Dedicated to Rudie, our son and daughter-in-law's rescue dog and family pet. A dearly loved and gentle soul, she lived to a very ripe old age, and passed away during the writing of this piece.

rowing understanding of both domestic and wild animals, and new knowledge about evolution and our relationship to the rest of the animal world, brought more commitment to animal welfare. Legislation now curbed some specific acts of cruelty towards dogs: using them to pull loads, for example, was banned in London in 1839, and the ban went nationwide in 1854 (see O'Sullivan 149). Campaigning on dogs' behalf would continue throughout the period. In 1895, for instance, the RSPCA, now one of the nation's favourite charities, brought a well-publicised case against Harry Cooper, a bar steward, and Robert and Mary Carling, who cropped Cooper's dog's ears for him. Despite the fact that the dog was a Bull Terrier, and cropped ears were still the recognised show standard for the breed, the RSPCA won. Unable to pay the fine, the defendants were sent to prison (Warboys et al. 200-201). By this time, the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals was one of the nation's favourite charities.

The first animal shelter

Yet one problem was particularly hard to tackle. In 1874 alone, and in London alone, "10,156 stray dogs [were] 'taken up'" from the streets ("The Metropolitan Police," 166). A different kind of initiative was needed to cope with these abandoned and starving creatures. Such an effort was already underway. The most famous animal shelter in Britain is also the oldest. Battersea Dogs' and Cats' Home was established in its present place in 1871, and its history goes back over ten years before that, to when the middle-aged Mary Tealby (1801-1865) started a small refuge in Holloway in 1860. After helping a friend tend an abandoned dog, she started caring for some strays herself. As the numbers grew, she found some unused stabling in the locality, where she could take them, feed them and bring them back to health. Sometimes, they were just lost. Seeing advertisements for the refuge, their owners turned up and were overjoyed to be reunited with their pets. More often, Tealby was able to settle her dogs with new and loving owners.

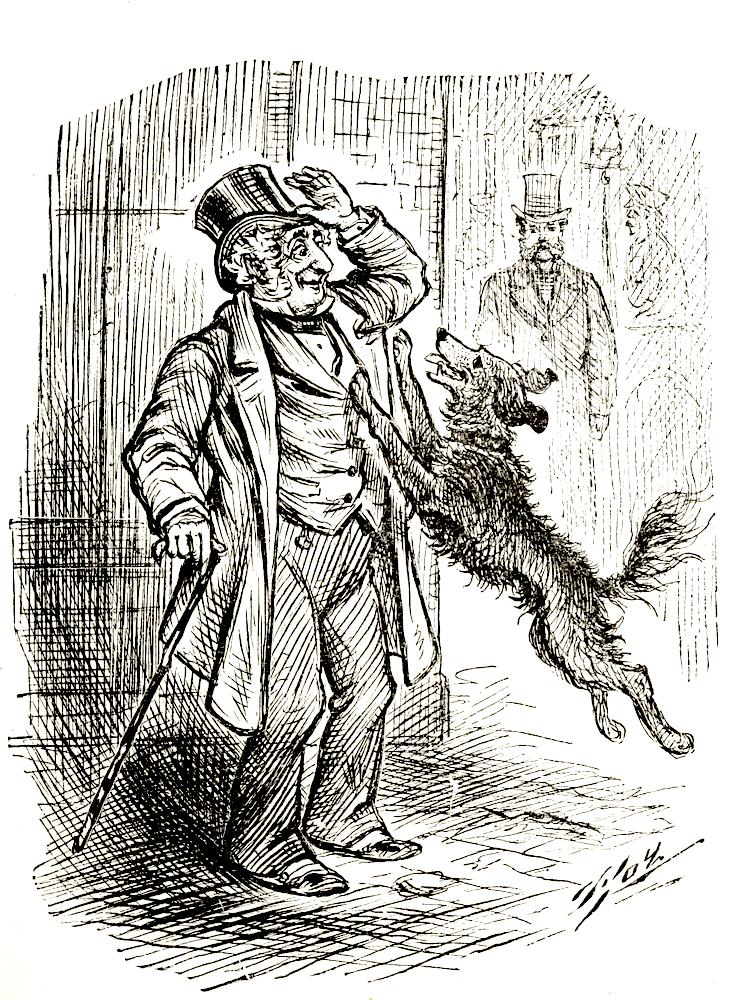

Sport, finding his way home after many adventures, recognises his master's father — the prelude to an even happier reunion with his master ("Sport and His Travels," Ingersoll, facing p. 36).

With the support of Tealby's brother Edward and others, the venture was now put on a formal footing. The first committee meeting for the new organisation was held on 27 November 1860, in the RSPCA premises on Pall Mall. It was chaired by the MP for Tamworth, Warwickshire, Lord Raynham, who was never slow to express his views on animal cruelty, and who did what he could himself to alleviate animals' sufferings. He was the ideal person to represent this cause. Other important people had come forward, too, among them Tennyson's sister, Emily, who was one of the first committee members.

Useful though all this was, the scale of the problem was still huge. Tealby needed funds, and for funds she needed publicity. Early press coverage of the venture was sceptical about it, to say the least. Its request for contributions in the Times of 18 October 1860 was placed directly below a letter by "A.B." complaining that its priorities were wrong: "Surely charity can be better bestowed by thinking of homes for wandering and starving children" (6). Worse, an editorial on the same day was even more scathing, ending "Why should there not be a home for rats? The great and unmerited sufferings of those interesting members of the brute creation have not yet attracted the notice they deserve" (8).

Dickens and the new shelter

Fortunately, in 1861, the fledgling organisation was helped by a highly influential person: Charles Dickens. Dickens had turned thirty before he got his first dog, Timber. But after that he always had dogs, and, as his friend and biographer John Forster noted, they were "a great enjoyment to him" (II: 266). A story he often told was that once he got frostbite, or a touch of it, and had to limp painfully home in the snow. On that occasion, instead of bounding ahead in their usual lively way, his dogs Turk and Linda accompanied him slowly and anxiously, with evident concern. "He was greatly moved by the circumstance, and often referred to it," reported Forster (II: 493). Dickens was therefore more than ready to take up the cause of abandoned dogs, and published an article about them in his popular weekly magazine All the Year Round, for the week of 2 August 1862.

Entitled "Two Dog-Shows," the article compares a fashionable dog show held in Islington, north London, with the considerably less fashionable dogs' temporary refuge then being run nearby by Tealby. At the "Monster Dog Show" more than a thousand dogs were displayed — including, as the Times reported, the Duke of Beaufort's whole pack of forty foxhounds (see "Dog Show"). The author describes seeing many different breeds there, the prizewinners seeming to him to have "something of the quiet triumph of human success in their aspect" (493), and others too having various comic points. But he has nothing but admiration for the Clumber spaniels, seeing them as "beautiful and rare animals" (494). At the refuge, however, the other "dog-show" that he visits, the only specimens to be seen were "the Lost Dogs of the Metropolis ... poor vagrant homeless curs" (495) picked up from the roadside where they had been dying of starvation.

Like other contributions to All the Year Round, this piece was anonymous. Critical opinion is divided: in all likelihood, it was written by Dickens himself; but it is still sometimes attributed to his like-minded contributor, John Hollingshead (see Warboys et al, p. 244, n.42). Hollingshead (1827-1904) is certainly worth mentioning here as a long-time supporter of the cause. Speaking in a named essay on "Happy Dogs" in 1865, he expressed his pleasure that "[T]his charitable refuge for lost and starving dogs is now a permanent London institution" (144). He also described the dog shelter much later, in 1895, as "an old and favourite asylum of mine" (II: 124). But whether it was Dickens or Hollingshead who wrote it, Dickens was the one who published it, and it was "hugely influential" (Jenkins 66). Tealby's project flourished.

The move to Battersea

The Battersea home in its earliest years, reproduced here by kind permission of Battersea Dogs' and Cats' Home.

Before long, there were just too many dogs for the small stable yard. So in 1871, several years after Tealby's death, a larger space was found on the south side of London, at Battersea. From now on the home would always be associated with the name of the new place. In 1885, the Battersea home began taking in cats, too. Not long afterwards, in December 1885, Queen Victoria gladly agreed to become its patron. According to the Times of 22 February 1990 (looking back to these days), in 1896 alone, it took in 42,614 animals. Equally important, by 1990 it was receiving as many as 70,000 visitors a year. Among these visitors were many who hoped to adopt a pet and make up for whatever sufferings the animal had had in the past.

The article in All the Year Round had praised the original home as an "extraordinary monument of the remarkable affection with which English people regard the race of dogs; an evidence of that hidden fund of feeling which survives in some hearts even in the rough ordeal of London life in the nineteenth century" (497). It is also a monument to the particular individuals involved in its history, from kind-hearted, hard-working Mary Tealby, to Dickens and Hollingshead — who never stopped campaigning for it.

Rescue dogs are the best breed of all! Reproduced here by kind permission of Battersea Dogs' and Cats' Home.

Battersea Dogs' and Cats' Home has now cared for over 3.1 million animals "Our History"). It is very different today from how it was at the beginning, with centres in Berkshire and Kent as well as in Battersea. Thanks mainly to public support, the animals have comfortable quarters, and all the attention they need until they can be taken into new families, where they will more than repay the care they require.

As for the Victorians, at the end of the era there was still a long way to go in educating the public. Wild animals were still penned in concrete cages at the zoo, and elephants were still performing in circus rings. Decades would pass before their treatment improved. Some so-called blood sports continue to this day. More insidiously, habitats are being destroyed and species are becoming extinct at an alarming rate. The fact that we are being made aware of this now, and that the younger generation is being encouraged to have a new respect for the natural world, is the brightest ray of hope for the future.

Related Material

- The Victorians and Animals: An Introduction

- Part I: Animals as Part of the Household

- Part II: Animals in Entertainment

- Part III: Studying Animals

- Part IV: Working Animals

- [Offsite] Battersea (the Home's website)

Bibliography

Ayres, Brenda. Victorians and Their Animals: Beast on a Leash. London: Routledge, 2019.

"The Dog Show." The Times. 12 February 1891: 10. Times Digital Archive. Web. 18 October 2020.

"Dog Show at the New Agricultural Hall." The Times. 23 June 1862: 12. Times Digital Archive. Web. 18 October 2020.

Forster, John. The Life of Charles Dickens. II. Library ed. London: Chapman and Hall, 1876.

Hollingshead, John. "Happy Dogs." To-day: Essays and Miscellanies. I: Day Thoughts. London: Groombridge & Sons, 1865. Internet Archive. Contributed by the Asiatic Society of Mumbai. Web. 18 October 2020.

_____. My Lifetime, Vol. II. London: Sampson Low, Marston & Co., 1895. Internet Archive. Contributed by the library of Harvard University. Web. 18 October 2020.

Ingersoll, Ernest. "Sport and His Travels." Dogs. Chicago: Interstate Publishing, 1879. 34-41. Internet Archive. Contributed by the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Web. 18 October 2020.

Jenkins, Garry. A Home of Their Own: The Heartwarming 150-year History of Battersea Dogs' and Cats' Home. London: Bantam, 2011.

Kean, H. "Tealby [née Bates], Mary (1801–1865), animal welfare organizer." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online ed. Web. 18 October 2020.

"The Metropolitan Police." The Graphic 10 (July-December 1874): 166. Hathi Trust. Contributed by the New York Public Library. Web. 18 October 2020.

"Our History." Battersea. Web. 18 October 2020. [This has a useful timeline.]

"Two Dog-Shows." All the Year Round 7-8 (1862-63): 493-97. Hathi Trust, contributed by the University of California Library. Web. 18 October 2020.

Worboys, Michael, Julie-Marie Strange, and Neil Pemberton. The invention of the Modern Dog: Breed and Blood in Victorian Britain. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018. [Review]

Created 18 October 2020