This review is reproduced here by kind permission of the online inter-disciplinary journal Cercles, where it was first published. The original can be seen here. It has been reformatted and illustrated for the Victorian Web by the author. Click on all the images to enlarge them, and usually to find out more information about them.

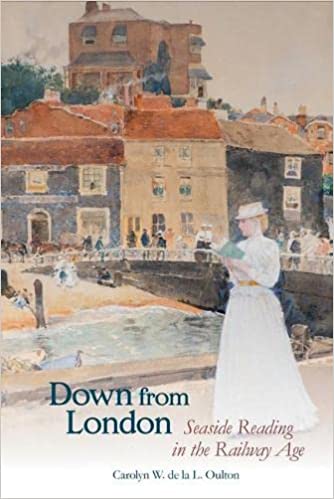

arolyn W. de la L. Oulton's Down from London has a particularly beguiling cover, featuring a watercolour entitled Bleak House, Broadstairs (1889) by the nineteenth-century American artist, Childe Hassam. It depicts a young woman in a light summer dress strolling along the promenade, looking to neither right nor left, but lost in her book instead. Looming above her, on its headland, is Fort House, popularly referred to as Bleak House since the 1860s, because Dickens and his family had several times spent part of their summers there. In most respects, this picture is spot on. It was the golden age of the seaside resort, when literary tourism became fashionable, and when a whole new interest in "holiday reading" developed. The intersection of these trends is Oulton's subject here, and she organises a huge amount of diverse material in two main ways — by looking at the seaside itself and the kinds of books being read there, and then by examining specific resorts in the south-east of England, such as Brighton, Folkestone and Margate, where the seaside culture flourished. Broadstairs itself comes to the fore in the last chapter, devoted to "Writing the Dickens Country."

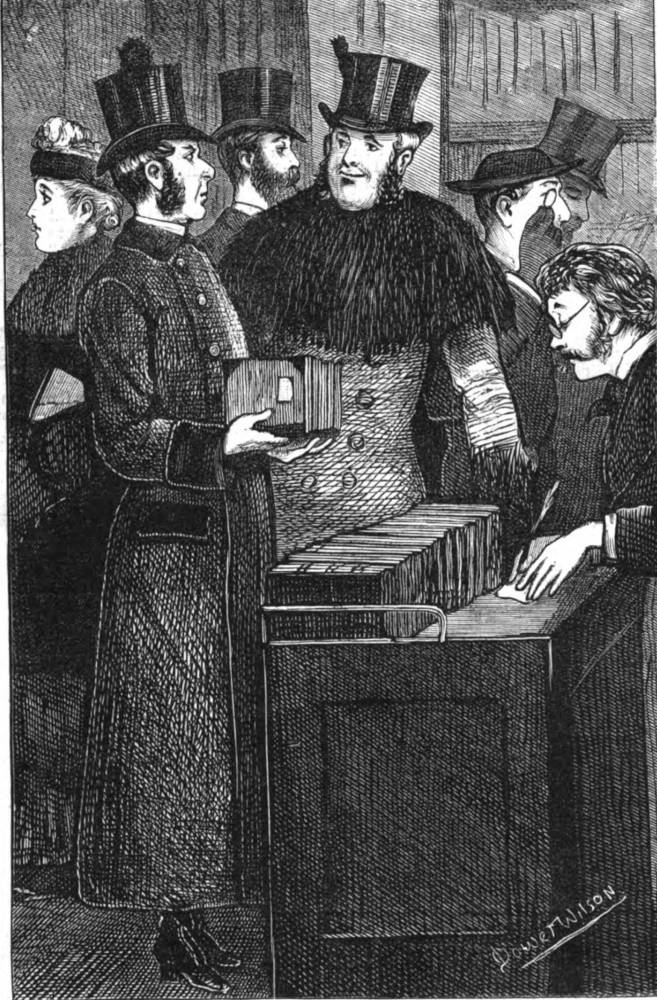

At Mudie's, by Dowett Wilson, shows two footmen picking up books, and discussing the different tastes of the women in their respective households: one family prefers sensational novels, the other likes piously moralistic ones — which hardly anyone else ever reads.

People set out for the seaside with a variety of books, sometimes picked up at railway station stalls, or sometimes brought from home. Despite the additional burden it entailed, choosing most of them before the trip was recommended. An article in the Birmingham Daily Post advises, "the best plan is to put the books into a wooden library-box (like one of Mudie's), which holds twelve to twenty volumes, is easily opened and carried, and which goes under the seat of a railway carriage" (qtd. p. 20). How the most voracious readers would have benefited from today's light-weight eBook devices! Still, there were ways of getting round the problem of luggage, and not just by calling a porter. On arrival, summer visitors could patronise one of the local libraries, an ideal recourse on a rainy day, or help the local economy by purchasing guidebooks and periodicals that were lighter in every sense than the kind of hefty tomes that might constitute their regular fare.

As for libraries, Parson's Library in Folkestone not only had "the finest selection of books of all descriptions," but "a delightful lounge, where subscribers may rest, meanwhile perusing at will the large selection of newspaper and magazines" (qtd. p.144). This was a subscription library, but Folkestone's Free Library, established in 1879, allowed borrowing as well as reference from 1881, and was criticised for offering (horror!) more "modern works of fiction" (qtd. p. 149). Specifically for the tourist market, guidebooks proliferated, while Summer Thoughts for Happy Holidays, the summer number of a penny journal, was promoted as being "Cram full of funny pictures and side-splitting jokes..... The book for the beach par excellence" (qtd. p. 19). Bought at the resort, acquisitions like these were eminently portable, and could perhaps jettisoned before departure. Such details offer useful insights into life in the late Victorian seaside resorts.

Copy of Dr Syn in the Internet Archive, digitalised from

a book in the Boston Public Library system.

Given its variety, Oulton, like the Victorian columnists and feature-writers who offered recommendations, finds "holiday reading" hard to categorise: "it was always prone to splinter in confusing ways between educational popular science, illustrated humour, and light or sensational fiction" (75). One advantage of Oulton's attempts to cover this field is that she often deals with non-canonical, even ephemeral work, thus opening up new ground. Discussing the sea itself in her first main chapter, for example, she looks, among others, at fast-paced books about smuggling. Rather than contenting herself with Daphne Du Maurier's celebrated Jamaica Inn (1935), she pays equal attention to the tales of Russell Thorndike, a now largely forgotten Kentish author. Thorndike's first Doctor Syn book came out in 1915, and led to a series of prequels in which the roguish hero, the vicar of the fishing village of Dymchurch-under-the-Wall, uses his expertise in smuggling to help his parishioners. His favourite sea-shanty, introduced in the second chapter of the original book, gives you a flavour of the series: "Oh, here's to the feet that have walked the plank; /Yo ho!" It is exhilarating to meet such new characters, and Oulton opens up many fresh avenues for research. Happily, Dr Syn himself is quite well represented in the Internet Archive, where Thorndike's work is variously marked as Pulp Fiction, Miscellaneous, Adventure, and Popular Magazine! Oulton says that she has looked at "approximately 130 novels and stories set at least partly on the UK coast" (221), so there is a real feast of such non-canonical fare.

Left: Fashionable visitors in the Gothic interior of the Brighton Aquarium, in August 1872. Right: Outside the aquarium area, with the Chain Pier in the background, a photochrom print dated between c.1890 and 1900.

The resorts were rather easier to categorise than the reading that went on in (or indeed about) them. Each seaside town had its own character, although their reputations tended to change with the times. Folkestone had rather a superior status, and was keen to keep it that way, by appealing to the "more genteel" kind of visitor (10). Brighton, sometimes known as London-by-the-Sea, was a mixed bag like the capital itself: by the Victorian age it had become "fashionable but also fast, a health resort with accepted credentials that also had an unusually high rate of poverty and disease emanating from its backstreet tenements" (108). One marker of gentrification, Oulton suggests, was the arrival of a pier: Brighton's Chain Pier was opened as early as 1823, and is immortalised in one of John Constable's paintings. So many of the holiday-makers here were drawn from the upper classes that a journalist in the Graphic commented wryly in 1889 that "the visitors are more attractive than the place itself" (qtd. p. 114). Resorts on the Isle of Thanet lost out accordingly: by the mid-nineteenth century, Ramsgate and neighbouring Margate were left largely to the lower classes. Margate in particular became (in William Hughes's words in A Week's Tramp in Dickens Land, first published in 1891) "a popular Cockney watering-place" (qtd. p. 213). So much for the idea, voiced by an MP in Folkestone on the relocation of the free library there, that such spaces could promote "the greater union of class with class" (qtd. p. 148). The most that can be said in that respect is that, now that the railways had made the south coast so easily accessible, "remaining exclusive" was becoming more of a challenge (222).

Left: "Bleak House" overlooking Broadstairs today. Right: "Betsey Trotwood's Parlour" in the Dickens Museum on the seafront at Broadstairs.

After following Oulton rather breathlessly through an accumulation of detail, and across some very permeable boundaries, it is quite a relief to land on familiar Dickensian territory in the last main chapter. Here we find that the title of Childe Hassam's painting is the only misleading aspect of it: Dickens did not write any part of Bleak House in the Broadstairs mansion. Rather, it was where the later chapters of David Copperfield were composed. Nevertheless, the idea that it inspired Bleak House persisted into the twentieth century. The challenges as well as vagaries of promoting literary tourism are also illustrated by the belated identification of a certain sea-front cottage in Broadstairs as the inspiration for Betsey Trotwood's home in the same novel. Yes, it answers well to the description in David Copperfield, and is now set up as a museum, with Betsey's front parlour cleverly recreated here. But this was only after a long period of confusion, because Dickens himself had relocated it to Dover in the novel.

As Oulton says, "The history of seaside reading is a complex one" (221) and she has had some difficulty in packing her large amounts of information into discrete chapters. Not that it matters. Given the nature of her material, there was bound to be some overlap, and there is much here for social historians and literary enthusiasts of all kinds to enjoy dipping into, unpacking and following up. Unfortunately, the steep price may limit the readership. The publisher would do well to make a more reasonably priced paperback edition available — hopefully, with the same appropriate illustrations and, of course, cover design!

Bibliography

Oulton, Carolyn W. de la L. Down from London: Seaside Reading in the Railway Age. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2022. Hardback ed. xi + 272 pp. ISBN 978-1-80085-401-1. £95.00

Created 17 March 2022