The following text comes from the program for the 2007 Bard College concert series and symposium entitled Elgar and His World, which was organized by Leon Botstein, Christopher H. Gibbs, and Robert Martin, Artistic Directors, Irene Zedlacher, Executive Director, and Byron Adams, Scholar in Residence 2007. Readers may wish to consult the festival site for additional information about this and past festivals and related publications, including Elgar and His World, ed. Byron Adams, which Princeton University Press published in 2007.

"I am self-taught in the matter of harmony, counterpoint, form, and, in short the whole of

the 'mystery' of music." In the interview in which this statement appeared, Elgar remarked

pointedly,"When I resolved to become a composer and found that the exigencies of life would

prevent me from getting any tuition, the only thing to do was to teach myself. . . . I read

everything, played everything and heard everything I possibly could." Aside from some early

piano lessons, what he could pick up from the books found in his father's music shop in

Worcester, and violin lessons with the Hungarian virtuoso Adolphe Pollitzer, Elgar amassed

his dazzling technique largely on his own initiative. In his ambitions, he had the support of his

mother, Ann, who, though the daughter of illiterate farm laborers, was a dedicated reader

who wrote poetry. Elgar's father, of whom the composer later recalled that he "never did a

stroke of work in his life,"was less than encouraging. One of Elgar's boyhood friends recalled

that the composer's father not only declined to acknowledge that there was "an exceptionally

gifted boy in the family, but even that [his son] was moderately clever at music." Born

into a working-class family who rose into the lower-middle class through trade, Elgar was a

classic example of an autodidact determined to succeed through hard work, self-education,

and talent.

"I am self-taught in the matter of harmony, counterpoint, form, and, in short the whole of

the 'mystery' of music." In the interview in which this statement appeared, Elgar remarked

pointedly,"When I resolved to become a composer and found that the exigencies of life would

prevent me from getting any tuition, the only thing to do was to teach myself. . . . I read

everything, played everything and heard everything I possibly could." Aside from some early

piano lessons, what he could pick up from the books found in his father's music shop in

Worcester, and violin lessons with the Hungarian virtuoso Adolphe Pollitzer, Elgar amassed

his dazzling technique largely on his own initiative. In his ambitions, he had the support of his

mother, Ann, who, though the daughter of illiterate farm laborers, was a dedicated reader

who wrote poetry. Elgar's father, of whom the composer later recalled that he "never did a

stroke of work in his life,"was less than encouraging. One of Elgar's boyhood friends recalled

that the composer's father not only declined to acknowledge that there was "an exceptionally

gifted boy in the family, but even that [his son] was moderately clever at music." Born

into a working-class family who rose into the lower-middle class through trade, Elgar was a

classic example of an autodidact determined to succeed through hard work, self-education,

and talent.

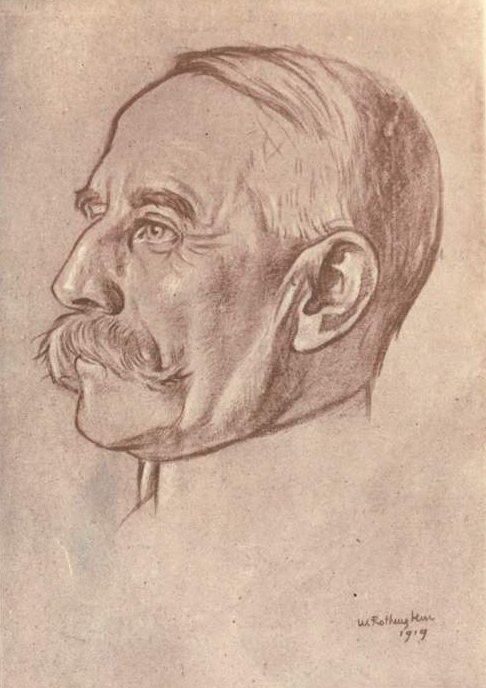

Sir Edgar Elgar, O. M. by William Rothenstein. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

To trace Elgar's rise from provincial tentativeness to international mastery, the only possible point of departure is the music that he composed during his youth in Worcester. While Elgar's earliest efforts at composition were jejune parlor songs and choral pieces predicated on preexisting music by Beethoven and others, he quickly managed to create some modest but attractive pieces, including the polkas, marches, and quadrilles he wrote to entertain the inmates of the local insane asylum. Growing up in a small city where talented musicians were relatively scarce, the ambitious young Elgar garnered many opportunities to compose, perform, and conduct, thus amassing a matchless fund of practical experience.

The Harmony Music No. 4, subtitled "The Farmyard" (without, thankfully, directly portraying the denizens of such a locale), is the most successful of the woodwind quintets that Elgar composed in his early twenties. With the series title having been translated from the German Harmoniemusik, these works were scored for the unusual combination of two flutes, oboe, clarinet, and bassoon. Written for an ensemble that consisted of Elgar — who played the bassoon — and his brother Frank, along with some of their musical friends, this unpretentious piece reflects the young composer's careful study of Mozart in its neatly delineated sonata form.

The Sursum corda, Op. 11, for strings, brass, timpani, and organ, was written hurriedly in 1894 for the royal visit of the Duke of York (later King George V) to the Anglican Cathedral in Worcester. Elgar assembled the Sursum corda by drawing upon material composed years earlier, including the slow movement of an unfinished violin sonata from 1887. This stirring score, whose Latin title is drawn from the Roman Catholic liturgy and translates as "Lift Up Your Hearts," reflects Elgar's growing fascination with Wagner. Robert Anderson has noted that the climax of the middle section "recalls the solemnity of Titurel's exequies in Parsifal." (After the Sursum corda, Elgar supplied music for many royal occasions, especially after the massive success of the Pomp and Circumstance March No. 1 in 1901.)

A highly proficient violinist — he once performed a cycle of the complete Beethoven violin sonatas — Elgar was well aware of the lucrative market for short "salon" pieces for violin and piano. He composed a number of such works, including the famous Salut d'amour, Op. 12 (originally titled Liebesgruss), written in July 1888 as a gift for his fiancée, Alice Roberts. (Unfortunately, Elgar sold Salut d'amour outright for a modest sum, and then watched disconsolately as it generated a fortune in royalties for the lucky publisher.) Other violin pieces, which, like Salut d'amour, Elgar himself arranged for small orchestra, include the gently nostalgic Chanson de nuit, Op. 15, No. 1, and Chanson de matin, Op. 15, No. 2 (both published and orchestrated in 1899). Like these pieces, the effervescent Sevillana, Op. 7 (1884) for small orchestra is an elegant example of the music that Elgar, a populist composer if there ever was one, aimed squarely at a wide public. As William W. Austin writes, "Some admirer's of [Elgar's] symphonies apologize for these light pieces as potboilers, but they need no apology. . . . Their neat, unpretentious forms fit their gentle personal twisting of the common style."

Written for the then vast audience of amateur singers, Elgar's unaccompanied partsongs represent some of his most engaging music. This genre was enormously popular in Britain from the Victorian era through World War II; almost every English composer wrote them, including Elgar's contemporaries Hubert Parry and Charles Villiers Stanford. Elgar's partsongs often concisely express intense emotion, as in "Go, Song of Mine," Op. 57, a setting of a poem by Guido Cavalcanti translated by Dante Gabriel Rosetti. In contrast to the despairing Romanticism of the Cavalcanti partsong, "Owls," Op. 53, No. 4, with a text written by Elgar himself, articulates a nihilism that is no less disturbing for being expressed ironically. "O Wild West Wind," Op. 53, No. 3, makes exhilarating use of stanzas selected from Shelley's famous ode. One of Elgar's most successful secular choral works is the Five Partsongs from the Greek Anthology, Op. 45, for male chorus. In this choral cycle, Elgar evinces a mastery of this difficult medium unmatched by any other British composer, unifying the movements through a subtle development of small motifs.

Although raised as a Roman Catholic, Elgar regularly composed music for the Anglican Church; John Butt has gone so far as to call the composer an "Anglican manqué." The finest of Elgar's Anglican anthems is Give Unto the Lord, Op. 74, a refulgent setting of Psalm 29 composed during the early months of 1914, and showing Elgar's choral technique at its pinnacle. Of Give Unto the Lord, Butt has opined that "there is no other liturgical piece in which Elgar so managed to reconcile his late Romantic desire for thematic transformation coupled with dramatic contrast and balanced form, with the demands of the text and the functions of the piece within the liturgy."

The Piano Quintet, Op. 84, is part of a remarkable trilogy of chamber music masterpieces that Elgar composed in rapid succession as World War I was drawing to a close. Like the Violin Sonata, Op. 82, and the String Quartet, Op. 83, works that comprise the other two panels of this triptych and that will be presented at later concerts of the Bard Music Festival, the Piano Quintet was composed mostly at Brinkwells, a thatched-roof cottage deep in the Sussex countryside. Brinkwells and its environs were so quiet that Elgar and his wife could hear the faint echoes of cannon fire wafting from France during the decisive battles that ended the war. On January 7, 1919, Elgar wrote to the critic Ernest Newman, to whom he dedicated the score, "Your Quintet remains to be completed — the first movement is ready & I want you to hear it — it is strange music I think & I like it — but — it's ghostly stuff." Alice Elgar noted in her diary that the "wonderfully weird"beginning of the quintet possessed the "same atmosphere of 'Owls.'" Jerrold Northrop Moore has associated the first movement's opening measures with both the "Judgment motif" that begins Elgar's oratorio The Dream of Gerontius (1900) as well as the Salve Regina plainchant; other commentators have discerned in this opening the wraith of the famous Dies Irae chant.

After the fevered alternation of nervous outbursts with eerie quietude that characterize the first movement, the calm of the Adagio's opening measures comes as a balm. In a letter to Elgar, George Bernard Shaw described it as a "fine slow movement"and asserted that "nobody else has really done it since Beethoven."The climax of the Adagio is anything but serene, however, recalling the despairing agitation of the opening movement. The finale starts with the chromatic motifs with which the quintet began; these introductory measures are succeeded by an Allegro whose first theme is marked con dignit�. In the course of the Quintet's final movement, this expansive theme is jostled by revenants of the first movement as well as by swinging tunes that mingle reminiscences of Elgar's early salon pieces with echoes from the music hall. Even the triumphant coda cannot wholly dispel the memory of the Mahlerian phantasmagoria that has preceded it.

Bibliography

Elgar and His World. Program for the Bard Music Festival. Anandale-on-Hudson: Bard College, 2007; pp. 14-17.

Last modified 20 November 2012