As a writer and photographer she recounted her remarkable experiences to a devoted readership; whether climbing volcanoes or washing her photographic plates in the waters of the Yangtze. — Rita Gardner

A perceptive and caring traveller

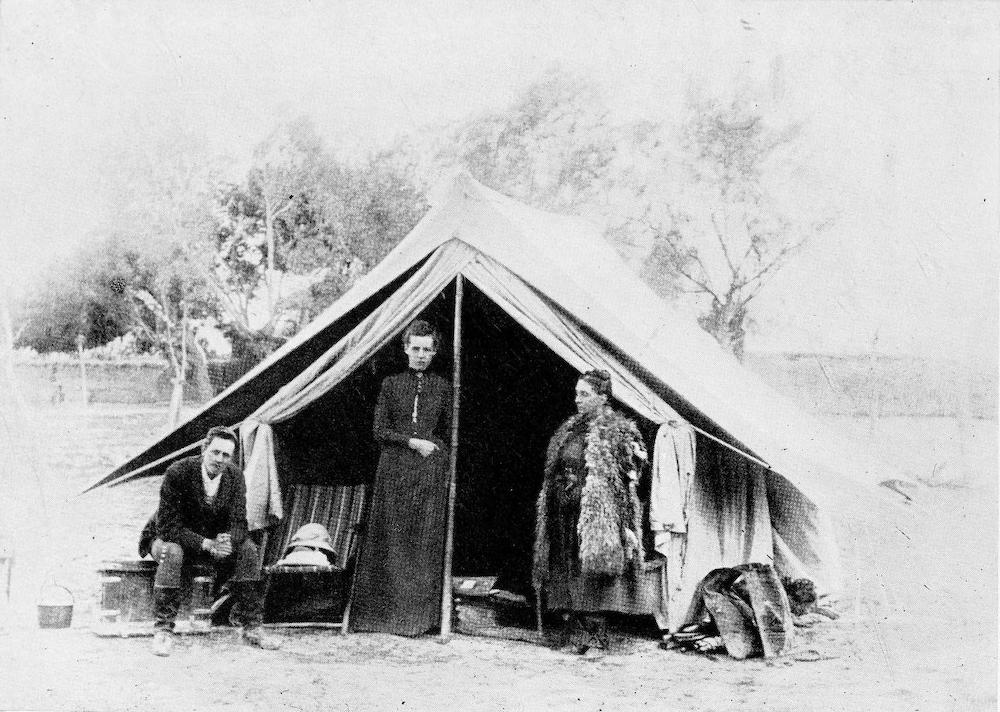

Mrs Bishop's Tent among the Bakhtiari Lurs, with companions who accompanied her as far as the frontier of the Bakhtiari country. Isabella Bird is on the right. Source: Stoddart, facing p. 228.

In the preface to her biography, Stoddart writes admiringly about her subject's qualities as a traveller:

As a traveller Mrs. Bishop’s outstanding merit is, that she nearly always conquered her territories alone; that she faced the wilderness almost single-handed; that she observed and recorded without companionship. She suffered no toil to impede her, no study to repel her. She triumphed over her own limitations of health and strength as over the dangers of the road. Nor did she ever lose, in numberless rough vicissitudes, in intercourse with untutored peoples, or in the strenuous dominance which she was repeatedly compelled to exercise, her womanly graces of tranquil manner, gentle voice, reasonable persuasiveness. Wherever she found her servants — whether coolies, mule-drivers, soldiers, or personal attendants — she secured their devotion. The exceptions were very rare, and prove the rule.

Wherever she went, she gave freely the skilled help with which her training had furnished her, and her journeys were as much opportunities for healing, nursing, and teaching, as for incident and adventure. She longed to serve every human being with whom she came in contact. [Stoddart vi]

Her obituary in the American Geographical Society's bulletin also praised her for being "an accurate observer, [who] took a wide interest in natural phenomena, was an enthusiastic botanist, and had some knowledge of chemistry, all of which helped to give value to her studies of nature and peoples." It adds, quite significantly, that "[s]he usually chose as the scenes of her travels those regions that were coming into public notice, and thus her accurate and careful descriptions had a timely and practical interest."

Nowadays, we may admire her confident handling of those who assisted her, while feeling some reservations about her easy assumption of superiority, and her trust in "the political wisdom and absolutely constitutional rule of Queen Victoria" — as well as her evident satisfaction with the advances already made by British women in "art, literature, music, and other things" (Journeys in Persia and Kurdistan, 265). There is a certain complacency here. It was understandable: much of what she saw bolstered her trust in her own values, and her feeling that if they were brought to bear on others, some of their problems would be remedied. Yet she was also alive to the possibilities that life could be "beautiful and pure" even in the most unpromising context, and even when lived by someone of a different creed (Journeys in Persia and Kurdistan, 262). And, as a woman following untrodden or rarely trodden paths, she asserted an independence far in advance of current gender expectations.

Isabella Bird as a writer

Accuracy alone is not enough to make a writer popular. The success of Isabella's nine travelogues also owed much to her engaging style and the lively, personal way in which she reports on her experiences. Here she is in Korea, for example, making her way down a river in her sampan:

Abrupt turns, long rapids full of jagged rocks, long stretches of deep, still water, abounding in fish, narrow gorges walled in by terraces of basalt, lateral ravines disclosing fine snow-streaked peaks, succeeded each other, the shores becoming less and less peopled, while the parallel valleys abounded in fairly well-to-do villages. Just below a longhand dangerous rapid we stopped to dine, and though the place seemed quite solitary, a crowd soon gathered, and sat on the adjacent stones talking noisily, trying to get into the boat, lifting the mats, discussing whether it were polite to watch people at dinner, some taking one side and some another, those who were half tipsy taking the affirmative. Some said that they had got news from several miles below that this great sight was coming up the river, and it was a shame to deprive them of it by keeping the curtains down. After a good deal of obstreperousness, mainly the result of wine, a man over-balanced himself and fell into the river, which raised a laugh, and then they followed us good-naturedly up the rapid, one man helping to track, and asking as his reward that his wife might see me, on which I exhibited myself on the bow of the boat. [Korea and Her Neighbours I: 107-8]

The dangers of the journey are underplayed, the delights of unusual scenery fully explored, the human interest never lacking.

A Dervish. Source: Journeys in Persia I: 356.

Her accounts of wedding ceremonies in Japan and India, for example, are not only closely observed but convey the atmosphere and impact on the attendee as well. The two occasions could hardly have been more different. In the Japanese one, tedium soon sets in because of the predominance of etiquette, in a performance "conducted in melancholy silence ... the young bride, with her whitened face and painted lips, looked and moved like an automaton" (Unbeaten Tracks in Japan I: 330). In Persia, on the other hand, a Bakhtiari marriage lasts three days or more, almost overwhelming her with its rambunctiousness: "The noise at this time is ceaseless. Drums, tom-toms, reeds, whistles, and a sort of bagpipe are all in requisition..." (Journeys in Persia I: 356). After this one, she retires to her tent, still pursued by the noise, and eventually peeps out to find five rows of people seated around it, waiting for medical attention, "chiefly eye-lotion, quinine, and cough mixtures." She cannot help adding, in a way that reveals both her weariness and her motivation, "These daily assemblages of 'patients' are most fatiguing. The satisfaction is that some 'lame dogs' are 'helped over stiles,' and that some prejudice against Christians is removed" (Journeys in Persia I: 357).

As in the description of the Japanese bride as looking like an automaton, there is often a touch of humour about her descriptions, which is not dated at all. Persian dervishes, for example, grate on her ideas of serving others, and her moral standards generally: they seem to "hold universally the sanctity of idleness, and the duty of being supported by the community" — and to have "many vices, among the least of which are hazy ideas as to mine and thine" (Journeys in Persia I: 237).

It is no surprise, then, that her travel books entitle this author to a place in The Oxford Guide to British Women Writers and other such compendiums, as well as in books more specifically on explorers. The Oxford Guide points to "her reputation as one of the outstanding travel writers of her day" (Shattock 44). That being said, readers today might find it hard to accept that most of the peoples she encounters were really "in sore need of ameliorating influences, and of being lifted up to that type of highest manliness and womanliness which constitutes the Christian ideal." On this particular occasion she is speaking about Japan, and to her credit adds, perhaps inadvertently setting the balance a little straighter, "If they were less courteous and kindly one would be less painfully exercised about their condition" (Unbeaten Tracks in Japan I: 192-93).

Isabella Bird as a photographer

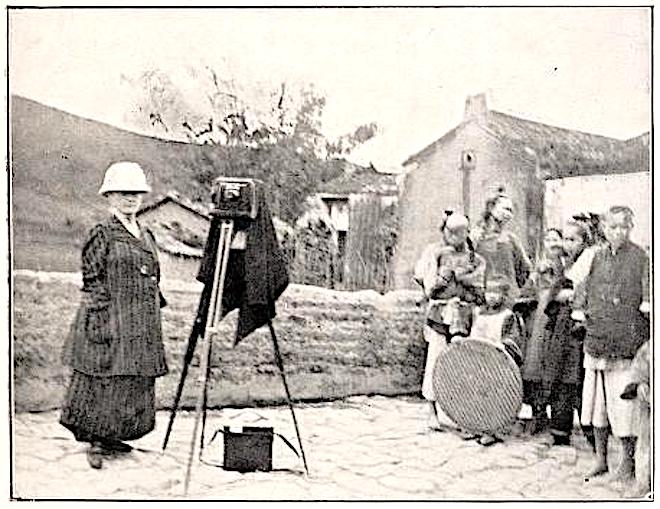

Snapshot taken of Mrs Bishop at Satow by Mr Mackenzie. Source: Stoddart, facing p. 298.

Isabella Bird is also important as a photographer. The National Library of Scotland has a large holding of her travel photographs, over 140 them, showing "people, landscapes and buildings in China, Japan, Korea, Persia and Morocco." Along with them are some of her "published title pages, illustrations, itineraries and maps, and several of her letters discussing her passion for photography and the places she was travelling in" ("Isabella Bird's Travel Photographs..."). Many if not all of the photographs appear in the books themselves, but it is still useful to see these materials together. They point to curiosity, empathy, and an eye for a good composition which makes her later works even more valuable.

Female Beggar in Mat Hut in Hankow, now a part of Wuhan City.

Source: The Yangtse Valley and Beyond, 78.

A doctor's wife in Hangchow remembered her great enthusiasm for photography — how she yielded "to the fascination and excitement of developing her plates and toning her prints at night, midnight, and even early morning. She gave me my first lesson in photography, and was as pleased as could be to teach me how to develop, which she told me in the 'dark room' was the most interesting part of it all" (qtd. in Stoddart 298). A missionary with whom she stayed briefly in Shao Hsing also noted not only her independent and fearless spirit, but her determination to photograph as many of the sights as she could:

I introduced to her notice some new features of interest daily, and her stock of photographic plates soon came to an end in her endeavour to secure lasting pictures of the ancient buildings and monuments with which our city abounds.... though generally very much exhausted when the close of the day came, she appeared to be tireless so long as anything of interest remained to claim her attention.... She generally breakfasted in her room, and rose late, retiring at night about 11 p.m. apparently quite worn out; but she always had sufficient reserve of strength to occupy an extra hour or two in the development of her photographs. She carried a folding-chair specially constructed to support her back when she sat.... 299-300Her absolute unconsciousness of fear was a remarkable characteristic; and even in remote places, where large crowds assembled to witness her photographic performances, she never seemed in the least to realise the possibility of danger. Had she done so, she would have missed a great deal of what she saw and learned..... even in the face of the largest and noisiest crowds, Mrs. Bishop proceeded with her photography and her observations as calmly as if she were inspecting some of the Chinese exhibits in the British Museum. [Stoddart 299-300]

In this way she recorded not only her travels, and the places and customs she encountered, but also the individual people whom she saw, with their expressions, costumes and settings. Whether mandarin or beggar-woman, all held her attention, and all are presented to us memorably alongside her descriptions. Photography, however, was no mere adjunct to the written word. Although she was not one of the earliest practitioners, once she had become involved with this medium, she was captivated by it, confessing in a letter to John Murray IV, in 1897, "nothing ever took such a hold on me as Photography has done. If I felt sure to follow my inclination I should give my whole time to it" (qtd. by Gardner 7). As it was, even without devoting all her time to it, she made her mark as a photographer as well as a travel-writer.

Links to related material

Bibliography

Bishop, Mrs. (Isabella L. Bird). Journeys in Persia and Kurdistan: including a summer visit to the Upper Karun Region and a visit to the Nestorian Reyahs. I. London: John Murray, 1891. Internet Archive. Contributed by an unknown library. Web. 22 August 2022.

_____. Korea and Her Neighbours I. London: John Murray, 1905. Internet Archive. Contributed by the Digital Library of India; JaiGyan. Web. 22 August 2022.

_____. Unbeaten Tracks in Japan: An account of travels on horseback in the interior.... 2 vols. bound together. New York: Putnam's, 1880. Internet Archive. Contributed by Duke University Libraries. Web. 22 August 2022.

_____. The Yangtze Valley and Beyond: An account of journeys in China, Chiefly in the province of SzeChuan and among the Man-tze of the Somo territory. London: John Murray, 1899. Internet Archive. Contributed by Robarts Library, University of Toronto. Web. 22 August 2022.

Gardner, Rita. Foreword to Ireland. 7.

Ireland, Deborah. Isabella Bird: A Photographic Journal of Travels through China, 1894-1896. Lewes, E. Sussex: Ammonite Press/Royal Geographical Society, 2015. (This has an excellent chronology, pp. 228-29, and bibliography, pp. 230-31.)

"Isabella Bird's Travel Photographs." National Library of Scotland

Middleton, Dorothy. "Bishop [née Bird], Isabella Lucy (1831–1904), traveller." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online edition. Web. 22 August 2022.

Shattock, Joanne. The Oxford Guide to British Women Writers. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Stoddart, Anna M. The Life of Isabella Bird, Mrs Bishop. Internet Archive, Contributed by the Wellcome Institute. Web. 22 August 2022.

Created 22 August 2022