[This document comes from Helena Wojtczak's English Social History: Women of Nineteenth-Century Hastings and St.Leonards. An Illustrated Historical Miscellany, which the author has graciously shared with readers of the Victorian Web. Click on the title to obtain the original site, which has additional information.]

Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon (1827-91) was one of the foremost founders of the women's rights movement in Britain. She was born in Whatlington, near Battle, Sussex, died at nearby Robertsbridge, and was connected to the Hastings area throughout her life.

Family Background

Barbara's father, Benjamin Leigh Smith, was an MP's only son. He had four sisters. One married into the Nightingale family and produced a daughter, Florence; another married into the Bonham-Carter family. Smith's home was 5 Blandford Square, Marylebone, London, but from 1816 he inherited and purchased property near Hastings: Brown's Farm near Robertsbridge, with a house built around 1700 (extant), and Crowham Manor, Westfield, which included 200 acres. although a member of the landed gentry, Smith held radical views. He was a Dissenter, a Unitarian, a supporter of Free Trade, and a benefactor to the poor. In 1826 he bore the cost of building a school for the inner city poor at Vincent Square, Westminster, and paid a penny a week towards the fees for each child, the same amount as paid by their parents.

Ben's father wanted him to marry Mary Shore, the sister of William Nightingale, an in law by marriage; however, on a visit to his sister in Derbyshire in 1826 Smith met Anne Longden, a 25-year-old milliner from Alfreton. She became pregnant and Smith took her to a rented lodge at Whatlington, a small village in Sussex. There she lived as 'Mrs Leigh', the surname of Ben Smith's relations on the Isle of Wight. The child, Barbara, was born on 8 April 1827. Smith rode on horseback from Brown's Farm to visit them daily, and within eight weeks Anne was pregnant again.

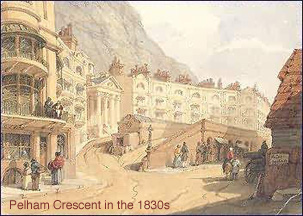

When little Ben was born the four of them went to America for two years, during which time another child was conceived. On their return to Sussex they lived openly together at Brown's (left), and had two more children. After their last child was born, in 1833, Anne became ill and Smith leased 9 Pelham Crescent, which faced the sea at Hastings; the healthy properties of sea air were highly regarded at the time. A local woman, Hannah Walker, was employed to look after the children. Anne did not recover so Smith took her to Ryde, Isle of Wight, where she died in 1834.

It is something of a mystery that the couple never wed. The scandal of marrying a woman from a lower social class was nothing compared with raising five children out of wedlock. Biographer Pam Hirsch feels that perhaps Smith did not want Anne and the children to become his chattels, as the law would have deemed them had the pair married. This would certainly have fitted in with Smith's radical beliefs and later actions.

In 1836, when Barbara was nine, Smith and the five children settled permanently into 9 Pelham Crescent (right). Smith was elected MP for Norwich and while at the House of Commons, he asked Aunt Dolly Longden or Aunt Julia Smith to look after the children. Local people were employed to help: Catherine Spooner, governess; Harry Porter, Latin and history tutor; and Mr Willetts, the foremost local riding master. In 1842 Smith spent £215 on a beautifully ornate, eight-seater omnibus from the best coachbuilders in Hastings, Rock and Baxter of 6 Stratford Place, West Parade. With coachman Stephen Elliott at the reins, four horses drew the magnificent vehicle carrying the Leigh Smith children and their staff around Sussex and the home counties.

During the 1840s Benjamin Smith bought more land to the south and west of Robertsbridge, including Scalands Farm (extant), Mountfield Park Farm (extant) and Glottenham Manor (rebuilt and now a nursing home). The latter included the ruins of a 14th-century fortified and moated house. When each of his children reached 21, Smith broke with tradition and custom by treating his daughters the same as his sons, giving them investments which brought each an annual income of £300. He also gave to Barbara the deeds of the Westminster school.

Bodichon's Unconventional Upbringing

The combination of an unconventional upbringing and a private income placed Barbara in an extraordinary position for a mid-Victorian woman. Whereas most women were raised to be obedient and expected only to marry, bear children and live in subordination to a husband, Barbara was free to live her life almost as she pleased. Money could not buy everything, however; for example her brother Ben went to Jesus College Cambridge in 1848, but Barbara was denied such academic opportunities, since no university would admit women. But she did not succomb to housewifery; she became a painter and social reformer. Despite her wealth Barbara eschewed high society and allied herself with the bohemian, the artistic, and the downtrodden.

Despite having illegitimate children, Benjamin Smith was highly regarded and he became a magistrate in Hastings in 1845 after retiring from Parliament. His children were accepted by Hastings society and during her seventeen years at Pelham Crescent Barbara became acquainted with many notable people. In 1846 she met her best friend Bessie Rayner Parkes (right), when Bessie's father hired rooms from Smith at 6 Pelham Crescent. In Hastings Barbara also met Anna Howitt and her children; Eliza Fox Bridell; Gertrude Jekyll; Marianne North, whose father was one of the two Hastings' MPs; Miss Bayley of 2 Holloway Place; and Ann Samworth and her children, who lived at Brooklands Cottage, Holloway place, Old London road.

Life in the Art World

The three Samworth girls and the three Leigh Smith girls enjoyed painting expeditions around Hastings. Barbara studied art at Bedford Square Ladies College (London) during 1849 and gained some reknown as a painter. Some of her work is held at Hastings Museum; other paintings are at Girton College, Cambridge. The Hastings & St Leonards Observer wrote (in 1891) of her paintings:

Among the canvasses the scenes of Algerian landscapes are such that only a born artist would dare to paint. The most vivid colours are dashed about in wonderful profusion, and such a critic as Ruskin has spoken in terms of high praise of her clever work.

In the art world Barbara met the painter William Hunt, who lived during the winter in a small house at the foot of the East Cliff, Hastings. Barbara's painting tutors included W. Collingwood Smith, who took her to meet John Hornby Maw in West Hill House. Through Miss Bayley she met George Scharf, later director of the National Portrait Gallery. Through the Howitts she met Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Anna Jameson, Adelaide Procter and William Johnson Fox, the Unitarian minister. In 1852 she met George Eliot, who was to remain a lifelong friend.

As well as art, Barbara studied political economy and law at Bedford Square. Another lifelong friend was William Ransom (b.1822), a printer and stationer based at 42 George Street, Hastings. He gave her the opportunity to get her radical ideas into print by allowing her to write women's emancipation articles for his newspaper, the Hastings & St Leonards News. From June to August 1848 Barbara wrote, under the pen-name "Esculapius," An Appeal to the Inhabitants of Hastings, Conformity to Custom and The Education of Women.

In 1850 Bessie Parkes introduced Barbara to her cousin, the first woman physician, Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell. However, Barbara's cousin Florence Nightingale snubbed her Uncle Ben's illegitimate offspring.

As young women of 21 and 23, Bessie and Barbara were, most unusually, allowed to go unchaperoned on a walking tour of Belgium, Germany, Switzerland, Austria, visiting Mary Howitt in Munich. The three discussed women's inferior status and wanted to change it. But men held all political power and would fight to preserve the system which served their interests so well. The two did, however, indulge in a little personal liberation. Female costume at the time was uncomfortable, impractical and restrictive. They abandoned their corsets and shortened their skirts, prompting Barbara to pen the lines:

Oh! Isn't it jolly

To cast away folly

And cut all one's clothes a peg shorter

(A good many pegs)

And rejoice in one's legs

Like a free-minded Albion's daughter.

They were also, rather audaciously, swanning around in heavy boots and wearing blue tinted spectacles!

From the early 1850s Barbara divided her life between Hastings and London. The opening of the railway line to London in 1851 shortened her journeys to just 2 1/2 hours. Prior to this, the journey took 8 hours, either by road, or by road and rail via Staplehurst Station.

Willie Leigh Smith became estates manager at Glottenham and Ben was training to be a barrister so in 1853 their father gave up Pelham Crescent. Smith and Barbara lived at Blandford Square or in Sussex, staying often at Scalands Farm. While in the Hastings area Barbara continued to spend time among artists and bohemians. Among her friends were members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood including Rossetti and Siddal. It was she who arranged convalescent accommodation for Lizzie Siddal at 5 High Street in 1854.

The Battle for Women's Suffrage

In London Barbara met the Americans, Elizabeth Stanton and Lucretia Mott, and Harriet Martineau and Mary Somerville, all now famous for their feminist activism. In 1854 Barbara wrote her first nation-wide publication, A Brief Summary, in Plain Language, of the Most Important Laws concerning Women. This remarkable document listed for the first time the legal disabilities and restrictions under which women lived. Barbara proved herself a researcher and scholar by sifting through all the laws of Britain to create 'a pamphlet very thin and insignificant looking, but destined to be the small end of the wedge which was to change the whole fabric of the law' [Englishwoman's Review, 1891, p. 149.] It was widely read and discussed and provided an agenda for action. Barbara's friends and fellow feminists Florence and Rosamund Davenport Hill discussed the pamphlet with their solicitor brother Alfred, who took it to the Law Amendment Society, of which he was a member, which appointed a committee to investigate the laws listed.

As Barbara may have been aware, women's suffrage had already been taken up in a very small way by Anne Knight (1786-1862), who had founded a Female Political Association in 1847 to demand votes for women, and petitioned parliament; and also by Harriet Taylor Mill (1807-1858), who in 1851 argued for women's suffrage in the Westminster Review, a paper edited by her husband, John Stuart Mill. Barbara's priority however was to tackle women's non-existence within marriage. When a woman married, everything she owned, inherited or earned belonged solely to her husband to dispose of as he wished (see my brief overview of women's status). This arrangement was long standing and was rarely questioned. At the time, to even contemplate changing it seemed outlandish; yet Barbara formed a committee whose intention was to reform the law and give married women rights to their own property. Many men said it would cause arguments between married couples; others said that the move would upset the "natural" balance of power between husbands and wives; some feared that women would become self-assertive, a fearful prospect for men.

Within a year Barbara's little committee had become a nation-wide campaign group, and she drafted a petition, the text of which was published in the Hastings and St Leonards News on 15th February 1856. A footnote informed the reader that one of the 70 copies of the petition was lying at Mr Winter's shop at 59 George Street, Hastings (pictured).

The paper had "no doubt that many ladies will find their way thither to attach their names." The committee also compiled case studies of how individual women were suffering because of the law. There were hundreds of instances of women losing everything on marrying a man who absconded after the wedding, leaving them destitute. If such a woman was subsequently to earn or inherit any money, the errant husband could return at any time, seize all she had and leave once more. The petition was intended to support the suggestions of the Law Amendment Society.

The 70 parts were pasted together and presented to the House of Lords in March 1856 with 26,000 signatures. This was the first organised feminist action in the UK.Its rejection comes as no surprise given that Parliament consisted of men, most of whom were married and therefore benefited directly from the status quo. However, the ladies did not give up and, after much discussion, in 1857 the Married Women's Property Bill passed its first and second readings in the House of Commons.

Barbara's personal qualities were lauded in her day and after. Bessie described Barbara as "the most powerful woman I have ever known." Dale Spender points out that Barbara is "almost invariably portrayed... as a woman of glowing strength, active intelligence, warmth, understanding, and energy". Barbara's friend Jessie Boucherett described her as "beautifully dressed, of radiant beauty, and with masses of golden hair", and historian Ray Strachey remarked:

There seems to have been something particularly vigorous about Barbara Leigh Smith, who was taken by George Eliot as the model for Romola [the eponymous heroine of a novel]. Tall, handsome, generous and quite unselfconscious, she swept along, distracted only by the too great abundance of her interests and talents, and the too great outflowing of her sympathies... Life was a stirring affair for Barbara. Everything was before her -- Art (for her painting was taken seriously by many eminent painters), philanthropy, education, politics -- everything lay at her feet. The only trouble was to pick and choose.

Another of her interests was spiritualism: she attended a series of séances in London during 1853 with Rossetti, Bessie, and the Howitts. Stress and overexhaustion led to a serious nervous collapse in 1856 on returning from a trip to Rome.

Just prior to this breakdown, Barbara had a love afair with her publisher John Chapman, who was married. He was by all accounts a philanderer and rogue who Barbara's father wanted her to shun. Ben Smith arranged trip to Algeria with her brother Ben and their sisters. There she met Eugène Bodichon, a French physician, who she married on 2 July 1857. Most unusually for a woman at that time, she wrote her profession on her marriage certificate ("artist"). Eugène was as unconventional and free-thinking as Barbara: for much of their marriage she spent half the year with him in Algeria and the remainder without him in England, where she continued her profession and her feminist campaigning. During their seven-month honeymoon they visited Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell in the USA and Barbara entreated her to return to England. The following year Dr. Blackwell was a guest at Barbara's London home. Barbara introduced her to Elizabeth Garrett, an aspiring physician. This meeting was to prove a momentous one, for the two later opened the first women's medical practices in London. (Garrett later became famous and London's Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital was named for her.) Under Barbara's influence, in 1879, Blackwell moved to Hastings, where she remained until her death 30 years later.

In 1857 Barbara published a very radical pamphlet called Women and Work in which she asserted: "No human being has the right to be idle... Women must, as children of God, be trained to do some work in the world." She called for equality of education and work opportunities and advocated that all married women should work, citing nature as support: "Birds, both cock and hen, help one another to build their nest" Again, this was an outrageous demand, and thought by some to be subversive. Barbara did not hold back; she said plainly that letting men hold all the financial resources of the world and then refusing to admit women to any decently-paid work or professional career forced them to marry for financial support, which amounted to legal prostitution; and the 43 percent of women with no man to support them lived in poverty which led many to succumb to casual prostitution. Barbara made plain that she meant interesting, challenging occupations and not menial or domestic chores by emphasising that women needed: "WORK - not drudgery, but WORK". In 1858 Barbara purchased The Englishwoman's Journal and was able to disseminate her ideas more widely. It was published nation-wide and informed women about the rights movement. From this sprung the Association for Promoting the Employment of Women.

Between 1853 and 1863, Barbara was a frequent visitor to the Hastings area, staying on the family estates, or back at No. 9 Pelham Crescent, where her sister's family now leased rooms, or with the Samworths at Hastings. She painted Mrs Samworth's corn field in 1855, near the spot where another of the Samworth's house-guests, Holman Hunt, had painted Our English Coasts three years earlier.

When Smith died in 1860 Barbara inherited 5 Blandford Square, Ben inherited the Glottenham estates and Willie inherited Crowham Manor. In 1863 Barbara leased three acres from Ben and built Scalands Cottage in a pinewood clearing in Harding's Wood. It was near Scaland's Farm but closer to the road, and thus she called it Scalands Gate (extant, now Scaland's Folly). The house was built to Barbara's own design and specification. The internal walls were covered from floor to ceiling with Barbara's own paintings. Gertrude Jekyll created the garden. The house was visited by Barbara's interesting circle of friends. In the 1860s these included Mary Howitt, Rossetti and Siddal, Frederick and Marianne North, Dean and Lady Stanley, and Herbert Gladstone (who became Prime Minister). Later guests included the Brownings, Gertrude Martineau, Lord Brassey, Henry Fawett, George Eliot and John Ruskin.

Miss Davies and Miss Garrett present the petition to John Stuart Mill.

In 1865 Barbara, as a member of the Kensington Society, co-drafted another petition, this time for women's suffrage. Two women took it to Westminster Hall: Elizabeth Garrett and Emily Davies, (with whom Barbara founded Girton College). Feeling self-conscious, they asked the apple-seller to hide the huge petition under her stall while they waited for John Stuart Mill MP. She agreed, but bid the ladies unroll it a little so that she could apppend her own signature. Mill accepted the petition (pictured) and presented it to the House of Commons in 1866 to support an amendment to the Reform Act that would give women the vote. It was defeated by 196 votes to 73. In 1869 Barbara contributed to the debate once again by publishing Reasons for and against the Enfranchisement of Women and J.S. Mill published The Subjection of Women.

Barbara's life in the world away from Hastings was extraordinarily varied, busy and productive. Her story has been admirably documented by her biographers and will not, therefore, be repeated here. Pam Hirsch's 1998 work is highly reccommended. There is also a 1949 biography by Hester Burton.

Later Years

Instead we jump forward to 1882 and find Barbara bestowing her philanthropy increasingly on her local area, in particular she funded Scalands Night School for the poor.

Barbara had hoped to have children, but this was not to be. After 28 years of marriage Eugène died in 1885 and shortly afterwards Barbara suffered a stroke at her cottage at Zennor, Cornwall, after which she was an invalid. In her declining years, Barbara specified that Mr E. Taught of Castle Road, Hastings was to undertake her funeral and chose a quiet spot in a country churchyward in which she wished to be buried.

When she died, in June 1891, the Hastings & St Leonards Observer wrote that

a movement started by her culminated in the Married Women's Property Act, and with a little help from Miss Davies she founded Girton College. There is one other act that the deceased lady did, for which the world is indebted to her, and that was to bring before the world the writings of "George Eliot".

Strangely, since then, Barbara's achievements have been submerged and, until recently, almost forgotten. She is not nearly as famous as some of her contemporaries who achieved less.

The funeral procession route was lined with hundreds of people whom she had helped to educate at the night school. The Hastings & St Leonards Observer wrote:

Those who were present will never forget the sight so long as they live... From the house to the grave side sad faces and tear-rimmed eyes filled the roads... [Inside the church were heard] sobs that would not be stifled... She gave with a free hand, and left before the recipient had time to thank her... She was a true Englishwoman, of noble character, strong in purpose, and quick to act on any sensible suggestion, if someone would be blessed by it.

In another article the newspaper remarked that:

The deceased lady was a militant Radical, but she lived only to do good. The poor of Scalands Gate have sustained the loss of a warm sympathiser... she housed and educated her labourers and their families... Madame was accustomed to receive the visits of politicians, authors, artists, and others of name and fame in the great world... But upon none can have grief for her departure come more acutely than upon Mr William Ransom and Miss Sanderson, both old, admiring and attached friends... Her whole life was wrapped up in trying to elevate the poor, and alleviate the sufferings of all that were downtrodden.

Barbara was buried at St Thomas à Becket Church, Brightling. The inscription on her gravestone is now almost indecipherable. Her name is absent from the church guidebook's list of the notable people buried there.

Her brother Ben is thought worthy of inclusion, as he was an Arctic explorer. Readers may ponder why this is considered worthy of note while founding the British women's rights movement in Britain is not. There was not even a Blue Plaque on No. 9 Pelham Cresent. This was rectified in April 2000, at my request, by Hastings Borough Council -- 109 years after Barbara's death. Scalands was partly destroyed by fire in the 1950s. It was rebuilt on the same site and still stands, as Scaland's Folly.

Related Material

Bibliography

Spender, Dale. Women of Ideas. Pandora, 1982.

Strachey, Ray. The Cause Bell & Son, 1928.

Last modified 5 April 2021