Note that there are several portraits in the book, but, apart from the cover scan, the rest of the illustrations here come from the other sources specified. — JB

Through painstaking research on three continents, the authors of this thoroughly readable and informative biography have pulled together a complete account of the life of Margaret Anne Bulkley, whose name was far better known in her own lifetime as Dr James Barry.

Early Life

The authors start by establishing that Bulkley was most likely born in the seaport of Cork, the next largest city to Dublin in Ireland, around 1795 — since records have been destroyed, the precise year of birth cannot be established. But she certainly spent her early years in Cork, where her father, Jeremiah Bulkley, was a grocer and local customs official. Her mother was Mary Anne Bulkley, née Barry. This was an old Catholic family of some standing: Mary Anne’s brother James had established himself as an artist in London, where he was a professor and fellow at the Royal Academy.

However, there were money problems, exacerbated when anti-Catholic feeling after the Act of Union with England in 1801 deprived Jeremiah of his job. He was briefly imprisoned for debt, leaving the young family without support. The Bulkleys had that more dreadful Regency affliction – a profligate son, John, whom the authors describe wryly as "not a reliable young man" (7), and who cost them a great deal of whatever money they managed to get.

Aside from financial difficulties, Margaret Anne is thought to have encountered emotional trauma: Du Preez and Dronfield contend that some time between 1801 and 1803, when she was between the ages of 12 and 14, she was raped, most probably, they believe, by her uncle Redmond Barry. The case is a plausible one, and there is much to suggest that she gave birth to an infant named Juliana, whom Margaret’s parents brought up as their own.

The family was now in desperate circumstances, so much so that their debts drove Mary Anne and Margaret to travel to London to seek help from James Barry. Twice he refused their request; but when he died in 1806, mother and daughter returned to London a third time in order to claim a share of his estate. Margaret was then 17. As a young women with no wealth behind her, she only had one respectable option: to become a governess. Yet she lacked the education needed even for that job. Extra tuition was therefore arranged for her with her uncle’s physician, Dr Fryer, who had been surgeon to George III. It was at this point that a certain General Miranda from Venezuela came into their lives. He painted a vision of a reformed and enlightened society where women would be able to practise medicine.

Mrs Bulkley and Margaret spent a couple of years in London, whilst the former tried to secure her inheritance. Margaret was having tuition to be a governess. In September 1808, Margaret’s brother John wrote to his mother asking her to intervene to stop him being sent in the force that would attack Bonaparte in the Caribbean. Margaret took it upon herself to reply. In her letter, she stated that there was great honour in fighting for king and country and that “Was I not a girl, I would be a soldier!” (qtd. 50). Here was another early indication of her future role.

Setting Out on a Career

Dr Barry as pictured in the Illustrated London News (G.E.C. 448).

Du Preez and Dronfield surmise that the three men who helped shape Margaret’s ambitions to be a doctor were Dr Fryer, Mr Reardon, her mother’s solicitor, and General Miranda. As Du Preez and Dronfield recount the story, “the conspirators were sworn to secrecy” (56). By 1809, Margaret had at last embarked on a journey to Edinburgh to study medicine. This was the point at which she adopted the name James Barry. In Edinburgh, Margaret acquired another, patron, Earl Buchan. There was no entrance examination. Margaret simply paid her fees and enrolled. To her peers, however, she still seemed very young — perhaps around 12 years old — and for someone so young to take the medical examinations was unusual, to say the least. This was a problem which Earl Buchan sorted out for her, and Margaret got her medical degree.

The plan now was for her to go Venezuela and practise medicine there. However, as so often in life, fate intervened. General Miranda went back to his homeland — but he did not receive the warm welcome he had hoped for. The revolution that he wanted did not happen. He ended up back in Spain as a prisoner. Margaret therefore had to re-think her future. She had to find a way to earn a living whether from medicine or something else. She decided on the option of joining the Army as a doctor. Her first step was an apprenticeship with an apothecary at St Thomas’ Hospital in Southwark, and this lasted until 1813. She then applied to be an army doctor, giving her age as 18 when she was in fact 24. Again, she passed the examinations. Fortunately for her, there was no physical test of any kind. As Du Preez and Dronfield note, it would have been impossible for Margaret to have joined the Army Medical Board sixty years later, by which time a thorough head-to-toe examination would have been carried out.

Margaret’s first job as Dr James Barry as an army doctor was at Chelsea Military Hospital. She earned 6s.6d. per day. The army did question her age at this point, but once again, Earl Buchan waded in to help out. Margaret was then sent to Plymouth. Finally, in 1815, she was made an assistant surgeon, and waited for her first posting, As it turned out, this was to Cape Colony.

Overseas Postings

Now firmly in the role of Dr Barry, Margaret arrived in South Africa in October 1816. This was to be her longest and most eventful posting. Armed with a letter from Earl Buchan, she began to mingle in the upper tier of Cape society which revolved around Lord Charles Somerset, the Governor. She was invited to treat the Governor’s wife, and then his daughter, when they fell sick. The Governor’s wife sadly died, but his daughter recovered. The governor was, as might be expected, minded to look favourably on the new, young, talented doctor. She also did good work for the lower tiers of Cape society among prisoners and lepers, ruffling official feathers among the Boer officials as she did so. It was a time of great tension: in 1818, the British were trying to hold the line between the Xhosa and the English and Boer settlers who wanted to expand the colony. Margaret accompanied the governor as he made an official tour through the colony to negotiate with the Xhosa chief. In the same year, the Governor himself became ill and Margaret nursed him back to health. As noted, the Governor had recently been widowed. Du Preez and Downfield speculate that there may have been an affair of some sort between the two of them.

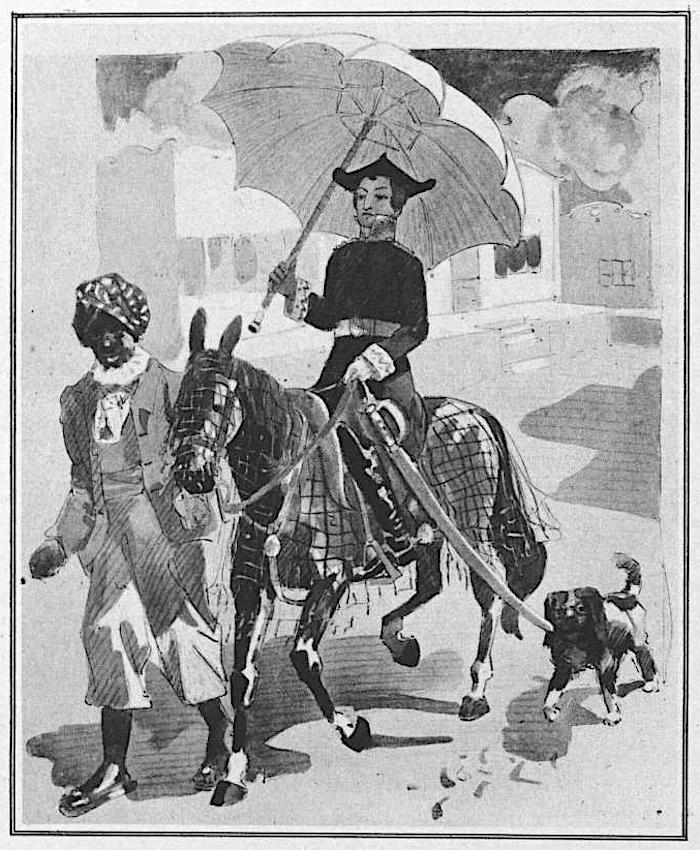

"The Amazing Woman, 'Dr. James Barry,' in Uniform — 'his' pony netted and his negro valet and his dog in attendance"(G.E.C. 448).

The young doctor's time in Cape Colony was eventful in another way: in 1819, she committed a social faux pas and had to accept a challenge to a duel — an instance, the authors suspect, of her overacting "male traits" (445). Luckily, both parties not only survived to tell the tale, but continued to rise in rank. Then in June 1824, Cape Colony was convulsed by reports that Lord Charles had been seen “buggering” Dr Barry — the use of the "coarse" word being taken by the authors to indicate that this was "a genuine witness claim written down verbatim" (185). However, Lord Charles stood by Dr Barry/Margaret and they weathered the storm. Margaret got into various spats with Dutch officials and the Governor generally bailed her out. It is extraordinary that her secret survived in such circumstances.

One of the reasons for her acceptance was undoubtedly her skill. In 1826, for instance, she carried out one of the first caesarean operations in Britain or any of its colonies in which both mother and child survived. The grateful family added the name Barry to their new-born son’s name. South Africa would, in fact, yield the most long-lasting record and oral memory of Margaret’s work as a doctor: she had been in the Cape for over a decade before being ordered to go to Mauritius.

Here, however, she only stayed for a short time. Lord Somerset had been recalled to England to face a commission of enquiry about the governance of the Cape Colony. When Margaret heard that he was ill, she returned to England to nurse him through his final illness. She also found time to write an account of a medical condition which was published in The Lancet. Her adventurous life continued with a posting to Jamaica. During her couple of years there she witnessed the slave rebellion of 1831 and slave emancipation in 1833.

Du Preez and Dronfield have done a phenomenal job of tracing Margaret through the records. However, there is one year, 1835, in which they have been unable to find any record of her. They speculate that she helped her mother get out of the workhouse in Cork and join her son and his wife in England. Then she was on the move again, with a posting to St Helena, where she once again stood up fearlessly for principles, irritating the colonial authorities by demanding more staff and better care for patients. In St Helena, she was court martialled not once but twice. She was cleared after the first court martial but after another contretemps with the colonial and military authorities was sent home to England under arrest. Once there, though, the case against Dr Barry quickly folded.

Her travels now resumed. From 1840, she was posted to various places in the Caribbean and continued to climb up the Army Medical Board hierarchy. In about 1842, a bout of malaria almost led to her exposure: she gave orders that no one in the colonial medical service should visit her, but two army doctors did come when she was very ill, almost delirious. One of them examined her, and discovered that, as he put it, “Barry is a woman!" (294). Margaret woke up, realised what had happened and swore the doctors to secrecy. The secret — and the patient — survived. Having recovered, she continued in that post for another three years, until a bout of yellow fever in 1845 left her seriously debilitated. In October 1845, she sailed for England.

Malta was her next posting. Here, in 1848, she had to deal with a small outbreak of cholera. In 1850 there was a much more severe outbreak which claimed 1,700 lives. Having weathered her exposure to these, she left Malta in April 1855, and was sent next to Corfu, during its brief spell as a British colony. By this time, she was one of the most senior army doctors, and was promoted to the rank of Deputy Inspector General of Hospitals — the rank that would one day be inscribed on her headstone.

Amazingly, the upward trajectory of her career remained unaffected by a number of other instances when observers believed that Dr Barry was female. On one notable occasion, she was in Vienna on holiday when she met the ambassador, Lord Westmorland, his wife, Lady Westmoreland, and his daughter, Lady Rose. Lady Rose wrote an account of meeting Dr Barry with her mother, and noted that Lady Westmorland had said of "him" that “his manner was that of a mincing old maid” (328). Long afterwards, when Lady Rose found out that Dr Barry was indeed female, she came to appreciate that the person she once met had, in fact, been "an adventurous, strong-willed girl" who could never have got into medicine at the time without adopting such “an extreme course"; at this point she recalled too how successfully Margaret had "earned the respect and esteem of her colleagues and superiors" (qtd. 328).

Margaret was back Corfu by 1 April 1853, just as the Crimean War was about to break out. There she was reunited with one of the officers from Jamaica who knew her secret. During the Crimean War, cholera claimed far more lives than the actual fighting. Margaret asked to be deployed to Crimea, and when her request was not granted, took leave of absence to see the situation there for herself. She stayed for three months generally helping out. She had a frosty encounter with Florence Nightingale, who also later found out that Dr Barry was a woman, but who, unlike Lady Rose, did not change her negative view of "him."

In September 1857, Margaret prepared for her final posting, this time to Canada: she was appointed Inspector General of Hospitals, which was then the second highest rank in the Army Medical Department. When she arrived, she found, as so often, colonists of different nationalities at loggerheads with each other; she was soon involved in various personal disputes. Yet, despite being in a certain amount of trouble, she survived in her last role for a number of years. Finally, however, in April 1859, she contracted pneumonia, asked to be relieved of her duties, and sailed for home. As was so often the case in her life, even this return voyage proved eventful. Margaret and her man servant were on one ship, her books and papers on another, and the ship carrying the books and papers was shipwrecked. Inevitably, the lack of written documents has contributed to the challenges of researching her life.

The Last Years and the Aftermath

Her travels were not quite over. Finally free of work responsibilities, Margaret took a holiday to the Caribbean. She went out with her menagerie of animals, and John her manservant; the two were photographed together there. In Barbados, Margaret met Captain Cloete – the man she had had a duel with in South Africa. By now, he had become a Major General and been knighted. But these were her last encounters abroad with people from her colorful past. On returning to England, she stayed in lodgings at 14 Margaret Street, very close to where her uncle, the distinguished artist James Barry, lived in Little Castle Street. She was now entering her final illness, and called her friend, Dr Reid McKinnon, whom she knew from the Caribbean to treat her. Apparently, he did not discover her secret. She died, her identity as Dr Barry intact, on 24 July 1865.

Barry's headstone in Kensal Green Cemetery (author's photo).

Of course, that was not the end of the story. The maid of all work at the lodging house, Sophia Bishop, went to find Dr McKinnon who certified the cause of death. He saw no need to examine the body. Next came the “layer-out,” the woman who had the job of actually looking at the body and getting it ready for undertakers. The following day, 26 July, Dr McKinnon and Sophia went to the Marylebone Register Office to formally register the death. The funeral went ahead and the grave stone was put up. But the layer-out had not been paid for her work, and was aggrieved. Dr McKinnon was summoned to the office of Margaret’s agent, who was handling her estate, and in the process of demanding her money, the layer-out dropped as an aside that Dr Barry was female. Dr McKinnon said he was not aware of this. “'Well, a pretty doctor you must be not to know that!” she said, 'I wouldn't like to be attended by you'!!" (qtd. 378). Dr McKinnon then said Dr Barry might be an improperly developed man or a hermaphrodite, to which the layer-out retorted that the body was that of a “perfect female” who had had a child "when very young" (qtd. 379, corroborating the childhood rape incident). When McKinnon still brushed her off, the layer-out had every incentive to tell her story to anyone who would listen. It was not long before the army heard about it. The story broke publicly first in Ireland, then in England and then finally across the whole Empire. As the authors point out, it inspired various retellings, starting as early as 1867 with Charles Dickens's "Doctor Barry" in All the Year Round, and this biography will help to ensure that it still fascinates us today.

While Dupreez and Dronfield's step-by-step account of the life of Margaret Bulkley is not aimed at an exclusively academic readership, it has all the requisite scholarly apparatus and is surely the definitive work on this subject: it explains the why and the how of their subject's life working as an army doctor for some 40 years, with research fully supported by some 70 pages of notes and primary sources. It is worth mentioning that it also includes two appendices, the first going into more detail about the later requirement for army doctors to undergo a physical examination; the second, explaining in detail that it was not the lodging house's Sophia Bishop but the layer-out who discovered her secret. The latter, incidentally, is compared to the fictional Mrs Gamp in Martin Chuzzlewit.

The story is indeed an amazing one. As Dr Barry, Margaret had had great success in a life that she could never have imagined when she set off for medical training in Edinburgh. But there had been signs of "stress, frustration and outbursts of rage" (154), and there was undoubtedly an element of sacrifice involved. As a poignant footnote to her story, we learn that she had kept a battered old trunk with her at all times throughout her career. Many years after the shipwreck that destroyed her other possessions and papers, the trunk that had successfully travelled with her to England was opened. The lid was found to be covered with a collage of pictures of women’s dresses: "fashion plates clipped from ladies’ magazines — a parade of gowns, crinolines, bonnets, hats and coiffures pasted to the musty leather: a catalogue of loss and longing" (382).

Bibliography

Du Preez, Michael, and Jeremy Dronfield. Dr James Barry, A Woman Ahead of Her Time. One World Publishing: London, 2016. 479 pp.

[Illustration source] G.E.C. "An Amazing Male Impersonation: The Strange Story of James Barry Esq., MD." Illustrated London News 16 March 1929. Internet Archive. 4 June 2025.

Created 5 June 2025

Last modified 20 June 2025