Museum, 1989. Click on image to enlarge it. NPG x184746t

Sometimes Lady Catherine worked alone and on one occasion she referred to her work on a particular motif of a blue dragon: ‘Ten minutes later, and I was seated before my embroidery. Today I had a blue dragon to work. I tried to see and to reproduce in my mind's eye Burne Jones' wonderful tints of blue with brown shades and silver lights, and so the hours passed’ (Spring in a Shropshire Abbey 176).

Lady Catherine described more fully the embroidery on her curtains:

The background is of yellow linen and is thickly covered with fourteenth and fifteenth century birds, beasts, and flowers, and in the centre of each there is an angel.

Each curtain is three yards four inches, by two yards four inches. The birds, beasts, and flowers are all finely shaded and are worked in crewels, tapestry wools divided, in darning and fine Berlin wools, and all these various sorts seem to harmonize and mingle wonderfully well together.

The picture, for it really is a picture, was drawn for me by a very skilful draughtsman. The birds, beasts, and angels have been taken from old Italian work, from mediaeval stained-glass windows, and from old missals, and then drawn out to scale. There are tender roses, Italian carnations, sprays of shadowy love-in-the-mist, dusky wallflowers, and delightful half-heraldic birds and beasts, running up and hanging down the stems. It is a great work. [Spring in a Shropshire Abbey 13-14]

These embroidered curtains were created for the private, medieval oratory in her Abbey (Wenlock Abbey, 266-71).

James would have nurtured her interest in the Arts and Crafts with first-hand accounts of his meetings with Morris and his circle, and descriptions of Burne-Jones's paintings. He may also have shared his impressions of the Turners he had seen at the Ruskin family home at Denmark Hill on his visit in 1869. Perhaps memories of these were revived by the sight of "two Turners" hanging on the panelled wall of the chapel hall in Wenlock Abbey? (Spring in a Shropshire Abbey 74) One of Turner's wealthy patrons was Sir Watkin Williams Wynn II (1749-1789): Lady Catherine's husband was a descendent of the Williams Wynn family and would most likely have inherited the two Turner paintings.

Lady Catherine died in 1935 and is buried in the churchyard of Holy Trinity Church, Much Wenlock, in the shadow of her beloved Shropshire home.

*

James lived for five days at Wenlock Abbey – he was the sole guest of Gaskell and Lady Catherine, not part of a large house party – in a state of heightened awareness and creativity, conscious of every detail and nuance, observing, recording and accumulating a wealth of impressions. "Henry James Jr" signed the Visitors' Book (which is now in a private collection) on 14 July 1877. He was a sophisticated, sensitive guest, and in his writings about his stay he mingled "discretion with enthusiasm" (Portraits 232), not wishing to violate the hospitality, the "act of private courtesy" (233) afforded him by his host. This was his very first experience of living in an inhabited, authentic medieval abbey, far removed from William Morris's contrived "medieval mise-en-scène of Queen Square" (Autobiography 515). It was the essence of what was lacking in America and exactly what James craved. Nathaniel Hawthorne, in his preface to his novel Transformation, had recognised the "difficulty of writing a romance about a country where there is no shadow, no antiquity, no mystery, no picturesque" (James, Hawthorne 42). James listed at length and with greater emphasis things that were "absent from the texture of American life" and, to a degree, obstacles to his creativity:

No sovereign, no court, no personal loyalty, no aristocracy, no church, no clergy, no army, no diplomatic service, no country gentlemen, no palaces, no castles, nor manors, nor old country-houses, nor parsonages, nor thatched cottages nor ivied ruins; no great Universities nor public schools – no Oxford, nor Eton, nor Harrow; no literature, no novels, no museums, no pictures, no political society, no sporting class – no Epsom nor Ascot! [43]

Gaskell epitomised so much that James admired and sought: educated at Eton, and Trinity College Cambridge, of a prestigious and ancient lineage, inhabiting a medieval abbey.

James steeped himself in the atmosphere and recreated the working abbey, priory and church of the Middle Ages; life before the vandalism and dissolution of the monasteries in the sixteenth century, an iconoclastic act that art critic Waldemar Januszczak has described as "a cultural tsunami that eradicated a millennium's worth of British artistic achievement" (7). How ironic that Gaskell's alma mater, Trinity College Cambridge, was founded by the same powerful man (King Henry VIII) who expelled the monks from Wenlock Abbey. James's abbey is soon peopled with ghosts of the monks, friars and abbots, carrying on with their centuries-old rituals in silence and in obedience to the rules of their order. Some came from Burgundy in 1080, from the priory at La Charité-sur-Loire, a daughter house of the great Cluny Abbey.

Chapter House, Wenlock Abbey, by Whymper.

Among the ruined Priory church and other remains, James attempts to recreate the vast edifice and restore it to its original grandeur: "Adjoining the house is a beautiful ruin, part of the walls and windows and bases of the piers of the magnificent church administered by the predecessor of your host, the abbot. These relics are very desultory, but they are still abundant, and they testify to the great scale and the stately beauty of the abbey" (Portraits 238-39) As James lies on the grass near the stumps of the four central pillars that supported the tower, he is well placed to grasp the huge girth – approximately twelve yards – of these diamond-shaped columns, some four yards in diameter: ‘You may lie upon the grass at the base of an ivied fragment, measure the girth of the great stumps of the central columns, half smothered in soft creepers, and think how strange it is that in this quiet hollow, in the midst of lonely hills, so exquisite and elaborate a work of art should have arisen’ (239).

The ruins that were visible were in a state of considerable decay. They were the Romantic subject matter of picturesque paintings by artists such as Paul Sandby Munn (1773-1845), Paul Sandby (1730/31-1809), the Rev. Edward Pryce Owen (1788-1863) and John Sell Cotman (1782-1842). Cotman and Munn travelled together in the summer of 1802, leaving London in early July, reaching Bridgnorth on 8 July and then Much Wenlock where both drew the Priory; they continued to Broseley, Ironbridge and Coalbrookdale (see Kitson, 41-42). Horses, cattle and sheep were often depicted grazing among the ruins. As the roofs collapsed and the walls fell down and crumbled, local people collected the rubble in barrow loads for building cottages, sheds, outhouses and roads. In Spring in a Shropshire Abbey, Lady Catherine Milnes Gaskell documents the vivid memories of local people who used the Priory and Abbey ruins as a quarry and took whatever stone they needed. One of the worst offenders appears to have been '"King Collins', as the old people used to call Sir Watkin's agent, who lived in the red-brick house which is now the vicarage, [who] carted away whatever he had a mind to" (Spring in a Shropshire Abbey 224). The vandalism of Sir Watkin Williams Wynn's trusted employee – W.W. Wynn was then the owner of the Priory and Abbey estate – seems to have been widely known and this shocking state of affairs is confirmed in Murray's 1870 Handbook: "A large portion of the abbey was pulled down many years ago by a Vandal in the shape of a house agent, but further ruin was stopped by the then Sir W. W. Wynn" (41).

Left: The Lavabo at Wenlock Priory. . Right: Blind arcade on the north wall of the Chapter House, Wenlock Priory. Photographs 2004 and 2014 by the author. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

At the time of James's visit, many of the ruins were hidden deep beneath long grass and briar. He did not know that he was sitting near a grassy mound that concealed part of a rare feature – the great free-standing lavabo or lavatorium. It was strategically situated in the south west corner of the cloister, near the entrance to the refectory, for the monks' cursory ablutions after their heavy and dirty manual work in the fields, forests and gardens, before they ate in the communal room or went into the church. The existence of the lavabo may have been unknown to Gaskell and his family: it is not mentioned in Murray's first Handbook for Shropshire of 1870. In its heyday in the twelfth century, the covered, octagonal, open-arcaded building, three storeys high, supported by columns, could accommodate sixteen monks simultaneously washing their hands. Water from a nearby well was piped into a large, round basin in the centre of the lavabo, and like an elaborate fountain gushed through the mouths of sixteen carved heads into the circular trough below. The gargoyles or spout heads were embedded in the lower part of highly decorative sculpted designs. The base of this trough was faced with carved slabs, cut to the curve, approximately two and a half feet high. The entire construction was of local limestone. It must have been a magnificent and awe-inspiring monument until much of it was destroyed after the dissolution of the Priory in 1540. However, the inner part partially survived, protected through the centuries by the covering of mother earth, and was not unearthed until after James's first visit.

In keeping with the aesthetics of the construction, the panels around the base were probably all carved with religious scenes, although only two of these survive. On 16 October 1882, Gaskell sent Adams photographs of some saints he had discovered. Adams replied, on 3 December 1882:

My dear Carlo, Your letter of Oct. 16 has been lying some weeks on my table, and the photographs of your discovered saints have adorned my library. They are interesting, and if you find out when they were done, I would like to know. [Samuels 121]

This may be a reference to the two existing panels. One of the sculptured stone panels around the base represents two contemplative saints, standing in coupled arches. The beardless saint on the left is supporting his chin and cheek with his left hand whereas the stocky, bushy-bearded figure on the right – possibly St John the Evangelist or St Paul whose usual attributes are a book – is pressing a heavy tome, the Word of God, to his chest. Another panel depicts two rowing boats, one above each other, framed beneath a trefoiled arch. There is an oarsman and a male passenger in each. In the upper boat, the passenger appears to be sleepy; his head is drooping and his raised hand gesture implies a rejection of some kind. The lower boat is clearly half immersed in turbulent water, and the right hand of the bearded passenger (possibly one of the disciples) is gripped tightly by a Christ-like figure standing on water (John 6). The symbolism of water would have been most appropriate for the lavabo.

As soon as James crosses the threshold of his host's abode, "through an old Norman portal, massively arched and quaintly sculptured, [...] the ghosts of monks and the shadows of abbots pass noiselessly to and fro". "This aperture admits you to a beautiful ambulatory of the thirteenth century – a long stone gallery or cloister, repeated in two stories, with the interstices of its traceries now glazed, but with its long, low, narrow, charming vista still perfect and picturesque – with its flags worn away by monkish sandals, and with huge round-arched doorways opening from its inner side into great rooms roofed like cathedrals" (Portraits 238).

Two views of Wenlock Abbey in 1778, from engravings after Paul Sandby's drawings. In the left-hand one, the house is on the left; in the right-hand one, it is on the right. Source: Gaskell, Spring in a Shropshire Abbey, frontispiece, and facing p. 202.

These "great rooms" are "furnished with narrow windows, of almost defensive aspect, set in embrasures three feet deep, and ornamented with little grotesque mediaeval faces" (238). They are omnipresent and belong there: "to see one of the small monkish masks grinning at you while you dress and undress, or while you look up in the intervals of inspirations from your letter writing, is a mere detail in the entertainment of living in a ci-devant priory." In this ancient house, the remote past is all around and inescapable: so intense is the experience that "you feast upon the pictorial, you inhale the historic" (238). On arrival at Medley Park, Hyacinth Robinson (hero of The Princess Casamassima) experiences a not dissimilar reaction: "Round the admirable house he revolved repeatedly; catching every point and tone, feasting on its expression" (301). James's senses are heightened: his vision becomes acute, his sense of smell is laden with layers of the past, his historic consciousness flows.

The ancient building is imbued with mystery and life. Like an infusion, six hundred years of living history are transmitted, effortlessly yet with such force, so that even after only twenty-four hours he feels that he has lived in the place for six centuries. Here is "an accumulation of history and custom" that forms "a fund of suggestion for a novelist" that is indispensable (Hawthorne 43). He is part of the process of time and contributes to the wearing away of the fabric: "You seem yourself to have hollowed the flags with your tread," he reflects, "and to have polished the oak with your touch" (Portraits 240). This Jamesian motif is echoed, several decades later, in Marcel Proust's great novel À la recherche du temps perdu, translated by Charles K. Scott Moncrieff as Remembrance of Things Past. In the little church of Combray, the worshippers' actions of gentle touching contribute, slowly and almost imperceptibly, to the destructive force of time:

The old porch by which we went in, black, and full of holes as a cullender, was worn out of shape and deeply furrowed at the sides [...] just as if the gentle grazing touch of the cloaks of peasant-women going into the church, and of their fingers dipping into the water, had managed by agelong repetition to acquire a destructive force, to impress itself on the stone, to carve ruts in it like those made by cart-wheels upon stone gate-posts against which they are driven every day. Its memorial stones, bemeath which the noble dust of the Abbots of Combray, who were buried there, furnished the choir with a sort of spiritual pavement, were themselves no longer hard and lifeless matter, for time had softened and sweetened them, and had made them melt like honey and flow beyond their proper margins, either surging out in a milky, frothing wave, washing from its place a florid gothic capital, drowning the white violets of the marble floor; or else reabsorbed into their limits, contracting still further a crabbed Latin inscription, bringing a fresh touch of fantasy into the arrangement of its curtailed characters, closing together two letters of some work of which the rest were disproportionately scattered. [1.77-78]

As James strolls along the stone ambulatory on his way to the drawing-room, he is particularly aware of the passage of time, manifest in the crooked step and in the cracked lintels "worn by the myriad-fingered years". So acutely does he sense the continuity of life, that he dons, metaphorically, the mantle of a monk, and repeats their age-old rhythms, motions and gestures, even to the extent of casting a glance back down the cloister just before going through the round arched doorway at the end:

You walk along the little stone gallery where the monks used to pace, looking out of the gothic window-places at their beautiful church, and you pause at the big round, rugged doorway that admits you to what is now the drawing-room. The massive step by which you ascend to the threshold is a trifle crooked, as it should be; the lintels are cracked and worn by the myriad-fingered years. This strikes your casual glance. You look up and down the miniature cloister before you pass in; it seems wonderfully old and queer. [Portraits 240]

Past and present happily co-exist and even fuse. As he turns into "what is now the drawing-room", where he will find "modern conversation and late publications and the prospect of dinner", he is fully aware that the "new life and the old have melted together; there is no dividing-line" (240). In the drawing-room wall, an unusual detail attracts his attention: "a queer funnel-shaped hole, with a broad end inward, like a small casemate". James asked what it was, "but people have forgotten". His enquiries did not elicit satisfactory answers: "It is something of the monks; it is a mere detail" was the response. It was indeed "something of the monks" who had cut the funnel-shaped hole so that herbs and medicines could be dropped down through it to be picked up by the highly infectious and often severely disfigured lepers and untouchables, who were confined to a lazaret a few minutes' walk away in the woods at a place known as the Spittle. They were obliged to carry a bell to announce their arrival.

Occupying "a distinguished position in the drawing room" was a three-panelled, six-foot-high screen. Each panel was decorated with floral motifs: a large white lily with leaves on the left-hand panel, and smaller white flowers (different types of lilies) on the other two. This "handsomest appurtenance" was a wedding present from Henry and Clover Adams, and James reports that the screen had been a particular subject of conversation:

[Gaskell] furthermore calls my attention to the screen you sent him on his marriage & which occupies a distinguished position in the drawing room, & bids me say that he & his wife consider it their handsomest appurtenance. It is indeed very handsome & "reflects great credit" as the newspapers say, on American workmanship. I pretend, patriotically, to Gaskell, that in America nous n'en voyons pas d'autres; but, in fact, I seem to myself to recognise in it the exceptional inspiration of your wife. [Monteiro 2.27]

James's evening would not be complete without a ghost appearing in the haunted Abbey:

After dinner you are told that there is of course a ghost – a gray friar who is seen in the dusky hours at the end of passages. Sometimes the servants see him; they afterwards go surreptitiously to sleep in the village. Then, when you take your chamber-candle and go wandering bedward by a short cut through empty rooms, you are conscious of a peculiar sentiment toward the gray friar while you hardly know whether to interpret as a hope or a reluctance. (Portraits 241).

At Medley Park, Hyacinth Robinson is shown a "haunted chamber [...] where a dreadful individual at certain times made his appearance – a dwarfish ghost, with an enormous head, a dispossessed brother, of long ago" (Princess Casamassima 308). Ralph Touchett's Winchester Square abode, in The Portrait of a Lady, has a "hint of the supernatural" in the "ghostly presence as of dinners long since digested" (139). Isobel Archer, recently arrived from America, yearns to see a ghost in the old country house of Gardencourt and asks: "Please tell me – isn't there a ghost?" (46). The question is answered at the end of The Portrait of a Lady when the ghost of kind Ralph, who has just died after a long illness, appears to Isabel as a sign of comfort, not terror (578). The Turn of the Screw, James's most masterly and spooky of stories, set in a rambling country house, has a plot in which two of the characters are ghosts – the servant Peter Quint and the previous governess Miss Jessel, both most likely murdered. Like the ghost of the gray friar whom James accommodated so seamlessly and gently at Wenlock Abbey, Quint and Jesssel are alive and an integral part of Bly, a fictional country house in Essex. James's interest in the supernatural coincided with the rise of Spiritualism that gained credence in the nineteenth century with the developing telecommunications systems. The tapping or knocking of the telegraph transmitting messages across continents was thought by some to be spirits communicating. In November 1863, he had heard the spiritualist, Cora L.V. Hatch, lecture in New York. John Ruskin, too, was not immune to spiritualism in the hope of speaking to Rose La Touche.

The small, rural market town in which James found himself in 1877 was still in many ways a medieval settlement. Farms with livestock were attached to dwellings (Brook House Farm in Queen Street, in the town centre, was still a working farm in the twenty-first century). There were regular stock markets for the sale and purchase of horses, sheep and cattle, as well as general markets for fruit, vegetables, flowers, homemade cakes, pies, jams, pickles and other produce. Animals roamed around the streets: bull baiting, by dogs, was a popular form of entertainment. Waggoners and farmers with their carts and horses drove noisily up and down the cobbles.

Alongside the many timber-framed dwellings of all shapes and sizes – weavers' cottages, smithy, Raynald's Mansion, Ashfield Hall – fine, red brick, Victorian town houses for the local gentry had been built. One of these solid red brick houses was 4, Wilmore Street, the two-storey home of Dr William Penny Brookes (1809-1895), medical practitioner and surgeon. Penny Brookes was, like Ruskin, a polymath and philanthropist. He was a botanist who not only collected and recorded specimens that he kept in his many herbaria, in special cabinets with shelves, but aimed to enhance the environment by planting trees and scrubs. He took a keen and active interest in Much Wenlock. He founded the Agricultural Reading Society, mainly for local farmers, in 1841 and organised educational classes in Drawing (copying anatomical specimens), Music and Botany. For him, Physical Education was a priority, in and out of school, especially competitive sport – running, bicycle races, athletics and traditional country games. His organised games flourished and were described as "Olympian", as in "Olympian Class" and "Wenlock Olympian Society". From these local initiatives Brookes and a small committee (John Murray, the publisher was a member) founded a National Olympian Association in November 1865. In France, the great apostle of sport was the wealthy, intelligent, energetic Parisian, baron Pierre de Coubertin (1863-1937). The work and zeal of Brookes came to his attention and he visited his mentor in Much Wenlock in 1890. Coubertin, inspired by Brookes, set up a large sports federation and founded in 1896, shortly after Brookes's death, the modern Olympic movement. It is true to say that the Olympic Games were revived thanks to Anglo-French cooperation and enthusiasm. Brookes also campaigned vigorously and successfully for a railway to come to Wenlock. He is buried in Wenlock churchyard, near the tombs of the Gaskell family.

While physical health was being championed by Brookes, public health was threatened by poor sanitation. It was still basic; an open sewer (euphemistically called a brook) ran through the middle of the town, from the high ground on the Stretton Road in the west, down the High Street, past the Fox Hotel, along Back Lane, by Brook House Farm (hence the name) and across the road into the precincts of the remains of the monastery. People crossed over Rea Brook on the many wooden bridges. Even as recently as 1890, Charles Milnes Gaskell complained of "the present offensive state of the brook that passed through the town" (quoted Mumford 145). Flooding was also a common occurrence.

It was a town with many old alehouses ("publics"), hostelries and important coaching inns such as the Wynnstay Arms (now the Gaskell Arms) and the Fox. There were malthouses for the drying of hops and the preparation of ale, a safer beverage than water drawn from one of the wells with a high risk of being infected with cholera. At least two wells were dedicated to saints – to St Owen and to St Milburga. As well as honouring their piety, this was no doubt also an attempt to invoke their protection of the purity of the water and the health of the townsfolk. St Owen was an early Christian missionary who was reputed to have come to Much Wenlock, from Brittany, in the sixth century. St Milburga was the second Abbess of the early Wenlock monastery for both monks and nuns founded around 680 by her father King Merewalh of Mercia.

In Portraits of Places James described Much Wenlock as "an ancient little town at the abbey-gates – a town, indeed, with no great din of vehicles, but with goodly brick houses, with a dozen 'publics', with tidy, whitewashed cottages, and with little girls [...] bobbing curtsies in the street (239)".

Last modified 16 March 2020