Emily Faithfull read this paper at the Royal Society on the 29 March 1871 (see note at the end, and bibliography, for publication details). When the figures for the 1871 census came out, they only served to strengthen her argument for the employment of women. She notes at the beginning that this was already a "well worn subject" but goes on to argue convincingly against deeply entrenched views about it. She makes particularly pertinent comments on contemporary attitudes to women's roles, especially about middle-class women's own expectations. Faithfull also gives useful details about, and figures for, women's occupations — and points out that men often worked in areas that would seem to have been more suitable for women. Presumably, domestic service is covered by category II below, where it is seen as employment by "man"; nursing is not mentioned at all. But of course the emphasis is on skills that could be used in industry. — Jacqueline Banerjee

Paragraphing and subheadings were added when formatting the paper for the Victorian Web, for ease of reading.A few illustrations, and links to other material on our website, have been added. Page numbers are given in square brackets.

have responded to the invitation to read a paper upon this well worn subject, because, in spite of familiar facts and figures to which I shall presently refer, I believe that considerable misconception prevails, not only as to the real end and aim of those who are actively interested in what is generally called “the movement for women,” but a misconception which extends to the raison d'être of the movement itself. And, indeed, the divers claims which are put forth, sometimes as rights, and occasionally as duties, together with the loud and repeated cries for enfranchisement, which are starting up with singular rapidity on all sides of us, must sound more or less unmeaning, according to our ability [3/4] to comprehend the central necessity from which they all really emanate. In whatever spirit we approach the subject, either as an antagonist or as an advocate, a calm and impartial inquiry cannot fail to be useful to us all; and I certainly venture to hope that the few statements which I have to make — the result of some years’ work in this direction — will elicit a discussion, without fear or favour, which may tend to throw some new light upon a very difficult and perplexing problem.

I am quite aware that to many people this topic is utterly distasteful; but in addressing the members of the Society of Arts, I feel I am not speaking to persons who tremble at the “lightest rustle among the leaves of their prejudice,” but to thoughtful men and women, clear sighted enough to see the necessity of dropping theories and ideals, however pleasant, and the absolute importance of looking at things as they really are, - men and women who are able and willing to help in overcoming that moral panic which is often sufficiently powerful to retard a new suggestion from even undergoing an experimental test. Without further preface, I shall therefore proceed with the subject of my paper. But, that we may start with a thorough understanding, permit me at once to say, that I do not for one moment seek to remove women from those household duties which seem so naturally to come within their special sphere. I have, I may say, in common with most sensible persons, some very strong opinions respecting the thorough performance of domestic work; I will yield to no one in my belief of what a woman can and ought to make a home; but it must be remembered, that I have undertaken this evening to deal with those who have, so to speak, no domestic duties, and no household, but such as they can maintain by personal labour.

Numbers of Women in Employment

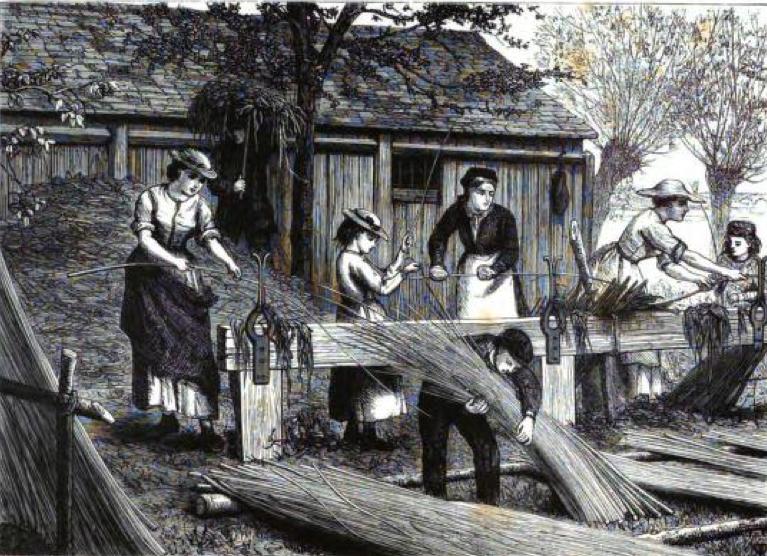

Women working in the countryside, osier-peeling, at around this time.

That this class is at least large enough to demand our solicitude will be proved by a glance at some statistics, drawn up from the census of 1861, by the Secretary of the Society for the Employment of Women, a society which was set on foot some years ago, and which has now received Her Majesty's sanction and support. In 1861, 6,727,697 Englishwomen over 15 were returned, of whom 3,249,872 were working for wages. These are distributed in the following manner:—

I. PROFESSIONAL CLASS

II. DOMESTIC CLASS

III. COMMERCIAL CLASS

IV. AGRICULTURAL CLASS

V. INDUSTRIAL CLASS

VI. INDEFINITE CLASS

Total.... 3,249,872

When the census is taken in April, I believe that this total will be considerably enlarged; anyhow, in the face of these startling figures, it is impossible to maintain that those who are trying to open new paths for female industry are suddenly transplanting women from quiet domestic offices, and bringing about a social revolution fraught with danger to the whole community.

Work in Factories and Mills

Future missionary teacher Mary Slessor as a young woman working in a Dundee jute mill. Largely self-taught, she went out to Africa as a missionary teacher in 1876.

The simple fact of the case is, that the women of what we term the labouring class have always had a certain share in the occupations of their fathers, husbands, and brothers. There is no deeply-rooted dislike to their admission into industrial pursuits, although there is a considerable difficulty in securing for them a fair chance of rising to situations of responsibility and consequent importance. It is true that you find women in our various chemical works, glass-houses, rope works, paper mills, glue works, and earthenware factories, but there you find them employed in the lowest and worst-paid departments. You will find women in the blowing rooms of our cotton mills, for example, where, to accommodate themselves to the high temperature, they usually work in a half-naked condition. Closely allied to the cotton manufactory, though not exactly forming part of it, is the occupation called waste-cleaning. The refuse of cotton mills — the sweepings — full of dust and filth, are [5/6] bought up by certain dealers, and put through machinery in the process of cleaning. The women and girls employed in this have to work in such fearful clouds of dust, that they are forced to fill their mouths and nostrils with rags and cotton to avoid suffocation; and when they leave work they are literally covered with a layer of greasy dirt and dust.

In hundreds of factories where women are employed, there is work going on of a lighter and less unsuitable kind than what they are actually doing. When I proposed, in 1859, to open a printing-office for women, I was told that setting up type would degrade and injure them, and that I could scarcely suggest a more unsuitable employment; yet, even while these warnings were being given me, girls were extensively employed, in an inferior capacity, in printing establishments as machine feeders; a branch of the business which appeared to me so unsuitable, that I never allowed it to be undertaken by girls in the office I eventually started for female compositors. I said just now, that while women were widely admitted to these industrial pursuits, they seldom obtained positions of trust and management; but I am glad to make an honourable exception of the Birmingham button manufactories, in which they are frequently to be found as overseers, and where they are, consequently, in receipt of high weekly wages. The reason for the rule is not, I think, hard to find. The exclusion of women from the higher departments of trade must be traced, in a measure, to the same feeling which compelled Dr. Elizabeth Garrett to seek in Paris the qualification to practise as a physician, which in spite of her manifest ability to do so, was denied her by the London College of Physicians. The same mistaken policy sends us to Switzerland for so many of our watches; and by it our women are also prevented (or were so up to a very recent period) from pasting patterns of floss silk upon cards, and forbidden in the porcelain potteries in Staffordshire to use the hand-rest.

Employment at the Lowest Level

But the exclusion of women from the most remunerative branches of labour is also due to the absence of special mental training. I have been told repeatedly, when commenting on the unsuitable work executed by women in comparison with the lighter and more feminine occupations engaged in by men in the same factories, that the work could be done by women, but that as it required an apprenticeship, women were never permitted to undertake it. Now, however we may view apprenticeships, it is clear that no skilled work can be done without definite training of some kind, and as women seldom, if ever, secure anything deserving the name, they are naturally excluded from skilled work and its advantages, [6/7] and it is difficult to estimate the depressing effects of a system which deprives the working woman of a stimulus found of value even to the most conscientious and cultivated man in the kingdom. It is not marvellous that women so often perform work mechanically, as a matter of routine, without intelligence or spirit. I shall abstain from entering at any length on one very serious consequence of this restriction of women to the inferior branches of industry, but I feel it right to say, in passing, that as it deprives the younger workers of the supervision of their own sex, I cannot but regard it as a great evil. If girls saw older women in positions of trust and authority, they would not only be encouraged to develop that business-like capacity and those qualities of character without which they must remain socially and individually in the lowest scale, but they would feel themselves far more protected than they can do at present, while they have no other safeguard than their own prudence.

The points I wish to establish in relation to this portion of my subject are, in short, as follows:–

1. That as women are so extensively employed in industrial pursuits, they ought not to be deprived of the advantages of systematic training, nor excluded from the most lucrative branches of the various occupations in which they engage.

2. That we are not justified in drawing upon their physical strength, and ignor ing their mental capacity to the extent which at present obtains amongst us.

3. That it is a mistake to regard women as mere machines — hands without heads.

And, lastly, that while society is loud in objecting to the gnat, it has long since quietly swallowed the camel.

Women Left Behind

William Rathbone Greg's book of 1869, published in London by Trübner, which suggested that women had come to seem "redundant" after the demise of the spinning wheel.

We have, however, to view the matter from another point. The working women of whom we have been speaking have at any rate been able to follow, after a humble fashion, the avocation (once entirely carried on by women in separate households) into the huge manufactories into which they have been transplanted, by the application of masculine science to what was once only feminine work. But the introduction of machinery has affected the fortunes of another and higher class in a still more disastrous manner. As long as the sound of the spinning wheel was heard in every home, there was profitable work to be done by every member of each household, and our “redundant involuntary celebates,” as Mr. W. R. Greg calls them, could find shelter with their kith and kin, without the uncomfortable conviction that they were either useless burdens or idle drones. This class is a large and ever-increasing one, and seems to have dropped altogether out of the great onward march of humanity.

Teaching

Owing to the change which has taken so much feminine work into [7/8] our large centres of industry, the women who belong to it are left to provide for themselves, and society has at present taken but little trouble to enable them to do so, either by education or by opening the doors to salaried employment. The one means of self-support which has been open to the destitute gentlewoman has been the profession of the teacher, and into that all the unmarried and fortuneless daughters of clergymen, merchants, doctors, military and naval men, all rush, as the only channel of which their social prejudices admit, or in which their utter incapacity gives them any chance of success. For thirteen years, I have had an office which brings me into communication with ladies of this description, and I seldom receive applicants for remunerative employments without hearing their apologies “for being compelled to teach,” in consequence of a bank failure, a father's death, or some unexpected circumstance; while some do not hesitate to tell me that “they hate teaching,” but prefer to become governesses rather than lose status by taking part in some industrial pursuit. But even this “status” appears to me entirely imaginary, for the majority of those who employ them have still an unpleasant habit of looking down upon a lady in this capacity, as “only a governess.”

To prove that I am not singular in this opinion, allow me to quote the following passage from one of Mr. Ruskin's well-known lectures:—

What reverence do you show to the teachers you have chosen? Is a girl likely to think her own conduct or her own intellect of much importance, when you trust the entire formation of her character moral and intellectual, to a person whom you let your servants treat with less respect than they do your housekeeper (as if the soul of your child were a less charge than jams and groceries), and whom you yourself think you confer an honour upon by letting her sometimes sit in the drawing-room in the evening?

I need not point out the injury inflicted on the whole profession, which not unnaturally suffers from the faults of the mass of its numbers, for nearly everyone is now aware that it has been little honoured and ill remunerative, because numbers enter it who are utterly unfit to discharge its duties. These incompetent persons cannot be excluded until the public has learned to require certificates of ability. They have long been in use on the continent, and I hope the day will shortly come when they will be indispensable to every English teacher. But, in the meantime, we must try to open less thronged and foot-worn tracks to meet the pressure of the present state of things. During the last few years, efforts have been made in various directions with more or less success.

Printing

Emily Faithfull's own Victoria Press, successfully established in 1860.

With regard to the experiment of printing, to which I have already referred, I am glad to find, from a recent number of the Press News, a recognised trade-journal [8/9], that the “idea is extending,” and “that it cannot be denied that we have by far many more female printers, both earning their bread by wages, and investing their capital as employers, than ever we had.” The Post-office now employs about 1,000 women as telegraph clerks, and as an earnest of Mr. Scudamore's intention to increase this number, I may mention that he has organised a class of instructresses, an office unknown under the companies. In Telegraph Street alone, 485 young women are employed, and the heads of the department bear high testimony to their admirable industry, quickness, and intelligence: the ordinary payments made to them range from I0s. to 22s, according to proficiency, and as clerks in charge they receive from 25s to 40s. The central office is at present rather too crowded, owing to want of space, but the general arrangements evince a very thought ful consideration on the part of the managers. Candidates for telegraphy must be between the ages of 14 and 20, must write a good legible hand, spell and read quickly, and thoroughly understand the first four rules of arithmetic; they must possess good eyesight; and the know ledge of a foreign language is a great advantage, but by no means requisite.

Hair-Dressing

Hair-dressing is another business steadily opening to women. I well remember in the summer of 1858 asking several London hairdressers to teach women to cut and dress hair, but I was told it was quite impossible, and various plausible reasons were assigned for this opinion, and among them, the threatened strike of the men, should women ever be introduced into the trade. A strike, however, happened from another cause, about three years ago, and Mr. Douglas, of Bond Street, turned it to a very good use. He took advantage of the opportunity, and at once engaged about a dozen women, and taught them the great art and mystery of hair-cutting! He is perfectly satisfied with the result of his experiment, and so are all his customers, and he has not only increased his own staff, but several London and country establishments are about to follow his example.

Glass-Engraving and Photography

Glass-engraving and photography also afford openings, and “though one swallow does not make a summer,” a woman's capacity in photography can never be disputed after Mrs. Cameron's achievement. The Society for Promoting the Employment of Women has made several successful trials in both directions. The committee state that the progress made by the glass-engraving pupils proves beyond dispute that there is nothing in the work itself which renders it unsuitable to women. All ordinary patterns can now be executed by them; they copy with accuracy, and have engraved glasses of various kinds to match sets, completely to the satisfaction of those [9/10] who have furnished them with this work. At present, one of them is working on monograms, and when she has acquired skill in this branch she will begin to engrave crests. The law-copying office established by this society not only holds its own, but I understand that several women who have been thoroughly trained in it have been drafted off into regular law-stationers’ firms.

Clerical Work

Finding that at least 30,000 men are employed in England in the sale of articles of female attire, and that owing to the ignorance of women in the higher branches of arithmetic, they are unable to obtain employment in this natural direction, the society has also opened a commercial school, in which girls are taught book-keeping, and the committee point with some satisfaction to the fact, that while the census for 1861 returned 274 women as commercial clerks, and 34 as accountants, no return whatever was made under either head before the existence of an organised movement for promoting the industry of educated women.

Pharmaceutical Work

The dispensing of medicine has been tried as a fitting occupation, and is one with which women in olden days were familiar. In a letter I received from Dr. Garrett-Anderson, a fortnight since, in answer to a question I had put to her on this matter, she observes, “There is no reason why women should not be engaged in dispensing, both in charitable institutions, i. shops, and in private practice, as assistants to general medical practi tioners. As a matter of fact, hundreds of women so dispense, in an amateur way, for their husbands or fathers.” She adds:— “We have trained four or five women as dispensers at St. Mary's Dispensary, and we have found them careful and apt pupils, and ready to submit them selves cheerfully to the necessary conditions imposed on them. Our first pupil has held the situation of dispenser for the last four years at a salary of £40 a-year, and she gives me great satisfaction.” I believe that the objections generally raised against the employment of women in this direction chiefly refer to the laborious manipulation with pestle and mortar, the requisite accuracy and exactness for weighing and mixing, or the difficulty an ordinary chemist would experience in receiving women apprentices. It is certainly curious to observe the objections which suggest themselves respecting new employments, which are not even recognised as such under circumstances to which custom has previously reconciled us. Take the last, for example. Girls are continually apprenticed to stationers and drapers, and we all know that measuring ribbons and selling books and envelopes under a master’s eye, and probably with male assistants, can be undertaken without this extraordinary difficulty which a novel proposal encounters. I think that pharmacy is a peculiarly suitable employment for women, and it is by [10/11] no means an untried experiment, for in the last census 388 women were returned as chemists and druggists, and 243 as manufacturing chemists; and though most of these are probably only carrying on the business of a deceased father or husband by means of male assistants, some are, to my own knowledge, conducting the work themselves, and performing the part which usually falls to the head of the establishment.

Finding Fresh Channels

But I have never yet heard of a female tuner of pianofortes, though it has been suggested more than once; and since it was announced that I was to read a paper before your Society, I have received a request from one of your members to mention it on this occasion. I do so gladly, for I think the tuning of pianofortes would prove a very excellent employment, and I specially commend it to your attention. But all such experiments are necessarily limited in their operations, and to find fresh channels for female industry will be a very slow and gradual process. At present, every one who carefully considers this subject, must admit that the contrast is peculiar and striking between the employ ments which are open and the social position of the women most in need of remunerative work. I have not the least patience with that miserable, paltry pride which teaches women to look down upon all paid work, but I have considerable sympathy for those whose sense of the fitness of things is strong enough to induce them to wish their work to correspond in some degree with their education and social position. It is one thing to be impelled by the force of circumstances to take their place in the labour-market, but it is another to find themselves driven into callings which place them on an inferior footing to all their male relations. I know that this part of my subject bristles with real difficulties. It is all very well to suggest that employment such as the Civil Service should be thrown open (and I have often heard this strenuously and generously urged by members of that service), but then what is to become of our young men? I do however venture to think, that as the Government has availed itself of the unpaid services of women, the Educational Department at least ought to acknowledge practically that women are capable of doing official work; and I think that the election of women on our new school boards will be speedily followed by the appointment of women as inspectors of schools.

Anomalous Attitudes of Middle-Class Women

The truth is, that we need to enlarge our views as well as our practice; while we seek to open higher occupations, we must learn to respect work of all kinds more than we do at present. An admirable work has been published by Mr. Milne, of Aberdeen, which could be [11/12] made with great advantage the text-book of this question, in which he shows how, until a comparatively recent period, all men of high degree reaped the fruits of industry in revenues and lordships, themselves remaining an aristocracy — warlike, ecclesiastical, political, and fashionable — according to their age and country, but alike despising industrial occupation, and strangers to its reaction on the character. But, as far as men are concerned, it is very different now; the social importance of industry has become the marked feature of the time. “In our most advanced communities,” says Mr. Milne,

the middle classes have acquired the greatest political weight, and a large measure of personal culture; civilisation is no longer in the keeping of a limited aristocracy; it has permeated the masses, and owes both its recent progress and its future prospects to the elevation of the industrial ranks. Wherever we turn our view, social power and personal culture are found in other hands than once held them.... Our merchants are no longer of a proscribed and despised tribe; our lawyers, our scientific and literary men, no longer exclusively pursue their studies in the leisure hours of a clerical avocation; and our gentlemen are no longer only found in the ranks of a leisured aristocracy.

But with women the case is far otherwise; directly we leave the higher ranks, we find that this great change has produced a division in the minds and characters of the two sexes, as little beneficial to society at large as it is prejudical to the happiness of woman herself. It has produced between the men and women of the middle class an incongruity of taste and a diversity of pursuit. In the higher and lower ranks woman emphatically shares the lot of man, leading with him in the one a life of affluent leisure, and bearing with him in the other a share of the labour characteristic of their common station. But, in the middle class, though man, in his estate, approaches more nearly the lot of the labourer, woman would be an aristocrat; must needs spend her time in visiting or receiving visits, or in equally vain makeshifts to kill time. Like the lady of rank, she is above engaging in industrial pursuits, and she even pities the fate of her sex in the labouring ranks, that woman must share in these the lot of man; but she forgets that for a woman to find happiness in a life of ease, it is requisite that man in the same rank be equally exempt from toil. Unlike the lady of rank, the lady of the middle-classes is left alone during the day. Her husband, father or brother, in place of accompanying her in her visits, or in her other efforts to occupy a day of leisure, is busy at his desk, engrossed in his industrial avocations. Herein lies the drawback at present characteristic of woman's position in the middle ranks. In [12/13] place of conforming to the medium in which her lot is cast, she strains after a false station. Her education, ideas, and manners have reference to a condition different from that she really occupies. She is brought up, and demeans herself, as if she belonged to a different sphere from that of the man in her own rank; and, as a natural consequence, there can be little in common between them; the one trained for industry, the other for a life of fashion; the one for the world, the other for the drawing-room.

A New Role for Middle-Class Women

It has become absolutely necessary that we should learn to value at their proper worth the superficial accomplishments against which we, have railed for some time past, and we really ought to adapt the education and pursuits of women to the sphere in which they are cast. I do not mean that every woman must necessarily participate in some industrial calling, but I think she ought to have some chance given her, besides the chance of finding a husband, in days when it is absolutely necessary to have some other protection, I not only regard it as a matter of vital importance that women should cease to despise industrial occupation, but I think that wherever it is possible they should take their fair share in it. The experience gained would not be thrown away, even in the event of their marriage. I fancy the money expended in such a manner would prove a better dowry than a mere sum paid down on the wedding-day. As things now stand, women are not even trained in domestic economy; they even enter on the one province respecting which there is no dispute, in total ignorance of all its requirements, and many a man’s pocket and temper is overtaxed in consequence. The want of definite training and habits of precision and accuracy is really as disastrous in the household as in the world, and until we secure it little can be done for women who have to work.

The hopeless household management of David Copperfield's child-wife Dora (and his own incompetence too).

We have all heard something of the technical schools which were established some twenty years since in France, and of the system which obtains in Germany; and I believe I am correct in saying that the Society of Arts sent out a number of persons to test the arrangement by which other governments expect to develop the intelligence of their workmen. It is a well-known fact that English artisans have been placed at a disadvantage by the absence of similar institutions here. Mr. Lucraft, in speaking of competition between English and foreign workmen, did not hesitate to say that, owing to advantages obtained by the latter, thanks to the technical schools, which afford preliminary instruction bearing on their future pursuits, Englishmen were “nowhere in the race.” This phrase very aptly describes the present position of women — they are nowhere in the race - and I see every reason for [13/14] attributing this fact to a similar cause. It is not owing to any inherent deficiency, but the utter absence of special training. What was the first effect of the technical education in France? As the men alone received the full advantage of it, the women at once suffered. In 1848, there were 89 designers in Paris. The author of La Pauvre Femme informs us that although there were still designers in 1868, there were no girl apprentices in the trade. In the last census of Paris, the number of women returned as painters on china was 438; in the previous census the number had been above 1,000, and while only 3 apprentices were returned to supply the place af I,OOO workwomen, the boy apprentices numbered 49. We learn from the same source, on the authority of a Paris shopkeeper, that owing to the technical instruction given to the men they far excel the women in dressing the shop windows, and that the want of this training prevents women from harmonizing the colours, from working on canvas, and from embroidering as well as men.

We frequently hear people say, when they wish to depreciate women, that whatever a man undertakes he does better than a woman, from the painting of a picture to the cooking of a dinner. I am quite willing to admit it. But as men have so many advantages, I cannot regard this fact with any very great astonishment, or credit them in consequence with such transcendently superior power. And allowing, with appropriate humility, the utter inferiority of a woman’s capacity, it only strikes me as of still greater importance that we should develop to the utmost any power of which she is possessed. The advantageous effects on men of technical education made themselves so apparent in France that a Paris school for women was established in 1861. This proved so successful that Lyons, Dijon, and other towns followed suit; two schools at least, are due to the Empress Eugenie, who personally attended on more than one occasion, and gave away the prizes to pupils who excelled in works of art. We need such an effort here; it is not sufficient for a few isolated individuals to work in this direction.

The Need for a National Effort

A Society for Promoting the Employment of Women, however admirable, cannot really do what is wanted; a national effort, in the fullest sense of the word, will alone enable us to cope with the difficulties surrounding that large and increasing class of women forced to work, from whom we at present expect bricks though we refuse the straw. It is too late to discuss the question whether women ought to take on themselves the toils of existence, they are doing so already in large numbers, under the compulsion of necessity and under great disadvantages, and the simple fact that they are constantly thrown upon the world to earn their daily bread by their own exertions is a sufficient answer to those who [14/15] think that dependence upon a man is a woman’s proper position. I do not wish to gainsay for one moment those domestic duties which surround the women whose lives have fallen in pleasant places, but I assert from practical experience that thousands of women dare not in these days reckon on the protection and support of a father, husband, or brother, or some one standing in an equivalent position, and I cannot but regard the pretension to decide beforehand what women can or cannot do — when nature will decide it so much better for us by showing us their success or failure — as one of the worst fallacies of the old protective system.

I do not even pretend at this moment to determine what women are likely to do, if they are allowed to do it, for this can only be ascertained by experience, but I do protest against those exclusive customs (founded chiefly on prejudice) which so often exclude women from the higher labour markets without giving them any trial at all. I shall doubtless presently hear, as I have already indicated, that all the trade and professions are overcrowded already, that young men as well as young women are saying "What is that that I should turn to, lighting upon days like these; Every door is barred with gold, and opens but to golden keys." It may be true, that for every clerkship, for example, we find I00 candidates, but I have never yet heard of a class of men, in any rank whatever, compelled to offer their services in return for food and shelter, but you all know women are frequently reduced to this extremity. I constantly receive letters asking me to recommend ladies as companions or governesses, from people who do not scruple to demand the whole of a poor woman’s time, and the possession of a vast number of accomplishments (which ought to have some market value as long as they are indispensable), and in return “a home, and to be treated as one of the family,” is all the remuneration offered. There are plenty of women sufficiently distressed to accept this, and it is not difficult to guess what becomes of them when sickness and old age overtake them. We shall hear, too, that to admit women is to displace men and to reduce their wages, but I think a careful examination of the matter will show, with regard to the latter difficulty, that the real result would be an increase of the productive power of the country, and a slight readjustment of wages. Anyhow, it seems to me that one sex is as much entitled as the other to bread, and that is what wages mean; and many men are already engaged in occupations which seem to me essentially womanly.

Let me give you a few more figures from the census of 1861: [15/16]

Males

- Mercers, drapers, and linen drapers.... 45,660

- Hair dressers and wig makers.... 10,652

- Haberdashers and hosiers.... 4,327

- Straw hat and bonnet makers.... 1,687

- Washermen and laundry keepers.... 1,165

- Stay and corset makers.... 884

- Milliners and dress makers.... 803

- Artificial flower makers.... 761

- Berlin wool dealers.... 63

- Artists in hair, hair workers.... 42

- Baby linen makers.... 13

Total = 66,057

Emigration as a Poor Solution

Still a sad experience: Good-bye to England by Leonard Raven-Hill, on board the S.S. Egypt in 1903.

Other speakers will, perhaps, agree with Mr. W. R. Greg, that the solution of our whole difficulty is to be found in emigration. I am quite ready to assist in any scheme for enabling women to seek in foreign lands the livelihood they cannot obtain in their own, and I think Miss Rye has rendered an immense service to this country by the wise and judicious system she inaugurated, but I really must protest against the idea of enforced transportation in a benevolent disguise. And certainly, before women are fit for colonial hardships, they must have very different views of life and its requirements than they possess at present, and a truer estimate of the value of appearances. But if there be any truth in the much-insisted on argument of the “home sphere,” this notion of wholesale expatriation ought scarcely to receive the support it obtains in some quarters. It is all very well to say that homes will assuredly be offered to them by the adventurous men who have left the old country in the hope of better chances abroad, but the idea of a number of women setting off to the other side of the world with this expectation is far from pleasant. The quieter efforts of young ladies to settle themselves in marriage here deserve and obtain sufficient ridicule and censure to preclude their openly leading such a “forlorn hope,” and if they quit England with any pretext of employment, what becomes of the “home sphere” argument?

"Obliged to Wait"

As far as my experience goes, I have always found that the people who treat the broad question of the employment of women as a revolution for mere “empty rights,” or as an attempt at an “improper insubordination,” are ready enough while neglecting to aid in an effort to deal with a wide-spread distress, to ask our help for special and individual cases in which they are personally concerned. And yet it must be clear to every intelligent person, that all we can do is to call attention to the difficulties by which women are surrounded; we have no chance of giving them employment until the public has been aroused, and ceases [16/17] to view our movement with indifference or dislike. When the facts of the case are really known, I do not hesitate to say that, even if practical help be still withheld, prejudice will be shamed out of active opposition but we shall nevertheless be obliged to wait for hearty co-operation, before we succeed in obtaining for our educated women fair chances of livelihood.

In conclusion, I can only say, that the experience gained from prac tical work, leads me to feel more strongly every day of my life, the necessity of trying to obtain this co-operation as quickly as possible One of the essayists in a book recently published by Macmillan on this subject, did not scruple to say, that she believed “the women of this generation must be content to suffer as victims of a transitional period.” I fear that this view of the case is as correct as it is melancholy, for what can be done with hundreds of women who come to us for employ ment, in the teeth of the two great difficulties which perpetually look us in the face — on the one hand, no openings; on the other no qualifi cations, — owing to the utter want of training? If people wish to save the coming generation from the miseries endured by the present, they must accept this new condition of things and make it a personal matter. But for this hope, all effort would be paralyzed. We work on, conscious, indeed, of the small value of our individual exertions, supported by the firm conviction that when the mists of prejudice are dispersed, and the truth becomes generally known, the public will see the immediate necessity of helping us to solve one of the most painful and delicate problems of the 19th century.

Note at the foot of p.3:

This paper is reprinted from the Arts Journal at the request of many subscribers and though the figures of the Census for 1861 on which many of the arguments rest must now give place to the Census of 1871, the returns are such as to show a still greater increase in the number of women workers. The Spectator of June 24th. observes: "The most melancholy fact in our civilisation, as revealed by the Census, seems to us the disproportion between the sexes. There are in the United Kingdom 913,162 women too many, women who never can by any possibility find husbands at home. This evil is immensely increased by what we believe to be the fact, the existence of the disproportion chiefly in the lower middle-class, and by the semi-feudal basis upon which our society still rests — the law, the etiquette, and the prejudice which assign a monoply of all careers except domestic service, a preferential claim to property, and a preference as to wages to the stronger sex, who also, it is clear, are of the two the more ready to emigrate. There are not enough soldiers and sailors in the kingdom to account for the difference which, therefore, must be created mainly by the difference, in the habit of emigration, whether temporary as to India, or on business, or permanent for settlement. The excessive disparity, we cannot doubt, threatens our civilisation, moral and economical, first, by creating a class retained in celibacy unwillingly and by external force; and secondly, by throwing on the men who, in many classes are alone allowed to work, the burden of a vast army of consumers; and there is, so far as we see, not a chance of any improvement. The tendency of the age is toward international communication, and as the facilities increase, so will they be taken advantage of by men and not by women. As soon as inter-communication is perfect, the disparity may diminish; but it will not altogether disappear, for it exists in an excessive form in the New England States, which are not separated by anything except the railway from the States which attract the emigrant. There is, we believe, no cure except in allowing women to earn money, and educating them until they, like the men, can break loose from the fetters of habit, convention, and that strange instinct which seems to bind so large a section of humanity to the place in which they were born.

Related Material

- Victorian Women's Occupations

- Occupations (male and female): census returns for 1851, 1861 and 1871

- The Figure of the Governess, based on Pearsall's Night's Black Angels

- "On the Side of the Maids" — an 1874 account of a maid's hard life, by Eliza Lynne Linton

Bibliography

Faithfull, Emily. Woman's work: with special reference to industrial employment. London: Victoria Press, 1871. Hathi Trust. Contributed by the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Web. 3 June 2020.

Created 4 June 2020.