This review is an extended version of one originally published under the title of "Mother Knows Best? A Victorian Dispute about Parenting" in the Times Literary Supplement of 15 August 2025. Page numbers, illustrations, captions and links have been added: click on the images to enlarge them, and for more information about them.

n October 1854, Elizabeth Gaskell went to stay with the Nightingales at Lea Hurst, their picturesque country home in the Derbyshire hills. Now in her mid-forties, the novelist was the busy wife of the minister at Cross Street Chapel in Manchester, and the mother of four children aged between 8 and 20. She was taking advantage of Fanny (Frances) Nightingale's invitation to enjoy a "pause" from her domestic duties, so that she could get on with writing her fourth novel, North and South. This was already being serialised in Charles Dickens's journal, Household Words, and, to her annoyance, Dickens had been "complaining that some of her early dialogues were too long, and asked her to make cuts" (55): he was keen for the narrative to move on more rapidly. With more than a hint of irritation, she told him later, "Don't consult me as to the shortenings, only please yourself" (60)

Notice in the Household Words of 2 September 1854, at the end of the first part of the serialisation (chapters 1 and 2), p.72.

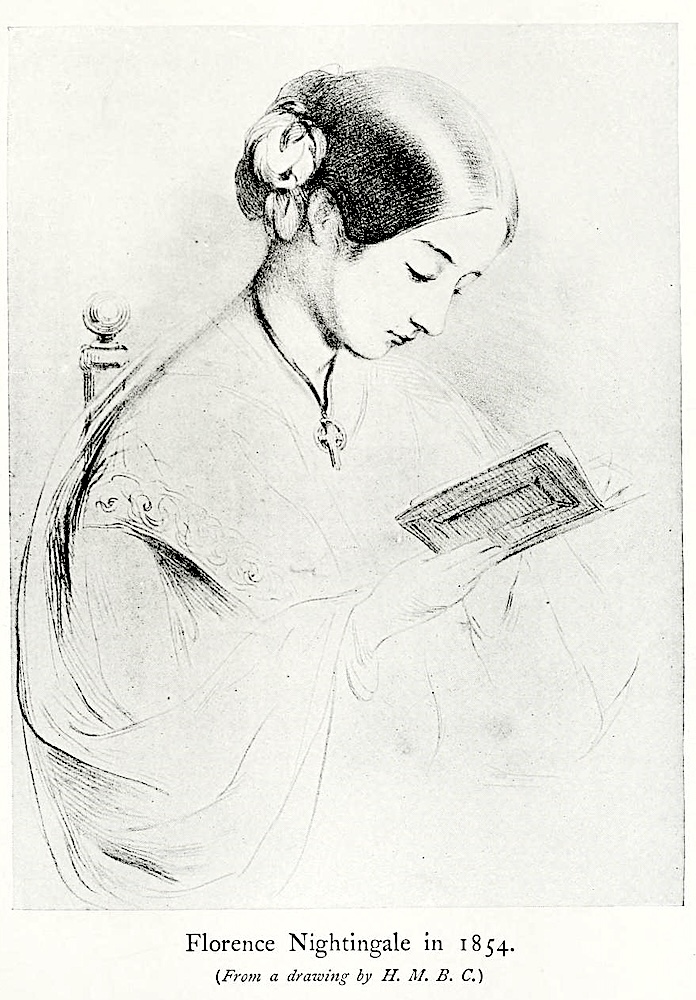

The pressure to write her novel in serial form, under "the cruel necessity of compressing it" (60), was keenly felt. Still, she revelled in her rural retreat: "I am writing overlooking such country!" she enthused to her friend Catherine Winkworth (18), describing the view from her window in close detail. And indeed her stay started off well — and sociably — enough. She had met Fanny herself years ago in London. Now she got to know her daughters. The younger one, Florence, some ten years her junior, was "taking a break from an intense summer of nursing" (89) and proved to be an entertaining companion, with a gift for mimicry. Elizabeth listened eagerly to the younger woman's account of her experiences, passing it all on to another friend, Emily Shaen, with evident admiration: "She has been night-nurse and day-nurse — housekeeper (and reduced the household expenses one-third from the previous housekeeper), mixer-up of medicine, secretary, attended all the operations" (89). Here indeed were the seeds of Florence's future success, and in fact she was now right on the cusp of her extraordinary career, and the fame that it would it bring: she had just been commissioned to take a team of nurses out to the Crimea. Elizabeth, whose third novel, Ruth, had courted controversy by its sympathetic treatment of the "fallen" heroine, was naturally impressed by this capable young person with her strong sense of mission. If she guessed, as perhaps she did and as Stadlen explains in Chapter 5, that Florence's choice of career had been made in the teeth of strong familial opposition, it would only have increased Elizabeth's admiration for her.

Florence Nightingale in 1854, from a drawing by "HMBC" [Hilary Bonham Carter, Florence's cousin] in Matheson, following p. 112.

The two women had much in common, not least a strong motherly instinct. What could possibly go wrong between them? Naomi Stadlen, herself an unhurried and thoughtful story-teller, creates suspense by building up only gradually, over the opening chapters, to the "grand quarrel" of the title. A psychotherapist by profession, with several previous books on motherhood, Stadlen first brings out the differences between the two women's early experiences. Elizabeth had been little more than a year old when her own mother died, and, despite being part of a larger and loving family unit, had written later of "the craving one has after the lost mother" (30). When her own daughter Marianne was born, Elizabeth saw her as a "blessing from God" and "an individual person" in her own right (38). As a mother herself, she had been so deeply involved in the experience of motherhood that she had written a diary about those precious early years. Observing and cherishing every detail of her baby's development, she revealed the profound bond between the two of them, and a touching respect for the individuality that she encouraged and valued. In contrast, Florence and her elder sister Parthenope had been brought up by their own mother — but Fanny's expectations for them had proved restrictive. Of her father too Florence wrote tellingly, "He never cared what I was or what I might become" (73). Even between the two sisters, there had been "turbulent years of family conflicts" (77).

Little wonder, then, that in the climactic seventh chapter, Elizabeth's belief in the importance of the mother-child bond, a belief that permeated her writing as well as her life, was met by Florence with a stubborn insistence that babies would do better in a crèche. Rather disappointingly for us now, Elizabeth herself gave no details of the conversation which she described at the time as a "grand quarrel." She simply included a brief account of it in her long and otherwise glowing letter to Emily Shaen. But her hostess's daughter, she revealed, went so far as to insist that "if she had influence enough not a mother should bring up a child herself" (105). As Stadlen says, Florence had studied the classics with her father, and may have had in mind here Plato's ideas in Book V of The Republic: "The offspring of the good, I suppose, they will take to the pen or crèche" (section IX). But it is hard to not to sense in Florence some bitterness about her own parents, and their expectations of her — and in her listener's report, some indignation about such a sweeping statement. Although Elizabeth quickly goes on to tell her friend about Florence's "utter unselfishness in serving and ministering" (105), she does seem to have taken their difference of opinion as a personal affront, and to have felt snubbed by the younger woman.

Florence left soon afterwards on the mission that would define her, and it would be over two years before the pair made contact again. This was unfortunate, because the two do not appear to have harboured any ill-feeling about the contretemps. In Chapter 8, we learn that Florence wrote home from Scutari, "Do send me this year's numbers of Household Words. I want to read North and South. It rests me" (113). Shortly afterwards, Elizabeth in turn wrote to Parthenope, "I often think of you & her, & you all. You'll let me have one line to say how she is" (114). Even on motherhood, the two were not really far apart in their thinking. "Elizabeth and Florence were both, in their different ways, maternal," says Stadlen (150). Just before coming to Lea Hurst, Elizabeth had written the chapter in North and South in which her heroine, Margaret Hale, appeals for kindness towards the striking millworkers; her "humane, maternal voice" (149) would soon find a parallel in Florence's pleas for the better treatment of "her" wounded soldiers at Scutari. Moreover, years later, experience taught Florence to be more forgiving of her own parents. As time went by, she also came to believe that, after all, "children can only be brought up in families. There is a subtle sympathy between the mother and the child which cannot be supplemented by other mothers" (130).

The issue of how best to rear the future generation is, of course, one that still resonates strongly with us. In her second part, "Mothers Today," which consists of a tenth chapter entitled "Where Have All the Mothers Gone?" Stadlen explores the experience of motherhood in our own times, and makes a direct and intimate appeal to all her readers. "'Really good kids'" don't drop down from the sky", she says, "They are nurtured" (186). She is surely right to claim that many women would prefer not to have to delegate this vital job to others, and are only forced to do so by financial necessity. Would it not be in society's best interest, she asks, to ensure that there is a viable alternative, and to value and support those who opt for it?

Many critical books are aimed at select audiences within the academic sphere. But Stadlen's insights into Elizabeth Gaskell's novels, particularly into her struggles with the serial form of North and South in Chapter 4, as well as her tracing of Florence Nightingale's career, make this book rewarding for students of literature and history alike. Her reflections on the disagreement between two pioneering Victorian women, both of them in their own ways willing to risk criticism for their beliefs, also give her research a focus and interest for non-specialist readers. It is so sad to learn that the author passed away just after seeing the first copy of this very readable and well-informed book, the last of her five works on motherhood (and grandmotherhood), in print.

Bibliography

[Book under review] Stadlen, Naomi A Grand Quarrel: Elizabeth Gaskell, Florence Nightingale and Mothers Today. London: Montag & Martin, 2025. 207 pp. pbk. £14.99. ISBN: 978-1-78066-820-8

[Illustration source] Household Words. Vol X (August-January 1854-1855). 1855. Notice on p.72 at the end of Chapters 1 and 2 (the first instalment). Internet Archive, from a copy in the Wellcome Library. Web. 1 December 2025.

[Illustration source] Matheson, Annie. Florence Nightingale: A Biography. London: Nelson, 1913. Internet Archive, from a copy in the University of California Libraries. Web. 1 December 2025.

Created 1 December 2025