We are most grateful to be able to reproduce here material from Jane Rupert's edition of Letters of a Distinguished Physician from the Royal Tour of the British North American Colonies 1860 written by Henry Wentworth Acland. The whole edition is available on the web by clicking here.

r Henry Wentworth Acland, Regius Professor of Medicine at Oxford University, wrote twelve letters to his beloved wife, Sarah, while accompanying the Prince of Wales as physician during the royal tour. When the Prince of Wales laid the cornerstone for the parliament buildings in Ottawa, the new site for the capital of the united Canadas, now Ontario and Quebec, a federation with other provinces was already in the air. Seven years later, in 1867 Ottawa became instead the capital of the four federated provinces, Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia, that formed the nucleus of the Dominion of Canada.

While it might seem surprising today amid Quebec's recurrent claims to sovereignty, the Prince of Wales also received an enthusiastic welcome among the French-speaking populace in Quebec and Montreal. His reception reflects a culture conscious that it had been able to retain within the framework of British institutions the most profoundly important elements of its identity: its religion and language as well as French civil law and a franchise that extended broadly to a population comprised largely of small farmers, or habitants. The co-premier, George-Etienne Cartier, was both deeply aware of his inherited French culture and a monarchist. Although he had participated in the Rebellion of 1837 in protest against the fraudulent abuses of colonial officials, had been accused of treason, and had fled to the United States, he soon after became convinced that the welfare of the Canadas and the protection of French-Canadian identity within it could be achieved best through political means in a system derived from the British constitutional model.

The maturing political development of the British North American Colonies made their desire for federation one of the unofficial focuses of the royal tour. The Duke of Newcastle, who headed the royal party, was the secretary of state for the Colonies, responsible not only for the appointment of governors in British colonies but for their forms of government. It was to the Duke that colonial requests and grievances were addressed. During the course of the tour, he had ample scope for conversation on matters of colonial concern including the subject of confederation. In the capitals of the Atlantic colonies he met lieutenant governors and executive councils. Then, after entering the waters of the Canadas, the travelling party included Sir Edmund Head, the governor general, and John A. Macdonald and George-Etienne Cartier who within a few years were to be key figures in the confederation of four of the colonies which formed the nucleus of the Dominion of Canada.

The opinion on confederation of Sir Edmund Head, colonial administrator in the British North American Colonies for sixteen years, was already well known. He had long been an eloquent advocate of a federation of self-governing colonies allied by ties of affection to Britain. In 1851, as lieutenant governor of New Brunswick he wrote of his vision of a new nation extending from sea to sea in which the forms and the substance of the British constitution should come to maturity. When Responsible Government, based on Britain's constitutional monarchy, was introduced in New Brunswick, he nurtured the governor's and executive council's responsibility to the elected assembly and encouraged self-government through inter-colonial free trade between New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. Then, as governor general of the Canadas, even as he dealt with the difficulties of an uneasy relation between two different cultures united under a single legislature, he recognized that the two Canadas were linked by their same essential interests and their common geography with the St Lawrence River in the lower province as the outlet to the ocean for the upper province's vast system of inland lakes.

At the time of the tour, political leaders within the united Canadas had also opened the way towards confederation. John A. Macdonald, who just seven years later became the first prime minister of the federated colonies, and his co-premier, George-Etienne Cartier, had already effected a definitive break in the contentious political climate of the united Canadas through their political cooperation. Following the direction already indicated by others, in 1856 these conservative leaders in the two provinces made common cause. The beginning of strong party government not only circumvented ethnic division between the colonies but opened the way for a resolution of political tensions through electoral change and enabled political coordination for a larger federated union.

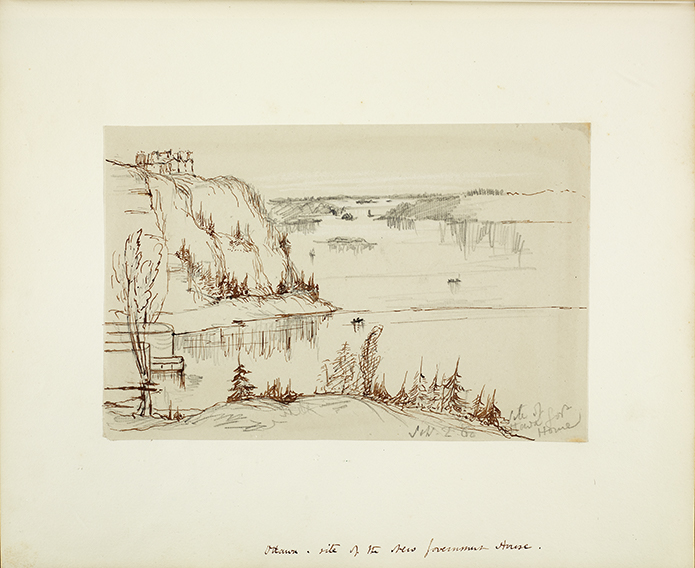

"Ottawa - site of the new Government House. Sept 2. 60."

On the left, below the partially-built parliament buildings for the united Canadas, is the entrance to the Rideau Canal, part of a system of British military defenses built after the attack by the United States on the North American colonies during the War of 1812-14. To avoid rivalries among the cities that had served as capitals since the union of the Canadas in 1841, Queen Victoria followed Edmund Head's advice in designating Ottawa as the permanent site for the capital in 1857. Not only was Ottawa conveniently located on the border between the two provinces but it was also placed at a strategic distance from the American border and potential American aggressions. The Gothic Revival style of the three blocks under construction since 1859 had been chosen over neo-classical proposals then identified with American republicanism. The tower of the Centre Block, destroyed by fire in 1916, was similar to the tower of the Oxford University Museum. The buildings were completed in 1866, four years later than anticipated and four times more costly than projected. In the following year, they became the parliamentary home of the four provinces that comprised the newly federated country.

In his letter to Sarah, Acland wrote: - We stood on the heights overhanging the Ottawa on the bare ground, whence the future Canadian Parliament will look from their windows over the precipice upon the deep blue and brown waters and on the wide falls of the Ottawa - and on the huge mills & the timber rafts - and the ever extended pine forests - we went to breakfast - ate woodcocks or grouse - and afterwards had half an hour before we put on our uniforms - and went to lay the stone of the future Parliament - there was deposited a huge white marble block or corner stone of the Tower something like an ornate and Gigantic Oxford Museum - in two years to be completed.

Material relating to Dr Acland

- Dr Henry Wentworth Acland: A Brief Biography

- The Indigenous People of Canada

- The Timber Industry in Canada

- Victoria Bridge, Montreal

Related Material (general)

- A Brief Timeline of Canadian Political History

- The Government of Canada

- Other sites for Canadian Politics and Government

Bibliography

Acland, Henry Wentworth. "Introduction" and "Letter 9: Ottawa" in Letters of a Distinguished Physician from the Royal Tour of the British North American Colonies 1860. ed. Jane Rupert, web janerupert.ca

Bonenfant, J.-C. "Cartier, Sir George-Etienne." In Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol.10. University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003. http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cartier_george_etienne_10E.html. Web. 16 April 2013).

Coates, Colin M. "French Canadian Ambivalence to the British Empire." In Canada and the British Empire. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Gibson, James A. "Head, Sir Edmund Walker." In Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9. University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003. Http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/head_edmund_walker_9E.html (accessed June 10, 2014).

Greer, Allan, and Ian Radforth, eds. Colonial Leviathan: State Formation in Mid-Nineteenth-Century Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1992.

Johnson, J.K., and P.B. Waite. "Macdonald, Sir John Alexander." In Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12. University of Toronto/Université Laval. Http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/macdonald_john_alexander_12E.html. Web. 20 April 2013).

McCalla, Douglas. "Economy and Empire: Britain and Canadian Development, 1783-1971." In Canada and the British Empire. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Created 2 July 2023