lthough the long term causes of the Crimean War

probably were more crucial, the immediate causes of the war — ostensibly, at

least — were over religion, particularly over the protectorship of the Holy

Places in Jerusalem. The Holy Land was part of the Muslim Ottoman Empire but

also was the home of Judaism and Christianity. In the Middle Ages, Christian

Europe and the Muslim east had fought the Crusades over control of this land.

However, the Christian Church was divided into numerous small denominations.

The Eastern Orthodox Church and Roman Catholic Church were the two major branches

of Christianity. Unfortunately, these main denominations could not work together.

Both of them wanted to control the Holy Places.

lthough the long term causes of the Crimean War

probably were more crucial, the immediate causes of the war — ostensibly, at

least — were over religion, particularly over the protectorship of the Holy

Places in Jerusalem. The Holy Land was part of the Muslim Ottoman Empire but

also was the home of Judaism and Christianity. In the Middle Ages, Christian

Europe and the Muslim east had fought the Crusades over control of this land.

However, the Christian Church was divided into numerous small denominations.

The Eastern Orthodox Church and Roman Catholic Church were the two major branches

of Christianity. Unfortunately, these main denominations could not work together.

Both of them wanted to control the Holy Places.

In 1690 the Ottoman Sultan granted to the Roman Catholic Church the dominant authority in all the churches in Nazareth, Bethlehem and Jerusalem; then in 1740 a Franco-Turkish treaty stated that Roman Catholic monks should protect the Holy Places. This was intended to ensure the safety of Christians and to enable pilgrimages to Jerusalem; furthermore, the French had asserted their right to rebuild the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem as a Catholic church. However, between 1740 and 1820 the influence of the Roman Catholic Church had been allowed to lapse by natural erosion: there were not many Roman Catholics in that part of the world and Christians tended to belong to the Eastern Orthodox Church. Consequently, protection of the Holy Places had gradually devolved to Orthodox monks. Russia represented the Orthodox Church as its protector and Czar Nicholas I seems to have thought that he had been ordained by God as the leader of the Orthodox Church and the protector of Orthodox Christians. By the 1840s, Russian pilgrims were flocking to the Holy Land, which gave the Czar the excuse to demand that the Russians should be able to provide some form of protection for his subjects there.

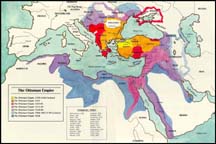

Map of the Ottoman Empire. The map has been taken from the Ottoman Souvenir website with the kind permission of the webmaster, Musa Gursoy, to whom thanks are due. Copyright, of course, remains with the Ottoman Souvenir web. Click on the image for a larger view

In 1850, Louis Napoleon of France decided to champion the cause of Roman Catholics to control the Holy Places; technically he was within his rights but his demands on behalf of the Church allowed him to divert attention from problems in France and also helped him to advocate the idea of a second French Empire. In order to win the support of the majority of the French, Louis Napoleon needed to be seen as a 'good Catholic'; he also wanted to wreak his revenge on Czar Nicholas I for the insult of "mon ami" rather than the traditional "mon frère".

Traditionally, the Pope nominated the Catholic Patriarch of Jerusalem but over many years the office had become a meaningless title; the Patriarch did nothing and lived in Rome. However, in 1847, Pope Pius IX — who had been elected the previous year — sent the Patriarch to live in Jerusalem because in 1845 the Orthodox Patriarch Cyril had chosen to go to live in the city. In 1847 and 1848 there were unseemly scuffles between Catholic and Orthodox Christian monks and priests in Jerusalem; the representatives of the Orthodox Church emerged truimphant: for example, at the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem, Catholics had placed a silver star to commemorate the place of Jesus' birth. It was prised out and stolen, allegedly by Orthodox monks.

The Turks disliked the Russo-French conflict that was taking place on Turkish territory and the Sultan established a commission to examine the claims of the French. France suggested that the Catholic and Orthodox Churches should have joint control over the Holy Places: this led to an uproar in Russia and then deadlock. In February 1850 the Turks sent a diplomatic note to the French, giving two keys to the great door of the Church of the Nativity to the representatives of the Catholic Church. At the same time, the Porte sent a firman [decree] giving secret assurances to the Orthodox Church that the French keys would not fit the lock. However, by the end of 1852 the French had seized control of the Holy Places. This was seen by the Russians as a challenge to their prestige and policy; the Czar also saw Turkey falling under 'foreign' control. Nicholas I wanted Russia to have control over the Near East with the agreement of the western powers, especially Britain, so that Russian expansion could take place peacefully. Nicholas thought that this would be easy to achieve since the Earl of Aberdeen was the British Prime Minister.

In 1844, Czar Nicholas I had paid a royal visit to Britain. Whilst there he talked to staff at the Foreign Office and also to Aberdeen. Informal discussions took place about the Eastern Question but Aberdeen's approach was very different from the traditional scheme of Britain's foreign policy. During the discussions, Aberdeen expressed a very understated policy and consequently was conciliatory to the Czar who went away with misconceptions about Britain's attitude to the Eastern Question as a result. Aberdeen gave the impression of despair and disgust at the corruption of Turkey. The Czar therefore suggested that perhaps a way forward could be to partition Turkey. Aberdeen was not firm in denouncing these ideas or in stating British policy unequivocally, therefore the Czar felt that the partition of Turkey was viable and also that Britain was tired of defending Turkey and would not go to war over the Turkish Empire. Not only did Aberdeen give 'wrong messages' to the Czar, he also decided that the Czar would not go to war over Turkey.

In 1853, the Menschikov Mission arrived in Constantinople from Russia. Menschikov was a Russian soldier and diplomat who was told to coerce the Sultan into giving concessions to Russia within the Turkish empire. The Sultan faced a number of domestic problems at this time: the crisis over the Holy Places; an insurrection in Montenegro; a threatened coup in Serbia. Menschikov told the Ottoman officials that he was unhappy about the Sultan's treatment of Orthodox Christians in the empire and that in order for Russia and Turkey to remain on good terms, the two nations should approve a 'solemn agreement' so that the Russians could redress the grievances of Christian subjects in Turkey. Menschikov demanded the establishment of a Russian protectorate over all Orthodox subjects in the Ottoman Empire — laity as well as clergy: the total number of people who fell into this category was about twelve million. Russian demands led to fears in the Porte that Turkish independence was being threatened; as ever, the Sultan appealed to the Great Powers of Europe for protection against Russian encroachments.

Whilst he was in Constantinople, Menschikov met the British ambassador for discussions about the future of the Ottoman Empire: the British Ambassador was Stratford Canning, a cousin of George Canning. Stratford Canning — who had been created Viscount de Redcliff in 1852 (hereafter, Stratford) — had to make his own decisions because he was not getting a positive lead from the Foreign Office in Britain: the Foreign Secretary in Aberdeen's government was the Earl of Clarendon. Stratford had warned the Foreign Office of potential problems in Turkey and had explained the build-up of tension; he advised a high-profile approach by Britain but got little reaction. It was felt by the government that Stratford was alarmist and was exaggerating. No-one took him really seriously, except Palmerston who advised strong, prompt and effective action. It did not help his position that Stratford disliked the Russians on general and personal grounds. In 1832 he had been recommended as the Ambassador to Russia, but had been flatly and rudely rejected by the Czar because of his relationship to George Canning. Stratford had never forgotten the snub.

Because of Britain's long-standing policy of maintaining the integrity of the Turkish Empire, Stratford had access to the Sultan and encouraged him to refuse the Czar's demands. Stratford almost promised British protection for the Sultan: this was very much over-stepping his brief. Stratford followed a strong line of his own which was in accord with earlier British foreign policy and since he was receiving little guidance from London on how to deal with the problem, he felt that his approach was appropriate to the circumstances. The Sultan resisted Menschikov's demands; by the summer of 1853 Menschikov realised that he was making no progress in Turkey and returned to St. Petersburg to inform the Czar of the situation which in Russian policy appeared to be a failure while France apparently gained. The Czar felt shamed by the lack of success, therefore he decided to find out firstly, how strong the Sultan was and then how strong was Britain's intention to resist Russian encroachment. He thought - after his discussions in 1844 - that Aberdeen would recall Stratford and not fight.

In 1853, Russia invaded Turkish Moldavia and Wallachia which were autonomous areas within the Ottoman Empire. Nicholas' aim was not territorial conquest or to provoke a war but rather to bully and test Turkey, to see what the response would be and to force the Sultan to give guarantees to the Orthodox Church that Christians would be protected from harm. Czar Nicholas I did not expect either a hostile response from Britain or Anglo-French co-operation, given that the two countries were seen as 'natural' enemies. The result of Nicholas' actions were far from what he expected and his gamble did not pay off because he actually put pressure on the European peace.

- France — as personified by Louis Napoleon, now the Emperor Napoleon III — became aggressive and noisy.

- Britain was alarmed because of the threat to Turkey from the perceived Russian expansionist activity. There was therefore much activity with Britain's Mediterranean fleet.

- Austria-Hungary feared invasion because Russia had crossed the Danube, which was Austria's outlet to the Black Sea. Austria therefore began to mobilise.

- When Austria-Hungary began to mobilize, so Prussia started a partial mobilisation, fearing a threat to the Germanic Confederation.

This was very much like the Mehemmet Ali crisis of 1839 which led to the first London Conference so a similar situation had already been dealt with successfully by using international co-operation. The Powers realised this, and did not want a war over a misunderstanding; therefore they called a Conference of Vienna in 1853. It was attended by Russia, Austria-Hungary, Prussia, Turkey, Britain and France, to hammer out a compromise to defuse the situation. They produced the Vienna Note, an official diplomatic document of mediation proposing a compromise which Russia was prepared to accept because she did not want war. It said that the Czar should evacuate Moldavia and Wallachia but that Russia, as the protector of the Orthodox Church, should have nominal protection of Orthodox Christians in the Ottoman Empire and of the Holy Places. The Note confirmed the status quo: neither Russia nor France got anything, but face was saved. Up to now, things were similar to the 1839 crisis: potential problems had been neutralised and a compromise had been arranged. However, previously the Powers had backed up their decisions with joint military support. This was the watershed of the crisis which could have ended at this point, but things went wrong and resulted in the Crimean War. There was no joint military force set up to follow the Note and there was no emphatic diplomacy to make the Sultan accept the Note — unlike the 1839 London Conference after which troops were put in the field to enforce the decisions of the Powers.

There was a positive response to the Vienna Note from the Russians who agreed to it and began to evacuate Moldavia and Wallachia. This proves that Russia was just probing into the Ottoman Empire and did not want war. She had been given nominal protection of the Holy Places and was appeased, if not satisfied. Russia would always make a diplomatic retreat if faced with strong opposition. Unfortunately, in October 1853 the Sultan rejected the Note and declared war on Russia because Stratford had assured the Sultan of British backing and also because Turkish territory had been invaded. The Sultan wanted revenge and he thought that he was assured of British backing. In the past, the Powers had used conjoint force to enforce their views on the Sultan but this time there was no military back-up for their decision. The Powers thought that the Note was enough and they were unable to co-operate among themselves for a variety of reasons:

- Austria-Hungary did not want to get involved in disputes with any of the major Powers and so chose to remain neutral in this instance. She was more concerned with Prussian expansion and the Italian revolts. She feared losing her Italian lands

- Austria-Hungary and Prussia were mutually suspicious, and Prussia was expanding

- Russia was opposed by Britain and France

- Britain (under Aberdeen) was indecisive

- Russia was disappointed with Austria-Hungary's attitude, after Russian help in suppressing the Hungarian revolt in 1848.

The Sultan was allowed to pursue his own policies because of the diplomatic breakdown; at the same time Stratford was assuring him of British support. By sheer coincidence, a small Anglo-French fleet entered the Straits a few days after the Sultan declared war on Russia (in contravention of the Straits Convention), to protect the Sultan from an internal rebellion. This seemed to endorse Stratford's promise of British help. Turkey's declaration of war and the Anglo-French presence in the Straits gave Russia a reason to retaliate.

In November 1853 the Russian Black Sea fleet based at Sevastopol and the Turkish fleet met at the Battle of Sinope. The Turkish fleet was sunk. It was a provocative action by Russia because she had no real reason to fear Turkey. The affair was reported in the British press as the 'Massacre of Sinope', and caused fever-pitch anti-Russian feeling among the public. It also strengthened the 'war faction' in the Cabinet, for unexplained and obscure reasons. Perhaps a combination of reasons were responsible: it has been argued that

- perhaps the long peace — since 1815 — had created a desire for war. It provoked patriotism and expressed the British cock-sure attitude which resulted from her economic, territorial and free trade strength

- Sinope was a naval victory: Russia clearly had a Black Sea fleet which needed to be defeated before it got into the Mediterranean. The British felt that the Russian naval threat could not be allowed to grow

- Britain was becoming more and more dependent on trade, especially with India and the east: Sinope followed the Great Exhibition of 1851 that had demonstrated Britain's industrial pre-eminence in the world. The Mediterranean trade and the routes to India could not be jeopardised

- In Britain, the 'war party' had been growing since the summer of 1853.

Even moderate papers like The Times demanded retribution before Russia over-ran Turkey: Russia could do this legitimately, since Turkey was the country that had declared war on Russia. Demands were made for a British fleet to be sent to the Straits, but the Cabinet was divided between 'war' and 'peace' factions, resulting in indecision. Clarendon, the British Foreign Secretary said that Britain was 'drifting towards war' — something that Aberdeen was trying to avoid. However, he was in an impossible position because not to help Turkey would lead to an expansion of Russian power and to help Turkey meant war. Aberdeen let events drift towards war by indecision in preventing it. By Christmas 1853, the British government was left with little choice.

In the winter of 1853, Lord John Russell proposed a Reform Bill in an attempt to strengthen the Coalition. It was rejected but Palmerston resigned to show his hostility to parliamentary reform. His resignation coincided with the government's indecision over Sinope, but was misinterpreted as a sign of Palmerston's disapproval of the government's foreign policy. That whipped up the war party's enthusiasm in Britain. The British government's dithering continued until March 1854, largely because of Cabinet divisions; then in March 1854 Britain and France jointly declared war on Russia ostensibly in defence of Turkey, but really to control Russia expansionism.

From the Vienna Note onwards, it is difficult to see how war could have been avoided: this was even Gladstone's view. Palmerston may have been right: stronger action taken earlier might have stopped Russia. There was some element of Russia calling Britain's bluff, following the Czar's informal talks with Aberdeen in 1844, when Aberdeen's low-profile approach had intimated to the Czar that Britain would never go to war over Turkey. There is much evidence to suggest that Czar Nicholas I was under the illusion that British foreign policy towards Turkey had changed: even that Britain might consider the partition of Turkey, to end the problem; certainly he believed that Britain would not fight over the issue. The long gap of four months before Britain did declare war strengthened Russia's misapprehension. They had expected Britain to rush in, if she was going to do anything. It was a shock for the Czar to discover that British policy towards the Ottoman Empire had not changed.Who was responsible for the Crimean War?

The Sultan? Had he been encouraged to act like this by past events? Stratford Stratford had said that Britain would help, so the Sultan declared war on Russia because he knew the Allies would come to his rescue.

Russia? They had always looked to expand into Turkey but withdrew if strongly opposed.

Britain? Aberdeen's apparent change of policy might have encouraged Russia.

France? Napoleon III was looking for prestige.

Austria? She could have resisted Russia and joined the Allies.

Every nation's position is understandable, although similar scenarios had been defused earlier. There was actually more reason for a war in 1839 than in 1854.

Last modified 7 May 2002