All illustrations except the first come from our own website. Click on them for more information about them, and to see larger versions of them. — JB

It may come as a surprise to learn that the late Victorian and Edwardian periods, the time of the Scramble for Africa and of the Empire on which the sun never set, the age of Hardy, Kipling and Bernard Shaw, the era of Burne-Jones and Sickert, can be considered one of decadence. Nowhere does Simon Heffer explicitly try to justify the choice of his title, but while reading his book, one comes across the word and its synonyms (decline, decay, deterioration…) more or less regularly, depending on the chapters.

Obviously, the years envisaged in the book cannot have been one of systematic decline in all aspects; neither should "decadence" be taken in the sense it had in art history, in relation with the Decadent school of literature, which applies more specifically to the Naughty Nineties. Starting with the upper classes, Simon Heffer can easily show that the last decades of the nineteenth century and the first fifteen years of the twentieth century were a period of financial decline; examining the various scandals in which King Edward VII was involved may also contribute to an impression of degeneracy at the summit of the social hierarchy, even though his successor gave a more dignified image of royalty. (Heffer seems to have much less to say about Queen Victoria in her last years, apart from her heartfelt opposition to Gladstone and Liberal politicians in general.) Logically enough, the notion of decadence is almost entirely lacking from the second chapter, devoted to the ascension of the middle class, whose "strong moral code . . . acted as a bulwark against the further spread of decadence, whatever the depravities of the upper and working classes" (41).

A "rearguard action": William Goscombe John's figure of The Boy Scout, 1910.

Reading lines such as these, one might think that the word does not reflect the opinion of the author, but what the Late Victorians and Edwardians thought of themselves. The fear of degeneracy was very much in the air since Max Nordau published his famous book Entartung in 1892-93, and several attempts were made to try and counter a process which some considered inevitable: Baden-Powell's scouts were supposed to become "a rearguard action against decadence" (490), the Girl Guides later joining in the same fight. On the other hand, the very fact that the British were then pleased with themselves is shown by Heffer as a result of their own country's "falling behind": "a decadence that bred complacency about Britain's future, and its place in the world" (433). It should be recalled that prophets of decline already existed before 1880, and imagining a Britain that would no longer be great had been for some time a sort of national sport. In 1856, taking up Macaulay's gloomy prophecy, the still relatively unknown Anthony Trollope wrote The New Zealander, in which he considered the possibility that his country might eventually decline and fall just like the Roman Empire, a topic which Prime Minister Arthur Balfour took up in a conference he delivered in Cambridge in 1908.

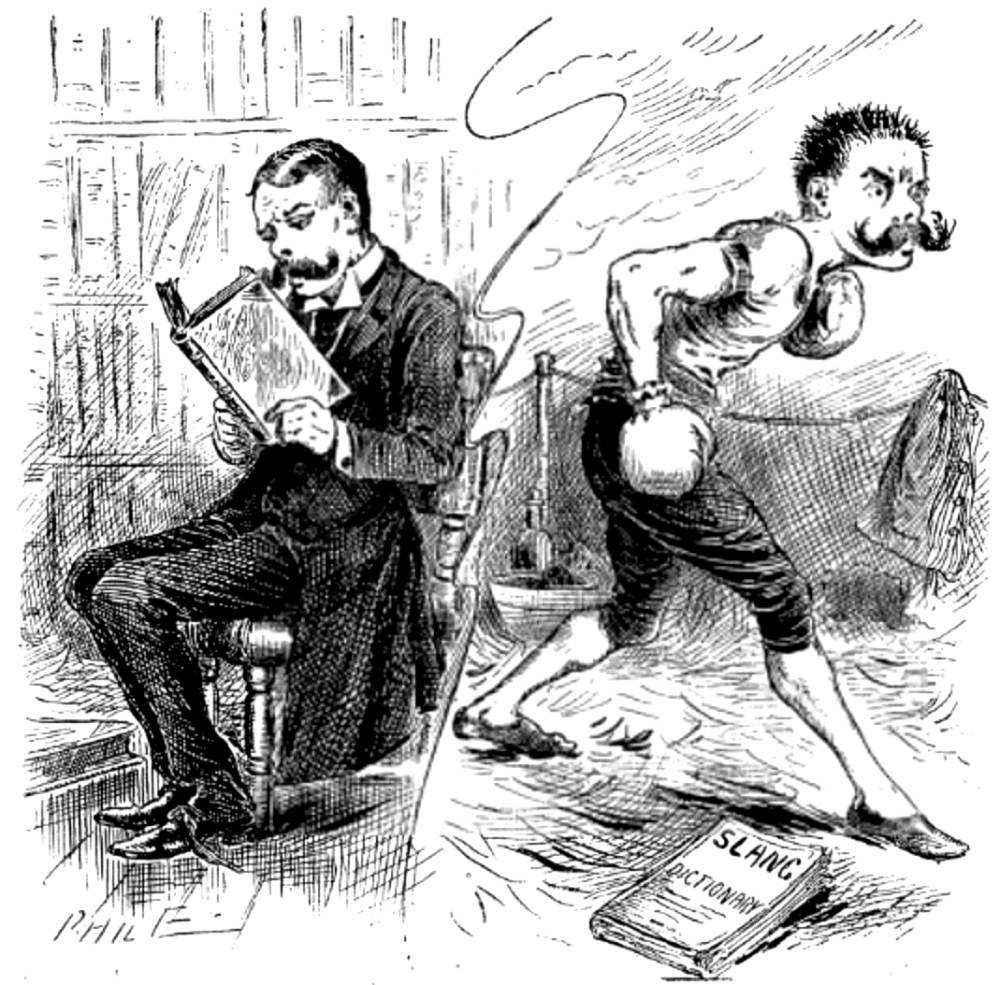

Posing: "Mr Dorrit's Transformation" — Harry Furniss's illustration

of 1910 for Dickens's Little Dorrit.

It appears that this perception of a decaying nation is Heffer's own, probably because he compares the period going from Gladstone's second administration to the start of the First World War with the immediately preceding era, which he described in a book entitled High Minds devoted to the years 1838-1880. After the heights reached the Early and Middle Victorian age, the following decades appear as a kind of nadir of civilisation:

The obsession with show; the importance of the pose; the decline of the spiritual and the rise of the material; an undue concentration of wealth among a privileged few, many of whose new recruits lacked the philanthropic impulse of an earlier generation – all these provided the stuff of the moral, intellectual and industrial decline that made this an age of decadence. [30]

It is more specifically in relation with territorial matters that Heffer seems to perceive the decadence of Great Britain, notably colonial defeats and the first signs of the Irish rebellion. He considers that "the very celebration of [the "glorious failure" of Scott's expedition to the South Pole] fits in appropriately with the values of an age of decadence" (494), and he takes "Britain's inability to control what was happening in Ireland" (823) as emblematic of the decadence of British power, concluding his analysis on those words: "A nation so recently not just great, but the greatest power the world had ever known, sustained in its greatness by a rule of law and parliamentary democracy, had begun its decay" (824). One should therefore expect an even darker vision of the country if a third volume is to come, depicting the middle decades of the twentieth century.

Another striking characteristic of the volume is its literary quality. Indeed, Heffer is a master story-teller, who manages to never lose his readers even in the most intricate narratives, of which there are many in his book. His writing can captivate by focusing on fascinating individuals, like Charles Gordon, "a celebrity soldier with traits of the Renaissance man" (221), or W.T. Stead, "the father of . . . tabloid journalism" (398) who had "made a habit of engaging in very twentieth-century practices" (225). But "literary" also takes another meaning in The Age of Decadence, in which a quantity of published fictions feature among primary sources, for their historical value, reflecting the mindset of an era. This particularity can be noticed right from the first chapters: while "The Decline of the Pallisers" refers to Plantagenet Palliser, the hero of Trollope's "political novels," its pendant, "The Rise of the Pooters" is a slightly more obscure allusion to George and Weedon Grossmith's Diary of a Nobody (1888-89), a novel about a London clerk named Charles Pooter. Heffer uses Galsworthy's depictions of the moneyed classes in his novels or of the working class in his play Strife, as well as the tales of provincial lower middle class written by Arnold Bennet, whose name and most famous titles very often recur between pages 120 and 537 (sometimes without specifying that Edwin Clayhanger is a character in a novel, as on page 254); Forster's Howards End is even more often quoted.

Some of the facinating individuals that Heffer discusses. Left to right: (a) Statue of Charles Gordon on the Embankment, London, by Hamo Thornycroft, 1887-8. (b) Memorial to W.T. Stead, also on the Embankment, by George Frampton, 1920. (c) H.G. Wells and G.B. Shaw in conversation, as sketched by E. Harries, n.d.

Heffer also relies on the way of life of some writers in order to reflect the evolution of mentalities, and the resistance to modern practices (as opposed to modern ideas, which gained readier acceptance). H.G. Wells is a case in point, whose philandering assumed the name of free love; in Ann Veronica (1909), he did not simply tell the story of a pretty and intelligent young woman attracted by suffragism: the independent heroine renounces her freedom when she is subjugated by a biology teacher, just as Wells, a biology teacher, had subjugated his pupil Amy Robbins, whom he married after divorcing his first wife and who tolerated his numerous love affairs. In spite of this reliance on writers and their creations, Heffer does not grant too much attention to a figure who remains one of the symbols of fin-de-siècle decadence. The emotion resulting from Oscar Wilde's now famous trial was apparently far less clamorous than that of the Cleveland Street scandal which occurred a few years earlier: in 1889, a male brothel was discovered by the police, its most prominent client being Lord Arthur Somerset, equerry to the Prince of Wales. Even though the accusations against Prince Eddy, one of the Queen's grandsons, were never substantiated, some Radical Liberals, including Henry Labouchère, were convinced that the government had conspired to cover up the affair.

Not regarded, positively detested, or vindicated. Left to right: (a) Portrait photograph of Oscar Wilde, by Sarony, in 1883. (b) Cartoon showing two sides to Randolph Churchill, in Fun magazine, 1885. (b) Charles Bradlaugh, in an etching by William Strang, c. 1890.

Heffer makes no effort to hide his preferences and reserves his most scathing irony for his pet detestations. Lord Randolph Churchill (1849-1895), Sir Winston's father, once a Leader of the Conservative party, is one of them. We read about this "controversial figure" whose speeches tended to be "long on jokes and short analysis" (63); just after reporting Churchill's denunciation of Charles Bradlaugh as a dangerously amoral anarchist because he refused to take the Oath of Allegiance when being sworn in, Heffer ends his paragraph on this efficiently simple conclusion: "It remains uncertain whether Churchill himself succumbed to a brain tumour, or to tertiary syphilis as a consequence of familiarity with prostitutes" (341). As for Virginia Woolf, whom he often calls "Mrs Woolf," and "whose talent and originality" he considers were far exceeded by those of James Joyce (533), he repeatedly accuses her of downright snobbery in her opposition to Arnold Bennett. It is perhaps due to Mr Heffer's little interest in modernism that, though he does mention Wyndham Lewis once (532), it is only as an opponent of Roger Fry rather than as the leader of the Vorticist movement and editor of the magazine Blast whose first issue was published in July 1914. Though dating from a few years before the beginning of the period considered, a reference to Whistler's "pot of paint in the public's face" exhibited at the Grosvenor Gallery in 1877 might have shown that London was not totally foreign to the latest innovations in art.

Before the start of the First World War, Britain had enlarged the suffrage with the Third Reform Act and would grant the vote to women immediately after the conflict. Its population enjoyed a much better standard of living than fifty years before. Though "an accomplished adulterer and glutton" (87), the Prince of Wales had made Jews acceptable in Royal society. And yet, "beneath the façade of swagger there was often a philistinism and arrogance that had yet to work themselves out" (20). It was the best of times, it was the worst of times….

Bibliography

[Book under review] Heffer, Simon. The Age of Decadence, A History of Britain: 1880-1914. New York, London: Pegasus Books. First published 2018, new edition 2021. 900 pages, 50 colour illustrations. ISBN: 9781643136707.

Created 20 August 2023