In transcribing the following paragraphs from the Internet Archive online version of The Imperial Gazetteer’s entry on British India — modern South Asia — I have expanded the divided the long entry into separate documents, expanded abbreviations for easier reading, and added paragraphing and links to material in the Victorian Web. The charts are in the original. This discussion of British India has particular importance because it immediately precedes the 1857 Mutiny and the subsequent major shift in its status as it came under the direct control of the British government rather than that of the East India Company, a private company.— George P. Landow]

Roads

The inland trade of India is greatly impeded by the want of internal communication. The grand trunk road from Calcutta to Benares and Delhi, on the latter portion of which the bridges over the rivers have only been recently made; a good road from Pauwelly, opposite Bombay, to Poonah; others from Bombay to Ahmednuggur, into Candeish, through the Concan district, on the Malabar coast, and for a part of the way, and to Jubbalpoor in Central India; one from Mirzapoor, on the Ganges, to Jubbalpoor and Nagpoor; and one from Masulipatam to Hyderabad, constituted the only lines of route, worthy of especial notice, as having been constructed before 1850, when several good and extensive roads were made in the Punjab, between Lahore, Putankote, and Mooltan, &c.; and one was begun between Lahore and Peshawur.

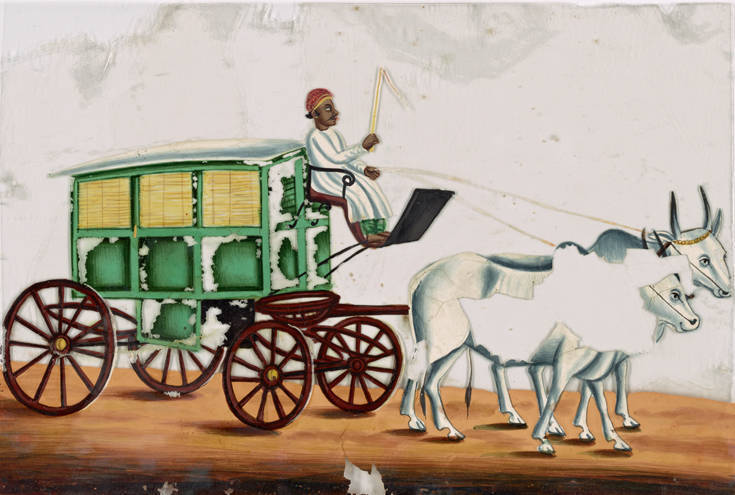

Left: Green wagon with yellow windows, driver in white robe, pulled by 2 white oxen. 100 x 148 mm. Right: Aristocrat in green palanquin, accompanied by four bearers and a servant. 99 x 148 mm. Both Watercolor gouache on mica, 1780-1858, from the Collection New York Public Library Digital Collections nos. b13976376. Click on images to enlarge them.

Excepting the foregoing, all of which have been formed chiefly within the last century, few public ways exist that are better than mere tracks, along which rude cars can be drawn, or oxen driven. Pack-bullocks of small size, carrying a load of about 240 pounds, are used for the con veyance of many kinds of goods; camels, for the same pur pose, toward the west. frontiers; and, in the Himalaya, goats and sheep. Elsewhere, most of the merchandize is conveyed on the backs of brinjarries, a caste of Hindoos whose business is that of carriers.

Left: Oxen-drawn green and pink carriage with female passenger, driver and servant. 110 x 147 mm. Right: Horse-drawn two-wheeled carriage with blue wheels. 107 x 144 mm. Both Watercolor gouache on mica, 1780-1858, from the Collection New York Public Library Digital Collections nos. b13976376. Click on images to enlarge them.

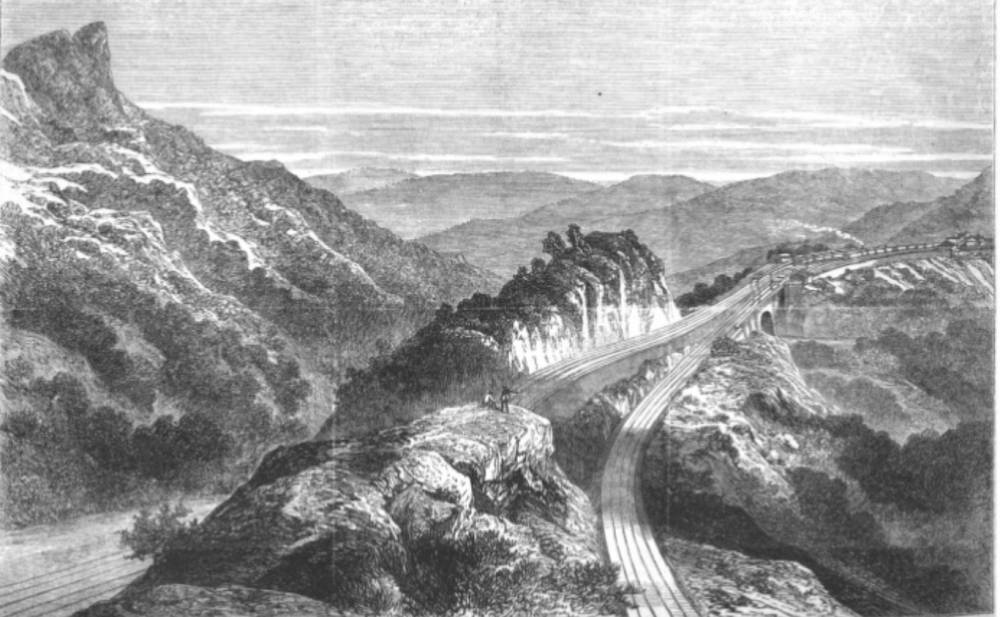

The impediment to prosperity on account of the absence of roads, will be made strikingly apparent by the fact that, in 1823, while grain in Candeish was plentiful enough to be sold at from 6s. to 8s. a quarter, in Aurungabad, not 100 miles distant, it was 34s.; and at Poonah, perhaps 150 miles farther, from 64s. to 70s. a quarter; and yet, for the want of routes on which to convey it, no attempt could be made to equalize the price of corn in these localities. It is stated that, during the ten years from 1836 to 1846, the sum of £1,446,400 was spent by the East India Company in the formation of roads, buildings, bridges, tanks, and canals in India, exclusive of repairs. The railways projected or in progress in all the three presidencies, when completed, will remove many of the difficulties as to roads complained of, and tend greatly to the development of the great natural riches of India.

An Indian Railway Fifteen Years after the Gazetteer: The Reversing Station, Bhore Ghaut, on the Great India Peninsula Railway. From the 1869 Illustrated London News.

The Ganges canal

One of the most magnificent and the most useful of tho works ever undertaken by the British Government in India, is the Ganges canal, now in progress of execution in the Doab, between the Ganges and Jumna. It commences at Hurdwar, and is to extend for a distance of 180 miles, to near Alighur, where it will diverge into two channels, one, 170 miles in length, running to the Ganges, at Cawnpoor; and the other, 165 miles in length, to the Jumna, near Humeerpoor, 40 miles west. by north Futtehpoor. Branches, with an aggregate extent of 250 miles, will proceed to Futtehghur, and Coel; the total length being 765 miles.

This canal, which will be navigable through out, is intended also to irrigate a tract of 8400 sq. miles; and it is estimated that the increase of land revenue in the country through which it is carried will be 350,000 per annum; and, in addition, that about 160,000 will be annually derived from it by the sale of water. Very extensive masonry works are requisite for the Ganges canal. A considerable portion of the undertaking is already completed; and, of somewhat more than £1,500,000, which it is estimated will be the total cost, £634,000 had been spent on its construction at the close of 1850. A large canal, estimated to cost half a million sterling, has been commenced in the Punjab. Both the Ganges and the Indus are now navigated by steam-vessels, the former river by strong and very buoyant iron boats.

Sources of this section: Mill’s History of British India; Prinsep’s Bengal and Agra Gazetteer, 1841; M’Gregor’s Report on British India 1848; Stocqueler’s Handbook for India; Board of Trade Report, 1849; Papers on Imports and Exports, 1846; Reports on Sugar and Coffee Planting, and on the, Growth of Cotton in India; Acts of the Government of India; Calcutta Review, 1850-51.)

Bibliography

Blackie, Walker Graham. The Imperial Gazetteer: A General Dictionary of Geography, Physical, Political, Statistical and Descriptive. 4 vols. London: Blackie & Son, 1856. Internet Archive. Inline version of a copy in the University of California Library. Web. 7 November 2018.

Last modified 7 December 2018