University College School

The founding colleges of the University of London both set up boys' schools to prepare their largely middle-class students for admission to higher education. By coincidence, both schools helped to produce some famous artists.

Lord Henry Brougham, to whom the poet Thomas Campbell had originally proposed the idea of a metropolitan university, was again one of the prime movers in the establishment of University College School. It was founded in a Gower Street house in 1830, the year in which Brougham became a Lord. The school either outgrew its premises or failed to flourish (according to Christopher Stray), and was moved into the college itself in 1832, eventually occupying a new south wing of the college building, designed by T. Hayter Lewis in keeping with William Wilkins's main building. Here it certainly did flourish, despite or because of being true to the ideals of its parent college — it was amazingly progressive for its time, with no chapel, no playing fields, no caning, no religious instruction, no Latin and Greek verse composition, and no compulsory subjects at all. Natural Science, however, did appear on the curriculum, to the delight of one early pupil, Joseph Lister.

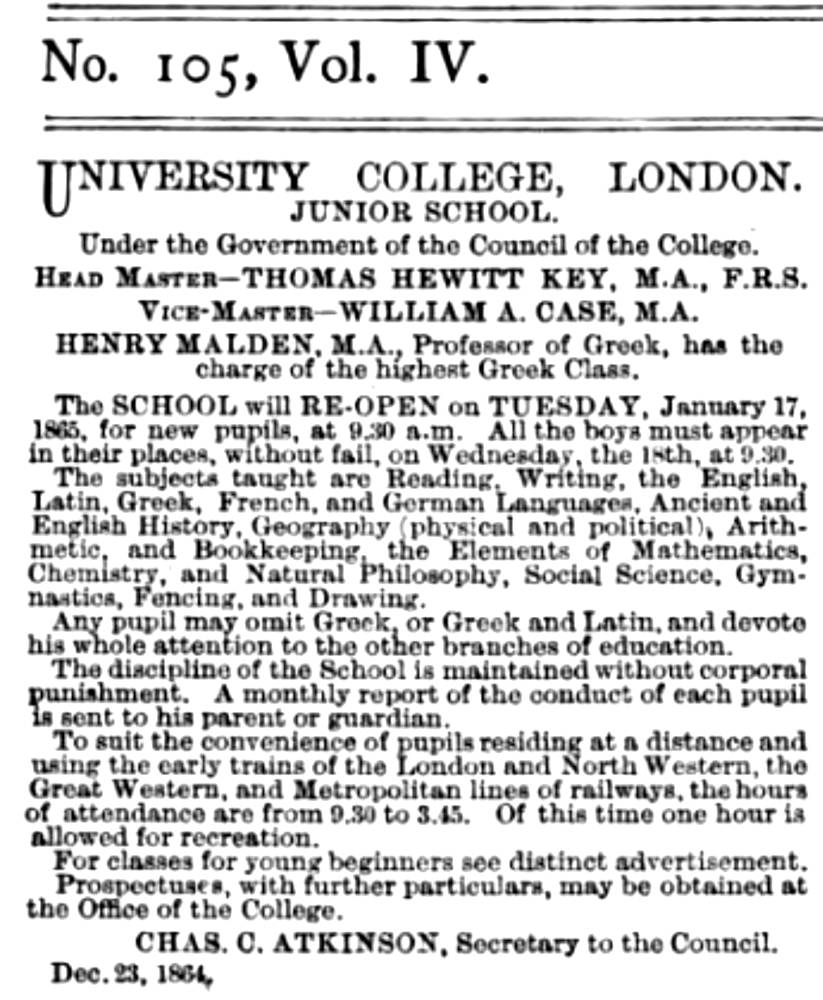

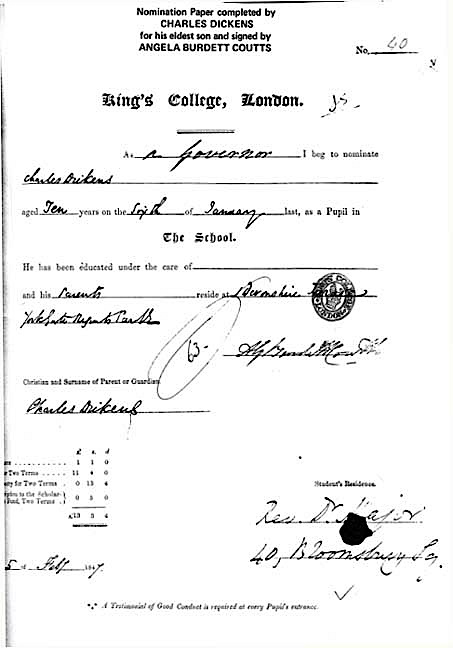

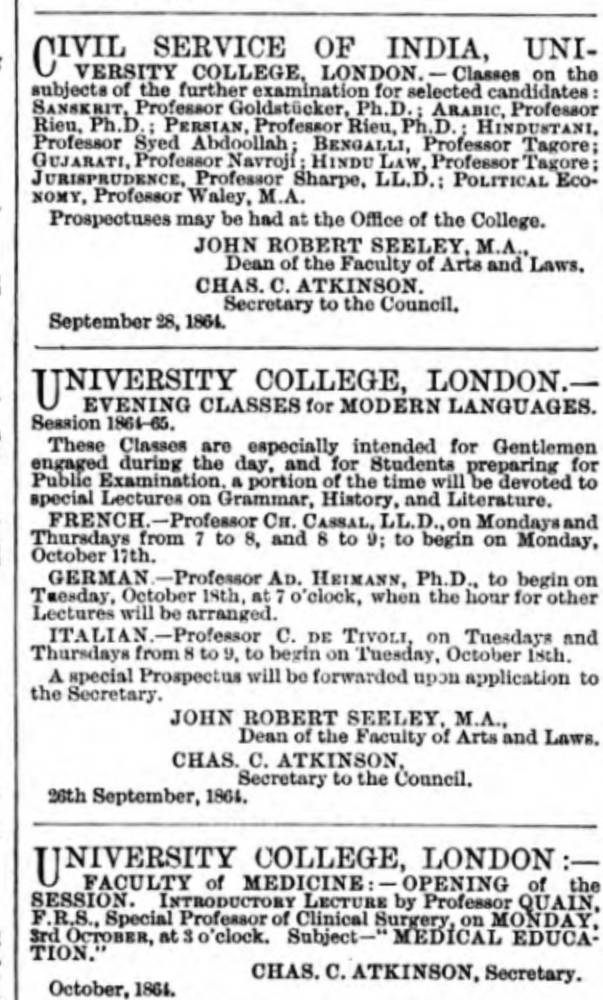

Left: Notice in The Reader about the University College London’s Junior School Middle: Nomination paper for Charles Dickens Jr.. Right: Three notices about UCL courses for the Indian Civil Service, Medicine, and modern languages.. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

At first under joint headship, and then solely under the headship of Latin scholar Thomas Hewitt Key (1799-1875), University College School's enrolment grew to well over 600 by the mid-seventies. Amongst its other early pupils was Moses Angel, the future headmaster of the Jews' Free School in the East End, which would become probably the biggest school in the world (Picard 296). Some other notable Victorians who were educated at University College School were Henry Doulton, of pottery fame, who came to love literature there; the artist Frederic (the future Lord) Leighton, though only intermittently because of his family's globetrotting; the sculptor Hamo Thornycroft; and the writer Ford Madox Ford.

King's College School

King's College's junior department was tucked away in its "subterranean" or "infernal regions" (Hearnshaw 103, 153), i.e., its basement. To begin with, it was the most successful part of the new college, growing from 85 pupils in 1829 to 500 in 1843 (Weinreb and Hibbert 447). Not that many of these boys rose to "the airier amplitudes of the professorial lecture-rooms" upstairs (Hearshaw 153): most either took wing for Oxford or Cambridge, or, especially after the introduction of a "modern" as well as classical section in January 1851, disappeared into what we might now call the business sector.

Still, wherever they went, many old King's boys did make names for themselves. One such old boy was Charles Dickens Jr, the author's eldest son, whose nomination form was completed by his father and signed by the philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts in her role as a governor of the school. The young Dickens appears to have had poor health for a while: in the March after his entry, there was a request for the return of a term's fees, on grounds of ill-health (Hearnshaw 193*). He went on to Eton, and while he did not reach the heights of his father, his Dictionary of London is a classic of its kind. Here he wrote a few lines about his old Alma Mater: "The upper school is divided into two sides: (1) Classics, mathematics, and general literature; (2) Modern instruction. There are also a middle and lower school which are preparatory to the upper divisions. The general age of admission is from 8 to 16 years."

King's College School and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

King's College School was perhaps most important in connection with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. The watercolourist John Sell Cotman (1782-1842) took up an appointment here as Drawing Master in 1834, retaining the position until his death in 1842. Cotman encouraged close observation and outdoor sketching, and two of his pupils, sons of the then Professor of Italian at King's, took these prescriptions very much to heart. They were Dante Gabriel Rossetti and his brother William, the future editor of The Germ. Dante Gabriel was there from 1837-1841, and William from 1837-1845. William later described Cotman as "the most interesting pedagogue of all . . . an alert, forceful-looking man, of modest stature, with a fine well-moulded face, which testified to an impulsive nature, somewhat worn and worried" (qtd in Moore).

Another artistically-inclined pupil who studied under Cotman, and to whom detail would also be vitally important, was the architect and designer William Burges. He was at King's from 1839-1843, where Rossetti (Dante Gabriel) remembered him as having been "excessively short-sighted" and having had "a chubby face like a cherub on a tombstone" (Mordaunt Crook). Burges's path in life was soon set, for his father, himself a prosperous civil engineer, gave him a copy of Pugin's newly-published Contrasts (1836) on his fourteenth birthday. Having stayed on into the "upper division," Burges studied engineering for a year before leaving to be articled to Edward Blore, the surveyor to Westminster Abbey, after which he worked for Matthew Digby Wyatt in the run-up to the Great Exhibition. He remained good friends with Rossetti, and indeed was friendly with most of the Pre-Raphaelites, with whose vision and aims he had much in common. Reginald Turnor describes him succinctly as "a complete medievalist in the French medium" and comments not only on his Gothic fantasies, best played out perhaps at his Melbury Road home in Kensington, but also on his "extreme scrupulosity" in planning (70). Cotman would have been proud of him.

Left: King's College School with its chapel-like façade by Sir Bannister Fletcher. 1891.

Right: Detail of the Façade. [Click on thumbnails for larger images.]

Yet another artist might have been pleased too. This was William Dyce (2206-64), who, after having been Director of the Government School of Design for the previous few years, was appointed Professor of Fine Arts at King's College in 1844. Along with William Bell Scott, Dyce was one of the two Scottish painters associated with the Pre-Raphaelite movement. He seems to have done little at the college, perhaps because of the big commissions he was getting around that time, but some of his architectural drawings are listed in the archives, and it is tempting to assume that Burges came up against him. Dyce's involvement with King's, however nominal, strengthens its claim to have provided the seedbed of Pre-Raphaelitism, for it was he who persuaded Ruskin.html "to look sympathetically at the Pre-Raphaelites' work" (Lambourne 238).

A later artist, Walter Sickert, had connections with both the founding colleges' schools. University College School lists him as an "Old Gower," but according to Wendy Baron it was from King's that he matriculated in 1878, before studying briefly at the Slade. In view of recent attempts to associate him with Jack the Ripper, it is particularly appropriate to imagine him studying in the "infernal regions" of King's!

As new roots sprouted for higher education in London, two girls' schools were also founded, Queen's College in Harley Street, and the school of the "Ladies' College" in Bedford Square. With the establishment in 1902 of the London Day Training College (later called the Institute of Education), the University of London's influence on school education was set to grow. On the other hand, as it evolved into a full teaching establishment, its secondary schools inevitably separated out from it. King's College School had already abandoned the vaults beneath its parent college and relocated to Wimbledon in 1897; University College School soon followed suit, moving out to Hampstead in 1907. As independent public schools, they both continue to produce eminent people in many walks of life. Girls will be admitted to University College School's Sixth Form from 2008.

* Confusingly, Hearnshaw suggests that this son was "presumably ... Frederick C. Dickens, who was in the fifth form at the time" (193). But Dickens did not have a son by this name. I think the son must have been the same Charles Jr who had only recently entered the school (see nomination paper). Who then was the older "Frederick C. Dickens"? While Dickens did take his feckless brother Fred under his wing for some time, he was in his twenties by now. Perhaps, despite the congruence of names, "Frederick C. Dickens" was unrelated.

Related Material

Sources

Baron, Wendy. "Sickert, Walter Richard, 1860-1942." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online ed. Viewed 3 May 2007.

Dickens, Charles Jr. Dickens's Dictionary of London: An Unconventional Handbook 1879. See " King's College School." Viewed 13 April 2007.

Harte, Negley, and John North. The World of University College, 1828-2004. 3rd ed. London: University College, 2004.

Lambourne, Lionel. Victorian Painting London and New York: Phaidon, pbk ed. 2003.

Miles, Frank and Graeme Cranch. King's College School: The First 150 Years. London: King's College School, 1979.

Moore, Andrew W. "Cotman, John Sell (1782-1842)." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online ed. Viewed 30 Jan. 2007.

Mordaunt Crook, J. "Burges, William (1827-1881)." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online ed. Viewed 13 April 2007.

Picard, Liza. Victorian London: The Life of a City 1840-1870. London: Phoenix, 2006.

Stray, Christopher. "Key, Thomas Hewitt, 1799-1875)." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online ed. Viewed 28 May 2007.

Turnor, Reginald. Nineteenth Century Architecture in Britain. London: Batsford, 1950.

"University College School website." Reviewed 13 April 2007.

Weinreb, Ben, and Christopher Hibbert, eds. span class="book">The London Encyclopaedia. London: Macmillan, 1992.

Created 2006

Last modified 26 July 2016