Photographs and scans by the author, with many thanks to Helen Elletson, curator of the William Morris Society, for answering my questions. You may use all but the last image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the source and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Two views of Kelmscott House, 26 Upper Mall, Hammersmith, London W6 9TA, from both approaches. On the left can be seen the little coach-house now used by the William Morris Society.

William Morris took a lease on this stately later eighteenth-century house, which is now a Grade II* listed building, in 1878. From then on it was his town residence. "Before going out to Italy he had arranged to take a new house," says his early biographer, James Mackail, "a large Georgian house, of a type, ugly without being mean, familiar in the older London suburbs" (I: 371; few would call it ugly now). The house already had a proud history: once the home of Francis Ronalds, the first person to have sent a communication by cable, it had had "eight miles of insulated wire" laid down in the garden (MacGregor 271); but its most recent tenant had been the author George MacDonald, who lived here from 1867-77, and wrote two of his children's books during that time: At the Back of the North Wind (1871) and The Princess and the Goblin (1872).

Morris changed its name from The Retreat to Kelmscott House, after his much-loved Oxfordshire residence, Kelmscott Manor. The Hammersmith house also faced the Thames, and "[h]e liked to think that the water which ran under his windows at Hammersmith had passed the meadows and grey gables of Kelmscott; and more than once a party of summer voyagers went from one house to the other by water, embarking at their own door in London and disembarking in their own meadow at Kelmscott" (Mackail I: 372).

The coach-house annexed to the main building, from Upper Mall

The coach-house was to be useful for a workshop, and later a talks venue. Here Morris first launched into carpet- and rug-making:

The coach-house and stables adjoining the house were converted into a large weaving-room.... Carpet-looms were built there, and were soon regularly at work producing the fabrics which became known under the name of the Hammersmith carpets and rugs from this accident of their first origin. During the winter of 1878-9, in fad, weaving in its various forms on the Jacquard loom for figured silks, on the carpet-loom for pile carpets, and on the tapestry-loom for Arras tapestries replaced dyeing as the chief object of Morris's interest. [Mackail I: 373-74]

Morris kept a diary of his "Acanthus and Vine Tapestry," showing that he worked on it at his own personal loom, a small one that he kept in his bedroom rather than in the coach-house, for nine or ten hours a day. It was a labour of love for the house itself. Of course, his mind was not idle as his hands worked: "If a chap can't compose an epic while he is weaving tapestry, he had better shut up; he'll never do any good at all" (qtd. in MacGregor 275; see the last picture on this page).

Later, when Morris had turned his attention towards dyeing, and acquired works premises at Merton Abbey in 1881, the weaving-room was used as the meeting-place of the Hammersmith Socialists:

The conditions of membership in the Society were limited to a general agreement with the principles of Socialism, as explained in the manifesto to be issued by it, and a payment of a shilling as annual subscription. Its object was defined, or was left undefined, as the spreading of the principles of Socialism. Its place of meeting was named as being at Kelmscott House, and a few simple regulations as to officers and candidates made up the remainder of its constitution. Mr. E[mery] Walker was, and still is, the secretary of the Society. Morris himself was treasurer. The old room in Kelmscott House continued to be at the service of the members for meetings, which were held twice a week for several years. As time went on they became more intermittent; and at last the Society continued to exist only in the sense that it never was formally dissolved. [Mackail II: 240]

Emery Walker, the printer and fellow-Socialist, lived just a few minutes' walk away along the river in a house at Hammersmith Terrace, as did another important figure associated with the society, T. J. Cobden-Sanderson, bookbinder, who gave the name to the Arts and Crafts movement and founded the influential Doves Press. Both have plaques on their houses now, and Emery Walker's house is open to the public.

The Garden

Left: View from the coach-house window, showing part of the original lower garden. Right: The upper part of the garden, looking towards the house, in a watercolour painted by Jessie MacGregor. Source: MacGregor, facing p.292.

As usual, Morris's inspiration came from nature. In fact, even though Upper Mall, Hammersmith, was a town address, it was by no means in the heart of the busy metropolis. "It is only separated from the river by a narrow roadway, planted with large elms," explains John Mackail. "On bright days the sunlight strikes off the water and flickers over the ceilings: many barges and sailing boats go by with the tide, and the curve of the river opens out two long reaches, up by Chiswick Eyot with the wooded slopes of Richmond in the background, and down through Hammersmith Bridge" (I: 371). Moreover, "[b]ehind the house," Mackail continues, there is a "long rambling garden, in successive stages of lawn and orchard and kitchen-garden," which at that time still preserved "some flavour of the country among the encroaching mass of building which is gradually swallowing up the scattered cottages, low and roofed with weathered red tiles, that then lay between the river and the high road" (I: 373). Writing to his wife, Morris said the situation

is certainly the prettiest in London ... the garden is really most beautiful. If you come to think of it, you will find that you won't get a garden or a house with much character unless you go out about as far as the Upper Mall. I don't think that either you or I could stand a quite modern house in a street: I don't fancy going back among the bugs of Bloomsbury. [qtd. in Mackail I: 372]

Some of the garden is still left, not only the little lower garden, but also "the upper walled garden," with "lawns, shrubs, flower beds and trees, many of them plants mentioned in Morris's writing of his garden in the 1880s and '90s" ("Kelmscott Garden").

The Interior

This area, down some steps from the coach-house in the basement of the main house, was the servants' hallway in Morris's time.

The lower hallway, accessible from the coach-house, can only give a glimpse of the way the Morrises used to live. Now used by the William Morris Society, it is has a lovely fireplace, tiled with the original blue-and-white tiles put in by Morris, and thought to have been designed by Philip Webb. The walls are plain but glowingly painted; and the generously-sized table, which can be augmented by the addition of two side-tables, was made by the Walnut Tree Workshops (no longer in existence) to match the existing furniture, in an Arts and Crafts style. Some rich Morris-designed textiles are on view. A little room at the side was once the Morrises' laundry room, and one at the very front of the basement was previously the kitchen.

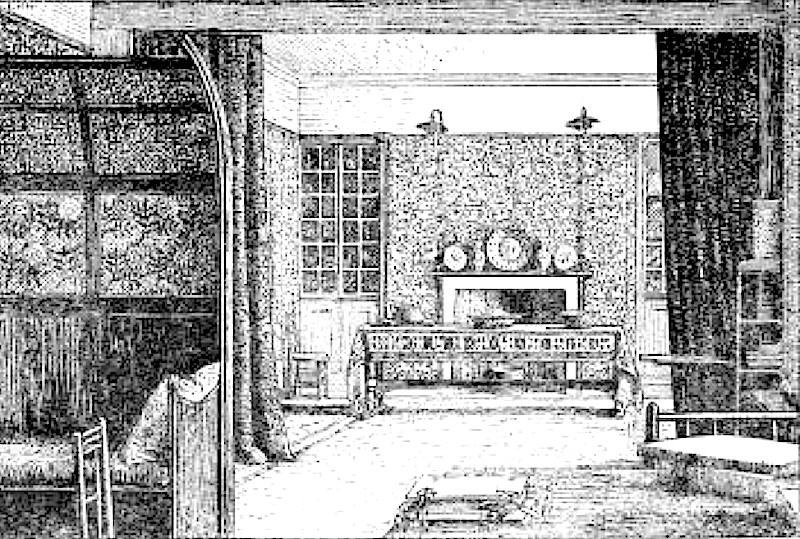

The drawing-room, from an illustration by E. H. New in Mackail I, facing p. 372.

The main house is now in private ownership. It has a lovely large through drawing-room, "a handsome room with a range of five windows, filling the whole width of the house and looking out through the great elms over the river." According to Mackail, Morris had made this room

quite unique in the quietness and beauty of its decoration. It was sufficiently out of the London dirt to admit of being hung with his own woven tapestry. The painted settle and cabinet, which were its chief ornaments, belonged to the earliest days of Red House; the rest of the furniture and decoration was all in the same spirit, and had all the effect of making the room a mass of subdued yet glowing colour, into which the eye sank with a sort of active sense of rest. [I: 372-73).

In contrast, Morris's study on the ground floor was very plain — "severely undecorated," says Mackail. "It had neither carpet nor curtains; the walls were mostly filled with plain bookshelves of unpolished oak, and a square table of unpolished oak scrubbed into snowy whiteness, with a few chairs, completed its contents (I: 372-73).

© The Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Morris's pencil and watercolour cartoon for the "Acanthus and Vine" design used in the tapestry that he wove on the small loom in his bedroom at Kelmscott House. Only half the pattern has been fully worked out here. The task took him four months, and "no less than 516 hours" (Hunter 239).

Morris was fond of his town residence, and missed it when he was away at Kelmscott Manor – particularly the work he did there. "How nice it will be when I can get back to my little patterns and dyeing, and the dear warp and weft at Hammersmith!" he wrote on one occasion (qtd. in Mackail I: 375).

Related Material

Sources

Hunter, George Leland. Decorative Textiles: An Illustrated Book of Coverings for Furniture, Walls and Floors. Philadelphia and London: J. B. Lippincott, 1918. Internet Archive. Contributed by the University of California Libraries. Web. 2 April 2015.

"Kelmscott House." English Heritage. Web. 2 April 2015.

"Kelmscott House Garden." London Gardens Online. Web. 2 April 2015.

MacGregor, Jessie. Gardens of Celebrities and Celebrated Gardens in and around London. London: Hutchinson & Co, (?) 1919. Internet Archive. Contributed by the University of California Libraries. Web. 2 April 2015.

Mackail, John William. The Life of William Morris. Vol. I. New ed. London and New York: Longman, Green and Co., 1901. Internet Archive. Contributed by New York Public Library. Web. 2 April 2015.

_____. The Life of William Morris. Vol II. New ed. London and New York: Longman, Green and Co., 1901. Internet Archive. Contributed by New York Public Library. Web. 2 April 2015.

Created 2 April 2015