Want to know how to navigate the Victorian Web? Click here.

Flaubert sacrificed propriety to truth, and Miss Braddon has sacrificed truth to propriety. . . . There is a school of English writers who seem to consider that the one fault their heroines may not commit is a breach of positive chastity. If these writers had to emendate the gospels, they would take especial care to inform us that the woman taken in adultery had been guilty of bigamy believing her just husband to be dead, and that the Magdalene had been seduced under the pretext of a fictitious marriage. — 1864 review of Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s The Doctor’s Wife

The whole object of these books is to take their readers into an imaginary world. For our own part, we think that the object is not only unobjectionable, but praiseworthy. The instinct of poetry which exists in every human breast indicates itself in this love of poor readers for stories of lords and ladies and palatial mansions and sparkling coronets and wild adventure — for descriptions, in fact, of a life far other from that in which those who read them have been born and bred and have to die. It is all very well to say that people ought to be contented with their lot, and that happiness, on the whole, is equally apportioned to every class; but the time will never come when people will learn to believe that flat beer is as nice a beverage as champagne, or that an attic in St. Giles's is as comfortable as a first floor in Belgravia. If every sensational romance could be suppressed to-morrow, the working classes would not become at once converted to the creed that everything was the best for them in the bost possible of worlds. — 1864 essay in The Reader

Several mid-century phenomena led to the popularity of the Sensation Novel:

- the abolition of the stamp duty on printing paper in 1855

- the concomitant increase in the circulation of newspapers

- an increase in numbers of readers in mid-Victorian Britain

- the dramatic increase in the number of circulating libraries

- new weekly and monthly (often illustrated) literary magazines

- high-interest, serialised fiction to maintain a stable readership

- notorious trials such as that of the poisoner Palmer

- tabloid journalism

- reforms in divorce procedures

- public education

Thus, writing in 1863, H. L. Mansel castigated the new subgenre as "preaching to the nerves instead of the judgment" (357). Since early in his anti-Sensation diatribe Mansel refers to "A pale young lady in a white dress" (358), we can be certain that his chief target is Wilkie Collins, whose The Woman in White (1860) initiated the Sensation mania. The typical practitioner of the new form, contended Mansel, aims at creating excitement alone in order "to supply the cravings of a diseased appetite" (357) prevalent in the recently augmented reading public: "No divine influence can be imagined as presiding over the birth of his work; no more immortality is dreamed of for it than for the fashions of the current season. A commercial atmosphere floats around works of this class, redolent of the manufactory and the shop" [357].

Although Wilkie Collins may well have been "The King of Sensation," the royal family of this new subgenre was by no means small, the most popular writers including

[••• =no material on this site. Clicking on other authors will bring you to their homepages.]

- William Black•••

- Mary Elizabeth (M. E.) Braddon ("The Queen of the Circulating Libraries")

- Henry Kingsley

- Ouida (Marie Louise de la Ramée;)

- James Payn•••

- Charles Reade

- George William MacArthur Reynolds (the most widely read Victorian novelist)

- Ellen Price (Mrs. Henry Wood)

- Edmund Yates•••

Although the form is often spoken of as a phenomenon of two decades, its influences may well be detected in works written after 1880, including the novels of Thomas Hardy (whose first effort, Desperate Remedies is very much in the Sensation vein), George Moore, Robert Louis Stevenson, and George Du Maurier, whose diabolical Svengali in Trilby (1896) is very much a Collinsian villain, except for his lack of gentlemanly status.

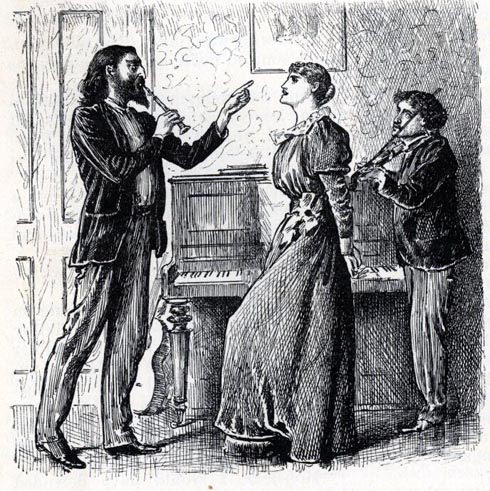

Two of Du Maurier's illustrations for his own novel Trilby.

[Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Ira B. Nadel in the Dictionary of Literary Biography, Volume 18, has attributed the success of Collins among a crowded field of practitioners of the new form to his "expert plotting with carefully described settings" (62), so evident in the novel that appears to initiated the public's mania for Sensation Novels, The Woman in White (1860). T. S. Eliot and Dorothy L. Sayers regard Collins's second best-seller in the genre, The Moonstone (1868), as the first detective novel in English, although Edgar Allen Poe initiated the crime-and-detection story two decades earlier. Whether one is considering Ellen Price Wood's East Lynne (1861) or M. E. Braddon's Lady Audley's Secret (1862) or Collins's early Sensation Novels, one will find the pattern of "criminality and passion beneath respectable surfaces" (Kalikoff 120); often, the Sensation Novel features a beautiful, clever young woman who, like Magdalen Vanstone in Collins's No Name (1862), is adept at disguise and deception —such women are doubly dangerous and generate social instability because they possess and threaten to use secret knowledge. Other strategies employed by Sensation authors include the exposure of hypocrisy in polite society, intentional and unintentional bigamy, adultery, hidden illegitimacy, extreme emotionalism, melodramatic dialogue and plotting, and the brilliant but eccentric villain with gentlemanly pretensions. Reginald C. Terry in Victorian Popular Fiction, 1860-80 employs the term "detailism" to describe yet another aspect of the Sensation Novel, its rigorous realism that catered to a contemporary "taste for the factual" (55) in its descriptions and settings, a feature that novelists such as Collins skillfully blended with the exciting "ingredients of suspense, melodrama and extremes of behaviour" (55). In addition, Terry notes how the plots of such novels often utilized "the apparatus of ruined heiresses, impossible wills, damning letters, skeletons in cupboards, [and] misappropriated legacies" (74). P. D. Edwards adds yet further "ingredients" to the Sensation formula: "arson, blackmail, madness, and persecuted innocence (usually young and female), acted out in the most ordinary and respectable social settings and narrated with ostentatious care for factual accuracy and fulness of circumstantial detail" (703). To all of these features we should add the realistic and sympathetic investigation of individual psychology and an exploration of the female psyche in the manner of George Eliot and Charlotte Brontë. The prevalence of these "ingredients" in the popular fiction of the 1860s and 1870s suggests that the Sensation Novel drew its energy from a popular mid-Victorian reaction to middle-class stodginess and prudery, a reaction that continued well past 1880 and is evident in such late Victorian works as Du Maurier's Trilby (1894) (whose arch-villain, Svengali, is reminiscent of the highly manipulative criminal master-minds of Collins, but lacks their breeding) and Stevenson's Dr. Jeckyll and Mr. Hyde (1886).

P. D. Edwards notes that the term "Sensation Novel" was originally applied disparagingly to a broad range of crime, mystery, and horror novels written in the early 1860s, noting that: "A writer in the Literary Budget, November 1861, asserted that the term originated in America" (1860). The subgenre was effectively defined in a two-year period by the novels of Wilkie Collins, Ellen Price Wood, and Mary Elizabeth Braddon, first serialised in the new literary magazines before appearing in the triple-decker format favoured by the lending-libraries. Reginald C. Terry in Victorian Popular Fiction, 1860-80 contends that B. F. Fisher's, in the 16 February 1861 number of the London Review, is the earliest reference to "sensation novelists" in a discussion of a current trend in American literature, "although in a general way 'sensation' had been applied to Wilkie Collins in 1855 reviews of Antonia and Basil" (181).

The question of identity is integral to this [The Woman in White] as to other sensation fictions. Mistaken identity, hidden identities, are the staple of Collins's No Name (1862) and Armadale (1866), and Mary Braddon's Lady Audley's Secret (1862), and are often concerned with questions of inheritance, with legal identity, but the language of psychology allowed other dimensions of the question to be addressed. What precisely constitutes identity comes into question as the workings of memory are investigated, and found to be lacking [in The Moonstone (1868)]. [Marshall, "Psychology and the sensation novel," 58-59]

Features commonly associated with the publishing phenomenon of the 1860s known as the Sensation Novel include the following:

- bigamous marriages

- misdirected letters

- romantic triangles

- heroines placed in physical danger

- drugs, potions, and/or poisons

- characters adopt disguises

- trained coincidences

- aristocratic villains

- heightened suspense detailism

In 1863 Punch parodied these characteristic features of the Sensation novels in a mock advertisement for The Sensation Times, and Chronicle of Excitement, which informed prospective readers that “this Journal will be devoted chiefly to the following objects; namely, Harrowing the Mind, Making the Flesh Creep, Causing the Hair to Stand on End, Giving Shocks to the Nervous System, Destroying Conventional Moralities, and generally Unfitting the Public for the Prosaic Avocations of Life” (cited in Hughes 3). The parodist promises the public graphic accounts of violent crimes, corporal punishments, and animal cruelty, as well as a Sensation Novel (presumably in serial) full of "hitherto undreamed of" atrocities and written by an "eminent" writer shortly to be released from a penitentiary. The novels that are the subject of this lampoon are not immediately obvious, but were undoubtedly all available for a modest annual "lending" fee at Mudie's Library or in the bookstalls of most railway stations.

In The Maniac in the Cellar (1980), Winifred Hughes associates the rise of the Sensation Novel in the early 1860s with the continued popular taste for the Gothic Novel of the previous century (particularly the goosebump gothicism of Ann Radcliffe and the more gruesome gothicism of Matthew G. "Monk" Lewis, the historical romances of Sir Walter Scott, the oriental tales of Lord Byron) and the more recent Newgate Novel, as pioneered by Harrison Ainsworth, Edward G. D. Bulwer-Lytton, and Charles Dickens. Conservative critics, she contends, regarded this new subgenre, as exemplified by the early '60s novels of Wilkie Collins, Ellen Price Wood, and M. E. Braddon, as "brash, vulgar, and subversive" (6). In his autobiography, novelist Anthony Trollope went so far as to label the Sensation Novel "unrealistic" by the mid-1870s in that he held "The novelists who are considered to be anti-sensational are generally called realistic" (1883: Vol. 2, p. 41; cited in Hughes, p. 39). He might well have added "dramatic," "theatrical," or "melodramatic" to his indictment since a number of Sensation writers acted and wrote for the stage, and since novels such as East Lynne and Lady Audley's Secret proved popular with audiences when adapted for the theatre.

According to Hughes, "what distinguishes the true sensation genre as it appeared in its prime during the 1860s is the violent yoking of romance and realism, traditionally the two contradictory modes of literary perception" (16). If we take the early novels of Collins as our locus classicus, we can see that the new subgenre indeed fused opposites, both possible and improbable, solidly English and yet exotic, sordid and yet respectable, refined yet violent, scientific and yet superstitious, documentary and yet far-fetched, realistic and yet romantic, rational and at the same time absurdist, but above all romantic and suspenseful, "a kind of civilized melodrama, modernized and domesticated — not only an everyday gothic, minus the supernatural and aristocratic trappings, but also a middle-class Newgate, featuring spectacular crime unconnected with the usual criminal classes. (Hughes 16)

George Augustus Sala in "On the 'Sensational' in Literature and Art" (Belgravia 4 [1868]: 455), undoubtedly trying to legitimize the extreme form that had recently appeared, attributed the founding of the Sensation Novel to no less a figure than Charles Dickens. Although some of Dickens's later works, especially The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870), exhibit some of the tendencies of Sensation fiction, in his last novel he was more likely responding to the new form, as produced by his apprentice and associate at All the Year Round, Wilkie Collins, rather than merely aping it. Collins and Reade, however, may have borrowed their aesthetic theory from Dickens, dwelling, as Bleak House remarks, upon "the romantic side of familiar things." A holdover from an earlier generation of writers, Dickens so strenuously objected to the explicit sexuality and social radicalism of Charles Reade's Very Hard Cash (1863) that he adopted the (for him) unusual expedient of publishing a disclaimer at the conclusion of the novel's final instalment in All the Year Round. Lillian Nayder estimates that Dickens was correct in assuming that Reade's candour lost him readers "in droves" (Pilgrim Letters 10: 237), "perhaps as many as three thousand" (Nayder 137). Whereas, moreover, in Dickens, plot —no matter how convoluted or complicated — and character — no matter how eccentric or whimsical — are always enlisted in the service of theme, in much Sensation fiction plot and incident —rendered complicated for their own sakes — predominate because the writer's chief intention is to delight and horrify rather than to instruct and reform. Typically, no sooner has a Sensation writer solved one mystery or resolved one dilemma for us than he or she must introduce another in order to escalate suspense. "The difficulty with this [pattern], of course, is that climax becomes the routine, subjecting the reader to an endless roller-coaster effect that eventually loses its thrill" (Hughes 19).

However, as Hughes is quick to point out, Collins's handling of "drawn-out mystification or impending menace" (19), particularly in The Moonstone, is so masterful, so carefully controlled and titrated, that the reader revels not so much in successive rises as in the final denouement, which harmonizes all competing narratives and executes Nemesis character by character.

No sooner had the new subgenre won a popular following than M. E. Braddon and other Punch writers, as we have seen, lampooned it. Hughes (1980) makes a convincing case for Trollope's The Eustace Diamonds as a parody of Collins's The Moonstone, complete with a young lady's falling under suspicion of having stolen her own jewels, two robberies, and a bumbling detective. [1] At about the same time, the prospect of the royalties from producing a best-seller probably inspired young architect Thomas Hardy to write his own Sensation Novel, Desperate Remedies. Published anonymously, the potboiler utilizes many of Collins's strategies, albeit far less effectively: "murder, blackmail, illegitimacy, impersonation, eavesdropping, multiple secrets, a suggestion of bigamy, [and] amateur and professional detectives" (Hughes 173) are all present. Even those scholars and critics who assert that Hardy was one of the most original prose-fiction writers of the latter part of the nineteenth century must concede that, as the plots of even some of greater novels such as The Mayor of Casterbridge and Tess of the D'Urbervilles attest, Hardy never quite lost his taste for Sensation, even if the reading public had tired of it after 1880. In particular, Hardy had a fondness for such standard Sensation strategies as the instalment closings known as "curtains," strongly delineated characters. numerous coincidences upon which the plot seems to hinge, bigamous or secret marriages, illegitimacy, and the return-from-the dead scenario, even providing what H. L. Mansel in 1863 had termed "some demon in human shape" (360) in the person of Alec D'Urberville.

Notes

[1] His argument is based on that of H. J. W. Milley in Studies in Philology, October 1939, pp. 651-63. The Eustace Diamonds ran serially in the Fortnightly Review in 1871; The Moonstone ran serially in All the Year Round in 1868.

Related material

- The Victorian Sensation Novel: Selected Bibliography

- A Philip V. Allingham's review of The Cambridge Companion to Sensation Fiction

- Sensational literature, the “unknown public,” and the political implications of this genre

- “Miss Braddon’s Novels” (Lady Audley's Secret and Aurora Floyd) — 1863 review in The Reader

- “Miss Braddon’s Last Novel: The Doctor’s Wife” — 1864 review in The Reader

Bibliography

Allingham, Philip V. "Sensation Novel Elements in The London Graphic's Twenty-Part Serialisation of Hardy's The Mayor of Casterbridge (January through May, 1886)." The Thomas Hardy Year Book 31: 34-64.

Edwards, P. D. "Sensation Novels." Victorian Britain: An Encyclopedia. Ed. Sally Mitchell. London and New York: Garland, 1988. Pp. 703-704.

Hughes, Winifred. The Maniac in the Cellar: Sensation Novels of the 1860s. Princeton, NJ: Princeton U. P., 1980.

Kalikoff, Beth. Murder and Moral Decay in Victorian Popular Literature. Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Research, 1986.

Manse, H. L. "Sensation Novels." Quarterly Review 113 (April 1863): 482-495, 501-506, 512-514; rpt. Dictionary of Literary Biography, Vol. 18: Victorian Novelists After 1885. Ed. Ira B. Nadel and William E. Fredeman. Detroit: Gale Research, 1983.

Marshall, Gail. "Psychology and the sensation novel." Victorian Fiction. London and New York: Oxford UP, 2002. Pp. 57-63.

"Mary Elizabeth (M. E.) Braddon: 1835-1915." http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/masterpiece/wives/writers/braddon.html

Nadel, Ira B. "Wilkie Collins." Dictionary of Literary Biography, Vol. 18: Victorian Novelists After 1885. Ed. Ira B. Nadel and William E. Fredeman. Detroit: Gale Research, 1983. Pp. 61-77.

Nayder, Lillian. Unequal Partners: Charles Dickens, Wilkie Collins, and Victorian Authorship. Ithaca, NY, and London: Cornell U. P., 2002.

Peters, Catherine. The King of Inventors: A Life of Wilkie Collins. London: Minerva, 1992.

Last modified 27 September 2025