These questions were originally created for English 394: The Victorian Novel from Dickens to Hardy, at the University of British Columbia, Summer Session Two, 1989. They have been augmented with pertinent excerpts from Tillotson's seminal criticism of the early Victorian novel for English 3412 (Victorian Fiction), Lakehead University, January through May 2004. For additional questions click on the "Contexts" icon at the foot of the screen.

Question 18. "Part Sixteen: Introductory" (pp. 115-125) — The Novel-with-a-Thesis

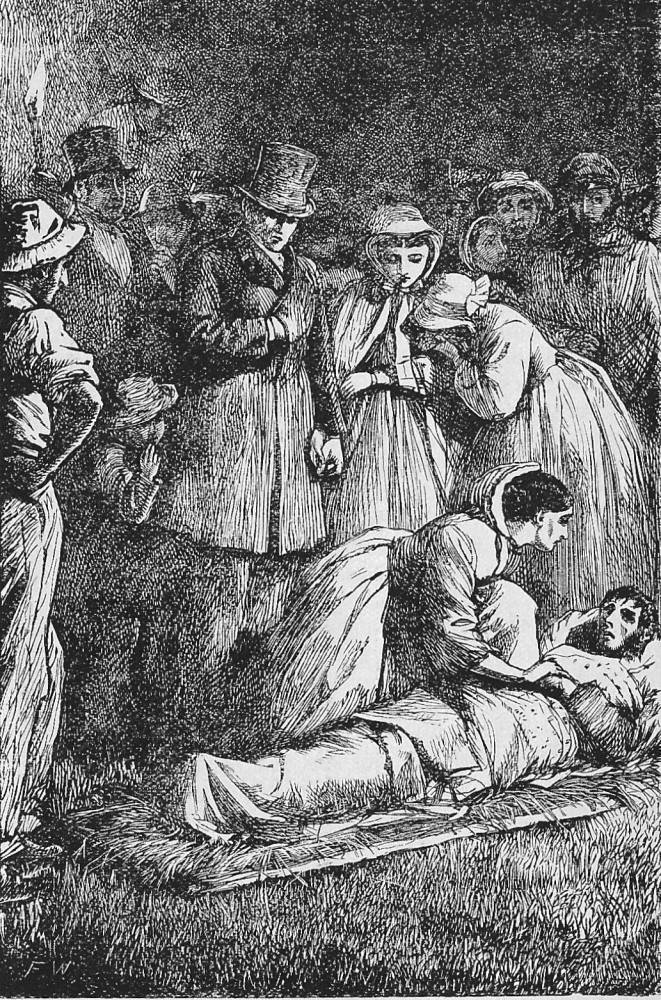

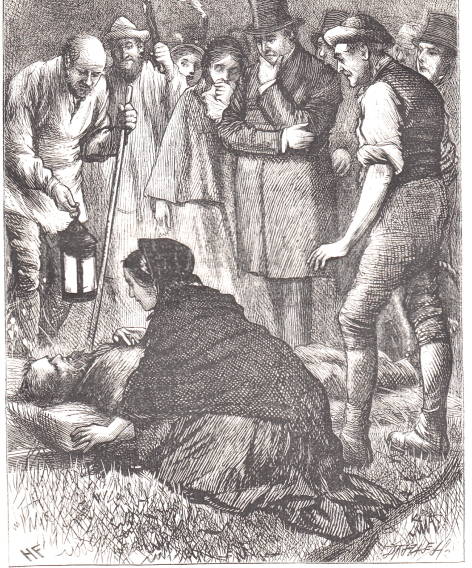

Left: Fred Walker's realisation of the scene in which the rescue party bring a mangled Stephen Blackpool out of an abandoned mine shaft near Coketown in Dickens's Hard Times for These Times: Stephen Blackpool recovered from the Old Hell Shaft (Book the Third, "Garnering," Chapter VI, "The Starlight," originally published in Household Words, 1 April-12 August 1854). Centre: Felix Octavius Carr Darley's realisation of the scene in which the women discover that Stephen has fallen into the shaft: She shuddered to approach the pit, frontispiece for the 1863 Household Edition, vol. 2. Right: Harry French's dramatic realisation of Rachael's bending over the battered body of the factory-worker in She stooped down on the grass at his side, and bent over him (1877). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Many novelists in the forties and fifties chose the stony and thorny ground of social and religious controversy; many different motives converged to make the 'novel-with-a-purpose' a common type, and as [115/116] vulnerable to mockery as its predecessors. That compendious burlesque, Charley Tudor's Sir Anthony Allan-a-dale, a novel in halfpenny daily numbers, and a historical romance, is also a novel with a purpose — several purposes:

'The editor says that we must always have a slap at some of the iniquities of our times. He gave more three or four to choose from; there was adulteration of food, and the want of education for the poor, and street music, and the miscellaneous sale of poisons . . . Then we have the tria of the apothecary's boy; that is an excellent episode, and gives me a grand hit at the absurdity of our criminal code.' . . . . 1 [116/117]

Novelists who, for one reason or another, avoided the thesis-novel themselves might be regarded as interested critics; but already in 1850 reviewers were complaining of the growing practice of

writing political pamphlets, ethical treatises, and social dissertations in the disguise of novels . . . To open a book under the expectation of deriving from it a certain sort of pleasure, with perhaps, a few wholesome truths scattered amongst the leaves, and to find ourselves entrapped into an essay upon labour and capital, is by no means agreeable. 1

. . . by becoming too preoccupied with outward matters, [a novelist] may lose touch with the other world of imaginative reality; the novelist's 'purpose' may too firmly predestine the fates of his characters, destroying both suspense and spontaneity. 2 Yet there are gradations. Mary Barton may still be the least read of Mrs. Gaskell's novels, as is Hard Times of Dickens's; but most modern readers can get more these than from Sybil [1845] or Yeast [1851] . . . . [118]

Notes, p. 116

1 Described by Charley to his friend Norman in ch. xix of Trollope's Three Clerks (1858).

Notes, p. 117

1 Fraser's (November 1850) , p. 575; the books under review included Alton Locke. But some reviewers took a different line, and complained when they found lack of 'purpose'. A writer in Tait's Edinburgh Magazine (February 1848), pp. 138-40, was perplexed by Wuthering Heights, which did not 'dissect any portion of existing society'. In the end he found a 'moral' in the 'volumes': 'they show what Satan could do with the law of Entail'. [117]

Notes, p. 118

1 William Sewell's Hawkstone (1845) is an extreme instance; the Evangelical is allowed to repent after many sufferings, but the atheist falls into melted lead and the Jesuit is eaten by rats. (It was Sewell who burnt Froude's Nemesis of Faith [an epistolary-philosophical novel, 1849], and who 'edited' the early novels of his sister Elizabeth Sewell.)

Question 18. "Part Sixteen: Introductory" (pp. 115-125)

18. What were some of the topics hammered home in the thesis-novel or novel-with-a-purpose? What were the aesthetic dangers and benefits implicit in writing such a novel?

Bibliography

Tillotson, Kathleen. Novels of the Eighteen-Forties. Oxford: Clarendon, 1955, rpt. 1983.

Vann, J. Don. Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: Modern Language Association, 1985.

Created 25 December 2004

Last modified 25 January 2024